Learning Objectives

After completing this continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

- Recognize which patient populations qualify for gene therapy

- Name the different components of gene therapy vectors

- Describe toxicities associated with gene therapies

- Identify gene therapies that are approved/under development in the United States

After completing this continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to

- Recognize patient populations that qualify for gene therapy

- Distinguish types of gene therapies

- Explain the patient experience for different types of gene therapies

- Describe the pros and cons of gene therapy.

Release Date:

Release Date: November 1, 2024

Expiration Date: November 1, 2027

Course Fee

Pharmacists: $7

Pharmacy Technicians: $4

There is no grant funding for this CE activity

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-24-050-H01-P

Pharmacy Technician: 0009-0000-24-050-H01-T

Session Codes

Pharmacist: 24YC50-ABC23

Pharmacy Technician: 24YC50-BCA78

Accreditation Hours

2.0 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-24-050-H01-P/T will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Sandy Casinghino, MS

Retired Senior Principal Scientist

Pfizer, Groton, CT

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Ms. Casinghino has no relationships with ineligible companies.

ABSTRACT

Gene therapy is a relatively new class of medicine that is rapidly evolving, and that brings hope for a cure to patients with genetic diseases. This continuing education activity will introduce learners to the diverse approaches that researchers and clinicians use to correct genes, including in vivo and ex vivo gene therapies. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector-based in vivo gene therapy, one of the most common approaches, is the focus of this learning activity. This activity describes the biology of AAV, vector design and production, toxicities, and FDA-approved AAV-based gene therapies. Finally, a look to the future includes new AAV-based therapies that are in development and a discussion of immune system-related hurdles that must be conquered before AAV-based gene therapy can reach its full potential in maximizing patient efficacy and safety.

CONTENT

Content

INTRODUCTION

Gene therapy is a medical approach to replace missing genes or correct dysfunctional genes in patients with genetic diseases. Gene therapies are best suited for patients who have well-defined, single (monogenic) mutations.1,2 Many are rare diseases for which there are few, if any, treatment options. Therapeutics to correct gene mutations are biologics with the potential to cure a variety of previously incurable diseases such as muscular dystrophy, hemophilia, cystic fibrosis, and some types of blindness. Scientists are also developing gene therapies to stop cancer-causing genes and boost immune responses against tumors.

The term “gene therapy” encompasses multiple broad strategies that can be separated into two general approaches: in vivo (performed inside an organism) and ex vivo (cells that are removed from the organism, genetically modified, and then returned to organism).3 Within these approaches, multiple techniques and delivery systems are currently used or in development:4,5

- Viral vectors (in vivo or ex vivo)

- Non-viral delivery particles (in vivo or ex vivo)

- Gene editing (in vivo or ex vivo)

- Cell engineering (ex vivo only)

The entire field of gene therapy is beyond the scope of this activity. This activity’s focus will be in vivo gene delivery via engineered adeno-associated virus (AAV), with some discussion of gene therapy’s basics and background. This is valuable information for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians as this complex biologic class matures and more gene therapies become available to patients.

BASICS OF GENE THERAPY

Gene Therapy Terminology

People outside of the field may be unfamiliar with many terms used to describe gene therapies. Table 1 defines common terms.

Table 1. Common Terms Used to Describe Gene Therapy6,7,8

| Term | Definition |

| In vivo gene therapy | Administered directly into patients by injection |

| Ex vivo gene therapy | Cells are removed from patients, genetically modified, and re-introduced into patients |

| Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector | Genetically modified virus commonly used to deliver gene therapy in vivo |

| Capsid | Outer icosahedral (20 roughly triangular facets arranged in a spherical or spherical-like manner) protein shell of the virus/viral vector |

| Serotype | Distinct variation between viral capsids within a species based on surface antigens (e.g., AAV serotype 9 [AAV9]) |

| Host | Gene therapy recipient |

| Tropism | A virus’s specificity for a particular host tissue, likely driven by cell-surface receptors on host cells |

| Target tissue | Tissue/organ/cell type intended for genetic correction |

| Gene of interest (GOI)/

transgene |

Gene that needs to be fixed |

| Expression cassette | GOI plus DNA sequences to make it function, including a promoter |

| Inverted terminal repeat (ITR) | DNA sequences that flank the GOI as part of the expression cassette; required for genome replication and packaging; the ITR-flanked transgene forms a circular structure (episome) |

| Episome | Self-contained and self-replicating circular DNA that contains the expression cassette; stays in the cell’s cytoplasm and does not become part of the cell’s chromosomes |

| cap | Gene that encodes the proteins comprising the virus capsid |

| rep | Gene that encodes replicase proteins required for virus replication and packaging |

| Neutralizing antibodies (NAb) | Antibodies that bind to specific areas of viral vector capsids to block uptake by host cells |

| Vector genomes/kilogram of patient body weight (vg/kg) | Common terminology for vector dosing; sometimes referred to as genome copies (gc) per kilogram |

DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid.

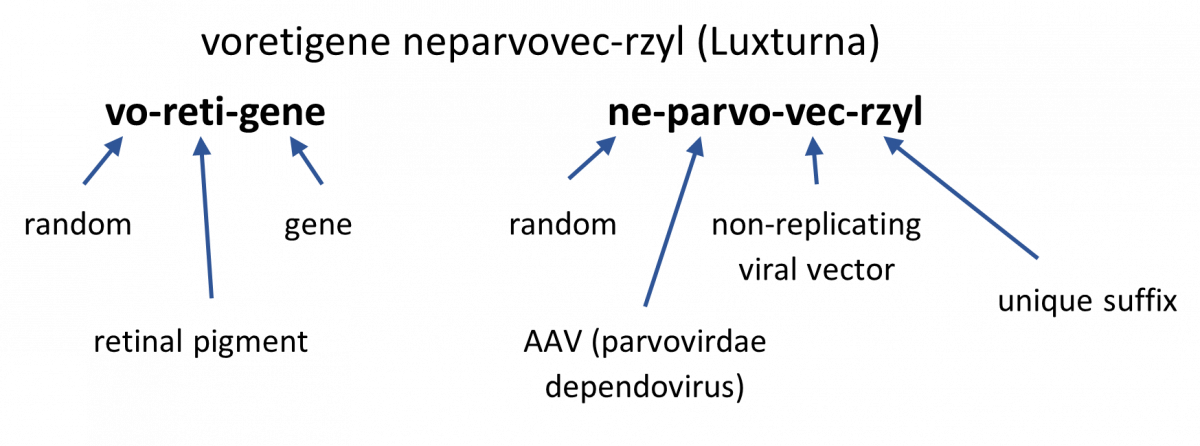

We have used brand drug names preferentially throughout this activity because generic names for gene therapies are complex (See Sidebar).

SIDEBAR: What’s in a Name? How Are Gene Therapies Named?9,10

For in vivo gene therapies, the generic names are composed of two words:

- First word corresponds to the gene component

- Prefix: random element to provide unique identification

- Infix: element to denote the gene’s pharmacologic class (gene’s mechanism of action)

- Suffix: element to indicate “gene”

- Second word corresponds to the vector component

- Prefix: random element to provide unique identification

- Infix: element to denote the viral vector family

- Suffix: element to identify the vector type (non-replicating, replicating, plasmid)

- 4-letter distinguishing suffix: devoid of meaning and attached to the core name with a hyphen

Example:

The Pros and Cons of Gene Therapy

Patients and/or caregivers considering gene therapy should consider several factors11-13:

- Duration of efficacy

- PRO: Potential exists for permanent correction of a disease state. If successful, patients may not need lifelong treatments/medications.

- CON: Gene therapy is relatively new and long-term efficacy data is lacking. If gene expression wanes over time, patients may need redosing (which may be impossible) or alternative treatments.

- Safety

- PRO: Regulatory agencies have approved several products, and safety data is available.

- CON: Complete understanding of adverse effect mechanisms is lacking, and long-term safety information doesn’t exist.

- Cost

- PRO: A curative gene therapy may be more cost-effective than a lifetime of other medications/treatments.

- CON: Available gene therapies are very expensive, $2.9 to $3.5 million for the AAV in vivo therapies approved in 2022 and 2023.

