INTRODUCTION

“I’ve been shot, and I’ve been stabbed; nothing compares to gout pain.”

This is how Jim, a 77 year old man, describes his pain as he hobbles into the pharmacy to refill his prescription for colchicine. Jim complains that colchicine is not controlling his gout. He is wearing slippers that show his red swollen joint around his right big toe that is warm and painful to touch. Jim says his physician explained that these symptoms are due to podagra, uric acid crystallization and settling in the joint between his foot and big toe.1 As Jim speaks, his breath projects a strong alcohol smell.

Gout is the most common form of inflammatory arthritis affecting about 9.2 million adults in the United States (US) and is the result of hyperuricemia.2,3 Men are at higher risk of developing gout than women.4 Other risk factors include post-menopause, genetics, end-stage renal disease, and major organ transplant.

Uric acid overproduction, under-excretion, or both, elevate serum uric acid levels.5 Underexcretion of uric acid accounts for about 90% of gout cases.6 Human bodies produce uric acid as they break down dying tissues.4 Other sources of uric acid are foods high in purines, such as meats, seafood, and alcoholic beverages.7, 8 Ancient Greek history states that only rich people, who could afford these expensive foods, experience gout.9 Therefore, in the 5th century before Christmas (B.C.), people referred to gout as “the disease of kings.”10

PATHOGENESIS

Uric acid circulates in the blood as monosodium urate.11 In the kidneys, uric acid and urate undergo filtration and secretion into the filtrate followed by about 90% reabsorption into the blood.12 The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guideline defines hyperuricemia as serum uric acid of 6.8 mg/dL or greater, the level above which urate becomes insoluble in the blood.4

Gout results from the chronic deposition and crystallization of urate in the joints and tissues.4,13 Insoluble monosodium urate crystals form stone-like deposits, known as tophi, in soft tissues, synovial tissues, or bones.14,15 Tophi trigger an inflammatory response, which presents as an acute gout attack.15,16 However, hyperuricemia does not always result in gout.4

Although gout can affect any joint, initial attacks usually involve the big toe joint. Gout attacks are sudden and very painful.17 Acute gout attacks reach maximum pain level in 12 to 24 hours and may last 3 to 14 days if patients do not seek therapy.18 For this reason, all healthcare providers including those on pharmacy teams need to educate patients to seek medical care. Effective gout management reduces the risk of long-term complications like degenerative arthritis, urate nephropathy, infections, renal stones, joint fractures, and nerve or spinal cord impingement.19

DIAGNOSIS OF GOUT

Clinicians diagnose gout by collecting patient history, examining the patient, laboratory workup, and imaging.19 Uric acid crystals in the synovial fluid or tophi in tissues and/or bones confirm gout diagnosis regardless of the uric acid level.4

TREATMENT OF GOUT

The ACR guideline describes 3 treatment goals for patients with gout20:

- Terminating the acute gout attack

- Preventing future attacks

- Lowering the serum uric acid level

Terminating the Acute Gout Attack

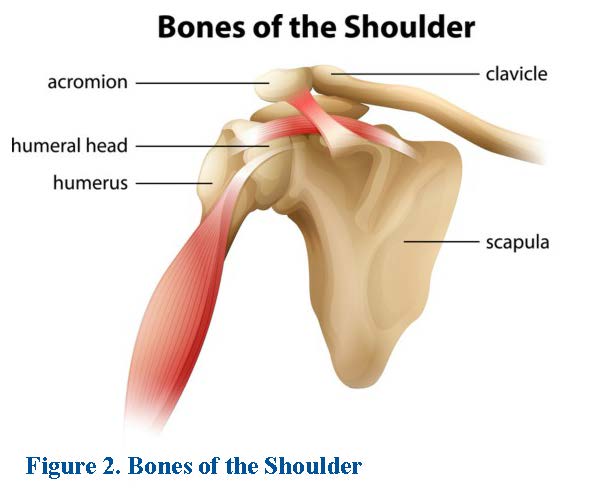

The ACR published the most recent guideline for the management of gout in 2020. The ACR guideline recommends colchicine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or glucocorticoids (oral, intraarticular, intramuscular) as first-line agents for the treatment of gout flares.20 Patient-specific factors guide the drug choice among the first-line agents. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) are alternative agents.20 If a first-line agent is ineffective, intolerable, or contraindicated, the ACR guideline recommends switching to another first-line agent before trying alternative agents. Topical ice is an adjunct to pharmacologic therapy. The severity of the gout flare guides the treatment duration.

