Learning Objectives

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

1. Describe gout's pathogenesis, relationship to hyperuricemia, and complications of untreated gout

2. Describe the diagnosis and goals of therapy for gout

3. Recall nonpharmacologic therapy for the management of gout and medications that can increase serum uric acid level

4. Discuss the appropriate approach to gout therapy (acute attack treatment, prevention of future gout attacks, "medication-in-pocket," and "treat-to-target") and its timing

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to:

1. Describe gout's pathogenesis, relationship to hyperuricemia, and complications of untreated gout

2. Recall nonpharmacologic therapy for the management of gout and medications that can increase serum uric acid level

3. Recognize different pharmacological classes and regimens for urate-lowering therapy (ULT) and target serum uric acid level

4. Define the "treat-to-target" and "medication-in-pocket" approaches in gout therapy

Release Date: January 10, 2024

Expiration Date: January 10, 2027

Course Fee

Pharmacists: $7

Pharmacy Technicians: $4

There is no funding for this CE.

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-24-006-H01-P

Pharmacy Technician: 0009-0000-24-006-H01-T

Session Codes

Pharmacist: 24YC06-JBX39

Pharmacy Technician: 24YC06-XJB44

Accreditation Hours

2.0 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-24-006-H01-P/T will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Samar Nicolas, RPh, PharmD, CPPS

Assistant Professor of Pharmacy Practice

MCPHS University

Worcester/Manchester, MA

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Samar Nicolas has no relationships with ineligible companies.

ABSTRACT

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis affecting about 9.2 million adults in the United States (US) and is the result of hyperurice-mia. Gout results from the chronic deposition and crystallization of urate in the joints and tissues. Although gout can affect any joint, initial attacks usually in-volve the big toe joint. The most recent guideline for the management of gout recommends colchicine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or glucocorticoids (oral, intraarticular, intramuscular) as first-line agents for the treatment of gout flares. Patient-specific factors guide the drug choice among the first-line agents. Interleukin-1 inhibitors or adrenocorticotropic hormone are alternative agents. Pharmacists are well-positioned to assess adherence to ULT and educate patients about the importance of urate lowering therapy. Pharmacy technicians can ensure that patients have refills on their medication-in-pocket prescription to facilitate early initiation.

CONTENT

Content

INTRODUCTION

“I’ve been shot, and I’ve been stabbed; nothing compares to gout pain.”

This is how Jim, a 77 year old man, describes his pain as he hobbles into the pharmacy to refill his prescription for colchicine. Jim complains that colchicine is not controlling his gout. He is wearing slippers that show his red swollen joint around his right big toe that is warm and painful to touch. Jim says his physician explained that these symptoms are due to podagra, uric acid crystallization and settling in the joint between his foot and big toe.1 As Jim speaks, his breath projects a strong alcohol smell.

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis affecting about 9.2 million adults in the United States (US) and is the result of hyperuricemia.2,3 Men are at higher risk of developing gout than women.4 Other risk factors include post-menopause, genetics, end-stage renal disease, and major organ transplant.

Uric acid overproduction, under-excretion, or both, elevate serum uric acid levels.5 Underexcretion of uric acid accounts for about 90% of gout cases.6 Human bodies produce uric acid as they break down dying tissues.4 Other sources of uric acid are foods high in purines, such as meats, seafood, and alcoholic beverages.7, 8 Ancient Greek history states that only rich people, who could afford these expensive foods, experience gout.9 Therefore, in the 5th century before Christmas (B.C.), people referred to gout as “the disease of kings.”10

PATHOGENESIS

Uric acid circulates in the blood as monosodium urate.11 In the kidneys, uric acid and urate undergo filtration and secretion into the filtrate followed by about 90% reabsorption into the blood.12 The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline defines hyperuricemia as serum uric acid of 6.8 mg/dL or greater, the level above which urate becomes insoluble in the blood.4

Gout results from the chronic deposition and crystallization of urate in the joints and tissues.4,13 Insoluble monosodium urate crystals form stone-like deposits, known as tophi, in soft tissues, synovial tissues, or bones.14,15 Tophi trigger an inflammatory response, which presents as an acute gout attack.15,16 However, hyperuricemia does not always result in gout.4

Although gout can affect any joint, initial attacks usually involve the big toe joint. Gout attacks are sudden and very painful.17 Acute gout attacks reach maximum pain level in 12 to 24 hours and may last 3 to 14 days if patients do not seek therapy.18 For this reason, all healthcare providers including those on pharmacy teams need to educate patients to seek medical care. Effective gout management reduces the risk of long-term complications like degenerative arthritis, urate nephropathy, infections, renal stones, joint fractures, and nerve or spinal cord impingement.19

DIAGNOSIS OF GOUT

Clinicians diagnose gout by collecting patient history, examining the patient, laboratory workup, and imaging.19 Uric acid crystals in the synovial fluid or tophi in tissues and/or bones confirm gout diagnosis regardless of the uric acid level.4

TREATMENT OF GOUT

The ACR guideline describes 3 treatment goals for patients with gout20:

- Terminating the acute gout attack

- Preventing future attacks

- Lowering the serum uric acid level

Terminating the Acute Gout Attack

The ACR published the most recent guideline for the management of gout in 2020. The ACR guideline recommends colchicine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or glucocorticoids (oral, intraarticular, intramuscular) as first-line agents for the treatment of gout flares.20 Patient-specific factors guide the drug choice among the first-line agents. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) are alternative agents.20 If a first-line agent is ineffective, intolerable, or contraindicated, the ACR guideline recommends switching to another first-line agent before trying alternative agents. Topical ice is an adjunct to pharmacologic therapy. The severity of the gout flare guides the treatment duration.

Colchicine

Colchicine exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by binding to free tubulin dimers leading to microtubule polymerization inhibition, which affects cellular function.21, 22 Colchine has had an interesting history, as the SIDEBAR explains. Common side effects of colchicine are dose-dependent and include diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Because of its mechanism of action, toxic levels of colchicine inhibit cellular division leading to failure of multiple organs .22 Colchicine doses of 0.8 mg/kg are lethal.23 Colchicine undergoes extensive tissue distribution and therefore, a lower dose can be toxic in patients with liver or renal failure. Some unchanged colchicine undergoes renal excretion through glomerular filtration and therefore, requires dosage adjustment for renal dysfunction.21, 24 Cytochrome P450 3A4 hepatic enzymes metabolize colchicine.21, 25 P-glycoprotein facilitates colchicine removal from the body.26 Co-administration of medications that inhibit CYP3A4 enzyme activity (example: grapefruit juice, azole antifungals, erythromycin, verapamil) increase the risk of colchicine toxicity.21, 25 In addition, co-administration of colchicine with P-glycoprotein inhibitors (example: digoxin) increases the risk of colchicine toxicity.26 Toxic symptoms are dose-dependent with increasing severity.27 Patients with toxicity may present with gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), hypotension, lactic acidosis, or acute kidney injury.22, 27 To decrease the risk of toxicity, colchicine’s prescribing information recommends avoiding its co-administration with P-glycoprotein inhibitors or CYP3A4 inhibitors in patients with renal or hepatic impairment.28 For other patients, the prescribing information recommends weighing risks versus benefits before co-administering colchicine with medications that pose a significant drug interaction.

