INTRODUCTION

Interprofessional collaboration crops up as a topic in many healthcare facility staff meetings. However, team members often don’t know how to collaborate effectively, so the conversation quickly trails off. Before you know it, everyone’s talking about the new espresso machine in the break room, and attendees are leaving the meeting without practicable advice.

Insufficient guidance on how to work together results in lost opportunities to improve patient outcomes. Consider the heart failure medication titration clinic that tested a pharmacist-driven titration protocol. Pharmacists collected data from vital signs and patient interviews to optimize drug dosages in heart failure, with statistically significant improvements in dosages.1 There was a key opportunity to collaborate here. The job description of someone on your team includes taking vitals and interviewing patients: the registered nurse (RN)!

Step one of effective teamwork is recognizing opportunities to put your heads together. Pain management took center stage when the multi-wave opioid overdose epidemic began in the 1990s.2 Plus, pain is an intrinsic characteristic of nearly all physical afflictions. What do you get when you combine these facts? An issue that’s causing significant problems and is ubiquitous— it’s ripe for collaboration.

What do RNs do? How can you partner with them? And what is this about pie?! This continuing education activity will guide you through those questions and provide an overview of trends in pharmacologic pain management. You’ll also learn several nonpharmacologic pain management strategies.

Note: “RN” and “nurse” are used interchangeably in this activity. Many of an RN’s responsibilities (comprehensive assessment and care plan creation in particular) are outside the scope of practice of, for example, a Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN).3,4,5

Furthermore, RNs are as ubiquitous as pharmacy professionals. Pieces of this activity apply mostly to RNs in specific settings such as hospitals. However, it’s helpful to keep in mind that RNs work in skilled nursing facilities, telehealth, schools, home healthcare, correctional facilities, and more. Considering these different areas can keep your gears turning when deducing how to crack the nut of collaboration.

THE NURSE’S ROLE

Working with every member of the healthcare team necessitates understanding everyone’s role. Ask five people what an RN does, and you’ll probably hear five different answers. One misconception is that the nurse is an extension of the doctor. On the contrary, nurses have their own chain of command and overarching objectives in patient care. The doctor’s focus centers around an injury's or illness’ physiological implications, whereas the nurse manages how the condition affects the patient.6,7,8 The SIDEBAR about nursing diagnoses later in the activity differentiates these concepts.

What nurses do is part of the picture—the other part is how they do it. RNs use communication and four of their five senses (hopefully they’re not tasting anything, anyway…) to establish and continually revise a care plan. The framework for a care plan is known as ADPIE.4,8

We’ll circle back to RNs, care plans, and that pie you were promised. Let’s look at pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain management methods first, and we’ll connect the dots later.

PAIN MANAGEMENT

At its most fundamental level, every pain treatment is pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic. Both have the power to help the patient, but any number of minutiae about the patient and condition dictates which therapy or combination of therapies is best.

Pharmacologic Pain Management

Numerous factors including etiology, coexisting conditions (e.g., pregnancy, disease), and pain type (e.g., neuropathic, pleuritic, visceral) steer analgesic selection. This activity primarily categorizes pharmacologic therapies by classifying pain as acute or chronic. You will understand the reason for this delineation when you read about nursing diagnoses.

Considerations for cancer pain and the geriatric and pediatric populations close the section.

Acute Pain

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies pain lasting three months or less as acute.9 Today’s analgesic guidance for acute pain centers around multimodal strategies, due in part to the opioid crisis. These strategies’ end goal is effective pain relief with minimal adverse effects.9,10 “Balanced analgesia” is the term for this concept. Its underlying principle is to reduce opioid and non-opioid dosages by attacking pain from multiple angles.10

One such approach is channels-enzymes-receptors targeted analgesia, or CERTA. This approach boils down to pathways and progression. Namely, practitioners can achieve balanced regimens by deploying interventions that act on different pathways and progressing to more potent therapies as needed.10

A balanced and stepwise approach to acute pain therapies comes to life in Table 1. As with all matters in healthcare, patient-specific care is paramount. For instance, although opioids are not necessarily first-line therapies, a non-opioid trial is not required before initiating opioid therapy.9