Colchicine

Colchicine exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by binding to free tubulin dimers leading to microtubule polymerization inhibition, which affects cellular function.21, 22 Colchine has had an interesting history, as the SIDEBAR explains. Common side effects of colchicine are dose-dependent and include diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Because of its mechanism of action, toxic levels of colchicine inhibit cellular division leading to failure of multiple organs .22 Colchicine doses of 0.8 mg/kg are lethal.23 Colchicine undergoes extensive tissue distribution and therefore, a lower dose can be toxic in patients with liver or renal failure. Some unchanged colchicine undergoes renal excretion through glomerular filtration and therefore, requires dosage adjustment for renal dysfunction.21, 24 Cytochrome P450 3A4 hepatic enzymes metabolize colchicine.21, 25 P-glycoprotein facilitates colchicine removal from the body.26 Co-administration of medications that inhibit CYP3A4 enzyme activity (example: grapefruit juice, azole antifungals, erythromycin, verapamil) increase the risk of colchicine toxicity.21, 25 In addition, co-administration of colchicine with P-glycoprotein inhibitors (example: digoxin) increases the risk of colchicine toxicity.26 Toxic symptoms are dose-dependent with increasing severity.27 Patients with toxicity may present with gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), hypotension, lactic acidosis, or acute kidney injury.22, 27 To decrease the risk of toxicity, colchicine’s prescribing information recommends avoiding its co-administration with P-glycoprotein inhibitors or CYP3A4 inhibitors in patients with renal or hepatic impairment.28 For other patients, the prescribing information recommends weighing risks versus benefits before co-administering colchicine with medications that pose a significant drug interaction.

SIDEBAR: HISTORY OF COLCHICINE

Colchicine is derived from a plant, Colchicum automnale.29 Other names for this plant include Autumn Crocus, meadow saffron, naked lady, and colchicum.30 Ebers Papyrus, an Egyptian medical document on herbs dating back to 1500 BC, indicates the use of C. automnale for joint pain.31 In 1833, a German pharmacist analyzed the substance and gave it the name colchicine.29 In France, in 1819, a chemist and a pharmacist isolated colchicine from the plant. In 1884, a French pharmacist produced and sold colchicine as 1 mg granules, which is still available in some countries.29,32 Colchicine accounts for about 0.1-0.6% of the plant content.33 Non-surprisingly, the C. automnale plant is poisonous. Humans should not ingest the plant. Symptoms of C. automnale toxicity resemble the side effects or toxicity of colchicine.34 These symptoms range from diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting to organ failure and death.

Colchicine was available for decades in the US without a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved labeling.35 Despite the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act requiring the FDA to approve medications based on efficacy and safety data, colchicine was grandfathered in. Grandfathered drugs were medications available on market before the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act of 1938 or its amendments in 1962.

In 2006, the FDA initiated the unapproved drug initiative (UDI).36 The goal of the UDI program was to decrease the number of medications in the United States that do not carry FDA approval. Under the UDI program, the FDA allowed exclusive marketing to manufacturers who obtain FDA approval. Some pharmacists and pharmacy technicians may recall colchicine shortage as manufacturers of colchicine received warning letters from the FDA to stop selling colchicine.37 Mutual Pharmaceutical Company submitted a new drug application (NDA) for colchicine in November 2008.38 The UDI did not require manufacturers to conduct new clinical trials to obtain FDA approval. Mutual Pharmaceutical Company’s NDA included data from randomized controlled trials in 1974 and 2004 that proved the safety and efficacy of colchicine. As a result, in July 2009 the FDA approved colchicine for the treatment of gout and familial Mediterranean fever. Colchicine came back to the US market under brand name Colcrys.39

Colchicine is light sensitive. Pharmacies should protect colchicine from light and dispense it in a light-resistant container.28 The FDA requires pharmacies to distribute a medication guide to patients when dispensing colchicine.40 Medication guides inform patients of potential serious adverse reactions and harm mitigation strategies. The Institute for Safe Medical Practices (ISMP) lists colchicine on the look-alike sound-alike (LASA) list due to potential for confusion with Cortrosyn, which is the brand name for cosyntropin.41 Of note, cosyntropin is a synthetic adrenocorticotropin hormone that has anti-inflammatory properties and is an alternative agent for gout attacks.42 In patients with a history of gout, the ACR guideline recommends a “medication-in-pocket” (discussed below) approach to allow early initiation of an anti-inflammatory drug at the onset of a gout flare.20 Since colchicine has anti-inflammatory properties, it is an option for the “medication-in-pocket” approach.

The pharmacist takes a close look at Jim’s prescription refill history to figure out why colchicine is not working for Jim. The pharmacist explores several possibilities:

- Is Jim adhering to his urate-lowering therapy (ULT)?

- Is Jim refilling his colchicine as part of a gout flare prophylactic therapy upon initiating ULT?

- Is Jim asking for colchicine as a “medication-in-pocket” approach?

- Is Jim consuming excessive alcohol?

- Is Jim eating foods rich in purines?

- Is Jim taking any prescription or over-the-counter medications that may increase his uric acid level?