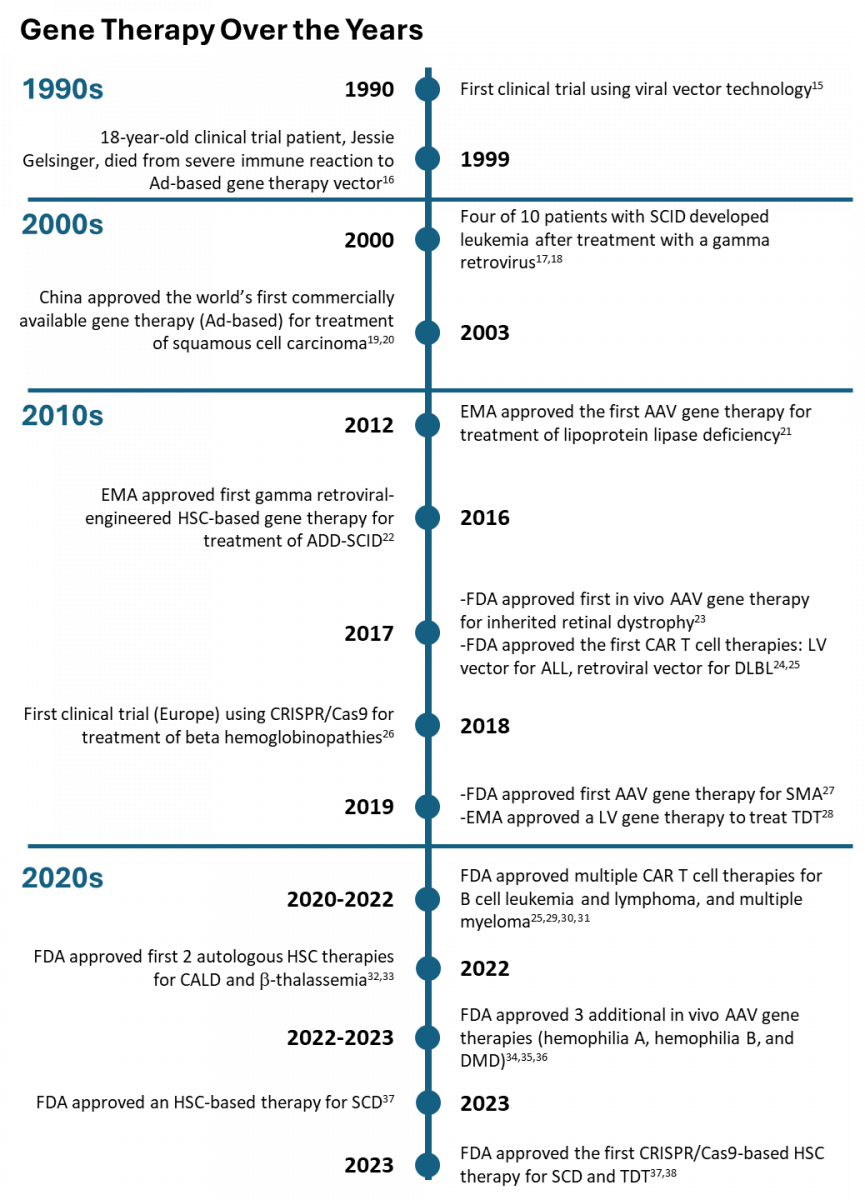

The History of Gene Therapy

Gene therapy is a relatively new field. Clinicians ran the first clinical trial in 1990. Scientists made several advancements in the 1990s and early 2000s, and progress has rapidly accelerated since then.14 (See Sidebar).

ABBREVIATIONS: AAV, adeno-associated virus vector; Ad, adenovirus; ADD, adenosine deaminase deficient; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CALD, cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy; CAR T, chimeric antigen receptor; Cas9, CRISPR-associated protein 9; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HSC, human stem cells; LV, lentivirus; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; SCD, sickle cell disease; SCID, severe combined immunodeficiency disorder; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; TDT, transfusion-dependent thalassemia.

Gene Therapy Systems

Viral Vectors

Prototypical gene therapy is an in vivo approach to curing genetic diseases. It uses a delivery vehicle, such as an engineered virus that encapsulates the gene of interest (GOI) for injection into a patient by various routes, such as intravenous (IV), intraocular, or intrathecal.39 This method takes advantage of a virus’s natural ability to enter mammalian cells efficiently. Once the delivery vehicle enters host cells, the encapsulated gene drives production of the missing or faulty protein. Clinicians use this approach for diseases such as muscular dystrophies, where mutations in the dystrophin gene cause progressive weakness and muscle-wasting, and cystic fibrosis, where mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene impair lung function.

Non-viral Delivery Vehicles

Non-viral delivery vehicles, such as nanoparticles, can also deliver genes or gene editing systems in vivo. These particles use biocompatible materials such as polymers and lipids to carry genes or nucleic acids into cells.3 Researchers can customize a particle’s physiochemical properties to target the intended cell types better and evade immune responses. Non-viral particles are less efficient than viruses at entering cells but may have several other advantages. It’s likely that most patients are immunologically naïve to manufactured particles and lack pre-existing antibodies that may prevent successful uptake by cells. Non-viral particles may also be easier to manufacture and purify, making them more cost-effective to produce than viral vectors.40

Recent gene therapy clinical trials using nanoparticles or lipid nanoparticles include the following41-43:

- Reqorsa: contains a tumor suppressor gene encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle for treatment of several types of lung cancer

- NTLA-2001: contains a gene editing system encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle for treatment of hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (a disease which deposits abnormal protein [amyloid] in organs)

Gene Editing Systems

Gene editing systems, which can be in vivo or ex vivo approaches, can provide precise, targeted gene modifications. Gene editors are engineered nucleases (enzymes) that produce double-stranded breaks at a specific target site. These breaks stimulate the cell’s natural DNA repair mechanisms, resulting in the repair of the break by homology-directed repair or non-homologous end joining. With these systems, target-specific DNA insertions, deletions, modifications, or replacements are all possible.3,44

Many gene editing tools exist, including3,44

- clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) Cas-associated nucleases

- transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs)

- zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs)

- meganucleases (MNs)

Gene editing ex vivo systems are a fast-growing area with many programs in development.41 In vivo gene editing is rife with challenges, especially those concerning delivery to the intended cells. Gene editing systems are an evolving cutting-edge platform reviewed in much more detail elsewhere.3,44,45

Ex Vivo Gene Therapy

In ex vivo gene therapy, medical and/or laboratory personnel remove a patient’s cells from the body, genetically modify them (using viral vectors, non-viral delivery particles, or gene editing systems), and then re-introduce them into the patient. Alternatives to the use of a patient’s cells include genetically modified cell lines or cells from another donor. The use of autologous (patients’ own) cells avoids the need to find an immuno-compatible donor. Examples of systems include chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and engineered hematopoietic stem cells (HSC). CAR T cells are T lymphocytes that are modified to recognize tumor antigens, such as the B lymphocyte antigen Cluster of Differentiation-19 (CD-19) and B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA). Once genetically modified, the CAR T cells bind to cells expressing the tumor antigen and subsequently kill them. HSC have the ability for self-renewal and to differentiate into multiple cell lineages, therefore engineering them to correct genetic flaws such as enzyme deficiencies and hemoglobinopathies (inherited disorders affecting hemoglobin, the molecule that transports oxygen in the blood) makes them a promising approach.

Several products have received regulatory approval in the United States (U.S.)46:

- Autologous CAR T cells47-50

- CD19-directed autologous T cell immunotherapies for the treatment of various types of B cell lymphomas include the following:

- Yescarta (axicabtagene ciloleucel) – approved 2017

- Kymriah (tisagenlecleucel) – approved 2017

- Tecartus (brexucabtagene autoleucel) – approved 2020

- Breyanzi (lisocabtagene maraleucel) – approved 2021

- BCMA-directed autologous T cell immunotherapies for treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma include the following51,52:

- Abecma (idecabtagene vicleucel) – approved 2021

- Carvykti (ciltacabtagene autoleucel) – approved 2022

- CD19-directed autologous T cell immunotherapies for the treatment of various types of B cell lymphomas include the following:

- Autologous HSC-based gene therapies include the following53-56:

- Skysona (elivaldogene autotemcel) – slows neurological dysfunction in cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy by inducing synthesis of adrenoleukodystrophy protein – approved 2022

- Zynteglo (betibeglogene autotemcel) – corrects β-thalassemia by adding functional copies of a modified β-globin gene into the patient’s HSC – approved 2022

- Casgevy (exagamglogene autotemcel) – first FDA-approved CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing therapeutic; corrects sickle cell disease (SCD) and transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia by adding functional copies of a modified β-globin gene into the patient’s HSC – approved 2023

- Lyfgenia (lovotibeglogene autotemcel) – corrects SCD by adding functional copies of a modified β-globin gene into the patient’s HSC – approved 2023

CAR T cell gene therapy is an effective treatment for several types of cancers but comes with many challenges to patients, medical professionals, and pharmacy personnel. Product manufacturing, administration, and adverse effect mitigation are more complex than for many other treatment types. Medical, laboratory, and/or pharmacy personal carry out the following key steps at specialized medical centers47-50:

- Collect the patient’s white blood cells (leukapheresis)

- Manufacture the CAR T cells in a laboratory with a typical time frame of two to four weeks

- Patients may need to travel to and remain near the center while they wait for the cells

- If the process fails, then personnel must repeat the cell collection and CAR T cell manufacturing

- Administer chemotherapy to deplete the patient’s lymphocytes, two to 14 days prior to CAR T cell infusion, which makes room for the CAR T cells

- Administer the CAR T cells to the patient by slow infusion to minimize infusion-related adverse reactions

- Monitor the patient for at least four weeks, likely requiring the patient to stay at or near the treatment center

This therapy class carries Boxed Warnings:

- CD-19 directed therapies47-50,57

- Cytokine release syndrome (CRS): over-activation of the immune system with release of large amounts of cytokines (immune system proteins); this is a common, potentially life-threatening adverse event

- Neurotoxicity: the mechanism by which this occurs is not well understood, but it is common and can be life-threatening

- BCMA-directed therapies53,54

- CRS and neurotoxicity as listed for CD-19 directed therapies

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis/macrophage activation syndrome: a hyperinflammatory immune response that can be life-threatening

- Prolonged cytopenia (low numbers of blood cells) with bleeding and infection; can be life-threatening

Ex vivo gene therapy with autologous HSC is also a complex process with multiple challenges and toxicities.53,54 For these therapies, medical personnel pretreat patients with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor to increase production and release of HSCs from bone marrow. Laboratory staff then collect and purify HSC from the patient’s blood. Staff may need to collect cells more than once to amass the required number of cells or in cases where manufacturing fails. Laboratory staff genetically modify the patient’s HSCs, typically with a lentiviral vector, to express the GOI. The cell manufacturing process can take up to three months. The modified cells require cryopreservation and liquid nitrogen storage conditions, adding to the process’s complexity.

