Learning Objectives

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

| · Recall the mechanism of action and dosing schedule of GLP-1 receptor agonists |

| · Classify adverse reactions most commonly associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists |

| · Discuss GLP-1 receptor agonists indications for use |

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to

| · Identify the different formulations of GLP-1 receptor agonists |

| · Classify storage requirements for GLP-1 receptor agonists |

| · Review GLP-1 receptor agonists indications for use |

Release Date: June 17, 2023

Expiration Date: June 17, 2026

Course Fee

Pharmacists: $5

Pharmacy Technicians: $2

There is no grant funding for this CE activity

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-23-020-H05-P

Pharmacy Technician: 0009-0000-23-020-H05-T

Session Codes

Pharmacist: 23YC20-XFT68

Pharmacy Technician: 23YC20-TXF84

Accreditation Hours

1.5 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-23-020-H05-P/T will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Jennifer Kuivinen, RPh, CIP

Pharmacist

Meijer Pharmacy

Petoskey, MI

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Jennifer Kuivinen does not have any financial relationships with ineligible companies and therefore has nothing to disclose.

ABSTRACT

Recently, it’s a rare day when the national news outlets and social media platforms don’t discuss medication-assisted weight loss. Semaglutide has become a social media sensation for its ability to help people–even people who do not have diabetes (its approved indication) lose weight. With celebrities reporting significant weight loss with off-label use of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, pharmacy teams are fielding questions and juggling prescriptions to deal with drug shortages. This continuing education activity provides basic facts about using GLP-1 receptor agonists for weight loss.

CONTENT

Content

INTRODUCTION

Lifestyle modifications have been the mainstay of weight management for years. We’ve all heard the advice: Exercise more, eat less, limit fried foods and sugary drinks, and the weight should slowly disappear. As the weight comes off, you might have some setbacks but just keep tracking your foods and your success is right around the corner.

If only it was that easy!

Scroll any social media platform today and search the term, “#ozempicweightloss” and a plethora of joyful testimonials appear. Some videos have reports of people losing 17 pounds in 3 months or 64 pounds in a year with no cravings for food. “I can eat whatever I want!!” cried a satisfied user. It is as if the golden ticket has been found in all the candy bars ever produced and everyone is going to the candy factory!

Although the recent media emphasis has been on semaglutide, and the Ozempic product primarily, other glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists have also been associated with weight loss to varying degrees. This continuing education activity’s primary focus is to clarify misinformation, highlight specific GLP-1s’ risks and benefits when used for weight loss, and answer frequently asked questions.

WHAT ARE GLP-1 RECEPTOR AGONISTS?

Major breakthroughs in the physiology of the pancreas occurred in the early 1900s.1 At that time, physiologists thought the nervous system had exclusive control of all bodily functions. That idea changed when two scientists, William Bayliss and Ernest Starling, discovered a chemical compound they named secretin. Released from intestinal mucosa, secretin stimulated the pancreas.2 Shortly after the discovery of the hormone insulin in 1921, research being conducted at the time primarily stimulated the pancreas to produce insulin by administering glucose via the intravenous route. However, when glucose was administered orally (allowing nutrients to travel to gastrointestinal areas), insulin levels improved substantially. This observation was known as the incretin effect. As a result, two insulinotropic hormones were later identified as incretin hormones, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) discovered in 1971 and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) discovered in 1985.1,2

Analyzing the venom of the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) in 1990, endocrinologist Dr. John Eng discovered a peptide that stimulated insulin release from the pancreas.3 Named exendin-4, this peptide was similar in structure and function to GLP-1 found in humans. One problem with GLP-1 was that when it is released into the body, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4). quickly inactivated it. Researchers then developed the DPP-4 inhibitors to allow GLP-1 to remain active for a longer period of time. However, synthetically producing GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) directly has extended the peptide’s life. Initial development resulted in twice daily and then daily administration (half-life of 13 hours) of GLP-1RAs. However, when researchers combined semaglutide with a free fatty acid side chain that was tightly bound to albumin, its half-life was increased substantially. The resultant half-life of 165 hours led to an advantageous injection administration schedule for semaglutide: once weekly.3,4,5