SIDEBAR: HISTORY OF COLCHICINE

Colchicine is derived from a plant, Colchicum automnale.29 Other names for this plant include Autumn Crocus, meadow saffron, naked lady, and colchicum.30 Ebers Papyrus, an Egyptian medical document on herbs dating back to 1500 BC, indicates the use of C. automnale for joint pain.31 In 1833, a German pharmacist analyzed the substance and gave it the name colchicine.29 In France, in 1819, a chemist and a pharmacist isolated colchicine from the plant. In 1884, a French pharmacist produced and sold colchicine as 1 mg granules, which is still available in some countries.29,32 Colchicine accounts for about 0.1-0.6% of the plant content.33 Non-surprisingly, the C. automnale plant is poisonous. Humans should not ingest the plant. Symptoms of C. automnale toxicity resemble the side effects or toxicity of colchicine.34 These symptoms range from diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting to organ failure and death.

Colchicine was available for decades in the US without a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved labeling.35 Despite the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act requiring the FDA to approve medications based on efficacy and safety data, colchicine was grandfathered in. Grandfathered drugs were medications available on market before the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act of 1938 or its amendments in 1962.

In 2006, the FDA initiated the unapproved drug initiative (UDI).36 The goal of the UDI program was to decrease the number of medications in the United States that do not carry FDA approval. Under the UDI program, the FDA allowed exclusive marketing to manufacturers who obtain FDA approval. Some pharmacists and pharmacy technicians may recall colchicine shortage as manufacturers of colchicine received warning letters from the FDA to stop selling colchicine.37 Mutual Pharmaceutical Company submitted a new drug application (NDA) for colchicine in November 2008.38 The UDI did not require manufacturers to conduct new clinical trials to obtain FDA approval. Mutual Pharmaceutical Company’s NDA included data from randomized controlled trials in 1974 and 2004 that proved the safety and efficacy of colchicine. As a result, in July 2009 the FDA approved colchicine for the treatment of gout and familial Mediterranean fever. Colchicine came back to the US market under brand name Colcrys.39

Colchicine is light sensitive. Pharmacies should protect colchicine from light and dispense it in a light-resistant container.28 The FDA requires pharmacies to distribute a medication guide to patients when dispensing colchicine.40 Medication guides inform patients of potential serious adverse reactions and harm mitigation strategies. The Institute for Safe Medical Practices (ISMP) lists colchicine on the look-alike sound-alike (LASA) list due to potential for confusion with Cortrosyn, which is the brand name for cosyntropin.41 Of note, cosyntropin is a synthetic adrenocorticotropin hormone that has anti-inflammatory properties and is an alternative agent for gout attacks.42 In patients with a history of gout, the ACR guideline recommends a “medication-in-pocket” (discussed below) approach to allow early initiation of an anti-inflammatory drug at the onset of a gout flare.20 Since colchicine has anti-inflammatory properties, it is an option for the “medication-in-pocket” approach.

The pharmacist takes a close look at Jim’s prescription refill history to figure out why colchicine is not working for Jim. The pharmacist explores several possibilities:

- Is Jim adhering to his urate-lowering therapy (ULT)?

- Is Jim refilling his colchicine as part of a gout flare prophylactic therapy upon initiating ULT?

- Is Jim asking for colchicine as a “medication-in-pocket” approach?

- Is Jim consuming excessive alcohol?

- Is Jim eating foods rich in purines?

- Is Jim taking any prescription or over-the-counter medications that may increase his uric acid level?

NSAIDs

The FDA has approved indomethacin, naproxen, and sulindac for the treatment of acute gout flare.43,44, 45 However, the guideline does not recommend a specific NSAID.20 Choice of agent depends on patient-specific factors including cardiovascular (CV) risk, gastrointestinal (GI) risk, cost, and availability without a prescription.46 Celecoxib is a selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor and therefore carries a low GI risk but is associated with a dose-dependent increase in CV risk.47, 48 Ibuprofen carries a low GI risk. Indomethacin, naproxen, diclofenac, and sulindac carry a moderate GI risk.49, 50 Among the nonselective NSAIDs, CV risk is highest with diclofenac and lowest with naproxen.51 Despite differences in CV risk among nonselective NSAIDs, the FDA mandates a boxed warning for all NSAIDs about increased risk of thrombosis, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke.52, 53 In addition, the FDA requires pharmacies to distribute a medication guide to patients when dispensing a prescription for NSAIDs.54 Any NSAID is an option for the “medication-in-pocket” approach.20

Glucocorticoids

The ACR guideline does not recommend a specific oral glucocorticoid.20 Parenteral glucocorticoids (intramuscular, intravenous, or intraarticular) are alternative options for patients who cannot tolerate oral therapy. Glucocorticoids (example: prednisone, methylprednisolone) are an attractive option for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or those who cannot tolerate colchicine or NSAIDs.1,55 Short-term glucocorticoids do not cause significant side effects.56, 57 Glucocorticoids are an additional option for the “medication-in-pocket” approach, including injectable formulations for patients who cannot take oral medications.20 Methylprednisolone is available in different dosage forms such as oral, intramuscular (as acetate or succinate), intravenous (as acetate), and intraarticular (as acetate).58

Anakinra

Anakinra is an IL-1 receptor antagonist.59 It blocks the activity of the inflammatory mediatory IL-1. Anakinra has an off-label indication for gout attacks at a dose of 100 mg subcutaneously daily for 3 to 5 days.60, 61 The ACR guideline classifies anakinra as an alternative agent, particularly due to cost.20 The manufacturer recommends storing anakinra in the refrigerator and protecting from light until ready for administration.62 Patients can self-administer anakinra after demonstrating proper administration technique.59

ACTH

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) binds to melanocortin receptors, which triggers the release of endogenous steroids, thus decreasing inflammation.63 The ACR guideline recommends ACTH as an alternative agent.20,63 ACTH is available as an intramuscular or subcutaneous injection.64 The purified cortrophin formulation carries an indication for acute gouty arthritis.65 The manufacturer does not provide a dosing recommendation specific for gout and recommends caution in patients with renal insufficiency.64-66 The manufacturer recommends storing ACTH in the refrigerator until ready for administration and warming to room temperature before injecting.67

Table 1 summarizes the first-line agents for the treatment of gout flares.

| Table 1. First-line Agents for the Treatment of Gout Flares20, 24, 44-46, 56, 68-71 | |||

| Therapy | Dose | Comment | Monitoring parameters |

| Colchicine | · Day 1 of therapy: Use treatment dose of 1.2 mg by mouth (PO) as soon as possible then 0.6 mg after one hour. Maximum dose 1.8 mg/day.

· Day 2 and until flare resolves, use prophylactic dose of 0.6 mg PO once or twice daily. |

If creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 30 mL/min:

· Use 1.2 mg PO as soon as possible then single dose of 0.6 mg after one hour. Avoid repeating therapy within a 14-day period. · Alternatively, use 0.3 mg PO as soon as possible as a single dose. Avoid repeating therapy within 3-7 days.

If patient is on dialysis: · Use 0.6 mg PO as a single dose. Avoid repeating therapy within a 14-day period. |

Monitor patients with CrCl ≤ 80 mL/min closely for adverse effects. |

| NSAIDs

|

· Indomethacin: 50 mg three time daily until pain is tolerable (usually, 3 to 5 days).

· Sulindac: 200 mg twice daily until attack resolves (usually, 7 days). · Naproxen: 750 mg x 1 dose then 250 mg every 8 hours until attack resolves (usually, 2 days). |

· The manufacturer does not provide recommendations for renal dosage adjustment.

· The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommends avoiding use of NSAIDs If CrCl < 30 mL/minute. |

Monitor GI, renal, and CV toxicity in elderly patients.