Table 1. Pharmacologic Medications for Acute Pain10,11

| Topical |

| · Diclofenac or ibuprofen for musculoskeletal injuries

· Camphor, menthol, and clove oil for headache or muscle pain |

| |

| Mild to moderate acute pain |

| Medication |

Example indications |

What to know |

| Acetaminophen |

Headache, sprain |

· Combine with NSAIDs for postoperative pain

· Limit 75 mg/kg/day or 4,000 mg/day (2,000 mg/day in hepatic disease and alcohol use disorder) |

| NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, ketorolac, meloxicam, celecoxib) |

Migraine, postoperative pain, low back pain |

· Patient might need a PPI

· Combinations with acetaminophen improve analgesia |

|

| Moderate to severe acute pain |

| Medication |

Example indications |

What to know |

| [Opioid] + [acetaminophen or NSAID]

(HYDROcodone/acetaminophen, HYDROcodone/ibuprofen, oxyCODONE/acetaminophen) |

Fracture, postoperative pain |

Combinations reduce the opioid dosage needed |

| Dual-action opioids (traMADol, tapentadol) |

Therapeutic failure of other agents |

· Risk for opioid use disorder and serotonin syndrome

· TraMADol reduces seizure threshold |

| Full-agonist opioids (oxyCODONE, morphine, HYDROmorphone, fentanyl) |

· Risk for sedation, respiratory depression, and opioid use disorder

· 3-day limit |

NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

PPI = proton pump inhibitor

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) enter virtually every discussion about acute pain. Note that this drug class may cause complications in patients with cardiovascular or renal impairment or a history of gastrointestinal (GI) bleed.9,12

Adverse GI effects of NSAIDs are less likely to occur with a selective COX-2 inhibitor such as celecoxib. In turn, the patient is less likely to need a PPI (proton pump inhibitor) than with other NSAIDs. Eliminating a PPI lowers costs and helps inhibit polypharmacy’s adverse effects.11

Is the first column of Table 1 reminiscent of alphabet soup? Drug names that resemble one another—aptly named “look-alike and sound-alike” (LASA) drugs—present an opportunity for unfortunate drug mix-ups. The LASA Drugs SIDEBAR has more information about these drug name pairings.

SIDEBAR

LASA Drugs13,14

Nurses learn about and watch out for look-alike and sound-alike (LASA) drugs. However, the pharmacy team—the pharmacy technician, in particular—is the first line of defense in preventing related errors.

Mix-ups between HYDROmorphone and morphine constitute an example of a common and serious LASA-related problem. Some ways to help prevent med errors involving these two drugs include

- Placing each agent and strength in its own bin or drawer.

- Looking for tall man lettering: HYDROmorphone.

- Stating the name of the drug before providing it to a patient for confirmation.

- Using brand names for additional confirmation.

The LASA list is a living document. How can you keep up to date on changes and additions? The ISMP (Institute for Safe Medication Practices) maintains this table—find it here.

| Drug name |

Confused drug name |

| acetaminophen |

acetaZOLAMIDE |

| buprenorphine |

HYDROmorphone |

| carBAMazepine |

OXcarbazepine |

| codeine |

Lodine |

| DULoxetine |

Dexilant, FLUoxetine, PARoxetine |

| EPINEPHrine |

ePHEDrine |

| fentaNYL |

ALfentanil, SUFentanil |

| gabapentin |

gemfibrozil |

| HYDROcodone |

oxyCODONE |

| HYDROmorphone |

buprenorphine, hydrALAZINE, hydrOXYzine, morphine, oxyMORphone |

| ketamine |

ketorolac |

| ketorolac |

Ketalar, ketamine, methadone |

| methadone |

dexmethylphenidate, ketorolac, memantine, Mephyton, Metadate, Metadate ER, methylphenidate, metOLazone |

| morphine* |

HYDROmorphone |

| oxyCODONE |

HYDROcodone, oxybutynin, OxyCONTIN, oxyMORphone |

| traMADol |

traZODone |

*Morphine has a non-concentrated oral liquid form and a concentrated oral liquid form.

Note: Names with first letter capital letters indicate trade names.