Mechanism of Action

As a class of medications, all GLP-1RAs share common mechanisms of action in the treatment of diabetes: stimulate the pancreas to secrete insulin, suppress the action of glucagon, and decrease gastric emptying.4 Scientists previously studied the effects of GLP-1 and noticed that the protein, when injected in rats, decreased appetite quickly.5 Once clinicians began using GLP-1RAs to treat diabetes in humans, they also observed weight loss due to decreased appetite, increased feelings of fullness, and reduced caloric consumption.4

Researchers determined that the brain contained GLP-1 receptors. Weight loss was due to GLP-1RAs ability to travel to these receptors and influence specific areas of the hypothalamus that are key to controlling appetite, calorie consumption, satiety, and body weight.4 Among GLP-1RAs, semaglutide and liraglutide stimulate the highest amount of weight loss success.

Comparison of GLP-1 drugs

Table 1. GLP-1RAs for Weight Loss

| Medication | Dosing | Counseling points | Supplies needed for injection |

| Semaglutide (Wegovy) | Adult and pediatric patients aged 12 and older, starting dosage at 0.25 mg injected subcutaneously once weekly.

Weeks 1-4: 0.25 mg Weeks 5-8: 0.5 mg Weeks 9-12: 1 mg Weeks 13-16: 1.7 mg Weeks 17 & forward: 2.4 mg maintenance dose once weekly.

|

If adverse reactions occur during the upward titration period, consider delaying increase in dosage for four weeks.

Consider discontinuing the drug if patients do not lose at least 5% of baseline body weight within 3 months |

1 alcohol swab or soap and water

1 gauze pad or cotton ball

1 sharps disposable container for used Wegovy pens |

| Liraglutide

(Saxenda) |

Adults and pediatric patients aged 12 and older, starting dosage at 0.6 mg injected subcutaneously once daily. (NOTE: This is a DAILY dose)

Week 1: 0.6 mg Week 2: 1.2 mg Week 3: 1.8 mg Week 4: 2.4 mg Week 5 & forward: 3 mg maintenance dose daily.

|

If adverse reactions occur during upward titration period, consider delaying dose increase for approximately one additional week.

Patients can continue on maximally tolerated dose if goal weight loss achieved on that dose.

|

Soap and water

Pen needle: 8 mm (Novofine or NovoTwist)

1 sharps disposable container for pen and needles |

Adverse Drug Reactions and Boxed Warning

GLP-1 agonists all have similar and common gastrointestinal adverse effects (nausea [~15–30%], vomiting [~10-15%], diarrhea [~5-10%], abdominal pain, constipation).6,7,8 Patients can use some strategies to possibly mitigate these adverse effects6,7,8:

- Increasing the GLP-1 agonist dose slowly

- Staying hydrated and increasing fiber

- Avoiding high-fat foods and alcohol

- Stopping eating when full (and eating only when hungry)

- Spacing meals appropriately

- Using short-term proton pump inhibitors or H2 blockers if needed

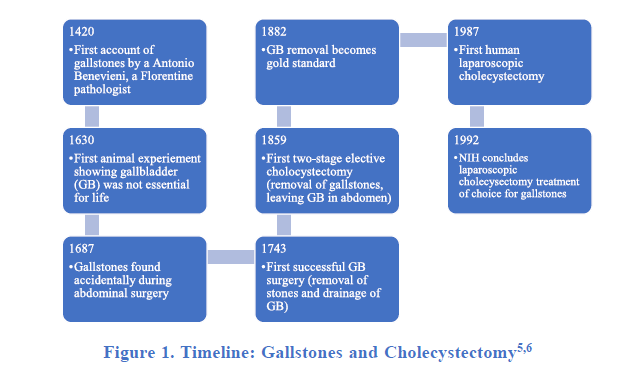

Patients may also experience headache, fatigue, dyspepsia (gastrointestinal upset), dizziness, abdominal distension, eructation (burping), hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes, flatulence, gastroenteritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease.7 Clinicians should evaluate patients for gallbladder disease if cholelithiasis (gallstones) or cholecystitis (an inflamed gall bladder) is suspected.