Prescribe lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible. |

| Glucocorticoids | · Follow specific glucocorticoid dosing recommendation. | Safest option in patients with CKD. | Monitor serum glucose, blood pressure, electrolytes, mood changes, and recurrent infections. |

Interestingly, a panel consisting of eight patients with gout participated in the development of the 2020 ACR guidelines.20 The patient panel provided valuable input from a patient perspective regarding therapy preference for patients with an established gout diagnosis. The patient panel strongly favored a medication-in-pocket approach for the treatment of acute gout flares. With this approach, the clinician prescribes an anti-inflammatory medication that the patient keeps on hand for use as needed.72 Moreover, the patient panel favored an injectable dosage form for the medication-in-pocket to control the pain faster in patients who can take nothing by mouth. The medication-in-pocket approach ensures that patients have quick access to an anti-inflammatory medication at the first onset of gout attack symptoms.20

Jim’s colchicine regimen is consistent with the “medication-in-pocket” to treat an acute gout flare.

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC GOUT

The goal of chronic gout management is to lower the serum uric acid level with ULT, if indicated, and to prevent future attacks.20 ULT includes medications that decrease uric acid production or promote uric acid excretion.73 The ACR 2020 guideline recommends a “treat-to-target” approach that guides ULT dose titration and maintenance to achieve serum uric acid of less than 6 mg/dL.20 Lower ULT initial dosing with subsequent titration decreases the risk of gout flare associated with ULT initiation.20

Pause and Ponder: What patient factors determine eligibility for urate lowering therapy (ULT)?

Table 2 provides recommendation on initiation of ULT based on patient-specific factors.

| Table 2 - Indication for ULT 20 | ||

| Patient factors | 2020 ACR guideline recommendation | Comment |

| ≥1 subcutaneous tophi | ACR guideline strongly recommends initiating ULT | Moderate or high certainty of evidence that benefits of ULT consistently outweigh the risks |

| Gout-attributable radiographic damage | ||

| ≥2 gout flares per year | ||

| > 1 flare but < 2 flares per year | ACR guideline conditionally recommends initiating ULT | Low certainty of evidence or no data available and/or benefits and risks closely balanced |

| First flare and any of the following:

· Chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage ≥ 3 · Serum uric acid > 9 mg/dL · Urolithiasis |

||

| First gout flare | ACR guideline conditionally recommends against initiating ULT | |

| Asymptomatic hyperuricemia* | ||

*Serum uric acid > 6.8 mg/dL

Pause and Ponder: Which urate-lowering agent is first-line therapy?

Table 3 summarizes urate-lowering medications.

| Table 3 - Urate Lowering Medications 20,74-76 | |||

| Pharmacological class | Mechanism of action | Medication | Comments |

| Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors | Inhibition of xanthine oxidase resulting in decreased conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid. | Allopurinol

Febuxostat |

· Allopurinol is first-line agent.

· Start allopurinol at ≤ 100 mg/day in normal kidney function and ≤ 50 mg/day in CKD stage ≥ 3 then titrate. · Start febuxostat at ≤ 40 mg/day then titrate.

|

| Uricosuric Agents | Inhibition of urate reabsorption in the renal tubules resulting in increased excretion of uric acid in the urine. | Probenecid | · ACR guideline strongly recommends XOI over probenecid for patients with CKD stage ≥ 3

· Start probenecid at 500 mg PO once or twice daily then titrate. |

| Urate Oxidase Enzyme | Catalysis of uric acid oxidation to water-soluble allantoin resulting in increased excretion of the allantoin in the urine. | Pegloticase | · ACR guideline strongly recommends against use of pegloticase as a first-line agent

· Administer pegloticase 8 mg IV infusion every 2 weeks along with methotrexate 15 mg PO once a week with a folic acid supplement. · Start weekly methotrexate and folic acid supplementation 4 weeks before initiating pegloticase and continue while on pegloticase. |

Clinicians usually determine eligibility for ULT when patients present with an acute gout attack.20 Some experts favor initiating ULT two to four weeks after the resolution of a gout attack.77 One reason for this practice stems from the fear of gout attack worsening with ULT initiation. The other reason is the perception that during a gout attack, patients are in too much pain to process information regarding chronic therapy. However, the ACR guideline favors initiating ULT during a gout flare as patients may not return for a follow-up visit to initiate ULT after the flare resolves.20

XANTHINE OXIDASE INHIBITORS (XOIs)

XOI include allopurinol and febuxostat.20 XOI are first-line among urate-lowering agents, and the guideline recommends allopurinol as a first-line agent for all patients with gout, unless contraindicated.

Allopurinol

Allopurinol is associated with an increased risk of allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS), a rare but severe, and potentially life-threatening adverse reaction.78 AHS presents as fever, severe rash, eosinophilia, hepatitis, and acute kidney injury.79 AHS is more common in patients who are African Americans or of Southeast Asian descent.78 Pharmacogenetic studies show that these patients have a gene on their human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system that increases the risk of developing AHS. This gene is the HLA-B*5801 allele.80 The interaction of allopurinol with the HLA-B*5801 allele triggers an immune reaction characterized by T-cell activation.81 Not all patients who are positive for HLA-B*5801 allele develop AHS.82 Risk of AHS increases in HLA-B*5801 allele positive patients who have elevated allopurinol serum level due to dose increase or renal dysfunction.81

In the US, testing for HLA-B*5801 in Caucasians or Hispanics is not cost-effective.83 The 2020 ACR guideline recommends genetic testing for the HLA-B*5801 allele before starting allopurinol for patients who are African Americans or of Southeast Asian descent.20 The guideline recommends starting allopurinol at a low dose of 100 mg daily for normal renal function and a lower dose in case of renal dysfunction.

The prescribing information recommends protecting allopurinol from light.74 ISMP lists the brand name of allopurinol, Zyloprim, on the look-alike sound-alike (LASA) list due to potential for confusion with zolpidem.42

SIDEBAR: DID YOU KNOW THAT THE DISCOVERY OF ALLOPURINOL LED TO A NOBEL PRIZE AWARD?

Gertrude Elion, who earned a master’s degree in chemistry from New York University in 1941, worked as a lab assistant for George Hitchings. Up until the 1950s, scientists produced medications by screening and modifying naturally existing substances.84 However, Elion and Hitchings’ contribution to medicine was groundbreaking to drug development as they introduced drug therapy that was targeted to specific cells. In 1963, Elion and Hutchings discovered that allopurinol blocked the synthesis of uric acid. In 1988, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Gertrude Elion and George Hitchings the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of allopurinol and other medications.85

Febuxostat

Febuxostat carries a boxed warning for increased risk of CV death in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), when compared to allopurinol.86 Therefore, the 2020 ACR guideline recommends selecting another ULT medication in patients with established CVD.20 For patients who experience a CV event while on febuxostat, the ACR guideline recommends switching to a different ULT medication.20 The FDA requires pharmacies to distribute a medication guide when dispensing febuxostat to patients.86

URICOSURICS

Probenecid

Probenecid is the only uricosuric drug approved in the United States.87,88 Probenecid may cause nephrolithiasis (uric acid stones in the kidneys).89 These uric acid stones form as the uric acid crystallizes in an acidic urine. The prescribing information for probenecid recommends adequate hydration and adjunct urine alkalinizing agents (example: sodium bicarbonate or potassium citrate).89 However, the 2020 ACR guideline determined insufficient evidence to recommend the routine use of alkalinizing agents with probenecid.20 Probenecid is usually an add-on therapy in patients with partial response to an XOI. Remember to counsel patients on adequate hydration to decrease the risk of nephrolithiasis.