PAUSE AND PONDER: Where can you refer patients if you suspect drug abuse, or if a patient requests such a resource for himself or a loved one?

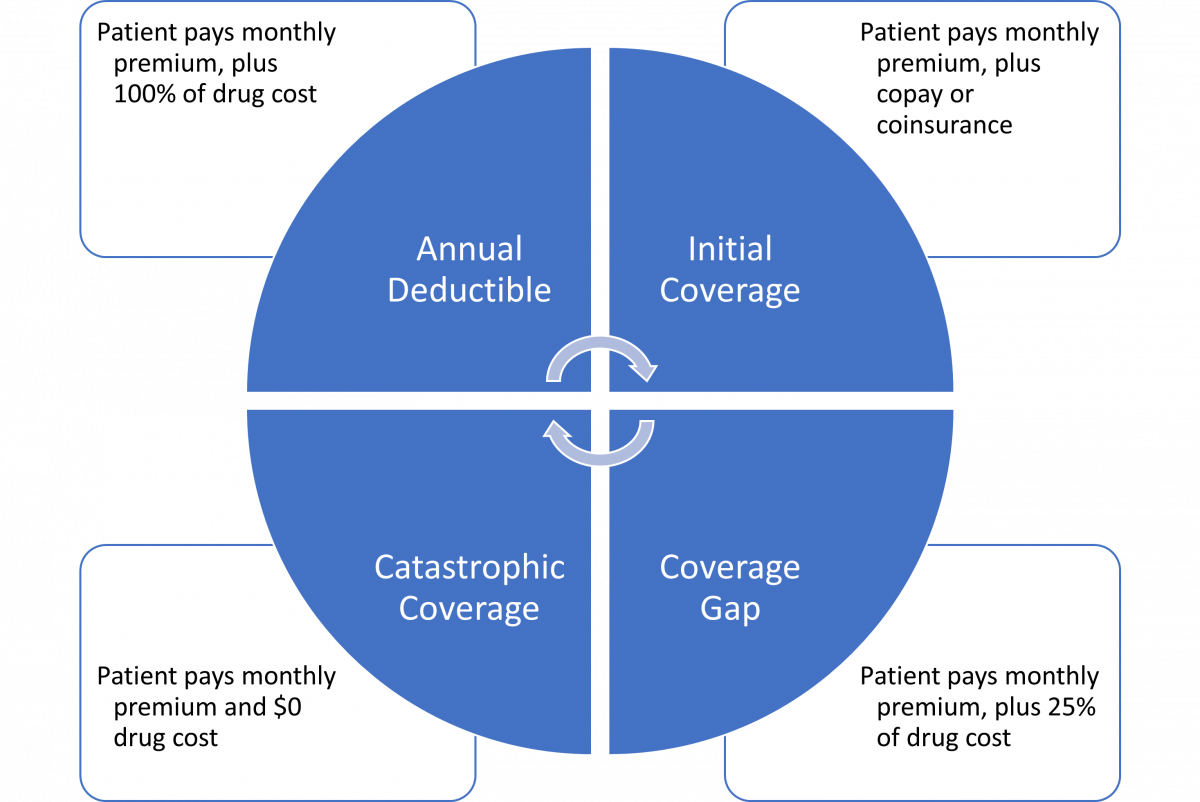

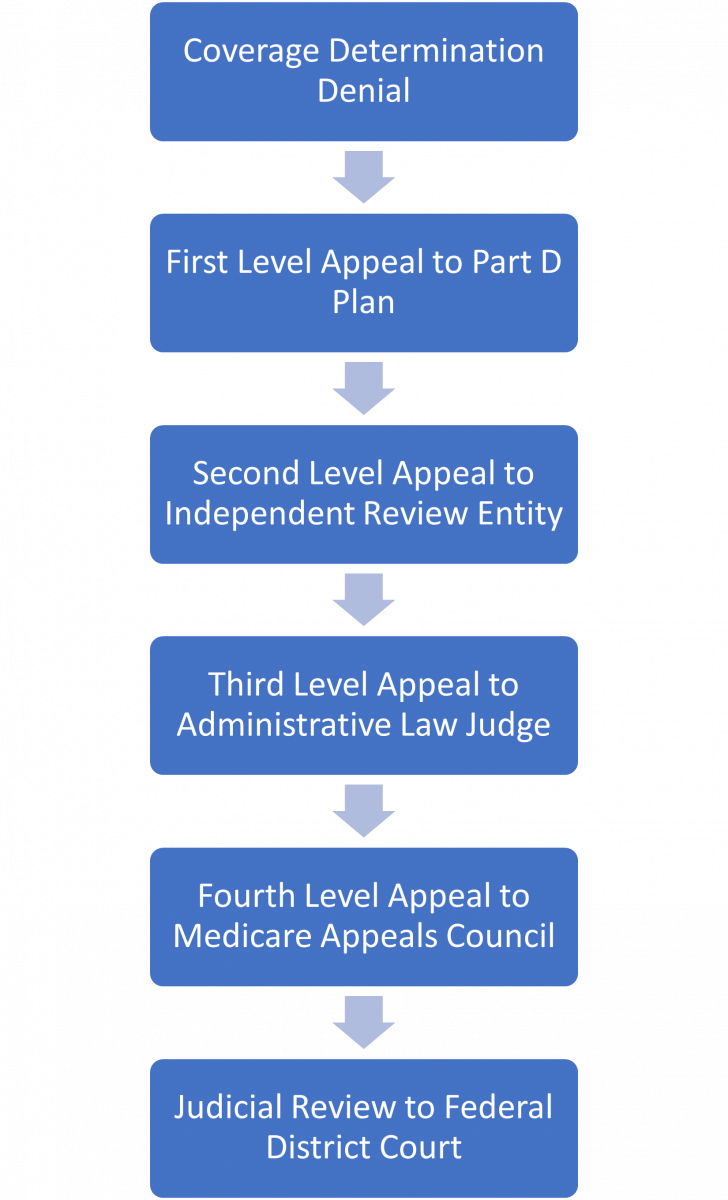

Chronic Pain

Per the CDC, pain lasting longer than three months is chronic. Following are select chronic pain management recommendations from the CDC Clinical Practice Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Pain.9 Practitioners who prescribe opioids should read this comprehensive guideline in full—click here to access this free document.

- Use nonopioid therapies to the greatest extent possible.

- Discuss the risks and benefits of opioids with the patient.

- Prescribe immediate-release formulations at the start of opioid therapy.

- Start with the lowest dosage possible for opioid-naïve patients.

- Evaluate the risk/benefit balance before increasing dosages.

- Do not discontinue or rapidly decrease dosages in the absence of a life-threatening condition.

- Evaluate risks and benefits 1-4 weeks after starting therapy and periodically thereafter.

- Use a prescription drug monitoring program to help evaluate the risk of overdose.