Reports of patients experiencing hair loss have surfaced recently from news and social media. Listed as an adverse reaction for Wegovy, but not for Ozempic, the Wegovy dose is much higher for treatment of weight loss.9 Some clinicians think that the rapid loss of weight triggers the body to conserve calories consumed for essential functions.9 Since patients eat less while taking the medications, their diet may consist of lower amounts of protein and minerals important for hair growth. Clinicians have seen hair growth resume once the body reaches a plateau in weight loss, therefore the loss of hair is not permanent.9

These drugs also share a boxed warning for risks of pancreatitis and medullary thyroid carcinoma (cancer in the thyroid gland in its medulla, the calcitonin-producing area), which is rare.6 Patients with a personal history of pancreatitis or a personal or family history of medullary thyroid carcinoma must avoid these drugs.6

These drugs also required an FDA approved Medication Guide whenever GLP-1RAs are dispensed. Pharmacy technicians can be very helpful to pharmacists if they check the patient’s bag and make sure that the Medication Guide is in it.

Recent Shortages of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

The sensation of weight loss success for some has caused serious problems for other patients who have diabetes and are struggling to find medication at local pharmacies. Staff in community-based pharmacy practice are well aware of the semaglutide shortages that have occurred in the past year. Pharmacists and technicians should be able to explain the current drug shortages, adverse reactions, and FDA approved or off-label use to patients and other healthcare providers.

“Ozempic face”

As social media and now news media have reported the success of dramatic weight loss, some users bemoan weight loss woes associated with use of GLP-1 agonists. The term, “Ozempic face,” introduced by a dermatologist in New York, describes the typical female patient who has lost a significant amount of weight on semaglutide but now needs (or wants) dermal fillers for her sagging facial structures.10 Patients complain about sagging skin and a gaunt appearance, two problems that follow the loss of facial fat after any harsh weight loss.

Facial fat loss is common when patients lose weight, and when the weight loss is significant, patients will look older. Skin wrinkles and loosens—hallmarks of aging. Similar to weight loss from old-fashioned dieting, fat loss while taking GLP-1 agonists affects the entire body (not just the face). But patients on GLP-1 agonists for cosmetic weight loss fail to understand that they can’t just lose weight where they’d like to lose weight. The facial fat loss is distressing to them.10 Pharmacy teams need to know that “Ozempic face” is a slang term, and GLP-1 agonists don’t specifically target the face.11

Weight Loss Blockbuster or Fad

Over the past two years, celebrities and social media influencers have posted successful weight loss stories while using semaglutide and as a result, catapulted its popularity as a weight loss miracle.12 Questions remain as to how long the weight loss effect will last and if patients will gain the weight back once stopping the treatment. Novo Nordisk, semaglutide’s manufacturer, indicates weight loss can be sustained with long-term use. However, the data collected is limited by a time span of two to three years. Since people who pay out-of-pocket for semaglutide will pay around $1200 per month and some insurance companies may not cover the medication, pharmacists should counsel patients that once the medication is discontinued, weight gain is likely to occur and the weight gain might exceed the original amount lost.12

FDA APPROVED AND OFF-LABEL USE

In December of 2017, the FDA approved semaglutide (Ozempic) for the treatment of diabetes. As significant weight loss was observed, the Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity (STEP) studies produced promising weight loss data.13 As a result, the FDA approved semaglutide for an additional indication, weight loss, in June 2021 under the brand name Wegovy.

Diabetes

In patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), semaglutide is used in combination with diet and exercise to reduce blood sugar levels.14 In patients with T2DM who additionally have established cardiovascular disease, liraglutide and semaglutide are indicated to help lessen the risk of major cardiovascular incidents. Dulaglutide, liraglutide, and semaglutide also have beneficial effects on chronic and diabetic kidney disease.6 Patients who have a history of pancreatitis should avoid any member of the GLP-1RA class and they are not to be used as treatment for patients who have type 1 diabetes.