When the cells are ready, medical personnel administer lymphocyte-depleting chemotherapy to the patient to remove HSCs that are making the faulty protein and to make room in the bone marrow for the genetically modified HSCs. Next, medical personnel infuse the thawed HSCs to the patient intravenously. After infusion, patients may need to stay at the medical center for several months for recovery and monitoring.

The prescribing information lists toxicities including prolonged cytopenias, serious infections, and an increased risk for lentiviral vector-mediated oncogenesis (development of a new cancer). It recommends patient monitoring for 15 years to life for hematologic malignancies. Skysona and Lyfgenia have Boxed Warnings for hematologic malignancy.53,56

The overview above describes how the field of gene therapy is broad and encompasses multiple approaches. New and evolving approaches include non-viral delivery, gene editing, and ex vivo cell engineering; they have recently started to become available to patients. This is an exciting and hopeful time for patients with genetically-linked diseases, and it is likely that many more effective and approved therapies will be available soon.

AAV-BASED IN VIVO GENE THERAPY

Although researchers are developing viral vectors based on many types of viruses (e.g., adenovirus, gamma retrovirus, herpes simplex virus, lentivirus) adeno-associated virus (AAV) has emerged as the leading viral vector for in vivo gene therapy with five current regulatory approvals in the U.S. and many more programs under development.41,46 Its favorable characteristics include not causing human disease, inability to replicate in the host without a helper virus, and ability to elicit a low host immune response relative to many other viruses. Since the expression cassette is typically maintained on an episome, scientists expect AAV-based vectors to have a low frequency of integration into the host genome, conferring a minimal risk of cancer.58 In addition, at least one serotype of AAV (AAV9) can cross the blood-brain barrier making AAV a suitable choice for neurologic diseases without invasive local administration of the vectors into the brain. Researchers find AAV-based vectors to be attractive, versatile tools with suitable properties and utility for a wide variety of diseases.

AAV Biology

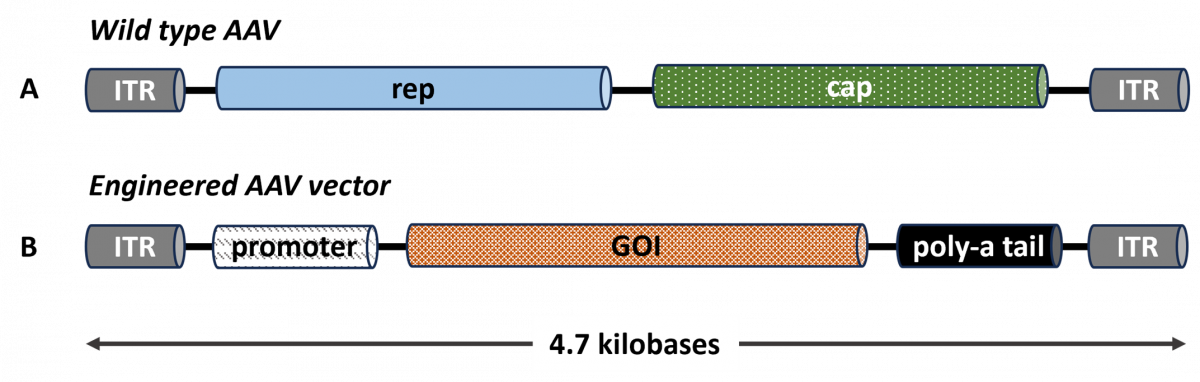

Naturally occurring AAVs are small, non-enveloped viruses that belong to the Parvovirus family. They have a linear single-stranded DNA genome of approximately 4.7 kilobases, including rep and cap genes that encode for replication and capsid proteins, respectively.3 Figure 1A illustrates the genomic structure of a wild type (naturally occurring) AAV.

In engineered AAVs used for gene therapy, developers remove the rep and cap genes and replace them with an expression cassette, as illustrated in Figure 1B. The expression cassette contains the GOI, regulatory elements (promoter/enhancer), and poly-adenosine tail (to stabilize the messenger RNA and facilitate translation into protein) flanked by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs; required for genome replication and packaging). The expression cassette replaces approximately 96% of the native genome.3

Figure 1. Genomic Structure of Wild Type AAV and Engineered AAV Vector

cap, capsid gene; GOI, gene of interest; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; rep, replicase gene.

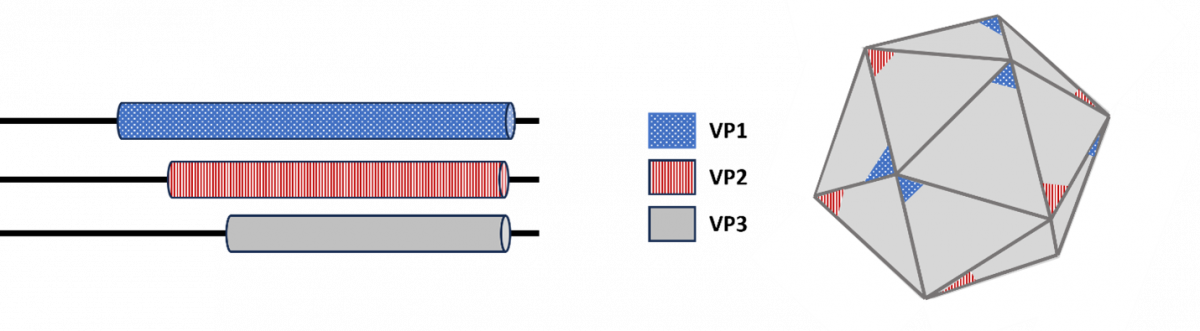

AAV capsids in both the wild type AAV and engineered AAV vectors are composed of three viral proteins (VPs) named VP1, VP2, and VP3. Sixty molecules of these proteins, estimated to exist in a 1:1:10 ratio (VP1:VP2:VP3), assemble into each icosahedral capsid (Figure 2). The VP sequences overlap, with VP1 being 137 amino acids longer than VP2, which is 57 amino acids longer than VP3. Differences in VP3 sequences distinguish one AAV serotype from another.59

Figure 2. Protein Structure of the AAV Capsid

VP, viral protein.

AAV exists as at least 11 natural serotypes, which share about 51% to 99% sequence identity in their VP3 protein.60,61 Sequence comparisons between different AAV serotypes identified nine variable regions situated on the capsid surface. The specific amino acid sequences of these regions impact AAV binding to host cell receptors, thus determining cell- and tissue-specific tropism (affinity for a specific tissue or cell type). These variable sequences also function as binding sites (epitopes) for AAV-specific antibodies, thus influencing host immune responses.62

An AAV serotype can be tropic to multiple cell types and tissues, and multiple serotypes can be tropic to the same cells/tissues. Researchers isolate serotypes from non-human primates and develop synthetic serotypes using protein engineering to alter tropisms and/or evade pre-existing AAV-specific antibodies.1

PAUSE AND PONDER: If your child had a life-shortening genetic disorder and a new AAV9-based therapy became available, how would you feel if your child had a high anti-AAV9 neutralizing antibody titer that excluded them from clinical trials or treatment?

Neutralizing antibodies (NAbs) are naturally occurring antibodies that bind to AAV surface epitopes and block uptake into target cells. NAb binding to the AAV capsid can induce rapid clearance of the gene therapy by the patient’s immune system. Clinical personnel must screen patients for pre-existing Nabs. Trial protocols and prescribing instructions often exclude patients with NAbs specific for the gene therapy’s serotype.

Older children and adults tend to have a high prevalence of pre-existing antibodies against commonly circulating (wild type) AAV serotypes because of previous exposure to these viruses over the course of their lives. For example, studies showed that approximately 40% of humans have NAbs to AAV serotypes 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9.63 Between 6% and 95% of individuals with hemophilia A and B have AAV-specific antibodies based on AAV serotype and assay used.64 In addition, due to the high degree of conservation of capsid protein amino acid sequences, pre-existing antibodies to one serotype may cross-react with other serotypes, further limiting the availability of a therapy for a patient. Patients without NAbs prior to gene therapy will develop high titers of NAbs following vector administration, rendering them ineligible for additional rounds of gene therapy with the same vector or a cross-reactive serotype.1,63-65

Vector Design

To create a vector for a particular disease, drug developers try to target an AAV vector to the specific cell or tissue type where gene correction is needed. The capsid serotype choice significantly influences this decision.