NSAIDs

The FDA has approved indomethacin, naproxen, and sulindac for the treatment of acute gout flare.43,44, 45 However, the guideline does not recommend a specific NSAID.20 Choice of agent depends on patient-specific factors including cardiovascular (CV) risk, gastrointestinal (GI) risk, cost, and availability without a prescription.46 Celecoxib is a selective cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor and therefore carries a low GI risk but is associated with a dose-dependent increase in CV risk.47, 48 Ibuprofen carries a low GI risk. Indomethacin, naproxen, diclofenac, and sulindac carry a moderate GI risk.49, 50 Among the nonselective NSAIDs, CV risk is highest with diclofenac and lowest with naproxen.51 Despite differences in CV risk among nonselective NSAIDs, the FDA mandates a boxed warning for all NSAIDs about increased risk of thrombosis, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke.52, 53 In addition, the FDA requires pharmacies to distribute a medication guide to patients when dispensing a prescription for NSAIDs.54 Any NSAID is an option for the “medication-in-pocket” approach.20

Glucocorticoids

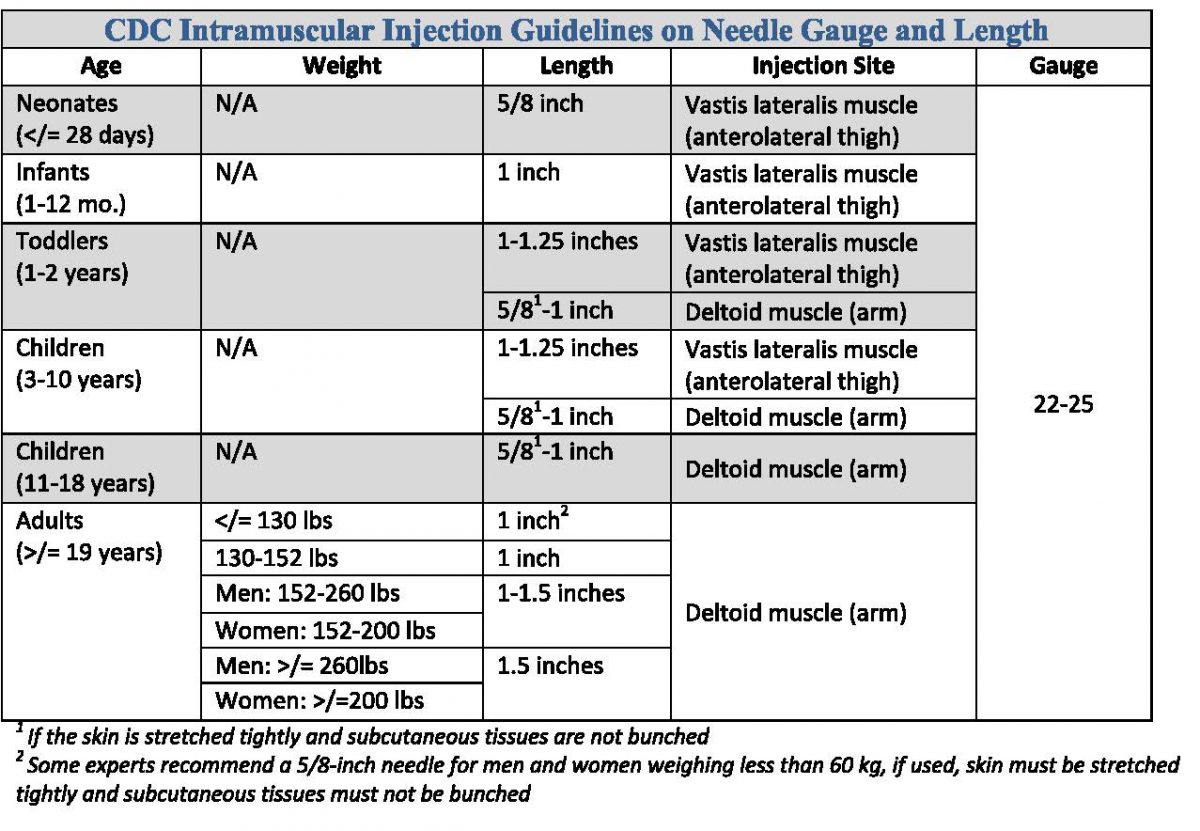

The ACR guideline does not recommend a specific oral glucocorticoid.20 Parenteral glucocorticoids (intramuscular, intravenous, or intraarticular) are alternative options for patients who cannot tolerate oral therapy. Glucocorticoids (example: prednisone, methylprednisolone) are an attractive option for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) or those who cannot tolerate colchicine or NSAIDs.1,55 Short-term glucocorticoids do not cause significant side effects.56, 57 Glucocorticoids are an additional option for the “medication-in-pocket” approach, including injectable formulations for patients who cannot take oral medications.20 Methylprednisolone is available in different dosage forms such as oral, intramuscular (as acetate or succinate), intravenous (as acetate), and intraarticular (as acetate).58