Dosing semaglutide for the treatment of diabetes requires a period of time for dosage escalation to minimize adverse effects. The FDA has approved both subcutaneous and oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) dosage forms, but only the injectable version is approved for weight loss. Subcutaneously, semaglutide is initially dosed at 0.25 mg once weekly, and after four weeks the patient should increase to 0.5 mg weekly for four weeks. Doses of 1 mg and 2 mg are optional if glycemic control has not been achieved, however the 1 mg dose should also be used for a minimum of four weeks before increasing to the maximum 2 mg strength.6 Dosed on the same day of the week, injections can be dosed at any time of the day with or without regard to meals. Patients sometimes miss or forget their scheduled dosing day. If this occurs, patients should inject the dose within 5 days of the missed dose.6

Patients who have diabetes and currently use metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, or insulin can use semaglutide in combination. However, patients can administer semaglutide and insulin injections at the same time and in the same areas of the body, but not close together; they must never mix them together in the same syringe.14 Hypoglycemic episodes are possible when using a sulfonylurea and/or insulin with semaglutide. Pharmacists therefore should remind patients of the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia when these drugs are used together. Prescribers may need to adjust the dose of insulin and/or a sulfonylurea when starting semaglutide.6

Obesity and Weight Management

Affecting 70% of American adults, obesity and being overweight contribute to a variety of complications and have reduced quality of life.15 Debilitating and expensive disease states associated with obesity include: T2DM, cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea and cancer.13,15 Since obesity has roughly tripled worldwide from 1975 to 2016, investigating the reasons for the rise in prevalence and finding solutions is of utmost importance to prevent and treat obesity.16

The access and ease of inexpensive prepared high caloric foods, limited physical activity, and sedentary life styles are factors that have contributed to the rise of obesity.17 As mentioned, treatment typically has concentrated around the modification of these lifestyle habits.18 Although the weight reduction is usually moderate in magnitude, it is recovered over time (yes, that means that people gain the weight back!).13

Anti-obesity medications have been added to lifestyle modifications. Discouraged by adverse drug reactions, contraindications, cost, and moderate weight loss results with weight that is regained over time, many patients and prescribers are hesitant to consider these treatment options.16

Maintaining weight loss has proved equally difficult due to the regulatory centers in the brain that control appetite. Increased hunger and abnormal satiety signals controlled by neuroendocrine pathways have been discovered in the hypothalamus.16 Researchers have also identified levels of hormones that regulate weight in the hypothalamus. These hormones (leptin, ghrelin, peptide YY, and GIP) play a role in counteracting weight loss after dieting and lead to regain of weight.17, 16

Once semaglutide was approved for the treatment of diabetes, clinical trials focused on weight loss. The STEP trials were phase 3 studies implemented to evaluate the safety and efficacy of semaglutide 2.4 mg subcutaneously once weekly injections for 68 weeks. Patients enrolled in the studies were adults with obesity or overweight, a mean age of 46.2 to 55.3 years, mean BMI of 35.7 to 38.5 kg/m², and were mostly female (mean: 74.1% to 81.0%) for five of the trials.13All studies included lifestyle interventions at varied intensities.13, 18 In one of the larger studies that compared semaglutide with placebo, semaglutide was associated with a 12.4% loss of body weight.15As a result of the ≥ 5% in weight loss exhibited in the studies, the FDA approved semaglutide for chronic weight management.18,15 The approval came in June of 2021, and the manufacturer marketed semaglutide as Wegovy.

The STEP 8 trial compared once-weekly semaglutide to once-daily liraglutide and enrolled 338 adult patients with 126 receiving semaglutide 2.4 mg, and 127 participants receiving liraglutide 3 mg. Participants were overweight or obese, without diabetes, had a mean BMI of 37.5, and most had 0-2 comorbidities with dyslipidemia and hypertension being the most frequent.19, 18 The primary results at 68 weeks reported an estimated mean change in body weight at -15.8% with semaglutide, and -6.8% with liraglutide.19 Based on data from this STEP study, the researchers concluded semaglutide is far superior to liraglutide when used for weight loss and had significantly improved cardiometabolic risk factors.19, 18

