INTRODUCTION

As the previous modules have demonstrated, it's inevitable that anticoagulation pharmacists will see patients who present management conundrums. Sometimes, the patient is a heavy consumer of alcohol or has actual alcohol use disorder (AUD). Other times, the patient may be pregnant or have antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. In each of these cases, the clinical team needs to pay careful attention. This section of the Anticoagulation Certificate Program is designed to help anticoagulation pharmacists develop the skills necessary to deal successfully with patients who need anticoagulation but have conditions that complicate selection of appropriate anticoagulation. Using case studies, we will navigate some of the more prevalent challenges.

CASE #1: ALCOHOL USE DISORDER

Jean Thomas is a 67-year-old male recently diagnosed with atrial fibrillation (AFib). He currently takes several medications: lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, doxazosin, and diltiazem. He has a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, obesity, prediabetes, and alcohol use disorder (AUD). The anticoagulation clinic has seen Jean for six weeks with occasional international normalized ratio (INR) levels above 3 necessitating multiple changes to his warfarin dose. The SIDEBAR provides some information about assessing patients’ alcohol intake.1

SIDEBAR: Is patient-reported alcohol intake consistent with the amount they actually drink?2

Studies have found that physicians often mentally double patients’ reported alcohol consumption to obtain a more accurate estimate. Evidence suggests that self-reports are often underestimates of alcohol intake. Patient reasoning for this includes that they

- Do not keep track of how much they drink

- Are worried about the doctor judging them

- Don’t want their health problems attributed to alcohol

Evidence indicates that the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) is a suitable screening tool for most community-dwelling individuals. Clinicians can access this tool here: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/coe/cih-visn2/Documents/Provider_Education_Handouts/AUDIT-C_Version_3.pdf.

Indirect non-specific biomarkers can be useful in validating patient alcohol intake. An example of a short-term biomarker is ethanol in breath or urine, which indicates recent alcohol use. Long-term biomarkers include elevated mean corpuscular volume, gamma-glutamyl transferase (downregulated with chronic alcohol use), and the hepatic markers aspartate aminotransferase and alanine transaminase.

While tests evaluating these biomarkers can portray a patient’s alcohol consumption, establishing trust in patient-provider relationships is critical in making the most accurate clinical assessments. A PRO TIP is to approach patients non-judgmentally and non-confrontationally.

PAUSE AND PONDER: Which is TRUE regarding anticoagulants and alcohol use?

- Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is a labeled contraindication to warfarin

- Warfarin’s interaction with alcohol has been well studied

- The team should discuss alcohol use openly with patients

An important aspect of developing a treatment plan based on a patient’s alcohol consumption is providing open, non-judgmental counseling. The clinical team, including prescribers and pharmacists, should discuss alcohol use openly with all patients to form an optimal treatment plan. Clinicians should acknowledge that their patients may drink regularly or have AUD because alcohol consumption is considered a risk factor for the development of AFib.3

Although many clinicians believe warfarin’s labeling lists alcoholism specifically as a contraindication to its use, it does not.4 This misconception may contribute to undertreatment or improper treatment of AFib in patients who use alcohol. A study found that rates of oral anticoagulant therapy (including warfarin) initiation were lower in patients with AUD.5

The potential interactions between warfarin and alcohol have been poorly studied. It is known that alcohol is not significantly metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes, as many drugs like warfarin are. Alcohol is primarily metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase and to a much lesser extent by CYP2E1, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4.6 However, many additional compounds found in alcohol, like hops, flavonoids, and flavor additives, may affect warfarin’s pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics.

Some of the literature sources and guidelines note the possibility of alcohol’s effects such as an increased INR.7 Although there are not many available sources on the subject, small-scale studies have noted that8,9

- Drinking wine daily with meals has no effect on therapeutic hypoprothrombinemia.

- Heavy consumption of wine during fasting has no significant effect on one-stage prothrombin activity, levels of warfarin, or hypoprothrombinemia.