Anakinra

Anakinra is an IL-1 receptor antagonist.59 It blocks the activity of the inflammatory mediatory IL-1. Anakinra has an off-label indication for gout attacks at a dose of 100 mg subcutaneously daily for 3 to 5 days.60, 61 The ACR guideline classifies anakinra as an alternative agent, particularly due to cost.20 The manufacturer recommends storing anakinra in the refrigerator and protecting from light until ready for administration.62 Patients can self-administer anakinra after demonstrating proper administration technique.59

ACTH

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) binds to melanocortin receptors, which triggers the release of endogenous steroids, thus decreasing inflammation.63 The ACR guideline recommends ACTH as an alternative agent.20,63 ACTH is available as an intramuscular or subcutaneous injection.64 The purified cortrophin formulation carries an indication for acute gouty arthritis.65 The manufacturer does not provide a dosing recommendation specific for gout and recommends caution in patients with renal insufficiency.64-66 The manufacturer recommends storing ACTH in the refrigerator until ready for administration and warming to room temperature before injecting.67

Table 1 summarizes the first-line agents for the treatment of gout flares.

| Table 1. First-line Agents for the Treatment of Gout Flares20, 24, 44-46, 56, 68-71 |

| Therapy |

Dose |

Comment |

Monitoring parameters |

| Colchicine |

· Day 1 of therapy: Use treatment dose of 1.2 mg by mouth (PO) as soon as possible then 0.6 mg after one hour. Maximum dose 1.8 mg/day.

· Day 2 and until flare resolves, use prophylactic dose of 0.6 mg PO once or twice daily. |

If creatinine clearance (CrCl) < 30 mL/min:

· Use 1.2 mg PO as soon as possible then single dose of 0.6 mg after one hour. Avoid repeating therapy within a 14-day period.

· Alternatively, use 0.3 mg PO as soon as possible as a single dose. Avoid repeating therapy within 3-7 days.

If patient is on dialysis:

· Use 0.6 mg PO as a single dose. Avoid repeating therapy within a 14-day period. |

Monitor patients with CrCl ≤ 80 mL/min closely for adverse effects. |

| NSAIDs

|

· Indomethacin: 50 mg three time daily until pain is tolerable (usually, 3 to 5 days).

· Sulindac: 200 mg twice daily until attack resolves (usually, 7 days).

· Naproxen: 750 mg x 1 dose then 250 mg every 8 hours until attack resolves (usually, 2 days). |

· The manufacturer does not provide recommendations for renal dosage adjustment.

· The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommends avoiding use of NSAIDs If CrCl < 30 mL/minute. |

Monitor GI, renal, and CV toxicity in elderly patients.

Prescribe lowest effective dose for the shortest duration possible. |

| Glucocorticoids |

· Follow specific glucocorticoid dosing recommendation. |

Safest option in patients with CKD. |

Monitor serum glucose, blood pressure, electrolytes, mood changes, and recurrent infections. |

Interestingly, a panel consisting of eight patients with gout participated in the development of the 2020 ACR guidelines.20 The patient panel provided valuable input from a patient perspective regarding therapy preference for patients with an established gout diagnosis. The patient panel strongly favored a medication-in-pocket approach for the treatment of acute gout flares. With this approach, the clinician prescribes an anti-inflammatory medication that the patient keeps on hand for use as needed.72 Moreover, the patient panel favored an injectable dosage form for the medication-in-pocket to control the pain faster in patients who can take nothing by mouth. The medication-in-pocket approach ensures that patients have quick access to an anti-inflammatory medication at the first onset of gout attack symptoms.20

Jim’s colchicine regimen is consistent with the “medication-in-pocket” to treat an acute gout flare.

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC GOUT

The goal of chronic gout management is to lower the serum uric acid level with ULT, if indicated, and to prevent future attacks.20 ULT includes medications that decrease uric acid production or promote uric acid excretion.73 The ACR 2020 guideline recommends a “treat-to-target” approach that guides ULT dose titration and maintenance to achieve serum uric acid of less than 6 mg/dL.20 Lower ULT initial dosing with subsequent titration decreases the risk of gout flare associated with ULT initiation.20

Pause and Ponder: What patient factors determine eligibility for urate lowering therapy (ULT)?

Table 2 provides recommendation on initiation of ULT based on patient-specific factors.

| Table 2 - Indication for ULT 20 |

| Patient factors |

2020 ACR guideline recommendation |

Comment |

| ≥1 subcutaneous tophi |

ACR guideline strongly recommends initiating ULT |

Moderate or high certainty of evidence that benefits of ULT consistently outweigh the risks |

| Gout-attributable radiographic damage |

| ≥2 gout flares per year |

| > 1 flare but < 2 flares per year |

ACR guideline conditionally recommends initiating ULT |

Low certainty of evidence or no data available and/or benefits and risks closely balanced |

| First flare and any of the following:

· Chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage ≥ 3

· Serum uric acid > 9 mg/dL

· Urolithiasis |

| First gout flare |

ACR guideline conditionally recommends against initiating ULT |

| Asymptomatic hyperuricemia* |

*Serum uric acid > 6.8 mg/dL

Pause and Ponder: Which urate-lowering agent is first-line therapy?