ISMP lists probenecid on the LASA list due to potential for confusion with Procanbid, the brand name for procainamide, an antiarrhythmic drug.42 Probenecid also has some interesting abuse potential (see the SIDEBAR).

SIDEBAR: CAN PROBENECID HELP ATHLETES IMPROVE PERFORMANCE?

Random drug testing in sports led athletes to misuse probenecid to mask the unlawful use of performance-enhancing drugs such as anabolic-androgenic steroids.90 Probenecid inhibits the tubular secretion of anabolic-androgenic steroids in the kidneys, thus inhibiting their excretion in the urine. As a result, urine drug testing will not detect the use of these illegal substance, and athletes can pass the random drug testing successfully. In 1986, a doping control officer traveled from Norway and collected 6 urine samples from 6 Norwegian athletes who were training in the US. The athletes showed up at least 1.5 hours late probably to allow time for onset of action of the masking agent. Five of the samples showed an unusually dilute urine with low specific gravity. In addition, the concentration of endogenous androgenic-anabolic steroids in the urine samples was at least 100 times below normal.90 These unusual findings along with suspicious behaviors projected by the athletes during the testing process, triggered further analysis of the urine samples. The lab identified a “new masking agent”, probenecid and its metabolite, in these urine samples. Today, probenecid appears on the World Anti Doping Agency (WADA) prohibited list.91 The WADA list serves as a standard for identifying substances that athletes may illegally use to enhance performance in sports.91

URATE OXIDASE ENZYME

Pegloticase

The FDA approved pegloticase for adults with chronic gout refractory to conventional therapy.92 The 2020 ACR guidelines recommends switching to pegloticase when XOIs, probenecid, and other interventions fail.20 In clinical trials, administering methotrexate with pegloticase increased the chance of tophi resolution by 22.8% compared to pegloticase monotherapy.76 Therefore, pegloticase’s prescribing information recommends co-administration with methotrexate, unless contraindicated. Folic acid supplementation decreases the risk of hepatotoxicity and GI side effects associated with methotrexate.93 Pharmacists should counsel patients about the importance of adherence to folic acid while on methotrexate.

The manufacturer recommends storing pegloticase in the refrigerator and protecting it from light before dispensing.76 After diluting pegloticase for IV infusion in an institutional setting, healthcare workers should protect the solution from light.

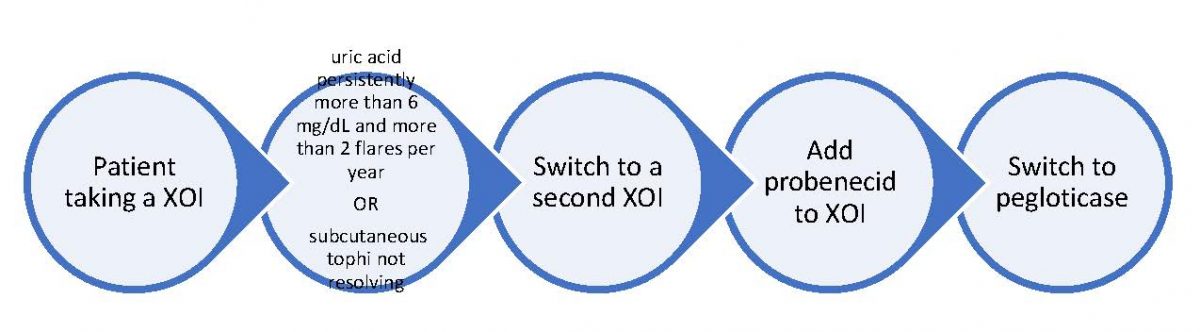

Pause and Ponder: When does the guideline recommend switching urate-lowering agents?

The 2020 ACR guideline recommends using the maximum tolerated or recommended dose of a ULT.20 Figure 1 outlines the management of patients taking a XOI requiring adjustment to therapy:

Figure 1. Switching ULT

Jim’s medication profile reveals that he has been taking allopurinol for little over a year now.

DURATION OF THERAPY

For patients tolerating ULT, the 2020 ACR guideline recommends indefinite therapy to avoid worsening gout and its associated complications.20 Patients may not adhere to therapy due to cost, pill burden, and low health literacy.94 Remember to counsel patient on adherence and goals of ULT as patients may think they do not need to take ULT if they have no symptoms.

PREVENTING GOUT FLARE UPON INITIATION OF ULT

Initiation of ULT may trigger a gout flare due to activation of crystals precipitated in joints.95, 96 The risk of gout flare increases with higher reduction in serum uric acid levels. Studies suggest that gout attacks associated with ULT may decrease patient adherence to ULT.97 Prophylaxis with anti-inflammatory medications decreases the risk of gout flare upon ULT initiation. The 2020 ACR guideline recommends prophylactic therapy upon initiating ULT and for at least three to six months. Patients who continue to experience flares may require a longer duration of prophylactic therapy.20 Experts recommend colchicine or NSAIDs as first-line prophylactic therapy.98 Table 4 summarizes prophylactic medications and recommendations.

| Table 4 – Medications that Prevent Gout Attack with ULT Initiation | |

| Medication | Recommendation |

| Low-dose colchicine | Use 0.6 mg once or twice daily |

| Low-dose NSAIDs | Use naproxen 250 mg or equivalent dose of different NSAID

Add proton pump inhibitor if indicated |

| Low-dose prednisone or prednisolone | Use less than or equal to 10 mg per day

Reserve corticosteroids for patients who cannot tolerate colchicine and NSAIDs |

NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY AND LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS

Serum uric acid levels decrease only slightly with dietary modifications.20 In addition, certain diets may trigger a gout flare. To decrease the risk of flares, the 2020 ACR guideline conditionally recommends the following approaches:

- Limiting alcohol intake

- Limiting purine intake. Some examples of high-purine foods include seafood like sardines, tuna, haddock, and meats like bacon, turkey, veal, and liver.99, 100

- Limiting high-fructose corn syrup intake

- Following a weight loss program if the patient is overweight or obese

Jim projected an alcohol breath when speaking. Jim may be consuming excessive amounts of alcohol. He may be consuming a non-gout friendly diet.

DIGITAL HEALTH AND GOUT MANAGEMENT

Digitalization of health care is rapidly evolving and involves the use of technology to manage health conditions, ameliorate modifiable risk factors, and promote health and wellness.101 Wearable devices such as fitness trackers, patient portals, and mobile apps are only few examples of digital health tools. Investigators suggest that gout mobile health apps may improve patient perception of the disease, clarify beliefs, and benefit self-care.102 However, further studies are essential to prove these mobile applications beneficial. As of this writing, several gout-related mobile health applications are available. Target users for these applications can be clinicians or patients. For example, a physician developed a mobile application called Gout Diagnosis. The application includes an evidence-based algorithm to facilitate an accurate diagnosis of gout.103 On the other hand, patients can download from a variety of existing gout mobile applications at little or no cost.104 The National Kidney Foundation developed a mobile application called Gout Central. This application comes from a reputable foundation and provides patient education on symptoms and risk factors for gout, nonpharmacologic recommendations such as diet and lifestyle modifications, and medications to treat gout and prevent flares.104 The FDA does not regulate mobile medical applications.105 Therefore, the choice of mobile health application depends on patient preference such as cost, ease of use, compatibility, security, and type of content.106

A mobile application may help Jim learn about foods and drinks that may trigger gout attacks.