Guidelines recommend that patients with AFib should reduce or discontinue alcohol consumption to lessen AFib recurrence and burden.10 Clinicians may treat patients that are hepatically impaired, whether due to their alcohol consumption or not. In these cases, warfarin’s metabolism and synthesis of clotting factors can be impaired.4

Other conditions affecting patients’ liver function complicate their treatment plans. Because AFib is a common diagnosis in those with liver cirrhosis, anticoagulation therapy needs to be carefully considered. Liver cirrhosis is considered a non-modifiable bleeding risk factor in AFib patients.3 A study found that direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are safer than warfarin in patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis, and that DOACs are contraindicated in Child-Pugh class C patients (liver impairment associated with a 45% 1-year survival rate).3 Dosing warfarin in patients with liver cirrhosis is especially difficult because the coagulopathy associated with this disease state commonly causes elevations in INR.3

Heavy alcohol intake is a significant risk factor for GI bleeding, and warfarin may increase that risk. Warfarin’s package insert lists it as contraindicated in patients with bleeding tendencies associated with active ulceration or overt bleeding of the gastrointestinal tract.4

An additional concern clinicians may have is the risk of falls and bleeding in patients who are frequently inebriated. Evidence from literature dispels this concern, demonstrating that the incidence of severe bleeding is not significantly impacted by the occurrence of falls.11 However, it is worth noting that patients treated intensively (INR range of 2.5 to 3.5), bleeding is more likely to occur.11

In summary, for AFib patients taking warfarin, alcohol use itself is not cause for concern. However, alcohol use lends itself to other comorbid conditions that may impact the way that AFib is treated. The clinical team must counsel warfarin patients about healthy lifestyle choices and reducing alcohol intake in the interest of their overall health. If patients communicate with clinicians about their heavy alcohol use or binge drinking, the team can monitor closely and determine the patient’s individual response. The team must also encourage patients to report changes in alcohol intake openly and honestly. When changes occur, increasing monitoring frequency in patients who binge drink frequently is warranted. A PRO TIP is to track each patient’s INR levels over time, noting what has changed in the patient’s alcohol intake or diet to better make informed clinical decisions going forward.

CASE #2: PREGNANCY

It's Friday afternoon and the clinic is about to close. Jules, a 32-year-old female receiving long term warfarin after experiencing a second deep vein thrombosis two years ago, phones to say she just took a pregnancy test and—oops!—she has an unplanned positive. So, what do we do now, and what are we going to do later?

PAUSE AND PONDER: Under what conditions might a prescriber use warfarin in a patient who is pregnant?

- Only during the first trimester, then patients should be switched to a DOAC

- Never, warfarin is absolutely contraindicated in all trimesters of pregnancy

- In women with mechanical heart valves, who are at highest risk of thromboembolism

Let’s start with this, just in case you are thinking that a DOAC is the way to go: clinicians should avoid prescribing oral direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran) and factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban) in patients who are pregnant or lactating. The data concerning their effects on the woman, fetus, and breastfeeding neonate are insufficient to determine safety.12

Warfarin crosses the placenta, and fetal plasma concentrations are similar to maternal concentrations. Since the fetus’s liver enzyme system is immature, the fetus is severely overdosed by these levels.13 Patients who are at highest risk for venous thromboembolism during pregnancy are those with a mechanical heart valve. Subsequently, warfarin is only approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in pregnant women if they have mechanical heart valves, because they are at high risk of thromboembolism.14

The team’s goals for therapy in pregnant women are

- Treat and prevent thrombosis during the pregnancy, as pregnancy itself increases risk of thrombosis.

- If warfarin is used, it must be stopped and changed to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for at least the first trimester of pregnancy. Pregnant women without mechanical heart valves, that still require anticoagulation, should remain on LMWH therapy for the duration of the pregnancy.

- Discontinue anticoagulation rapidly at the time of birth to prevent bleeding events.