AAV2, AAV5, AAV6, AAV8, and AAV9 account for a majority of the ongoing AAV gene therapy clinical trials.60,66 Commonly, AAV2 or AAV8 is the choice for ocular therapies; AAV2, AAV8, AAV5, and AAV9 are best for liver targeting; and AAV2 and AAV9 are preferred targeting muscle or the central nervous system. Some researchers are also using AAV serotypes isolated from rhesus monkeys, such as rh74.60,67 As discussed, AAV9 can cross the blood-brain barrier, allowing IV administration of this serotype to target brain tissue while avoiding invasive intrathecal injections.60,68 Therefore, AAV9 is a popular vector to treat many diseases affecting the nervous system.

Developers derive the capsids of AAV vectors either from natural AAV viruses or by engineering capsids through rational design, directed evolution, or computer-guided strategies. The impetus to develop AAV vectors with capsids from less common AAV serotypes or novel engineered AAV capsids serves to improve or modify tissue targeting and circumvent immune recognition.69

Considerations for vector design include61,62

- Choosing the best AAV serotype to target the intended cell type or tissue, using the desired route of administration

- Potential for tissue-specific promoters (e.g., targeting the muscle for muscular dystrophy or the liver for hemophilia) rather than constitutive promoters (that will drive gene expression in a wide range of tissues and perhaps result in off-target toxicity)

- Whether an enhancer is needed to boost expression in the target tissue to achieve desired therapeutic effect

- Modifying capsid epitopes to reduce recognition/response from the host immune system

Vector Production and Purification

Once developers choose the best capsid serotype and design the vector, they proceed to the manufacturing step. Gene therapies are complex biologics, and manufacturing and purification are of utmost importance for efficacy, safety, and product stability. Regulatory agencies require good manufacturing practice compliance.70

Scientists commonly use mammalian cell lines to propagate engineered AAV vectors and then purify the vectors from cell lysates. Rigorous purification is essential. As the science of gene therapy matures, drug developers continuously improve purification methods. Contaminants from the engineered AAV cultivation process are a potential source of toxicity and can induce unwanted immune responses. Release testing of the final product in the U.S. must comply with a series of FDA-established requirements and predetermined specifications to determine product safety, purity, concentration, identity, potency, and stability.71 Characterization of the final product includes a determination of the viral genome (vg) titer, infectious titer (potency), product identity (AAV capsid and genome), and therapeutic gene identity (expression/activity).72

Gene therapy developers follow these steps to manufacture AAV-based therapies73-75:

- Use conventional recombinant DNA technology in bacterial systems to produce the plasmids

- Use mammalian cell lines, such as human embryonic kidney 293 cells, or insect cell lines, such as the baculovirus/insect cell system, to produce the vectors

- Transfect (introduce genetic material into a cell) three plasmids into the cell line

- a recombinant AAV plasmid containing the expression cassette (see Figure 1b)

- an adenovirus-based helper plasmid supplying genes needed for virus replication

- a plasmid containing the essential rep and cap genes needed for virus replication and capsid formation

- Collect produced vectors from the cells and purify them. Complex purification processes require multiple methods that may be specific for each individual contaminant. Rigorous purification minimizes patient risk (see Sidebar). Examples of purification process steps (and techniques used) include the following:

- Cells lysis to release the viral particles (detergent, mechanical stress, hypertonic shock, freeze-thawing)

- Removal of nucleic acids (nuclease treatment), cell fragments and proteins, cell culture contaminants (centrifugation, filtration, chromatography)

- Separation of full vector particles from empty particles (cesium chloride gradient ultracentrifugation or chromatography)

- Formulate vectors after purification for administration to the patient. Formulation optimization prior to manufacture is not trivial. Some considerations are:73-75

- Formulation chemical composition must be optimized for intended route of administration

- Formulation must be sterile and have low endotoxin concentration

- Formulation must minimize product degradation to avoid aggregation and loss of efficacy due to product instability

SIDEBAR: Patient Safety: The Importance of Purification of AAV69,74

- Non-vector sequences (including plasmid DNA, helper virus DNA, and DNA from the cell line used to produce the vector) can unintentionally be packaged into the capsids. AAV vector genomes can recombine with non-vector DNA, resulting in AAV vectors that contain chimeric (mixtures of DNA from different sources) sequences. The behavior of these unintended sequences is unpredictable in patients.

- Capsids containing the complete intended therapeutic gene, partial sequences, unintended chimeric sequences, or no genetic sequence material at all (empty capsids) are all possible outcomes of vector manufacturing. Administering a mixture of different forms of the therapeutic to patients may result in a partial effective dose, thus lowering potency and necessitating administration of higher overall numbers of AAV particles to achieve efficacy. The higher the number of AAV particles, the higher the risk of toxicities and immune system activation.

Toxicities/Adverse Events

Although AAV gene therapy is generally considered safe, multiple treatment-emergent serious adverse events have occurred following gene therapy administration to patients. These include severe hepatoxicity and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Other potential toxicities and identified risks include myocarditis, neurotoxicity (dorsal root ganglion [DRG] degeneration), oncogenicity, and immunotoxicity.69

In general, AAV vectors administered IV first travel to the liver. Liver enzyme increases denoting liver damage commonly occur and corticosteroid treatment is often effective. On occasion, acute serious liver injury, liver failure, and death have occurred. Although the mechanism is not completely understood, more severe liver injury appears to correlate with higher vector doses. Severe liver injury following AAV vector administration for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and X-linked myotubular myopathy genetic diseases has occurred.69,76

TMA is a pathological condition characterized by formation of thrombi (clots) in small blood vessels, following endothelial cell injury. TMA’s clinical presentation often includes complement activation, cytokine release, thrombocytopenia (decreased platelets), and kidney injury/failure. Several cases of TMA have been reported in patients or clinical trial participants following AAV gene therapy for SMA and Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Treatments for affected patients included hemodialysis, platelet transfusion, and the complement inhibitor eculizumab. As with severe liver injury, TMA development appears to be related to high vector doses.77,78

Several patients in DMD clinical trials have developed myocarditis, which was fatal in one patient. A hypothesis is that pre-existing inflammation in DMD patients’ muscles, including heart muscle, worsened upon local expression of dystrophin. Steroid treatment successfully resolved myocarditis in some cases.79

DRG degeneration/toxicity is an identified potential risk of AAV gene therapy. DRGs are collections of sensory neurons that relay impulses from the periphery to the central nervous system. Researchers have observed AAV vector-induced DRG toxicity mainly in non-clinical studies with pigs and non-human primates. Direct administration of AAV into cerebral spinal fluid and high vector doses were contributing factors. Pathology studies have detected DRG degeneration in autopsy samples from humans who received AAV gene therapy. Scientists do not completely understand DRG toxicity’s underlying mechanisms in animals or the significance of clinical translation to humans.80

Oncogenicity due to insertional mutagenesis (introducing foreign DNA into a person’s genome) is a potential risk of gene therapy. Studies in mice that received AAV vectors revealed integration events and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatocyte clonal expansion occurred in dogs following AAV vector administration although tumors were not found. AAV vector genome integration into chromosomes has been detected in humans, but so far AAV-associated oncogenesis has not been reported.58 Due to the potential risk, regulators expect long-term monitoring after vector administration.69,81

Although immune responses to wild type AAV are low relative to other viruses, AAV can engage all arms of the immune system and can do so robustly especially when high vector doses are administered. The immune response to AAV gene therapy is complex, and poorly understood, and can contribute to loss of efficacy and adverse effects. Local (rather than systemic) dosing, use of tissue specific promoters, and increasing the vector’s potency (increasing promoter strength/achieving higher levels of expression per AAV particle) may effectively minimize toxicity.65,76,82,83

Immune responses to AAV gene therapy include the following65,66,79,82:

- Innate immune responses: may lead to cytokine induction and/or activation of the complement cascade (e.g., toll-like receptor recognition and signaling in response to capsid proteins and nucleic acids)

- Humoral responses: antibody binding to AAV capsid may activate complement and immune cells and remove the vector from circulation before it can reach its target tissue. After gene therapy administration, the body generates new antibodies that can be specific for a capsid or transgene product.

- Cellular immune responses: may lead to inflammation and elimination of the cells producing the disease-correcting protein (e.g., activation/expansion of capsid- or transgene-product-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes)

APPROVED IN VIVO GENE THERAPIES

As of December, 2023, the FDA approved eight in vivo gene therapies, five of which are AAV based.46

Non-AAV-Based Therapies

Three of the FDA-approved in vivo gene therapies are non-AAV based; they are adenovirus (Ad)-based or herpes simplex virus (HSV)-based. None are systemically administered, but instead are administered locally to the skin or bladder.