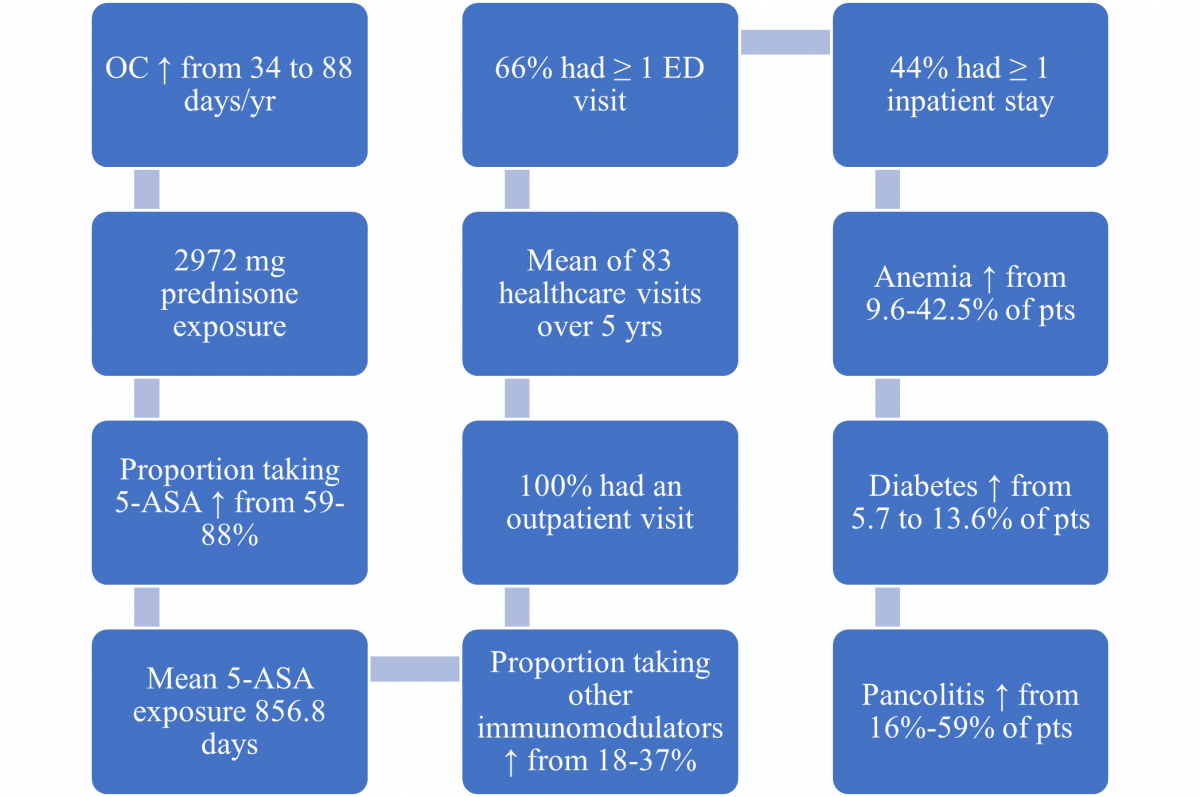

The most frequent adverse side effects reported in the STEP studies were gastrointestinal disorders. Most gastrointestinal side effects were considered mild or moderate in severity and usually were most prominent during the dose titration phase.19 In the STEP 8 study, semaglutide (84.1%) reported a higher occurrence of gastrointestinal events than liraglutide (82.7%).19 Other side effects reported were hypoglycemia, acute pancreatitis, gallbladder disorders that generally resulted in cholelithiasis (gall stones), malignant neoplasms (cancer), change in pulse and injection site reactions.18, 19

SIDEBAR: Alcohol use disorder potential

As patient use of semaglutide has expanded over the past several years, a side effect has emerged that is surprising many clinicians. Patients have reported an abrupt loss in the desire to drink alcohol, almost to the point of repulsion for some patients. GLP-1RAs are known to decrease the desire, enjoyment, and consumption of fatty foods in humans, but observations that patients began to decrease alcohol consumption was unexpected. Although studies to date have observed a reduction of alcohol in rats, mice, and monkeys when receiving GLP-1RAs, reliable researchers avoid extrapolating results from animal studies directly to humans, especially since humans tend to consume more alcohol than animals.20 Since several patients have reported decreased intake of alcohol and data from animal models reflect these results, researchers are starting to investigate GLP-1RAs effect on patients who have alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Existing studies on GLP-1RAs effect on AUD in humans are minimal. A recent study published from Denmark compared the use of a different GLP-1RA, exenatide 2 mg versus placebo in patients with AUD. Researchers were looking to determine if exenatide reduced the amount of heavy drinking days. At the same time, functional MRI brain scans were also completed during the study that focused on areas involved in addiction and reward centers of the brain. Administered once weekly to 127 patients along with cognitive behavior therapy for 26 weeks, exenatide failed to show a decrease in heavy drinking days.21 However, in a subgroup of obese patients (BMI > 30 kg/m2) heavy drinking days and total alcohol intake was reduced.21 Brain scans revealed weakened alcohol cue reactivity and lower dopamine transporter availability for those patients in the exenatide group.21