Warfarin therapy during the first trimester of pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of prematurity, miscarriage, and stillbirth. Warfarin is a known teratogen. Warfarin therapy also increases risk of congenital abnormalities of the fetus, including nasal hypoplasia, cleft lip/palate, and skeletal abnormalities, among others.15 Mechanical valve thrombosis is prevented more effectively with warfarin compared to unfractionated heparin (UFH) or LMWH in patients with mechanical heart valves. Table 1 summarizes the data. Consequently, after the first trimester, guidelines recommend restarting warfarin therapy in pregnant patients who meet this criteria.16 Exposure to warfarin after the first trimester has been linked to some minor developmental slowing, but babies usually catch up developmentally later in childhood.15

Table 1. Risk of Mechanical Valve Thrombosis by Treatment Regimen17

| Treatment Regimen |

Risk of Mechanical Valve Thrombosis |

| Warfarin only |

2.7% |

| LMWH only |

8.7% |

| Unfractionated Heparin Only |

11.2% |

| Sequential strategy (LMWH in 1st trimester followed by warfarin) |

5.8% |

Clearly, the fact that warfarin is the best agent to prevent mechanical valve thrombosis is complicated by the risk to the fetus when using warfarin in the first trimester. As soon as pregnancy is detected, patients with mechanical heart valves taking warfarin should immediately discontinue warfarin and start LMWH twice daily.18 This transition period carries a high risk of mechanical valve thrombosis. Evidence suggests that the recommended therapeutic dose of enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily is not sufficient to bring patients to the desired peak anti-Xa levels. Patients started on enoxaparin 1 mg/kg had to be rapidly titrated according to peak monitoring parameters, which leads to the recommendation to start LMWH at higher than the therapeutic dose recommendation, shown in Table 2.18

Table 2. Initial Dosing of LMWH in Pregnant Patients with a Mechanical Heart Valves

| Low Molecular Weight Heparin |

Dose |

| Enoxaparin |

2.5 mg/kg/day |

| Dalteparin |

250 units/kg/day |

| Tinzaparin |

25 units/kg/day |

Ultimately, LMWH dosing in patients with mechanical heart valves should be guided by target Anti-Xa levels, as seen in Table 3. Pregnant patients initiated on twice daily LMWH therapy should be frequently monitored for peak Anti-Xa levels; a PRO TIP is to draw levels 3 to 4 hours after dose is taken.

Table 3. Target Anti-Xa Levels for Pregnant Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves18

| Type of Mechanical Heart Valve |

Target Anti-Xa Levels |

| Aortic valve prosthesis |

0.8-1.2 international units/mL |

| Mitral and right-sided valve prosthesis |

1.0-1.2 international units/mL |

Due to ease of dosing and proper administration in the outpatient setting, use of LMWH is recommended over UFH.19 Risk of adverse events is lower and therapeutic response is more predictable with LMWH.20 UFH can be used, but is not recommended. Once patients with mechanical heart valves are outside of the crucial first trimester window (around the 13th week of pregnancy), patients can be transitioned back onto warfarin, with close INR monitoring.18 It is important to note that a patient’s warfarin dosing may not be the same as it was pre-pregnancy due to changes in anticoagulant factors during pregnancy.21 Two weeks before scheduled delivery or 36 weeks of pregnancy at the latest, clinicians should transition patients back onto a heparin-based therapy.18