Vyjuvek (beremagene geperpavec-svdt) is a live, replication deficient HSV type 1 (HSV-1) vector genetically modified to express human type VII collagen. Vyjuvek is indicated for wound treatment in patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa with mutation(s) in the collagen type VII alpha 1 chain gene. Topical application to wounds induces production of the mature form of type VII collagen leading to wound healing.84

Adstiladrin (nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg) is a non-replicating adenoviral serotype 5 vector genetically modified to produce human interferon α-2b (IFNα-2b). Adstiladrin is indicated for patients with high-risk Bacillus Calmette-Guérin-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer with carcinoma in situ with or without papillary tumors. Intravesical (within the bladder) instillation results in local expression of IFNα-2b protein that is anticipated to have anti-tumor effects.85

Imlygic (talimogene laherparepvec) is a live, attenuated HSV vector genetically modified to replicate within tumors and to produce the immune stimulatory protein granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). Imylgic is indicated for local treatment, by intralesional injection of unresectable cutaneous, subcutaneous, and nodal lesions in patients with melanoma recurrent after initial surgery. Imylgic causes tumor lysis followed by release of tumor-derived antigens, which together with virally derived GM-CSF may promote an antitumor immune response. However, the exact mechanism of action is unknown.86

AAV-Based Therapies

Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl) is a genetically modified non-replicating AAV2 expressing the human retinoid isomerohydrolase (RPE65) gene approved in 2017. It’s used to treat patients with confirmed biallelic RPE65 mutation-associated retinal dystrophy, a condition causing progressive retinal degeneration and dysfunction, which can lead to vision loss and blindness over time. Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells produce RPE65. Mutations in this gene result in vision impairment, so Luxturna aims to correct these mutations. A clinician administers 1.5 x 1011 vg of Luxturna subretinally (directly into the space beneath the retina) to each eye on separate days, at least six days apart. Patients typically take systemic oral corticosteroids starting three days before its administration and continuing with a tapering dose for 10 days. Preparation of Luxturna for administration is complex and includes thawing, dilution, and preparation of syringes for injection. Warnings and precautions include endophthalmitis (infection/inflammation of the inner structures of the eye), permanent decline in visual acuity, retinal abnormalities, increased ocular pressure, intraocular air bubble expansion, and cataracts. Immune responses to Luxturna were mild in clinical trials, perhaps due to corticosteroid administration.23

Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi) is a genetically modified non-replicating AAV9 expressing the human survival motor neuron (SMN) protein. The FDA approved it in 2019 for treatment of patients younger than 2 years of age with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) with bi-allelic mutations in the SMN1 gene. SMN protein is key for muscle development and movement and Zolgensma aims to correct these mutations to treat the disease. After Zolgensma is thawed, a clinician administers 1.1 × 1014 vg/kg of Zolgensma intravenously by slow infusion. Patients typically take systemic corticosteroids starting one day before Zolgensma administration and continuing for a total of 30 days. Serious adverse effects described in the Boxed Warning include acute liver injury and failure with fatal outcomes. Other warnings and precautions include systemic immune response, thrombocytopenia, TMA, and elevated troponin (a protein involved in muscle contraction).87

Hemgenix (etranacogene dezaparvovec-drlb) is a genetically modified non-replicating AAV5 expressing human coagulation Factor IX (Padua variant), under control of a liver-specific promoter. Approved in 2022, it is employed to treat male patients with hemophilia B (congenital Factor IX deficiency). The Padua variant has an 8-fold higher specific activity relative to wild type Factor IX, and Hemgenix would ideally correct the disease by providing circulating Factor IX activity. Clinicians administer 2.0 × 1013 gc/kg of Hemgenix by slow intravenous infusion. Hemgenix is a refrigerated suspension that requires dilution into normal saline. The prescribing information recommends corticosteroids, not prophylactically, but only if the liver enzyme aspartate aminotransferase (AST) increases to twice the patient’s baseline value. Warnings and precautions include infusion reactions (including anaphylaxis), hepatotoxicity, and hepatocellular carcinogenicity (theoretical risk if vector DNA integrates into the host cell genome).88

Elevidys (delandistrogene moxeparvovec-rokl) is a genetically modified non-replicating AAVrh74 (originally isolated from rhesus monkeys) expressing human micro-dystrophin. The FDA approved it in 2023 for treatment of ambulatory 4- to 5-year-old patients with DMD with a confirmed mutation in the dystrophin gene. The vector’s promoter/enhancer drives transgene expression predominantly in skeletal and cardiac muscle. The dystrophin protein’s micro version consists of selected domains of dystrophin that confer function to muscle cells. After Elevidys is thawed, clinicians administer 1.33 × 1014 vg/kg by intravenous infusion using a syringe infusion pump. The prescribing information recommends prophylactic corticosteroids following a complex administration and tapering schedule, which is further complicated in patients with DMD already on a corticosteroid regimen. Warnings and precautions include acute serious liver injury, immune-mediated myositis, and myocarditis.89

Roctavian (valoctocogene roxaparvovec-rvox) is a genetically modified non-replicating AAV5 expressing the B-domain-deleted form of human coagulation Factor VIII (the smallest active form of Factor VIII) under control of a liver-specific promoter. Approved in 2023 for treatment of male patients with severe hemophilia A, clinicians administer Roctavian after thawing at 6.0 × 1013 vg/kg by intravenous infusion using a syringe infusion pump. The prescribing information recommends corticosteroids, not prophylactically, but only if liver enzymes increase to 1.5 times the patient’s baseline or to above the upper limit of normal. Warnings and precautions include infusion reactions (including anaphylaxis), hepatotoxicity, and thromboembolic events.90

PAUSE AND PONDER: The prescribing information for Hemgenix and Roctavian do not recommend these gene therapies for women. Why?

A LOOK TO THE FUTURE

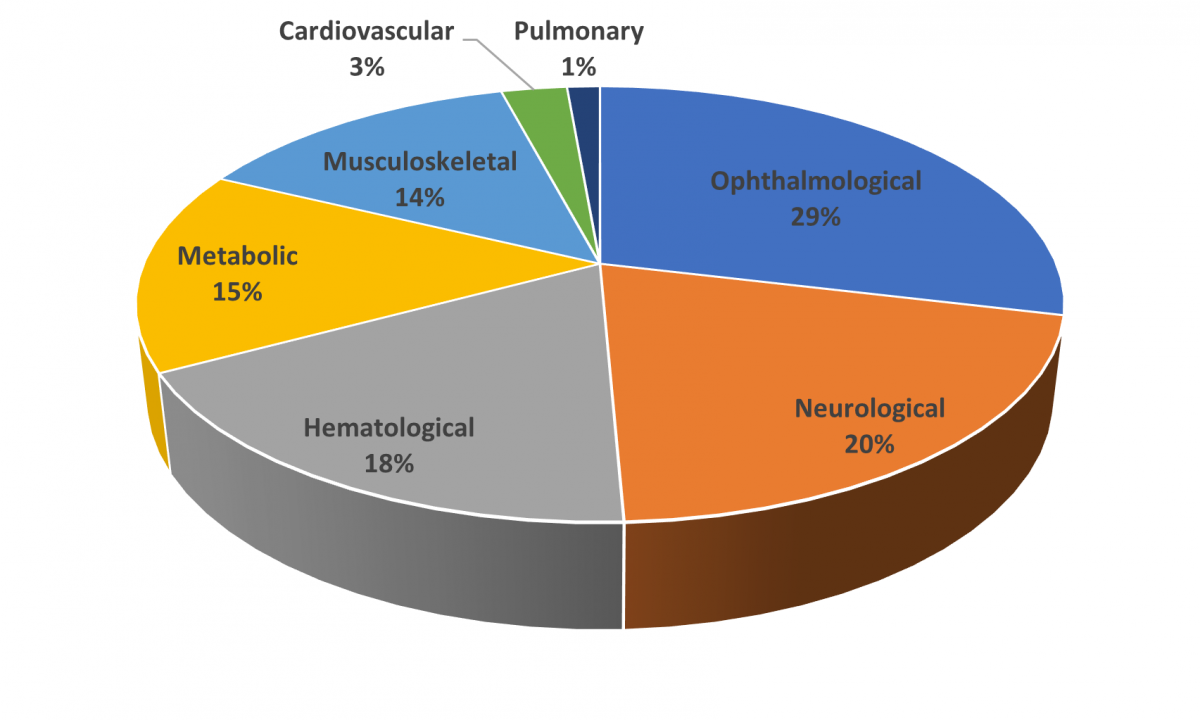

As discussed above, the FDA has approved five AAV-based gene therapies, Figure 3 illustrates disease indications being studied in AAV-based clinical trials including 90 ongoing, interventional studies.41

Figure 3. AAV-based gene therapy clinical trials for different disease indications as a percentage of all AAV-based clinical trials for therapies not yet approved for marketing41

The percentages of each disease indication were calculated based on the total of current AAV-based interventional clinical trials. Clinical trials were identified using the search terms gene therapy and adeno-associated (for condition/disease) and interventional (study type). Trials designated as recruiting, active – not yet recruiting, enrolling by invitation, and completed were included in the analysis (n = 73). Trials designated as terminated, suspended, or unknown status were not included. Data are current as of April 12, 2024.

Ophthalmology and neurology represent the highest percentage of forthcoming therapies. Within the ophthalmology category, multiple trials are underway for achromatopsia (color blindness), amaurosis (complete vision loss without visible eye damage; typically, an optic nerve disease), and retinitis pigmentosa (progressive vision loss due to retina deterioration), among others. The neurological disease category includes trials for Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and others. Hematological and musculoskeletal clinical trials are highly focused on hemophilia and muscular dystrophies, respectively. The metabolic disease category is diverse containing a few trials each for numerous genetic diseases.41

Controlling the immune response to AAV vectors is one of the biggest hurdles for future therapeutics. The human immune system is complex and very efficient. Often, it has a back-up plan in case an organism escapes the first round of attack and usually a back-up plan for the back-up plan. It becomes impossible for an AAV vector (a virus in sheep’s clothing) to go unnoticed, especially when the doses are greater than 1 trillion vg/kg of body weight. Thus, a patient’s immune system will go into action starting shortly after receiving gene therapy and mount a multi-pronged attack.