PHARMACY TEAM IMPACT ON GOUT MANAGEMENT

Pharmacists are the most accessible healthcare professionals. Patients with a gout flare may seek pharmacists for recommendations on pain management. When patients without a previous gout diagnosis present to the pharmacy, pharmacists may recognize signs of gout and refer them to their primary care clinician. Pharmacists can educate patients who have a diagnosis for gout about the phases and goals of gout therapy, including the likelihood that ULT will be a lifelong therapy.

Pharmacists are well-positioned to assess adherence to ULT and educate patients about the importance of ULT.107 Pharmacists can assess patient understanding of various therapies and remind them that anti-inflammatory medications treat acute gout attack or prevent gout flare upon initiating ULT. Pharmacists should empower patients to request from their clinician a medication-in-pocket prescription. Pharmacists should counsel patients on the proper use of medication-in-pocket by reminding them to take the anti-inflammatory medication as soon as possible, ideally within 12 hours of onset of a gout attack.108 In addition, patients may need a reminder about continuing their ULT while taking the medication-in-pocket for acute flares.109

Pharmacy technicians can ensure that patients have refills on their medication-in-pocket prescription to facilitate early initiation. Updating the patient’s records in the pharmacy software with the gout diagnosis can facilitate this continuity of care. The pharmacy team should encourage patients to fill all their prescriptions at the same pharmacy. Through access to all the patient’s medications, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can play a crucial role in optimizing gout management by identifying medications that increase serum uric acid levels.110

In addition, the pharmacy team can identify potential drug-drug interactions. This is particularly important with colchicine as it is a substrate for CYP3A4 and P-gp and has a narrow therapeutic window.111 In addition, some medications are known to increase serum uric acid levels.20 Advising patients to check with the pharmacy team before purchasing an over-the-counter (OTC) medication can decrease the use of inappropriate medications. When completing transactions at the register, pharmacy technicians are well positioned to identify OTC products that can worsen gout, such as vitamin A or niacin.112 On the other hand, frequent purchase of OTC anti-inflammatory medications like naproxen or ibuprofen may imply uncontrolled gout.

Patients can find educational videos on YouTube to learn more about gout therapy and appropriate diet.113 Additional resources are available to patients on goutalliance.org. These include videos, podcasts, guides, and awareness events.114 Some patients may like to learn about their condition using gout-related mobile applications.

Pharmacy interns may benefit in hearing from patients about their experience with gout, especially the debilitating pain. This may help future pharmacists empathize and develop better relationships with patients, which can improve patient outcomes.115

The entire pharmacy team could engage in alleviating misconceptions about gout. Some patients with gout have reported stigma regarding their condition from friends, family members, and healthcare workers.116 Some patients with gout have even reported an internalized stigma. Stigmatization may be due to the misbelief that gout is benign, preventable, or self-inflicted.

Did you know that May 22 is National Gout Awareness Day?

Jim states that he feels embarrassed about wearing slippers that expose his swollen toe. The pain is so intense that he is unable to tolerate a close-toe shoe.

Table 5 summarizes some medications that may increase serum uric acid level.

| Table 5 – Managing Medications that Increase Serum Uric Acid Level and Risk of Gout Attack20,110,117-119 | ||

| Medication | Mechanism | Recommendation |

| Loop and thiazide diuretics

Use: hypertension, edema

|

Decrease urate excretion | The guideline recommends switching to a different antihypertensive and suggests losartan when feasible.

|

| Aspirin (low-dose, 81 mg)

Use: prevention of CVD |

Increases uric acid renal reabsorption and decreases secretion | The guideline conditionally recommends against discontinuing low-dose aspirin with appropriate indication. |

| Niacin

Use: dietary supplement |

Inhibits the enzyme uricase, thus inhibiting the oxidation of uric acid, or decreases uric acid excretion | The guideline does not provide a specific recommendation for niacin-induced hyperuricemia. Experts recommend adequate hydration. |

After looking into Jim’s medication profile and inquiring about his OTC products, the pharmacist does not identify any medication that may be increasing his serum uric acid level.

CONCLUSION

Gout is the most common type of inflammatory arthritis. Untreated gout can lead to complications such as degenerative arthritis, urate nephropathy, infections, renal stones, joint fractures, and nerve or spinal cord impingement. ULT is indicated for chronic gout management. Allopurinol is the first-line urate-lowering agent. Colchicine, NSAIDs, and corticosteroids are indicated for acute flares, and, in lower doses, for gout flare prophylaxis upon initiating ULT. Diet and lifestyle modifications complement the pharmacologic therapy. The pharmacy team plays a crucial role in identifying drug-induced hyperuricemia and educating patients about the importance of adherence to ULT. Gout flares are painful and debilitating. Pharmacists can recommend initiation of anti-inflammatory therapy for acute gout flares. Pharmacy technicians can ensure patients have refills for their anti-inflammatory medication to facilitate the medication-in-pocket approach.

Jim’s uncontrolled gout may be due to various reasons that pharmacy team can investigate. Inquiring about Jim’s drinking habits and educating him about the negative impact of alcohol on gout management is a necessary first step in his therapy. If an adequate trial of dietary changes does not control his symptoms, then switching to a different XOI or adding probenecid, depending on what he has tried so far, would be appropriate.

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

Treating Gout without Doubt

Pharmacist POST-TEST

1. Which of the following patient factors accounts for about 90% of gout cases?

a) Overproduction of uric acid

b) Underexcretion of uric acid

c) Liver dysfunction

2. Why does the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) define hyperuricemia as serum uric acid level greater than or equal to 6.8 mg/dL?

a) All patients with serum uric acid level ≥ 6.8 mg/dL experience gout

b) Serum uric acid level ≥ 6.8 mg/dL is insoluble in the blood

c) Patients with serum uric acid level ≥ 6.8 mg/dL experience urate kidney stones

3. Which of the following is involved in the pathogenesis of gout?

a) Chronic deposition and crystallization of urate in the joints and tissues

b) Chronic deposition and crystallization of calcium in the joints and tissues

c) Increased glomerular filtration rate of uric acid due to caffeine intake

4. Which of the following is a complication of untreated gout?

a) Renal stones

b) Congestive heart failure

c) Visual changes

5. Which of the following findings confirms a diagnosis of gout?

a) Elevated uric acid

b) Tophi in tissues and/or bones

c) Burning upon urination

6. According to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline, which one of the following is a goal of chronic gout therapy?

a) Limiting gout attacks to a maximum of 2 attacks per year

b) Preventing future gout attacks

c) Decreasing the renal excretion of uric acid

7. A 55 year-old-man presents with his first acute gout attack. In the absence of contraindications, which of the following medications is an appropriate first-line therapy for this patient?

a) Colchicine

b) Intramuscular methylprednisolone

c) Anakinra

8. Which one of the following statements is accurate about colchicine drug interactions?

a) Co-administration of colchicine with P-glycoprotein inhibitors increases the risk of colchicine toxicity

b) Co-administration of colchicine with P-glycoprotein inhibitors decreases colchicine efficacy

c) Co-administration of colchicine with CYP 450 3A4 inhibitors decreases colchicine efficacy

9. In the absence of contraindications, which one of the following medications is the first-line urate-lowering therapy?

a) Allopurinol

b) Febuxostat

c) Probenecid

10. A patient presents to fill his first prescription for allopurinol. Which one of the following is an appropriate counseling point for this patient?

a) Start taking allopurinol today and continue indefinitely

b) Discontinue allopurinol once you achieve uric acid level of < 6 mg/dL

c) Keep allopurinol on hand and start taking at the first sign of a gout attack

11. A patient experiences an acute attack of gout. You review his medication profile. Which of the following medications may be aggravating his gout?