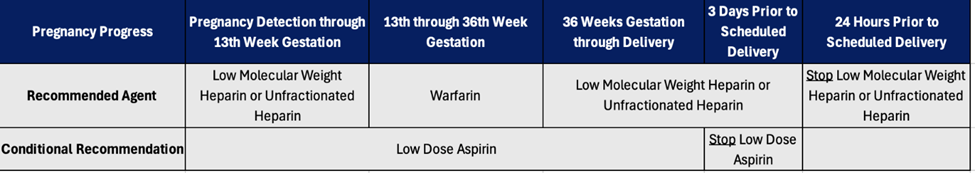

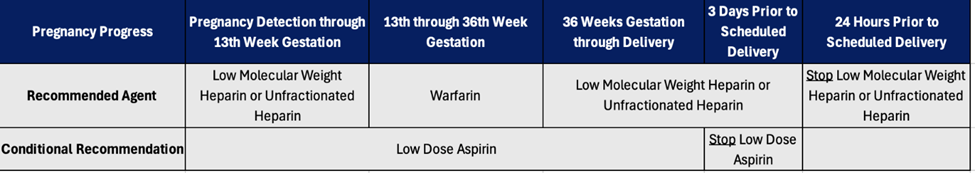

Some evidence suggests that low-dose aspirin therapy, in combination with warfarin therapy, reduces the risk of mechanical valve thrombosis, but carries a higher risk of bleeding. Pregnant patients with mechanical heart valves should be started on low dose aspirin therapy early in pregnancy, so long as aspirin therapy is not contraindicated.18 If aspirin therapy is used, it should be stopped three days prior to planned delivery. Figure 1 summarizes anticoagulation in pregnant patients with mechanical heart valves.

Figure 1. Summary of Anticoagulation in Pregnant Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves

The CHEST guidelines don’t mention AFib in pregnancy, but the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) suggests changing anticoagulation to adjusted dose LMWH in the first trimester (as soon as pregnancy is confirmed). Warfarin has been proven to reduce the risk of stroke in these patients, although clinicians currently use DOACs preferentially. Pregnant patients cannot take DOACs, so warfarin is recommended after the first trimester to prevent stroke in patients with AFib.22 Warfarin can be resumed or initiated after the first trimester up until the last month of pregnancy when patient should be returned to LMWH prior to birth.23,24 This follows the recommendations for anticoagulation in patients with mechanical heart valves.

Patients receiving therapeutic doses of LMWH have an almost 2-fold increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage in instances of spontaneous labor compared to planned induction of labor.19 If the patient goes into labor unexpectedly while still taking warfarin therapy (or within two weeks of last warfarin dose), a cesarean section may be required to reduce fetal bleeding complications from labor.18 The newborn may need to receive vitamin K (IM or IV instead of by mouth, as is the current standard of care) and fresh plasma upon delivery.20 If the patient goes into labor spontaneously within 24 hours of last LMWH or UFH dose, providers can consider protamine after monitoring the PTT and/or anti-Xa levels if the patient is at risk for life threatening hemorrhage.18 Table 4 indicates how protamine can be dosed in the pregnant woman immediately prior to giving birth.25

Table 4. Protamine Dosing after Spontaneous Labor

| Anticoagulant |

Protamine Dose |

| Heparin |

1 mg per 100 unit of heparin |

| Enoxaparin |

1 mg protamine per 1 mg enoxaparin |

| Dalteparin or tinzaparin |

1 mg of protamine per 100 unit of LMWH administered in last 3-5 half lives |

*Maximum single dose of protamine is 50 mg

ABBREVIATION: LMWH = low molecular weight heparin

A key concern prior to delivery is epidural administration of analgesics for the mother, as using injectables while a patient is anticoagulated is risky. For this reason, many obstetricians will schedule and induce labor in anticoagulated patients. The European Society of Anesthesiology currently recommends waiting at least 12 hours after cessation of prophylactic LMWH or at least 24 hours after cessation of greater-than-prophylactic dose LMWH therapy before inserting an epidural catheter.26 To ensure the patient has access to an epidural prior to birth, the team should attempt to discontinue LMWH therapy 24 hours before scheduled induction. In high-risk patients, clinicians can use an UFH infusion while the patient is hospitalized and discontinue it six hours before an induced delivery. If an epidural catheter needs to be placed, there must be a four to six hour interval between the last dose of UFH and epidural placement.26

After birth, anticoagulation is a little easier. If the patient is anticoagulated again after delivery and an epidural is still in place, clinicians must wait a minimum of 12 hours after the last anticoagulant dose before removing the catheter.18 Additionally, clinicians must wait an additional four hours after the epidural catheter is removed before administering LMWH or UFH therapy.26 Patients can be transitioned back onto warfarin five to seven days after delivery.18