New and improved strategies to control immune responses will greatly benefit patients. Researchers are diligently pursuing strategies (Table 2) that target the vector itself or immune system components.91-93 Success will probably use a combinations of strategies.

Table 2. Strategies to Control or Circumvent Immune Responses91-94

| Strategy | Rationale | Potential Advantages | Potential Disadvantages |

| AAV capsid engineering

|

Remove or alter NAb-binding epitopes | · Allow dosing with pre-existing NAb

· Allow redosing |

· Complex, expensive, lengthy process

· May alter tropism to target tissue · May require patient screening to determine what epitopes to modify |

| Direct administration to appropriate tissue | Minimizing systemic exposure may minimize immune response | · Reduced toxicity after gene therapy administration | · Not possible for all indications |

| Plasmapheresis

|

Reduce amount of all immunoglobulins in a patient | · Allow dosing with pre-existing Nab

· Allow redosing |

· Invasive procedure

· Not specific for capsid antibodies · May increase infection risk due to reduced circulating antibody |

| Capsid decoys

|

Pretreat patient with empty capsid to ‘absorb’ capsid-specific antibodies | · Allow dosing with pre-existing Nab

· Allow redosing |

· Depending on clearance time for empty capsid-NAb complexes, may increase the total capsid burden and enhance immune response |

| IdeS | Degrades all IgG | · Allow dosing with pre-existing Nab

· Allow redosing · Good safety profile in transplant patients |

· Patient may have pre-existing antibodies to IdeS that could induce an immune response

· Patient may develop antibodies to IdeS, so may not be able to be used more than once · Not specific for anti-AAV IgG · Increased infection risk due to reduced circulating IgG |

| Immunosuppression | Overall or cell type-specific suppression of the immune response | · Reduced toxicity after gene therapy administration | · Can have adverse effects, especially if used long term

· Increased infection risk |

AAV, adeno-associated virus; IdeS, immunoglobulin G-degrading enzymes of Streptococcus pyogenes; IgG, immunoglobulin type G; NAb, neutralizing antibody.

Perfection of technologies to remove pre-existing NAbs would allow many more patients to be eligible for gene therapies. Curbing antibody production in the days following the gene therapy may boost efficacy, reduce toxicity, and allow patients to remain eligible for more than one round of AAV gene therapy if needed. Methods to control T cell-mediated responses would prevent destruction of the cells producing the transgene product, increasing the persistence of the curative gene expression.

Early clinical studies took a reactive approach to immune responses to AAV; they used medications such as corticosteroids following observation of increases in liver enzymes or signs of inflammation. More recently, efforts to identify drugs and combinations of drugs that will suppress the immune response prophylactically have accelerated91,93:

- Corticosteroids (e.g., methylprednisolone): general anti-inflammatory

- Tacrolimus: inhibits T cell proliferation and differentiation

- Rituximab: depletes B cells to block antibody production

- Rapamycin (sirolimus): disrupts cytokine signaling resulting in inhibition of B cell and T cell activation

- Mycophenolate mofetil: inhibits B cell and T cell proliferation

- Eculizumab: complement inhibitor

- Hydroxychloroquine: inhibits toll-like receptor-9-mediated responses to viral DNA an antigen presentation

Researchers must investigate other key variables: the timing of immunosuppression initiation and the requisite treatment duration.

Many clinical trials have employed corticosteroids, but corticosteroids alone are insufficient to control immune responses. Regulators have approved the immunosuppressants listed above for indications other than gene therapy, and their safety profiles are known, making them logical choices to investigate for gene therapy indications. Future work must maximize safety and efficacy of AAV gene therapy while balancing adverse effects of the immunosuppressive regimens.93

SUMMARY

Gene therapy is a relatively new, complex, and evolving field in medicine that offers hope to patients with previously incurable genetic diseases. The information presented here is intended to introduce a topic that pharmacists and pharmacy technicians may not have been previously exposed to, and perhaps inspire them to read more.

Download PDF

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

GENES AS MEDICINES: GENE THERAPY

Pharmacist Posttest

Learning Objectives

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

• Recognize which patient populations qualify for gene therapy

• Name the different components of gene therapy vectors

• Describe toxicities associated with gene therapies

• Identify gene therapies that are approved/under development in the United States

1. Which of the following patients would qualify for an AAV9-based gene therapy?

A. A patient with a monogenic disease who has neutralizing antibodies to AAV9

B. A patient with a monogenic disease without neutralizing antibodies to AAV9

C. A patient with an undefined genetic disease without neutralizing antibodies to AAV9

2. Which of the following is an in vivo approach to gene therapy?

A. Intravenous administration of AAV5 carrying a dystrophin GOI

B. An autologous CAR T cell therapy targeting B cells in a patient with B cell lymphoma

C. Autologous hematopoietic stem cells engineered to produce functional β-globin in a patient with β-thalassemia

3. Which of the following are components of an AAV vector?

A. Expression cassette, capsid, GOI

B. Promoter, cell wall, GOI

C. Expression cassette, liposome, GOI

4. Which product is a U.S.-approved AAV gene therapy with a Boxed Warning for serious liver injury and acute liver failure?

A. Zolgensma

B. Hemgenix

C. Adstiladrin

5. What toxicities are associated with administration of AAV gene therapy?

A. TMA, blindness, liver failure

B. Rash, myocarditis, loss of sense of smell

C. Liver failure, myocarditis, TMA

6. Which of the following statements is TRUE?

A. AAV confers a lower risk of inducing gene therapy-related cancers than lentiviral vectors.

B. AAV serotype does not influence what tissue will express the transgene product

C. Route of administration of a gene therapy is unlikely to contribute to its toxicity profile

7. Which situation would warrant administration of the complement inhibitor, eculizumab, in a patient that had received AAV gene therapy?

A. A patient complains of nausea the day after receiving gene therapy

B. A patient received gene therapy 5 days afo and has not urinated for 24 hours

C. A patient’s liver enzymes are elevated 6 months after receiving gene therapy

8. Which of the following statements is TRUE about viral vector production purification?

A. Proteins from the cell line used to propagate the vector may promote an inflammatory immune response

B. The main reason to remove empty capsids from the drug product is to reduce cost to the patient

C. Capsids containing partial or chimeric DNA sequences may provide a boost in efficacy of the therapy

9. A patient with sickle cell disease was hospitalized four times last year with severe pain due to vaso-occlusive crisis. The patient tells you that traditional symptom-managing medicines seem to be less effective than they used to be. Which FDA-approved gene therapies would be appropriate to discuss with this patient to educate them?

A. Hemgenix and Roctavian

B. Casgevy and Lyfgenia

C. Breyanzi

10. The FDA has approved several ex vivo gene therapies since 2017. A patient with -thalassemia learned from his doctor that he is a candidate for ex vivo gene therapy and asks you about the patient experience. Which of the following is the MOST appropriate education to provide?

A. He will be tested for antibodies to the gene therapy. If the test is negative, then he will be eligible for the therapy. He will receive an intravenous injection in the hospital or as an outpatient and will need to be monitored for several weeks or months for adverse effects and to determine if the therapy is working.

B. In an outpatient procedure, medical personnel will collect a large number of his white blood cells and modify them in a laboratory in a process that takes several weeks. When the cells are ready, he will go to a special treatment center and get chemotherapy to make room for the new cells. Once he receives the new cells, he will be closely monitored for several weeks, likely requiring an extended stay at the treatment center. He may experience severe, life-threatening adverse effects.

C. He will be given a drug so his body will produce more stem cells. Those cells will be collected and modified in a laboratory, in a process that may take 4-6 months. When the cells are ready, he will go to a special treatment center and get chemotherapy to make room for the new cells. For several months after receiving the new cells, he may need to stay at the treatment center for recovery and monitoring. At first, he likely will be prone to infections. He will have an increased risk for cancer, requiring monitoring for at least 15 years.

Pharmacy Technician Post Test (for viewing only)

GENES AS MEDICINES: GENE THERAPY

Pharmacy Technician Posttest

Learning Objectives

After completing this continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to

• Recognize patient populations that qualify for gene therapy

• Distinguish types of gene therapies

• Explain the patient experience for different types of gene therapies

• Describe the pros and cons of gene therapy.

1. Which of the following patients would qualify for an AAV9-based gene therapy?

A. A patient with a monogenic disease who has neutralizing antibodies to AAV9

B. A patient with a monogenic disease without neutralizing antibodies to AAV9

C. A patient with an undefined genetic disease without neutralizing antibodies to AAV9

2. Which of the following is an in vivo approach to gene therapy?

A. Intravenous administration of AAV5 carrying a dystrophin GOI

B. An autologous CAR T cell therapy targeting B cells in a patient with B cell lymphoma

C. Autologous hematopoietic stem cells engineered to produce functional β-globin in a patient with β-thalassemia

3. A single mom has been informed that her 6-year-old son with DMD is a good candidate for Elevidys gene therapy and asks you about the pros and cons of this treatment. Which of the following is the MOST appropriate education to provide?