Ongoing phase two clinical trials are studying the effects of semaglutide on patients with AUD.22 Since semaglutide usage and availability have increased with approved indications for diabetes and obesity, researchers are continuing to investigate this drug class for potential promising new therapies.

Product information

When used for chronic weight management, semaglutide (Wegovy) is approved in addition to a reduced calorie diet and increased physical activity.7, 15 Semaglutide is indicated for patients who meet one of the following criteria: BMI of 30 kg/m² or greater, or patients who have a BMI of 27 kg/m² with at least one comorbid weight related condition (cancer, cardiac disease, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obstructive sleep apnea).7, 15 Available in a prefilled pen that contains one dose, semaglutide is a clear and colorless liquid that can be injected into the upper arm, lower stomach or upper thigh.7 Semaglutide should be stored in the refrigerator between 36°F to 46°F (2°C to 8°C).7 If the pen has been frozen, exposed to light, or heat above 86°F (30°C), the pen should be discarded. The pen remains stable and active for 28 days once removed from refrigeration. Each pen contains the exact dose to be delivered with the needle located inside each pen, therefore each pen should be disposed of in a sharps container.7

Drug shortages, alternatives for therapy

Shortly after marketing Wegovy, the facility hired by Novo Nordisk to fill syringes was cited by the FDA for issues with current good manufacturing processes.23, 24 As a result, deliveries and manufacturing of Wegovy was halted in December of 2021.24 At the same time, staggering demand for the drug was reported by the manufacturer mainly due to news and social media platforms announcing the success of several celebrity weight loss stories. As a result of the Wegovy shortage, prescribers started to write for Ozempic off label in an effort to treat obesity and therefore depleted the supplies of Ozempic.24 At the end of 2022 and early 2023, Novo Nordisk announced that supply issue resolution for Wegovy was on the horizon and that production of the drug was being increased. Due to residual and increasing demand though, some supply issues might continue sporadically but over time distribution centers and pharmacies should receive more drug product in the months ahead.25

CONCLUSION

Probably the first drug to be considered a social media sensation, semaglutide’s entrance into the realm of prescription weight loss treatments has been filled with anticipation, fame, demand, intrigue, and acceptance. Lifestyle management will continue to play a role in losing and maintaining weight loss, with or without a GLP-1RA used in treatment for weight management. Long term use of semaglutide seems to be necessary to maintain a healthy weight but more research is necessary. Gastrointestinal side effects are seen as the most prevalent adverse effect, leading some patients to discontinue the drug. As availability of semaglutide increases due to resolution of the issues that halted production, price, and lack of coverage by insurance plans continues to be problematic for some patients. This is an area where pharmacy technicians can help by looking for coupons or patient assistance programs.

Researchers continue to investigate the various effects seen as a result of usage of semaglutide. Investigators are hopeful of finding new treatments for patients that are struggling with alcohol use disorder and addictive behaviors. GLP-1RAs will continue to be in the headlines for years to come. Pharmacists and technicians hold the golden ticket of information by helping patients and providers understand this unique class of medication’s history, mechanism of action, dosing, side effects, storage requirements, pricing and potential treatments being investigated.