a. atorvastatin

b. niacin

c. losartan

12. Which of the following is an appropriate nonpharmacologic intervention for gout?

a. Increasing intake of purine-containing foods

b. Switching from beer or wine to hard alcohol

c. Applying ice to sore joints if tolerable

Pharmacy Technician Post Test (for viewing only)

Treating Gout without Doubt

Technician POST TEST question

1. According to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), what is the definition of hyperuricemia?

a) uric acid level > 6 mg/dL

b) uric acid level ≥ 6.5 mg/dL

c) uric acid level ≥ 6.8 mg/dL

2. Which of the following statements is accurate about gout attacks?

a) Gout attacks happen only in the big toe joint

b) Gout attacks happen only in the morning

c) Gout attacks happen in any joint

3. When should patients with a first gout attack seek medical care?

a) Only if the pain is unbearable

b) Only if the pain lasts more than 10 days

c) Anytime patients experience their first gout attack

4. A patient calls the pharmacy saying that he is starting to experience a gout attack. The patient asks the pharmacy technician to refill his medication-in-pocket prescription. Which one of the following medications can the patient use for medication-in pocket approach?

a) Allopurinol

b) Naproxen

c) Probenecid

5. A pharmacy technician is refilling a patient’s medication-in pocket prescription for colchicine. The technician notices that after this fill, the prescription has no more refills. The patient’s next appointment is in eight months. What is the best next step?

a) Send a refill request to the clinician’s office

b) Inactivate the prescription

c) Tell the patient to request a prescription during their next visit

6. What is the goal of therapy for a patient taking allopurinol as part of a gout regimen?

a) Achieving a serum uric acid level < 6 mg/dL

b) Terminating an acute gout attack

c) Decreasing the intensity of pain during an acute gout attack

7. Which one of the following nonpharmacologic therapy is beneficial for patients with gout?

a) Decreasing the intake of foods high in purines

b) Increasing alcoholic beverages consumption

c) Decreasing the intake of caffeine

8. A patient visits the pharmacy counter frequently to check-out some OTC products. In the past three months, the patient has purchased the same product four times. Which one of the following OTC products may imply uncontrolled gout?

a) Vitamin C

b) Ibuprofen

c) Dextromethorphan

9. A medication guide should accompany which of the following medications?

a) NSAIDs

b) Allopurinol

c) Probenecid

10. Which one of the following medications Is a urate oxidase enzyme?

a) Pegloticase

b) Colchicine

c) Probenecid

11. A patient experiences an acute attack of gout. You review his medication profile. Which of the following medications may be aggravating his gout?

a. atorvastatin

b. niacin

c. losartan

12. Which of the following is an appropriate nonpharmacologic intervention for gout?

a. Increasing intake of purine-containing foods

b. Switching from beer or wine to hard alcohol

c. Applying ice to sore joints if tolerable

References

Full List of References

References

1. Gout: Disease basics, symptoms and treatment options. Gout Treatment : Medications and Lifestyle Adjustments to Lower Uric Acid. Johns Hopkins Arthritis Center. Published 2016. https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/arthritis-info/gout/gout-treatment/

2. Gout. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated April 28, 2022. Accessed December 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/types/gout.html

3. Chen-Xu M, Yokose C, Rai SK, Pillinger MH, Choi HK. Contemporary Prevalence of Gout and Hyperuricemia in the United States and Decadal Trends: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2016. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(6):991-999. doi:10.1002/art.40807

4. Smith RG. The diagnosis and treatment of gout. Medscape. Published May 1, 2009. Accessed December 25, 2022. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704970_1

5. de Oliveira EP, Burini RC. High plasma uric acid concentration: causes and consequences. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2012;4:12. doi:10.1186/1758-5996-4-12

6. Choi HK, Mount DB, Reginato AM; American College of Physicians; American Physiological Society. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(7):499-516. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-7-200510040-00009

7. Gout diet: what’s allowed, what’s not. Mayo clinic. Updated June 25, 2022. Accessed January 1, 2023. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/gout-diet/art-20048524

8. Gout: Disease of the Kings | The Hand Society. www.assh.org. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://www.assh.org/handcare/blog/gout-disease-of-the-kings

9. Gout: Disease of Kings now a 21st Century Epidemic. News-Medical.net. Published September 28, 2022. Accessed July 13, 2023. https://www.news-medical.net/health/Gout-Disease-of-Kings-now-a-21st-Century-Epidemic.aspx

10. Tang SCW. Gout: A Disease of Kings. Contrib Nephrol. 2018;192:77-81. doi:10.1159/000484281

11. Liebman SE, Taylor JG, Bushinsky DA. Uric acid nephrolithiasis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9(3):251-257. doi:10.1007/s11926-007-0040-z

12. Álvarez-Lario B, Macarrón-Vicente J. Uric acid and evolution. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(11):2010-2015. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keq204

13. Mikuls TR. Gout. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(20):1877-1887. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp2203385

14. Ragab G, Elshahaly M, Bardin T. Gout: An old disease in new perspective - A review. J Adv Res. 2017;8(5):495-511. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2017.04.008

15. Salama A, Alweis R. Images in clinical medicine: Tophi. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2017;7(2):136-137. doi:10.1080/20009666.2017.1328967

16. Cronstein BN, Terkeltaub R. The inflammatory process of gout and its treatment. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S3. doi:10.1186/ar1908

17. Burns CM, Wortmann RL. Latest evidence on gout management: what the clinician needs to know. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2012;3(6):271-286. doi:10.1177/2040622312462056

18. Engel B, Just J, Bleckwenn M, Weckbecker K. Treatment Options for Gout. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(13):215-222. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2017.0215

19. Rothschild BM, Diamond HS. Gout and Pseudogout. Medscape. Updated January 11, 2023. Accessed January 25, 2023. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/329958-overview#a1

20. FitzGerald JD, Dalbeth N, Mikuls T, et al. 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout [published correction appears in Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020 Aug;72(8):1187] [published correction appears in Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Mar;73(3):458]. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(6):744-760. doi:10.1002/acr.24180

21. Slobodnick A, Shah B, Krasnokutsky S, Pillinger MH. Update on colchicine, 2017. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(suppl_1):i4-i11. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex453

22. Finkelstein Y, Aks SE, Hutson JR, et al. Colchicine poisoning: the dark side of an ancient drug. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010;48(5):407-414. doi:10.3109/15563650.2010.495348

23. Fu M, Zhao J, Li Z, Zhao H, Lu A. Clinical outcomes after colchicine overdose: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(30):e16580. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000016580

24. Colcrys. Prescribing information. AR Scientific, Inc.; 2009. Accessed December 26, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022353lbl.pdf

25. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published 2019. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-interactions-labeling/drug-development-and-drug-interactions-table-substrates-inhibitors-and-inducers

26. Colchicine: Beware of toxicity and interactions. medsafe.govt.nz. https://medsafe.govt.nz/profs/puarticles/colchicine.htm

27. Long N. Colchicine toxicity. Life in the Fast Lane • LITFL. Published March 5, 2019. https://litfl.com/colchicine-toxicity/

28. Colchicine (HIGHLIGHTS of PRESCRIBING INFORMATION). Accessed August 14, 2023. https://content.takeda.com/?contenttype=PI&product=COL&language=ENG&country=GBL&documentnumber=1

29. Karamanou M, Tsoucalas G, Pantos K, Androutsos G. Isolating Colchicine in 19th Century: An Old Drug Revisited. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(6):654-658. doi:10.2174/1381612824666180115105850