Table 3 summarizes urate-lowering medications.

| Table 3 - Urate Lowering Medications 20,74-76 |

| Pharmacological class |

Mechanism of action |

Medication |

Comments |

| Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors |

Inhibition of xanthine oxidase resulting in decreased conversion of hypoxanthine to xanthine and xanthine to uric acid. |

Allopurinol

Febuxostat |

· Allopurinol is first-line agent.

· Start allopurinol at ≤ 100 mg/day in normal kidney function and ≤ 50 mg/day in CKD stage ≥ 3 then titrate.

· Start febuxostat at ≤ 40 mg/day then titrate.

|

| Uricosuric Agents |

Inhibition of urate reabsorption in the renal tubules resulting in increased excretion of uric acid in the urine. |

Probenecid |

· ACR guideline strongly recommends XOI over probenecid for patients with CKD stage ≥ 3

· Start probenecid at 500 mg PO once or twice daily then titrate. |

| Urate Oxidase Enzyme |

Catalysis of uric acid oxidation to water-soluble allantoin resulting in increased excretion of the allantoin in the urine. |

Pegloticase |

· ACR guideline strongly recommends against use of pegloticase as a first-line agent

· Administer pegloticase 8 mg IV infusion every 2 weeks along with methotrexate 15 mg PO once a week with a folic acid supplement.

· Start weekly methotrexate and folic acid supplementation 4 weeks before initiating pegloticase and continue while on pegloticase. |

Clinicians usually determine eligibility for ULT when patients present with an acute gout attack.20 Some experts favor initiating ULT two to four weeks after the resolution of a gout attack.77 One reason for this practice stems from the fear of gout attack worsening with ULT initiation. The other reason is the perception that during a gout attack, patients are in too much pain to process information regarding chronic therapy. However, the ACR guideline favors initiating ULT during a gout flare as patients may not return for a follow-up visit to initiate ULT after the flare resolves.20

XANTHINE OXIDASE INHIBITORS (XOIs)

XOI include allopurinol and febuxostat.20 XOI are first-line among urate-lowering agents, and the guideline recommends allopurinol as a first-line agent for all patients with gout, unless contraindicated.

Allopurinol

Allopurinol is associated with an increased risk of allopurinol hypersensitivity syndrome (AHS), a rare but severe, and potentially life-threatening adverse reaction.78 AHS presents as fever, severe rash, eosinophilia, hepatitis, and acute kidney injury.79 AHS is more common in patients who are African Americans or of Southeast Asian descent.78 Pharmacogenetic studies show that these patients have a gene on their human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system that increases the risk of developing AHS. This gene is the HLA-B*5801 allele.80 The interaction of allopurinol with the HLA-B*5801 allele triggers an immune reaction characterized by T-cell activation.81 Not all patients who are positive for HLA-B*5801 allele develop AHS.82 Risk of AHS increases in HLA-B*5801 allele positive patients who have elevated allopurinol serum level due to dose increase or renal dysfunction.81

In the US, testing for HLA-B*5801 in Caucasians or Hispanics is not cost-effective.83 The 2020 ACR guideline recommends genetic testing for the HLA-B*5801 allele before starting allopurinol for patients who are African Americans or of Southeast Asian descent.20 The guideline recommends starting allopurinol at a low dose of 100 mg daily for normal renal function and a lower dose in case of renal dysfunction.

The prescribing information recommends protecting allopurinol from light.74 ISMP lists the brand name of allopurinol, Zyloprim, on the look-alike sound-alike (LASA) list due to potential for confusion with zolpidem.42

SIDEBAR: DID YOU KNOW THAT THE DISCOVERY OF ALLOPURINOL LED TO A NOBEL PRIZE AWARD?

Gertrude Elion, who earned a master’s degree in chemistry from New York University in 1941, worked as a lab assistant for George Hitchings. Up until the 1950s, scientists produced medications by screening and modifying naturally existing substances.84 However, Elion and Hitchings’ contribution to medicine was groundbreaking to drug development as they introduced drug therapy that was targeted to specific cells. In 1963, Elion and Hutchings discovered that allopurinol blocked the synthesis of uric acid. In 1988, the Nobel Prize Committee awarded Gertrude Elion and George Hitchings the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of allopurinol and other medications.85

Febuxostat

Febuxostat carries a boxed warning for increased risk of CV death in patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), when compared to allopurinol.86 Therefore, the 2020 ACR guideline recommends selecting another ULT medication in patients with established CVD.20 For patients who experience a CV event while on febuxostat, the ACR guideline recommends switching to a different ULT medication.20 The FDA requires pharmacies to distribute a medication guide when dispensing febuxostat to patients.86

URICOSURICS

Probenecid

Probenecid is the only uricosuric drug approved in the United States.87,88 Probenecid may cause nephrolithiasis (uric acid stones in the kidneys).89 These uric acid stones form as the uric acid crystallizes in an acidic urine. The prescribing information for probenecid recommends adequate hydration and adjunct urine alkalinizing agents (example: sodium bicarbonate or potassium citrate).89 However, the 2020 ACR guideline determined insufficient evidence to recommend the routine use of alkalinizing agents with probenecid.20 Probenecid is usually an add-on therapy in patients with partial response to an XOI. Remember to counsel patients on adequate hydration to decrease the risk of nephrolithiasis.