A. The treatment may not completely cure her son’s disease; adverse effects are well understood; is very expensive

B. The treatment may completely cure her son’s disease; may have unknown adverse effects; is very expensive

C. The treatment may completely cure her son’s disease; may have unknown adverse effects; is not expensive

4. Which product is a U.S.-approved AAV gene therapy with a Boxed Warning for serious liver injury and acute liver failure?

A. Zolgensma

B. Hemgenix

C. Adstiladrin

5. What toxicities are associated with administration of AAV gene therapy?

A. TMA, blindness, liver failure

B. Rash, myocarditis, loss of sense of smell

C. Liver failure, myocarditis, TMA

6. Which of the following statements about patient challenges with different types of gene therapies is TRUE?

A. Patients receiving AAV gene therapy rarely have immune responses.

B. Patients receiving CAR T cell therapy for B cell lymphoma are less likely to experience Cytokine Release Syndrome than patients receiving an AAV gene therapy for a monogenic disease.

C. Patients receiving HSC therapy undergo long term safety monitoring due to increased risk of developing treatment-related cancers.

7. A patient with Hemophilia A is awaiting his AAV5 neutralizing antibody test results to determine whether he will be able to be treated with Roctavian. He asks you to explain about the potential outcomes and implications of the antibody test. Which of the following statements is TRUE?

A. If his test is negative (he does not have AAV5-specific antibodies), he will not be able to receive Roctavian.

B. If his test is negative (he does not have AAV5-specific antibodies), he will be able to receive Roctavian as many times as needed until he is cured.

C. If his test is positive (he does have the AAV5-specific antibodies), he will not be able to receive Roctavian.

8. A patient receives prophylactic oral corticosteroids starting 3 days before gene therapy begins. She then receives 2 sub-retinal injections of AAV vector 7 days apart and continues with tapering doses of the oral corticosteroids for 10 days. Which U.S.-approved AAV gene therapy product did she receive?

A. Luxturna

B. Zolgensma

C. Imlygic

9. A patient with sickle cell disease was hospitalized four times last year with severe pain due to vaso-occlusive crisis. The patient tells you that traditional symptom-managing medicines seem to be less effective than they used to be. Which FDA-approved gene therapies would be appropriate to discuss with this patient to educate them?

A. Hemgenix and Roctavian

B. Casgevy and Lyfgenia

C. Breyanzi

10. The FDA has approved several ex vivo gene therapies since 2017. A patient with -thalassemia learned from his doctor that he is a candidate for Zynteglo (ex vivo HSC gene therapy) and asks you about the patient experience. Which of the following is the MOST appropriate education to provide?

A. He will be tested for antibodies to the gene therapy. If the test is negative, then he will be eligible for the therapy. He will receive an intravenous injection in the hospital or as an outpatient and will need to be monitored for several weeks or months for adverse effects and to determine if the therapy is working.

B. In an outpatient procedure, medical personnel will collect a large number of his white blood cells and modify them in a laboratory in a process that takes several weeks. When the cells are ready, he will go to a special treatment center, and will receive his cells back. He will be closely monitored for several weeks, likely requiring an extended stay at the treatment center. He may experience severe, life-threatening adverse effects.

C. He will be given a drug so his body will produce more stem cells. His cells will be collected and modified in a laboratory, which may take 4-6 months. He will go to a special treatment center and get chemotherapy to make room for the new cells. He may need to stay at the treatment center for several months for recovery and monitoring. He will likely be prone to infections and be monitored for at least 15 years because of an increased risk for cancer.

References

Full List of References

References

- Issa SS, Shaimardanova AA, Solovyeva VV, Rizvanov AA. Various AAV serotypes and their applications in gene therapy: an overview. Cells. 2023;12(5):785. doi:10.3390/cells12050785

- Naso MF, Tomkowicz B, Perry WL, Strohl WR. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for gene therapy. BioDrugs. 2017;31(4):317-334. doi:10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5

- Shahryari A, Burtscher I, Nazari Z, Lickert H. Engineering gene therapy: advances and barriers. Adv Ther. 2021;4(9):2100040. doi:10.1002/adtp.202100040

- Dunbar CE, High KA, Joung JK, Kohn DB, Ozawa K, Sadelain M. Gene therapy comes of age. Science. 2018 Jan 12;359(6372). doi:10.1126/science.aan4672

- Chapa González C, Martínez Saráoz JV, Roacho Pérez JA, Olivas Armendáriz I. Lipid nanoparticles for gene therapy in ocular diseases. Daru. 2023;31(1):75-82. doi:10.1007/s40199-023-00455-1

- The free dictionary by Farlex. 2003-2023. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/

- 7. Bulcha JT, Wang Y, Ma H, Tai PWL, Gao G. Viral vector platforms within the gene therapy landscape. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):53. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00487-6

- GT Reference – Decoding the science of gene therapy glossary. 2022. Accessed February 16, 2024. https://www.gtreference.com/resources/glossary/

- American Medical Association. Gene therapy naming scheme. Accessed October 3, 2023. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/united-states-adopted-names/gene-therapy-naming-scheme

- Peters GL, Hennessey EK. Naming of biological products. US Pharm. 2020;45(6)33-36 June 18, 2020. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/naming-of-biological-products

- Wehrwein P. FDA approves Roctavian, the first gene therapy for hemophilia A. Managed Healthcare Executive. June 30, 2023. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.managedhealthcareexecutive.com/view/fda-approves-roctavian-the-first-gene-therapy-for-hemophilia-a

- Stein, R. Muscular dystrophy patients get first gene therapy. NPR. June 22, 2023. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2023/06/22/1183576268/muscular-dystrophy-patients-get-first-gene-therapy

- Pagliarulo N. FDA approves first gene therapy for hemophilia B. BioPharma Dive. Updated November 23, 2022. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/hemophilia-gene-therapy-fda-approval-hemgenix-csl-uniqure/636999/

- genehome bluebird bio. History and evolution of gene therapy. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.thegenehome.com/what-is-gene-therapy/history

- Blaese RM, Culver KW, Miller AD, et al. T lymphocyte-directed gene therapy for ADA- SCID: initial trial results after 4 years. Science. 1995;270(5235):475-480. doi:10.1126/science.270.5235.475

- Sibbald B. Death but one unintended consequence of gene-therapy trial. CMAJ. 2001;164(11):1612. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11402803/

- Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Garrigue A, Wang GP, et al. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(9):3132-3142. doi:10.1172/jci35700

- Cavazzana-Calvo M, Fischer A. Gene therapy for severe combined immunodeficiency: are we there yet? J Clin Invest. 2007;117(6):1456-1465. doi:10.1172/jci30953

- Pearson S, Jia H, Kandachi K. China approves first gene therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(1):3-4. doi:10.1038/nbt0104-3

- Daley J. Gene therapy arrives. Nature. 2019;576(7785):S12-S13. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03716-9

- Vaidya R. Realising the potential of AAV gene therapies. European Pharmaceutical Review. April 27, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.europeanpharmaceuticalreview.com/article/181742/realising-the-potential-of-aav-gene-therapies

- Aiuti A, Roncarolo MG, Naldini L. Gene therapy for ADA‐SCID, the first marketing approval of an ex vivo gene therapy in Europe: paving the road for the next generation of advanced therapy medicinal products. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9(6):737-740. doi:10.15252/emmm.201707573

- Luxturna. Package Insert. Spark Therapeutics, Inc.; 2022.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves CAR-T cell therapy to treat adults with certain types of large B-cell lymphoma. Updated March 21, 2018. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-car-t-cell-therapy-treat-adults-certain-types-large-b-cell-lymphoma

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves brexucabtagene autoleucel for relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. October 1, 2021. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-brexucabtagene-autoleucel-relapsed-or-refractory-b-cell-precursor-acute-lymphoblastic

- Cross R. CRISPR is coming to the clinic this year. Chemical & Engineering News. January 8, 2018. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://cen.acs.org/articles/96/i2/CRISPR-coming-clinic-year.html

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves innovative gene therapy to treat pediatric patients with spinal muscular atrophy, a rare disease and leading genetic cause of infant mortality. May 24, 2019. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-innovative-gene-therapy-treat-pediatric-patients-spinal-muscular-atrophy-rare-disease

- bluebird bio, Inc. bluebird bio announces EU Conditional Marketing Authorization for ZYNTEGLO Gene Therapy. June 3, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2024. https://investor.bluebirdbio.com/news-releases/news-release-details/bluebird-bio-announces-eu-conditional-marketing-authorization

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves new treatment for adults with relapsed or refractory large-B-cell lymphoma. February 5, 2021. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-treatment-adults-relapsed-or-refractory-large-b-cell-lymphoma

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves idecabtagene vicleucel for multiple myeloma. March 29, 2021. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-idecabtagene-vicleucel-multiple-myeloma

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves ciltacabtagene autoleucel for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. March 7, 2022. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-ciltacabtagene-autoleucel-relapsed-or-refractory-multiple-myeloma

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Roundup: September 20, 2022. September 20, 2022. Accessed February 16, 2024.

https://public4.pagefreezer.com/browse/FDA/01-10-2022T16:45/https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-roundup-september-20-2022