30. Autumn Crocus, Colchicum spp. Wisconsin Horticulture. https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/autumn-crocus-colchicum-spp/

31. Dasgeb B, Kornreich D, McGuinn K, Okon L, Brownell I, Sackett DL. Colchicine: an ancient drug with novel applications. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(2):350-356. doi:10.1111/bjd.15896

32. Colchicine, 1 mg tablets. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://arpimed.am/colchicine-1-mg-tablets/

33. Danel VC, Wiart JF, Hardy GA, Vincent FH, Houdret NM. Self-poisoning with Colchicum autumnale L. flowers. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 2001;39(4):409-411. doi:10.1081/clt-100105163

34. Brvar M, Ploj T, Kozelj G, Mozina M, Noc M, Bunc M. Case report: fatal poisoning with Colchicum autumnale. Crit Care. 2004;8(1):R56-R59. doi:10.1186/cc2427

35. Guglielmo BJ. The Colchicine Debacle. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2013;173(3):184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1405

36. Gunter SJ, Kesselheim AS, Rome BN. Market Exclusivity and Changes in Competition and Prices Associated With the US Food and Drug Administration Unapproved Drug Initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(8):1124-1126. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.1989

37. Gout Disease Control Suffered After FDA-Driven Price Hike: Study. BioSpace. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.biospace.com/article/gout-drug-colchicine-spikes-for-a-decade-after-2010-fda-policy-change/

38. The Unapproved-Drugs Initiative Is Coming to an End. The Rheumatologist. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.the-rheumatologist.org/article/the-unapproved-drugs-initiative-is-coming-to-an-end/

39. Generic Colcrys Availability. Drugs.com. Updated September 6, 2023. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.drugs.com/availability/generic-colcrys.html

40. Research C for DE and. Patient Labeling Resources. FDA. Published online July 24, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/fdas-labeling-resources-human-prescription-drugs/patient-labeling-resources#medication-guides

41. List of Confused Drug Names | Institute For Safe Medication Practices. www.ismp.org. Published February 16, 2015. https://www.ismp.org/recommendations/confused-drug-names-list?check_logged_in=1

42. Cosyntropin - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. www.sciencedirect.com. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/veterinary-science-and-veterinary-medicine/cosyntropin

43. Indomethacin. Prescribing information. Qualitest Pharmaceuticals; 2016. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/018829s022lbl.pdf

44. Naproxen. Prescribing information. Roche Pharmaceuticals; 2007. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/017581s108,18164s58,18965s16,20067s14lbl.pdf

45. Clinoril. Prescribing information. Merck & Co., Inc.; 2010. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/017911s074lbl.pdf

46. Laubscher T, Dumont Z, Regier L, Jensen B. Taking the stress out of managing gout. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(12):1209-1212

47. Celebrex. Prescribing information. Pfizer; 2008. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/020998s027lbl.pdf

48. Solomon SD, Pfeffer MA, McMurray JJ, et al. Effect of celecoxib on cardiovascular events and blood pressure in two trials for the prevention of colorectal adenomas. Circulation. 2006;114(10):1028-1035. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.636746.

49. Henry D, Lim LL, Garcia Rodriguez LA, et al. Variability in risk of gastrointestinal complications with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: results of a collaborative meta-analysis. BMJ. 1996;312(7046):1563-1566. doi:10.1136/bmj.312.7046.1563

50. Safety Comparison of NSAIDs. pharmacist.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed February 6, 2023. https://pharmacist.therapeuticresearch.com/Content/Segments/PRL/2017/Jan/Safety-Comparison-of-NSAIDs-10556

51. McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of the observational studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2. JAMA. 2006;296(13):1633-1644. doi:10.1001/jama.296.13.jrv60011

52. Antman EM, Bennett JS, Daugherty A, et al. Use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: an update for clinicians: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1634-1642. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.181424

53. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Analysis and recommendations for agency action regarding nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and cardiovascular risk. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2005;19(4):83-97.

54. Medication Guide for Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) (See the End of This Medication Guide for a List of Prescription NSAID Medicines.). https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/018766s015MedGuide.pdf

55. Cronstein BN, Sunkureddi P. Mechanistic aspects of inflammation and clinical management of inflammation in acute gouty arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19(1):19-29. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e31827d8790

56. Gotzsche PC, Johansen HK. Short-term low-dose corticosteroids vs placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2005(3):CD000189. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000189.pub2

57. Rowe BH, Spooner C, Ducharme FM, Bretzlaff JA, Bota GW. Early emergency department treatment of acute asthma with systemic corticosteroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD002178. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002178

58. Methylprednisolone: Generic, Uses, Side Effects, Dosages, Interactions & Warnings. RxList. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.rxlist.com/methylprednisolone/generic-drug.htm

59. Kineret. Prescribing information. Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB; 2020. Accessed 02/25/2023. https://kineretrxhcp.com/pdf/Full-Prescribing-Information-English.pdf

60. Sharma E, Pedersen B, Terkeltaub R. Patients Prescribed Anakinra for Acute Gout Have Baseline Increased Burden of Hyperuricemia, Tophi, and Comorbidities, and Ultimate All-Cause Mortality. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;12:1179544119890853. doi:10.1177/1179544119890853

61. Ghosh P, Cho M, Rawat G, Simkin PA, Gardner GC. Treatment of acute gouty arthritis in complex hospitalized patients with anakinra. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(8):1381-1384. doi:10.1002/acr.21989

62. HIGHLIGHTS of PRESCRIBING INFORMATION. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/103950s5136lbl.pdf

63. Daoussis, D., Bogdanos, D.P., Dimitroulas, T. et al. Adrenocorticotropic hormone: an effective “natural” biologic therapy for acute gout? Rheumatol Int 40, 1941–1947 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04659-5

64. Acthar. Prescribing information. Questcor Pharmaceuticals; 2010. Accessed February 26, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022432s000lbl.pdf

65. PURIFIED CORTROPHIN® GEL (Repository Corticotropin Injection USP) Rx only. dailymed.nlm.nih.gov. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=f27544ee-a0e2-4d84-b193-1c9efdf9e34c&type=display

66. Vargas-Santos AB, Neogi T. Management of Gout and Hyperuricemia in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(3):422-439. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.01.055

67. HIGHLIGHTS of PRESCRIBING INFORMATION. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/022432s000lbl.pdf

68. Pisaniello HL, Fisher MC, Farquhar H, et al. Efficacy and safety of gout flare prophylaxis and therapy use in people with chronic kidney disease: a Gout, Hyperuricemia and Crystal-Associated Disease Network (G-CAN)-initiated literature review. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):130. doi:10.1186/s13075-021-02416-y

69. Stevens PE, Levin A; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):825-830. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007

70. Wongrakpanich S, Wongrakpanich A, Melhado K, Rangaswami J. A Comprehensive Review of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use in The Elderly. Aging Dis. 2018;9(1):143-150. doi:10.14336/AD.2017.0306

71. Duru N, van der Goes MC, Jacobs JW, et al. EULAR evidence-based and consensus-based recommendations on the management of medium to high-dose glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1905-1913. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203249

72. Pill in the pocket. Wiktionary. Published October 15, 2021. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/pill_in_the_pocket

73. Stamp LK, Chapman PT. Urate-lowering therapy: current options and future prospects for elderly patients with gout. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(11):777-786. doi:10.1007/s40266-014-0214-0

74. Zyloprim. Prescribing information. Casper Pharma; 2018. Accessed December 25, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/016084s044lbl.pdf

75. Pro-Cid. Prescribing information. Phebra; 2018. Accessed December 26, 2022. https://www.phebra.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Procid-PI-V02.pdf