Multiple options are available for breastfeeding women who need anticoagulation. UFH molecules are too large to pass into breast milk and warfarin has not been found to pass into breast milk. A PRO TIP is that warfarin dosing may differ in the post-partum period from pre-pregnancy due to differences in anticoagulation factors, so frequent monitoring is required. While LMWH products do pass into the breastmilk, their oral bioavailability is very low and has not been shown to cause fetal harm. However, the CHEST guidelines recommend against using DOACs in breastfeeding women as they cross into the breastmilk and there is not enough data to show degree of fetal harm.19

CASE #3: ANTIPHOSPOHLIPID SYNDROME

Stella is a 42-year-old female with a history of multiple miscarriages and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) after a major motor vehicle accident six weeks ago. Stella has recently been diagnosed with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

PAUSE AND PONDER: A colleague reviewing Stella’s case notices that keeping her INR in range has been difficult and has required a wide variation in weekly warfarin dosing. What does your experienced colleague recommend?

- Continue to adjust her warfarin based on the point-of-care (POC) testing values

- Maintain the same dose for two weeks regardless of the POC testing level

- Try a different monitoring approach

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disease that manifests as a persistent presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLA) coinciding with thrombotic events or pregnancy complications. Table 5 lists a few antiphospholipid antibodies and their abbreviations.27 Classified APS cases must meet at least two criteria – one clinical and one laboratory. The clinical criterion is met through the presence of either pregnancy morbidity or vascular thrombosis. The laboratory criterion is met through high or medium titers of aCL, LA, or aβ2GPI antibodies. Positive titers must be measured at least 12 weeks apart to meet the criterion. In recent years, new antibodies and increased awareness have changed diagnosis and definition of APS, resulting in constantly changing classification criteria.28

Table 5. Antiphospholipid Antibody Abbreviations

| Antiphospholipid Antibody |

Abbreviation |

| lupus anticoagulant antibody |

LA |

| anti-cardiolipin antibody |

aCL |

| anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I IgG & IgM antibody |

aβ2GPI |

The antibodies cause a prothrombotic state, contributing to miscarriages and thrombosis.29 Thrombotic outcomes may be due to aPLA contributions to increased thrombus formation and platelet activation.30 Approximately 80% of APS cases are characterized by thrombosis (venous or arterial) and the remaining 20% of cases are characterized by obstetric complications (such as miscarriages or fetal death). APS is associated with the highest risk of thrombosis in cases of triple positive aPLA or LA, aCL, and aβ2GPI positivity. Cases in which aCL is detected in isolation are associated with the lowest risk. APS generally occurs more often in women than in men, and prevalence increases in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus or venous thromboembolism (VTE).27

The primary treatment for APS is use of anticoagulants.27 However, APS is a rare disease with varying presentations and limited information on diagnosis and classification, resulting in constantly evolving management strategies.31

For primary antithrombotic prophylaxis, or prevention of a first thrombosis, low-dose aspirin (75-100 mg/day) is recommended. Studies show that low-dose aspirin can reduce thrombotic event occurrence 2-fold; however, these are primarily observational studies. For high-risk situations (such as severe injuries or pregnancy), LMWH can be used.27

For patients with APS and a first thrombotic event, warfarin is the preferred anticoagulant treatment. The target INR is 2.0 to 3.0. DOACs are first-line treatment for first thrombotic events in the general population, but in patients with APS they are not recommended due to decreased efficacy compared to warfarin, seen in increased recurring thromboses.32 DOACs can be considered in cases where patients are adherent to warfarin therapy and are unable to achieve INR target range or patients are contraindicated to use warfarin.31 Warfarin is also considered first-line for secondary antithrombotic prophylaxis or prevention of recurrent thrombotic events following a first thrombosis.33

Warfarin is considered embryotoxic, and is contraindicated in pregnancy as discussed in the previous section. Pregnant women with thrombotic APS should switch from warfarin to LMWH before the 6th gestational week and continue therapy until delivery. However, patients with strong indications for warfarin can consider re-initiation in the second and third trimester after embryogenesis.27