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

Pharmacist Post-test

After completing this continuing education activity, technicians will be able to

• Recall the mechanism of action and dosing schedule of GLP-1 receptor agonists

• Classify adverse reactions most commonly associated with GLP-1 receptor agonists

• Discuss FDA approved and off-label therapeutic uses of GLP-1 receptor agonists

1. What are the GLP-1RAs’ common mechanisms of action in the treatment of diabetes?

A. Stimulate central glucose receptors to secrete insulin, suppress the action of glucagon, and decrease gastric emptying

B. Stimulate the pancreas to secrete insulin, suppress the action of glucagon, and decrease gastric emptying

C. Suppress the pancreas so insulin secretion decreases, increase the action of glucagon, and speed gastric emptying

2. Why do patients who take GLP-1RAs eat less?

A. GLP-1RAs influence specific areas of the hypothalamus that are key to controlling appetite

B. GLP-1RAs influence specific areas of the medulla that are key to controlling appetite

C. GLP-1RAs influence specific areas of the GI tract that are key to controlling appetite

3. Which of the following is a common adverse reaction associated with GLP-1RAs?

A. Vasovagal reaction

B. Blurred vision

C. Gastrointestinal upset

4. Joey is a 44 year-old-man who comes to the pharmacy and says that he is experiencing flatulence and burping ever since he started his GLP-1RA. Which of the following do you

suggest as a way to mitigate this adverse effect?

A. Reschedule the dose to take it right before bedtime

B. Recommend a probiotic with Lactobacillus

C. Avoid high fat foods and alcoholic beverages

5. Which of the following GLP-1RAs are approved by the Food and Drug Administration for weight loss?

A. Semaglutide and liraglutide

B. Dulaglutide and semaglutide

C. Only semaglutide

6. Which of the following would be considered an off-label use of a GLP-1RA?

A. Weight loss in patients with T2DM, used in combination with diet and exercise to reduce blood sugar levels

B. Weight loss in patients who need to lose 10 pounds quickly to fit into Marilyn Monroe’s size 12 dress

C. Weight loss in patients who have a BMI greater than 27 kg/m² with at least one weight-related comorbid condition

Pharmacy Technician Post Test (for viewing only)

Social Media Sensation: Semaglutide

After completing this continuing education activity, technicians will be able to

• Identify the different formulations of GLP-1 receptor agonists

• Classify storage requirements for GLP-1 receptor agonists

• Review GLP-1 receptor agonists indications for use

1. Which of the following GLP-RA is injected once daily?

A. Semaglutide, (Ozempic)

B. Semaglutide, (Wegovy)

C. Liraglutide, (Saxenda)

2. A patient presents a prescription for Wegovy 0.5 mg. Checking the refrigerator, the place for Wegovy is empty. You notice Saxenda is in stock and you have Ozempic 0.5 mg and 1 mg in stock. What is your best response?

A. We have Ozempic 1 mg pens in stock and I can have the pharmacist check and fill today

B. We have Ozempic 0.5 mg in stock but we need a new prescription for Ozempic from your prescriber

C. We have Saxenda in stock, we can have that ready later today

3. Semaglutide should be discarded when exposed to which of the following conditions?

A. Exposed to light or the pen was frozen

B. Refrigeration between 36-46 °F

C. Room temperature for up to 28 days

4. Sharon calls the pharmacy and informs you that she has used her GLP-1RA pen this morning but wants to know how she should dispose of the pen. What is the correct response?

A. At a drug take-back event

B. In a sharps container

C. In the trash

5. Semaglutide is approved for weight loss in patients who have a BMI of what level?

A. BMI between 27-30 kg/m² with two comorbid conditions

B. BMI less than 25 kg/m² who has depression

C. BMI greater than 30 kg/m² alone or 27 kg/m² with one comorbid condition

6. Which of the following would be considered an off-label use of a GLP-1RA?

A. Weight loss in patients with T2DM, used in combination with diet and exercise to reduce blood sugar levels

B. Weight loss in patients who need to lose 10 pounds quickly to fit into Marilyn Monroe’s size 12 dress

C. Weight loss in patients who have a BMI greater than 27 kg/m² with at least one weight-related comorbid condition

References

Full List of References

REFERENCES

- Creutzfeldt, W. The [pre-] history of the incretin concept. Regulatory Peptides. 2005;128:87-91.

- Holst JJ, Gasbjerg LS, Rosenkilde MM. The Role of Incretins on Insulin Function and Glucose Homeostasis. Endocrinology. 2021;162(7). doi:10.1210/endocr/bqab065

- Exendin-4: From lizard to laboratory...and beyond. National Institute on Aging. July 11, 2012. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/exendin-4-lizard-laboratory-and-beyond

- Nauck M, Quast D, Wefers J, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of type 2 diabetes – state-of-the-art. Molecular Metabolism. 2021; 46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101102

- Blakeslee, S. A Protein Tells Eaters To Stop. The New York Times Jan 4, 1996 Section A, Page 1.