76. Krystexxa. Prescribing information. Horizon Therapeutics; 2022. Accessed December 26, 2022. https://www.hzndocs.com/KRYSTEXXA-Prescribing-Information.pdf

77. Evidence reviews for timing of urate-lowering therapy in relation to a flare in people with gout: Gout: diagnosis and management: Evidence review F. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2022 Jun. (NICE Guideline, No. 219.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583523/

78. Stamp LK, Barclay ML. How to prevent allopurinol hypersensitivity reactions?. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(suppl_1):i35-i41. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex422

79. Lupton GP, Odom RB. The allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1(4):365-374. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(79)70031-4

80. Delves, PJ. Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) system. Merck Manual. Updated September 2022. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/immunology-allergic-disorders/biology-of-the-immune-system/human-leukocyte-antigen-hla-system

81. Yun J, Adam J, Yerly D, Pichler WJ. Human leukocyte antigens (HLA) associated drug hypersensitivity: consequences of drug binding to HLA. Allergy. 2012;67(11):1338-1346. doi:10.1111/all.12008

82. Jung JW, Kim DK, Park HW, et al. An effective strategy to prevent allopurinol-induced hypersensitivity by HLA typing. Genet Med. 2015;17(10):807-814. doi:10.1038/gim.2014.195

83. Jutkowitz E, Dubreuil M, Lu N, Kuntz KM, Choi HK. The cost-effectiveness of HLA-B*5801 screening to guide initial urate-lowering therapy for gout in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;46(5):594-600. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.10.009

84. Kent R, Huber B. Gertrude Belle Elion (1918-99). Nature. 1999;398(6726):380-380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/18790

85. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1988. NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1988/press-release/

86. FDA adds Boxed Warning for increased risk of death with gout medicine Uloric (febuxostat). FDA drug safety communication. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published February 21, 2019. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-adds-boxed-warning-increased-risk-death-gout-medicine-uloric-febuxostat

87. Bisht M, Bist SS. Febuxostat: a novel agent for management of hyperuricemia in gout. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2011;73(6):597-600. doi:10.4103/0250-474X.100231

88. Sulfinpyrazone. MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. Updated June 15, 2017. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a682339.html

89. Probenecid. Prescribing information. Lannett Company, Inc. 2021. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=ab497fd8-00c3-4364-b003-b39d21fbdf38&type=display

90. Hemmersbach P. The Probenecid-story - A success in the fight against doping through out-of-competition testing. Drug Test Anal. 2020;12(5):589-594. doi:10.1002/dta.2727

91. Perishable. World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) Prohibited List | USADA. Published May 1, 2019. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.usada.org/athletes/substances/prohibited-list/?gad=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwz8emBhDrARIsANNJjS71Rf_P0EymCM5xDAwg2sS74_4kS9tb-fkv4arj4ldkMRbBEIpNSyMaApdDEALw_wcB

92. Waknine Y. FDA Approves pegloticase for refractory gout. Medscape. Published September 15, 2010. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/728557

93. Liu L, Liu S, Wang C, et al. Folate Supplementation for Methotrexate Therapy in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25(5):197-202. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000810

94. Huang IJ, Liew JW, Morcos MB, Zuo S, Crawford C, Bays AM. Pharmacist-managed titration of urate-lowering therapy to streamline gout management. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(9):1637-1641. doi:10.1007/s00296-019-04333-5

95. Feng X, Li Y, Gao W. Prophylaxis on gout flares after the initiation of urate-lowering therapy: a retrospective research. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(11):21460-21465

96. Jat N, DeSimone EM, McAuliffe R. Urate-Lowering Therapy for the Prevention and Treatment of Gout Flare. www.uspharmacist.com. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/uratelowering-therapy-for-the-prevention-and-treatment-of-gout-flare

97. Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, Chan KA. Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(4):437-443. doi:10.1592/phco.28.4.437

98. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(10):1447-1461. doi:10.1002/acr.21773

99. Low Purine Diet Explained with List of Foods to Eat or Avoid. Drugs.com. Updated April 2, 2023. Accessed April 16, 2023. https://www.drugs.com/cg/low-purine-diet.html

100. Arthritis.org. Published 2020. https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/nutrition/healthy-eating/which-foods-are-safe-for-gout

101. Ronquillo Y, Meyers A, Korvek SJ. Digital Health. [Updated 2023 May 1]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470260/

102. Serlachius A, Schache K, Kieser A, Arroll B, Petrie K, Dalbeth N. Association Between User Engagement of a Mobile Health App for Gout and Improvements in Self-Care Behaviors: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(8):e15021. doi:10.2196/15021

103. Gout Diagnosis app: diagnosing and treating Gout with evidence based medicine. iMedicalApps. Published June 14, 2016. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.imedicalapps.com/2016/06/gout-diagnosis-app-evidence-based-medicine/#

104. https://www.healthgrades.com/contributors/lorna-collier. Mobile Apps For Gout. Healthgrades. Published February 13, 2014. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.healthgrades.com/right-care/gout/mobile-apps-can-help-you-manage-gout

105. Health C for D and R. Device Software Functions Including Mobile Medical Applications. FDA. Published September 9, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications

106. 10 keys to mHealth apps that are easier to use. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/digital/10-keys-mhealth-apps-are-easier-use

107. Dickson A. Treatment and management of gout: the role of pharmacy. The Pharmaceutical Journal. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/treatment-and-management-of-gout-the-role-of-pharmacy

108. Managing gout in primary care: Part 1 – bpacnz. bpac.org.nz. https://bpac.org.nz/2021/gout-part1.aspx

109. Golenbiewski J, Keenan RT. Moving the Needle: Improving the Care of the Gout Patient. Rheumatology and Therapy. Published online March 2, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-019-0147-5

110. Haines A, Bolt J, Dumont Z, Semchuk W. Pharmacists' assessment and management of acute and chronic gout. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2018;151(2):107-113. doi:10.1177/1715163518754916

111. Hansten PD, Tan MS, Horn JR, et al. Colchicine Drug Interaction Errors and Misunderstandings: Recommendations for Improved Evidence-Based Management. Drug Saf. 2023;46(3):223-242. doi:10.1007/s40264-022-01265-1

112. Ford ES, Choi HK. Associations between concentrations of uric acid with concentrations of vitamin A and beta-carotene among adults in the United States. Nutr Res. 2013;33(12):995-1002. doi:10.1016/j.nutres.2013.08.008

113. Onder, M.E., Zengin, O. YouTube as a source of information on gout: a quality analysis. Rheumatol Int 41, 1321–1328 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04813-7

114. Alliance for Gout Awareness. goutalliance.org. Published November 14, 2022. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://goutalliance.org/

115. 5 Ways Pharmacists Can Show Empathy. Pharmacy Times. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/5-ways-pharmacists-can-show-empathy

116. Kleinstäuber M, Wolf L, Jones ASK, Dalbeth N, Petrie KJ. Internalized and Anticipated Stigmatization in Patients With Gout. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2(1):11-17. doi:10.1002/acr2.11095

117. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/diuretic-induced-hyperuricemia-and-gout. Updated March 2023. Accessed April 16, 2023.

118. Song WL, FitzGerald GA. Niacin, an old drug with a new twist. J Lipid Res. 2013;54(10):2586-2594. doi:10.1194/jlr.R040592

119. Ben Salem C, Slim R, Fathallah N, Hmouda H. Drug-induced hyperuricaemia and gout. Rheumatology. 2016;56(5):kew293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kew293