ISMP lists probenecid on the LASA list due to potential for confusion with Procanbid, the brand name for procainamide, an antiarrhythmic drug.42 Probenecid also has some interesting abuse potential (see the SIDEBAR).

SIDEBAR: CAN PROBENECID HELP ATHLETES IMPROVE PERFORMANCE?

Random drug testing in sports led athletes to misuse probenecid to mask the unlawful use of performance-enhancing drugs such as anabolic-androgenic steroids.90 Probenecid inhibits the tubular secretion of anabolic-androgenic steroids in the kidneys, thus inhibiting their excretion in the urine. As a result, urine drug testing will not detect the use of these illegal substance, and athletes can pass the random drug testing successfully. In 1986, a doping control officer traveled from Norway and collected 6 urine samples from 6 Norwegian athletes who were training in the US. The athletes showed up at least 1.5 hours late probably to allow time for onset of action of the masking agent. Five of the samples showed an unusually dilute urine with low specific gravity. In addition, the concentration of endogenous androgenic-anabolic steroids in the urine samples was at least 100 times below normal.90 These unusual findings along with suspicious behaviors projected by the athletes during the testing process, triggered further analysis of the urine samples. The lab identified a “new masking agent”, probenecid and its metabolite, in these urine samples. Today, probenecid appears on the World Anti Doping Agency (WADA) prohibited list.91 The WADA list serves as a standard for identifying substances that athletes may illegally use to enhance performance in sports.91

URATE OXIDASE ENZYME

Pegloticase

The FDA approved pegloticase for adults with chronic gout refractory to conventional therapy.92 The 2020 ACR guidelines recommends switching to pegloticase when XOIs, probenecid, and other interventions fail.20 In clinical trials, administering methotrexate with pegloticase increased the chance of tophi resolution by 22.8% compared to pegloticase monotherapy.76 Therefore, pegloticase’s prescribing information recommends co-administration with methotrexate, unless contraindicated. Folic acid supplementation decreases the risk of hepatotoxicity and GI side effects associated with methotrexate.93 Pharmacists should counsel patients about the importance of adherence to folic acid while on methotrexate.

The manufacturer recommends storing pegloticase in the refrigerator and protecting it from light before dispensing.76 After diluting pegloticase for IV infusion in an institutional setting, healthcare workers should protect the solution from light.