As stated above, warfarin is essential in APS treatment. However, APS can interfere with INR measurements, usually elevating them falsely. This may be due to antiphospholipid antibodies reacting with thromboplastin.34 The INR elevation is more prevalent in POC testing, possibly due to the proposed interaction between antiphospholipid antibodies and test reagents (such as commercial thromboplastins). Thus, venipuncture (VP) testing may be preferred as a more accurate measurement of INR in clinical settings to attain therapeutic warfarin dosing.35

However, POC testing has numerous benefits compared to VP testing. In some situations, it is operationally valuable to consider using POC testing, such as for patients on whom it is difficult to perform VP testing,34 or during situations that require global precautions, like the COVID-19 pandemic. Generally, POC testing improves patient convenience and accessibility.35

POC testing, VP testing, and another test—CoaguChek XS—can be performed on the same day to correlate the different test results. CoaguChek measures chromogenic factor X level (cFX). cFX is generally unaffected by APS as it is not phospholipid-dependent, but this test may not be readily available and may require sending specimens to another laboratory. A cFX goal of 20% to 40% correlates with a goal INR of 2.0 to 3.0. Several same-day samples can be collected and correlated to adjust the goal INR matched to the patient’s elevated levels.34 Clinicians might consider POC testing use if the variation between POC tests and VP tests is less than or equal to 0.5 in INR readings. To assess validity of the correlation between paired tests, sampling can be repeated every three to six months.35

As an example, the clinic started a 31-year-old female patient with APS on warfarin with an initial INR goal of 2.0 to 3.0. Table 6 shows repeated test results. Her POC testing INR was adjusted to account for the natural elevation due to APS. After the first correlation point, her POC INR goal was set to 2.5 to 3.0, and after the second correlation point it was increased to 2.5 to 4.0. However, her VP INR remained at 2.0 to 3.0.34

Table 6. Repeated Tests Results for a 31-year-old Woman with Antiphospholipid Syndrome

| Correlation Point |

VP INR |

POCT INR |

cFX |

| 1 |

2.1 |

2.5 |

34% |

| 2 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

-- |

| 3 |

2.8 |

4.1 |

-- |

Anticoagulation pharmacists should note aberrant INR tests, such as values at or above 4.8 and call patients back for additional testing. Additionally, APS may affect different POC devices and different laboratory equipment differently. The clinic will need to re-correlate if it receives new devices or if the lab has to change reagent in their INR machines.35 The correlation process is individualized and cannot be extrapolated between patients.34 Few formal evaluations of the reliability of testing methods exist, highlighting an area which requires more research.

CASE #4: MONITORING FREQUENCY

Shirley is a 68-year-old female with a prosthetic mechanical atrial valve. She has been in the therapeutic INR range with the same dose (no changes) for the past five months; she is remarkably stable.

PAUSE AND PONDER: When reminded to return in four weeks for INR monitoring, she says “Ugh, why do I keep having to come back? Can I come back less often?” How would you respond?

- It’s dangerous to go more than four weeks without testing

- Testing every four weeks is the standard

- Maybe we could have you come in less often

In the United States, common practice is to monitor a patient’s INR for warfarin dose adjustments every four weeks. To compare, in the United Kingdom, anticoagulant prescribers commonly use intervals of up to 90 days.36Although many clinicians feel most comfortable continuing to monitor monthly, returning every four weeks for INR monitoring creates a large burden for anticoagulated patients. Clinicians must empathize with patients and utilize alternatives when it is clinically safe to do so. This may come in the form of extended intervals between INR monitoring or at home POC testing. The 2012 CHEST guideline revision suggested an INR testing frequency of up to 12 weeks with a level of evidence of grade 2B (weak recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) in patients who have demonstrated periods of stable INR control.36