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first cell-based gene therapy to treat adult and pediatric patients with beta-thalassemia who require regular blood transfusions. August 17, 2022. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-cell-based-gene-therapy-treat-adult-and-pediatric-patients-beta-thalassemia-who

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first gene therapy for adults with severe hemophilia A. June 30, 2023. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapy-adults-severe-hemophilia

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First gene therapy to treat adults with hemophilia B. November 22, 2022. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapy-treat-adults-hemophilia-b

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first gene therapy for treatment of certain patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. June 23, 2023. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapy-treatment-certain-patients-duchenne-muscular-dystrophy

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first gene therapies to treat patients with sickle cell disease; December 8, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-gene-therapies-treat-patients-sickle-cell-disease

- Dunleavy K. Vertex, CRISPR's gene-editing therapy Casgevy wins early FDA nod to treat beta thalassemia. January 16, 2024. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/vertex-crispr-win-early-fda-nod-gene-therapy-casgevy-treat-beta-thalassemia

- Lundstrom K. Viral Vectors in gene therapy: where do we stand in 2023? Viruses. 2023;15(3):698. doi:10.3390/v15030698

- Wang K, Kievit FM, Zhang M. Nanoparticles for cancer gene therapy: Recent advances, challenges, and strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2016;114:56-66. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2016.10.016

- National Institutes of Health National Library of Medicine National Center for Biotechnology Information. ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed April 12, 2024. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/

- REQORSA Immunogene Therapy. Genprex. Accessed September 20, 2023. https://www.genprex.com/technology/reqorsa/

- Gillmore JD, Gane E, Taubel J, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo gene editing for transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6). doi:10.1056/nejmoa2107454

- Gaj T, Sirk SJ, Shui S, Liu J. Genome-editing technologies: principles and applications. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8(12):a023754. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a023754

- Godbout K, Tremblay JP. Prime editing for human gene therapy: where are we now? Cells. 2023;12(4):536. doi:10.3390/cells12040536

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approved cellular and gene therapy products. Updated: December 8, 2023. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/cellular-gene-therapy-products/approved-cellular-and-gene-therapy-products

47. Yescarta. Package Insert. Kite Pharma, Inc.; 2022.

- Kymriah. Package Insert. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2022.

- Tecartus. Package Insert. Kite Pharma, Inc.; 2023.

- Breyanzi. Package Insert. Juno Therapeutics Inc.; 2023.

- Abecma. Package Insert. Celgene Corporation; 2024.

- Carvykti. Package Insert. Janssen Biotech, Inc., 2023.

- Skysona. Package Insert. bluebird bio, Inc.; 2022.

- Zynteglo. Package Insert. bluebird bio, Inc.; 2022.

- Casgevy. Package Insert. Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2024.

- Lyfgenia. Package Insert. Bluebird bio, Inc.; 2023.

- Castaneda-Puglianini O, Chavez JC. Assessing and management of neurotoxicity after CAR-T therapy in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Blood Med. 2021;12:775-783. doi:10.2147/jbm.s281247

- Martins KM, Breton C, Zheng Q, Zhang Z, Latshaw C, Greig JA, Wilson JM. Prevalent and disseminated recombinant and wild-type adeno-associated virus integration in macaques and humans. Hum Gene Ther. 2023;34(21-22):1081-1094. doi:10.1089/hum.2023.134

- Wörner TP, Bennett A, Habka S, et al. Adeno-associated virus capsid assembly is divergent and stochastic. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1642. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21935-5

- Mietzsch M, Jose A, Chipman P, et al. Completion of the AAV structural atlas: serotype capsid structures reveals clade-specific features. Viruses. 2021;13(1):101. doi:10.3390/v13010101

- Daya S, Berns KI. Gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(4):583-593. doi:10.1128/cmr.00008-08

- Tseng YS, Agbandje-McKenna M. Mapping the AAV capsid host antibody response toward the development of second generation gene delivery vectors. Front Immunol. 2014;5. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00009

- Elmore ZC, Oh DK, Simon KE, Fanous MM, Asokan A. Rescuing AAV gene transfer from neutralizing antibodies with an IgG-degrading enzyme. JCI Insight. 2020;5(19). doi:10.1172/jci.insight.139881

- Schulz M, Levy D, Petropoulos CJ, et al. Binding and neutralizing anti-AAV antibodies: Detection and implications for rAAV-mediated gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2023;31(3):616-630. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.01.010

- Shirley JL, de Jong YP, Terhorst C, Herzog RW. Immune responses to viral gene therapy vectors. Mol Ther. 2020;28(3):709-722. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.01.001

- Li X, Wei X, Lin J, Ou L. A versatile toolkit for overcoming AAV immunity. FrontImmunol. 2022;13:991832. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.991832

- Gao G, Alvira MR, Somanathan S, et al. Adeno-associated viruses undergo substantial evolution in primates during natural infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(10):6081-6086. doi:10.1073/pnas.0937739100

- Samulski RJ, Muzyczka N. AAV-mediated gene therapy for research and therapeutic purposes. Annu Rev Virol. 2014;1(1):427-451. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085355

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. BRIEFING DOCUMENT Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Cellular, Tissue, and Gene Therapies Advisory Committee (CTGTAC) Meeting #70 Toxicity risks of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors for gene therapy. Sept 2-3, 2021. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/media/151599/download

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Chemistry, manufacturing, and control (CMC) information for human gene therapy investigational new drug applications (INDs). January 2020. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/chemistry-manufacturing-and-control-cmc-information-human-gene-therapy-investigational-new-drug

- Davidsson M, Negrini M, Hauser S, et al. A comparison of AAV-vector production methods for gene therapy and preclinical assessment. SciRep. 2020;10:21532. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-78521-w

- Clément N, Grieger JC. Manufacturing of recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors for clinical trials. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2016;3:16002. doi:10.1038/mtm.2016.2

- Srivastava A, Mallelab KMG, Deorkara N, Brophy G. Manufacturing challenges and rational formulation development for AAV viral vectors. JPharm Sci. Published online April 2, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.xphs.2021.03.024

- Penaud-Budloo M, François A, Clément N, Ayuso E. Pharmacology of recombinant adeno-associated virus production. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2018;8:166-180. doi:10.1016/j.omtm.2018.01.002

- Van der Loo JCM, Wright JF. Progress and challenges in viral vector manufacturing. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;25(R1):R42-R52. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddv451

- Kishimoto TK, Samulski RJ. Addressing high dose AAV toxicity – “one and done” or “slower and lower”?. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22(9):1067-1071. doi:10.1080/14712598.2022.2060737

- Chand D, Mohr F, McMillan H, et al. Hepatotoxicity following administration of onasemnogene abeparvovec (AVXS-101) for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. JHepatol. 2021;74(3):560-566. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.001

- Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy SA, Rodino-Klapac LR, et al. Current clinical applications of in vivo gene therapy with AAVs. Mol Ther. 2021;29(2):464-488. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.007

- Ertl HCJ. Immunogenicity and toxicity of AAV gene therapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:975803. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.975803

- Hordeaux J, Buza EL, Dyer C, et al. Adeno-associated virus-induced dorsal root ganglion pathology. Hum Gene Ther. 2020;31(15-16):808-818. doi:10.1089/hum.2020.167

- Sabatino DE, Bushman FD, Chandler RJ, et al. Evaluating the state of the science for adeno-associated virus integration: an integrated perspective. Mol Ther. 2022;30(8):2646-2663. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.06.004

- Ronzitti G, Gross DA, Mingozzi F. Human immune responses to adeno-associated Virus (AAV) vectors. Front Immunol. 2020;11. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00670

- Paulk N. Gene Therapy: It’s time to talk about high-dose AAV. Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. July 7, 2020. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://www.genengnews.com/insights/gene-therapy-its-time-to-talk-about-high-dose-aav/

- Vyjuvek. Package Insert. Krystal Biotech, Inc.; 2023.

- Adstiladrin. Package Insert. Ferring Pharmaceuticals; 2022.

- Imlygic. Package Insert. BioVex, Inc., a subsidiary of Amgen, Inc.; 2023.

- Zolgensma. Package Insert. Novartis Gene Therapies, Inc.; 2023.

- Hemgenix. Package Insert. UniQure, Inc.; 2022.

- Elevidys. Package Insert. Sarepta Therapeutics, Inc.; 2023.

- Roctavian. Package Insert. BioMarin Pharmaceutical Inc.; 2023.

- Prasad S, Dimmock DP, Greenberg B, et al. Immune responses and immunosuppressive strategies for adeno-associated virus-based gene therapy for treatment of central nervous system disorders: current knowledge and approaches. Hum Gene Ther. 2022;33(23-24):1228-1245. doi:10.1089/hum.2022.138

- Monahan PE, Négrier C, Tarantino M, Valentino LA, Mingozzi F. Emerging immunogenicity and genotoxicity considerations of adeno-associated virus vector gene therapy for hemophilia. J Clin Med. 2021;10(11):2471. doi:10.3390/jcm10112471

- Arruda VR, Favaro P, Finn JD. Strategies to modulate immune responses: a new frontier for gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2009;17(9):1492-1503. doi:10.1038/mt.2009.150

- Jordan SC, Lorant T, Choi J, et al. IgG endopeptidase in highly sensitized patients undergoing transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):442-453. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1612567