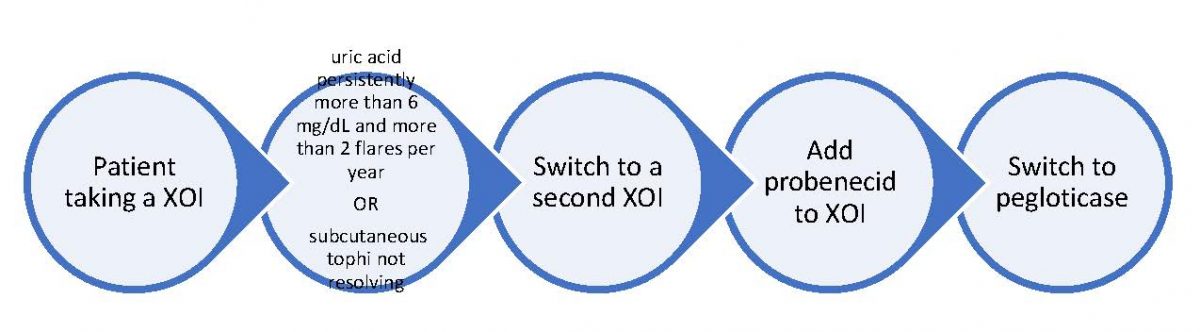

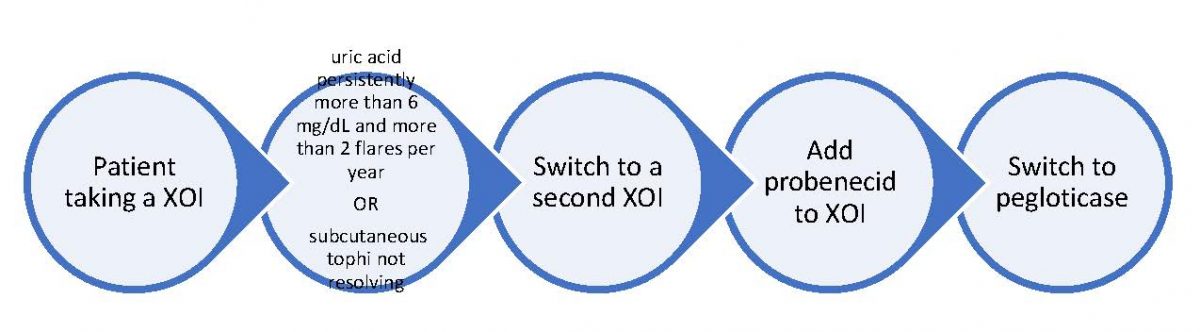

Pause and Ponder: When does the guideline recommend switching urate-lowering agents?

The 2020 ACR guideline recommends using the maximum tolerated or recommended dose of a ULT.20 Figure 1 outlines the management of patients taking a XOI requiring adjustment to therapy:

Figure 1. Switching ULT

Jim’s medication profile reveals that he has been taking allopurinol for little over a year now.

DURATION OF THERAPY

For patients tolerating ULT, the 2020 ACR guideline recommends indefinite therapy to avoid worsening gout and its associated complications.20 Patients may not adhere to therapy due to cost, pill burden, and low health literacy.94 Remember to counsel patient on adherence and goals of ULT as patients may think they do not need to take ULT if they have no symptoms.

PREVENTING GOUT FLARE UPON INITIATION OF ULT

Initiation of ULT may trigger a gout flare due to activation of crystals precipitated in joints.95, 96 The risk of gout flare increases with higher reduction in serum uric acid levels. Studies suggest that gout attacks associated with ULT may decrease patient adherence to ULT.97 Prophylaxis with anti-inflammatory medications decreases the risk of gout flare upon ULT initiation. The 2020 ACR guideline recommends prophylactic therapy upon initiating ULT and for at least three to six months. Patients who continue to experience flares may require a longer duration of prophylactic therapy.20 Experts recommend colchicine or NSAIDs as first-line prophylactic therapy.98 Table 4 summarizes prophylactic medications and recommendations.

| Table 4 – Medications that Prevent Gout Attack with ULT Initiation |

| Medication |

Recommendation |

| Low-dose colchicine |

Use 0.6 mg once or twice daily |

| Low-dose NSAIDs |

Use naproxen 250 mg or equivalent dose of different NSAID

Add proton pump inhibitor if indicated |

| Low-dose prednisone or prednisolone |

Use less than or equal to 10 mg per day

Reserve corticosteroids for patients who cannot tolerate colchicine and NSAIDs |

NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY AND LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS

Serum uric acid levels decrease only slightly with dietary modifications.20 In addition, certain diets may trigger a gout flare. To decrease the risk of flares, the 2020 ACR guideline conditionally recommends the following approaches:

- Limiting alcohol intake

- Limiting purine intake. Some examples of high-purine foods include seafood like sardines, tuna, haddock, and meats like bacon, turkey, veal, and liver.99, 100

- Limiting high-fructose corn syrup intake

- Following a weight loss program if the patient is overweight or obese

Jim projected an alcohol breath when speaking. Jim may be consuming excessive amounts of alcohol. He may be consuming a non-gout friendly diet.

DIGITAL HEALTH AND GOUT MANAGEMENT

Digitalization of health care is rapidly evolving and involves the use of technology to manage health conditions, ameliorate modifiable risk factors, and promote health and wellness.101 Wearable devices such as fitness trackers, patient portals, and mobile apps are only few examples of digital health tools. Investigators suggest that gout mobile health apps may improve patient perception of the disease, clarify beliefs, and benefit self-care.102 However, further studies are essential to prove these mobile applications beneficial. As of this writing, several gout-related mobile health applications are available. Target users for these applications can be clinicians or patients. For example, a physician developed a mobile application called Gout Diagnosis. The application includes an evidence-based algorithm to facilitate an accurate diagnosis of gout.103 On the other hand, patients can download from a variety of existing gout mobile applications at little or no cost.104 The National Kidney Foundation developed a mobile application called Gout Central. This application comes from a reputable foundation and provides patient education on symptoms and risk factors for gout, nonpharmacologic recommendations such as diet and lifestyle modifications, and medications to treat gout and prevent flares.104 The FDA does not regulate mobile medical applications.105 Therefore, the choice of mobile health application depends on patient preference such as cost, ease of use, compatibility, security, and type of content.106

A mobile application may help Jim learn about foods and drinks that may trigger gout attacks.

PHARMACY TEAM IMPACT ON GOUT MANAGEMENT

Pharmacists are the most accessible healthcare professionals. Patients with a gout flare may seek pharmacists for recommendations on pain management. When patients without a previous gout diagnosis present to the pharmacy, pharmacists may recognize signs of gout and refer them to their primary care clinician. Pharmacists can educate patients who have a diagnosis for gout about the phases and goals of gout therapy, including the likelihood that ULT will be a lifelong therapy.