- OZEMPIC (semaglutide) injection, for subcutaneous use. Novo Nordisk. October 2022. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://www.ozempic.com/prescribing-information.html

- WEGOVY (semaglutide) injection, for subcutaneous use. Novo Nordisk. June 2021. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/215256s000lbl.pdf

- Wharton S, Davies M, Dicker D, et al. Managing the gastrointestinal side effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists in obesity: recommendations for clinical practice. Postgrad Med. 2022;134(1):14-19. doi:10.1080/00325481.2021.2002616

- Sullivan K, Some people taking weight loss drugs say they're experiencing hair loss. April 22, 2023. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/weight-loss-drugs-and-hair-loss-rcna79798

- Johnson A. ‘Ozempic Face’ Explained: Why It Happens And How To Fix It. February 1, 2023. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/ariannajohnson/2023/02/01/ozempic-face-explained-why-it-happens-and-how-to-fix-it/

- Speckhard Pasque L. Let’s stop using the term “Ozempic face.” February 10, 2023. Accessed March 22, 2023. https://mcpress.mayoclinic.org/women-health/lets-stop-using-the-term-ozempic-face/

- Constantino, A. People taking obesity drugs Ozempic and Wegovy gain weight once they stop medication. March 29, 2023. Accessed April 3, 2023. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/03/29/people-taking-obesity-drugs-ozempic-and-wegovy-gain-weight-once-they-stop-medication.html

- Kushner R, Calanna S, Davies M, et al. Semaglutide 2.4 mg for the treatment of obesity: key elements of the step trials 1 to 5. Obesity. 2020; (6):1050-1061. doi: 10.1002/oby.22794

- Drug Trial Snapshot: Ozempic. US Food & Drug Administration. Published August 20, 2020. Accessed April 12, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/drug-trial-snapshot-ozempic

- FDA Approves New Drug Treatment for Chronic Weight Management, First Since 2014. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Published June 4, 2021. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-drug-treatment-chronic-weight-management-first-2014

- Obesity and overweight. World Health Organization. Published June 9, 2021. Accessed April 18, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Ard J, Fitch A, Fruh S, Herman L. Weight loss and maintenance related to the mechanism of action of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists. Advances in Therapy. 2021;38(6):2821-2839. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01710-0

- Alabduljabbar K, Al-Najim W, le Roux CW. The impact once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg will have on clinical practice: a focus on the STEP trials. Nutrients. 2022;14(11):2217. Published 2022 May 26. Assessed April 20, 2023. doi:10.3390/nu14112217

- Rubino DM, Greenway FL, Khalid U, et al. Effect of Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Daily Liraglutide on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity Without Diabetes: The STEP 8 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA.2022;327(2):138–150. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.23619

- Blum D, Some people on Ozempic lose the desire to drink. Scientists are asking why. February 24, 2023. Accessed May1, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/24/well/eat/ozempic-side-effects-alcohol.html#:~:text=Side%20Effects%3A%20Diabetes%20treatments%20like,can%20also%20take%20a%20toll.

- Klausen MK, Jensen ME, Moller M, et al. Exenatide once weekly for alcohol use disorder investigated in a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. JCI Insight. 2022. 7(19). doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.159863.

- Hendershot C, Semaglutide for alcohol use disorder. NIH Clinical Trials.gov. Indentifier:NCT05520775

- Wegovy® supply update, investor conference call. Novo Nordisk. Dec 2021. Accessed: April 25, 2023. https://www.novonordisk.com/content/dam/nncorp/global/en/investors/pdfs/financial-results/2021/conference-call-supply-update-20Dec2021.pdf

- Goodman B, As the market for new weight loss drugs soars, people with diabetes pay the price. December 28, 2022. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.cnn.com/2022/12/28/health/weight-loss-diabetes-drug-shortages/index.html

- Lovelace Jr B, Supply of weight loss drug Wegovy expected to improve in next few months, company says. February 1, 2023. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/supply-weight-loss-drug-wegovy-expected-improve-months-company-says-rcna68572