The initial evidence for extended intervals dates back to 2011.37 In a groundbreaking trial, Warfarin Dose Assessment every 4 weeks versus every 12 Weeks in Patients with Stable International Normalized Ratios, researchers enrolled 126 participants in a 4-week follow-up arm and 124 participants in the 12-week follow-up arm. The trial size was fairly small. Eligible participants had to have been enrolled in a clinic and receiving the same maintenance dose for at least six months. The trial was blinded in the sense that all participants had blood drawn every four weeks, but the researchers discarded the 4- and 8-week draws in the extended interval group. The researchers used a surrogate marker, time-in-therapeutic range (TTR) to measure control and quality of therapy. Participants in the 4-week monitoring group (55%) were more likely to have dose adjustments than those in the second group (37%). Groups had similar numbers of subsequent out-of-range next INR values (27.3% in the 4-week arm, 28.4% in the 12-week arm). Major bleeding events were also similar, but rates of clinically relevant non-major bleeding (0.02 per 100 patient-years versus 0.09 per 100 patient-years) and emergency department visits (0.07 per 100 patient-years versus 0.19 per 100 patient-years) were lower for eligible patients with extended INR testing intervals than for those with shorter INR testing intervals.37 The researchers concluded that extending the warfarin dosing assessment interval to every 12 weeks is probably safe for patients on stable doses if they continue to have supportive contact at least every four weeks.37

The ACCP recommends monitoring every 12 weeks in patients who are stable, which is indicated by at least three months of consistent results with no required adjustment of vitamin K antagonist dosing. However, instances in which the INR becomes subtherapeutic or supratherapeutic at these every 12 week appointments, the clinical team should increase the monitoring frequency until the patient achieves a stable INR again.38

One proposed model adjusts follow-up frequencies based on the appropriateness for each patient. A 2019 single-arm prospective cohort study titrated patients on a stable dose of warfarin up to the 12-week recall interval to assure that appropriate patients had their follow-up times extended. Qualifying patients had achieved their target INR of 2.0 to 3.0 for six months. The follow-up interval was first extended to 5 to 6 weeks, then 7 to 8 weeks, then 11 to 12 weeks, after which the researchers repeated the 11 to 12-week follow-up interval. If patients met an exclusion criterion (such as drug interaction, procedure, or hospitalization) or their INR was out of range, they would return to the usual care follow-up time (four weeks). Only restabilized patients would be re-titrated to the 12-week interval. This study suggests a future controlled trial design for methods of extending a stabilized patient’s INR follow-up interval.39

SIDEBAR: Point-of-Care Testing 40,41

Not all providers feel comfortable switching their patients to 12-week monitoring. Since their patients might be seeking alternatives to returning to the clinic every four weeks, providers should know what other options are available. POC testing offers an alternative to patients who wish to avoid returning to the clinic for INR monitoring and dose adjustment every four weeks. Although the POC testing systems can be quite pricey, the time the patient saves by reducing clinic visits may be worth it.

- Patient Self-Testing (PST): Patients test their own INR at home, data is reported to the clinic remotely, and a clinician adjusts the dose if necessary.

- Reduces patient burden by limiting trips to the anticoagulation clinic, and also limits provider burden

- Studies show that patients who monitored frequently (mostly weekly) had a greater TTR.

- Depends on the individual patient’s health literacy

- Increased convenience can be pricy–a trade off

- Overall - a safe option for patients that meet the criteria, even if it is not the most cost effective

- Patient Self-Monitoring (PSM): Patients test their INR at home and are allowed to adjust their dose in response to the INR based on predetermined protocols.

- Lessens burden on providers who are no longer consistently monitoring a patient’s INR and making adjustments

- Requires extensive patient education

- Success also depends on a patient’s ability to afford and manage these POC devices and calculate dose adjustments

- Has been proven superior to PST in reducing mortality.

- Overall - this might not be the most cost-effective option but is safe

The 2018 American Society of Hematology guideline includes a conditional suggestion for recall intervals no longer than 4 weeks for patients undergoing dose adjustment due to out-of-target-range INR measurements. However, for patients experiencing periods of stable INR control, a longer recall interval is strongly recommended, generally 6 to 12 weeks. Additionally, patient self-testing (PST) - a form of home POC testing - is recommended over other INR testing approaches with the exception of patient self-management (PSM). PSM is a form of POC testing in which the patient tests their INR at home and self-adjusts vitamin K antagonist dosing.41

CONCLUSION

Pharmacists who work in anticoagulation will see patients like those described in this module. A PRO TIP is to think of each patient as an individual, ask questions, and avoid making judgments.