Pharmacists are well-positioned to assess adherence to ULT and educate patients about the importance of ULT.107 Pharmacists can assess patient understanding of various therapies and remind them that anti-inflammatory medications treat acute gout attack or prevent gout flare upon initiating ULT. Pharmacists should empower patients to request from their clinician a medication-in-pocket prescription. Pharmacists should counsel patients on the proper use of medication-in-pocket by reminding them to take the anti-inflammatory medication as soon as possible, ideally within 12 hours of onset of a gout attack.108 In addition, patients may need a reminder about continuing their ULT while taking the medication-in-pocket for acute flares.109

Pharmacy technicians can ensure that patients have refills on their medication-in-pocket prescription to facilitate early initiation. Updating the patient’s records in the pharmacy software with the gout diagnosis can facilitate this continuity of care. The pharmacy team should encourage patients to fill all their prescriptions at the same pharmacy. Through access to all the patient’s medications, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can play a crucial role in optimizing gout management by identifying medications that increase serum uric acid levels.110

In addition, the pharmacy team can identify potential drug-drug interactions. This is particularly important with colchicine as it is a substrate for CYP3A4 and P-gp and has a narrow therapeutic window.111 In addition, some medications are known to increase serum uric acid levels.20 Advising patients to check with the pharmacy team before purchasing an over-the-counter (OTC) medication can decrease the use of inappropriate medications. When completing transactions at the register, pharmacy technicians are well positioned to identify OTC products that can worsen gout, such as vitamin A or niacin.112 On the other hand, frequent purchase of OTC anti-inflammatory medications like naproxen or ibuprofen may imply uncontrolled gout.

Patients can find educational videos on YouTube to learn more about gout therapy and appropriate diet.113 Additional resources are available to patients on goutalliance.org. These include videos, podcasts, guides, and awareness events.114 Some patients may like to learn about their condition using gout-related mobile applications.

Pharmacy interns may benefit in hearing from patients about their experience with gout, especially the debilitating pain. This may help future pharmacists empathize and develop better relationships with patients, which can improve patient outcomes.115

The entire pharmacy team could engage in alleviating misconceptions about gout. Some patients with gout have reported stigma regarding their condition from friends, family members, and healthcare workers.116 Some patients with gout have even reported an internalized stigma. Stigmatization may be due to the misbelief that gout is benign, preventable, or self-inflicted.

Did you know that May 22 is National Gout Awareness Day?

Jim states that he feels embarrassed about wearing slippers that expose his swollen toe. The pain is so intense that he is unable to tolerate a close-toe shoe.

Table 5 summarizes some medications that may increase serum uric acid level.

| Table 5 – Managing Medications that Increase Serum Uric Acid Level and Risk of Gout Attack20,110,117-119 |

| Medication |

Mechanism |

Recommendation |

| Loop and thiazide diuretics

Use: hypertension, edema

|

Decrease urate excretion |

The guideline recommends switching to a different antihypertensive and suggests losartan when feasible.

|

| Aspirin (low-dose, 81 mg)

Use: prevention of CVD |

Increases uric acid renal reabsorption and decreases secretion |

The guideline conditionally recommends against discontinuing low-dose aspirin with appropriate indication. |

| Niacin

Use: dietary supplement |

Inhibits the enzyme uricase, thus inhibiting the oxidation of uric acid, or decreases uric acid excretion |

The guideline does not provide a specific recommendation for niacin-induced hyperuricemia. Experts recommend adequate hydration. |

After looking into Jim’s medication profile and inquiring about his OTC products, the pharmacist does not identify any medication that may be increasing his serum uric acid level.

CONCLUSION

Gout is the most common type of inflammatory arthritis. Untreated gout can lead to complications such as degenerative arthritis, urate nephropathy, infections, renal stones, joint fractures, and nerve or spinal cord impingement. ULT is indicated for chronic gout management. Allopurinol is the first-line urate-lowering agent. Colchicine, NSAIDs, and corticosteroids are indicated for acute flares, and, in lower doses, for gout flare prophylaxis upon initiating ULT. Diet and lifestyle modifications complement the pharmacologic therapy. The pharmacy team plays a crucial role in identifying drug-induced hyperuricemia and educating patients about the importance of adherence to ULT. Gout flares are painful and debilitating. Pharmacists can recommend initiation of anti-inflammatory therapy for acute gout flares. Pharmacy technicians can ensure patients have refills for their anti-inflammatory medication to facilitate the medication-in-pocket approach.

Jim’s uncontrolled gout may be due to various reasons that pharmacy team can investigate. Inquiring about Jim’s drinking habits and educating him about the negative impact of alcohol on gout management is a necessary first step in his therapy. If an adequate trial of dietary changes does not control his symptoms, then switching to a different XOI or adding probenecid, depending on what he has tried so far, would be appropriate.