- Evaluate the risk/benefit balance of concurrent benzodiazepines.

Extensive news coverage of the opioid crisis means that even individuals far removed from healthcare are wary of opioids. Serious adverse effects and associations include respiratory depression, overdose, opioid use disorder, falls, and death from all causes. All healthcare providers must inform patients that benzodiazepines, alcohol, and some illicit drugs increase the risk for respiratory depression.9,15

Common adverse effects of opioids include constipation, nausea/vomiting, and drowsiness. These effects might cause patients to discontinue therapy. Practitioners should warn against abrupt opioid discontinuation, explaining that withdrawal syndrome could result. They should inform patients that certain behaviors can mitigate adverse effects, such as hydration, fiber intake, and exercise for constipation.9,15

What alternatives to opioids exist? Other drug classes for chronic pain include NSAIDs, anticonvulsants (pregabalin, gabapentin), and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; DULoxetine, milnacipran).9 These are associated with their own risks to consider when planning a patient’s drug regimen.

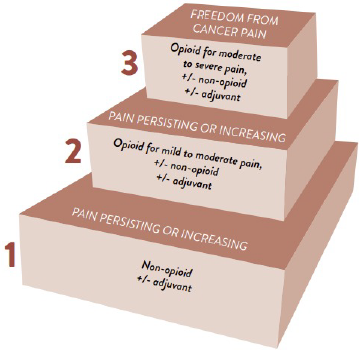

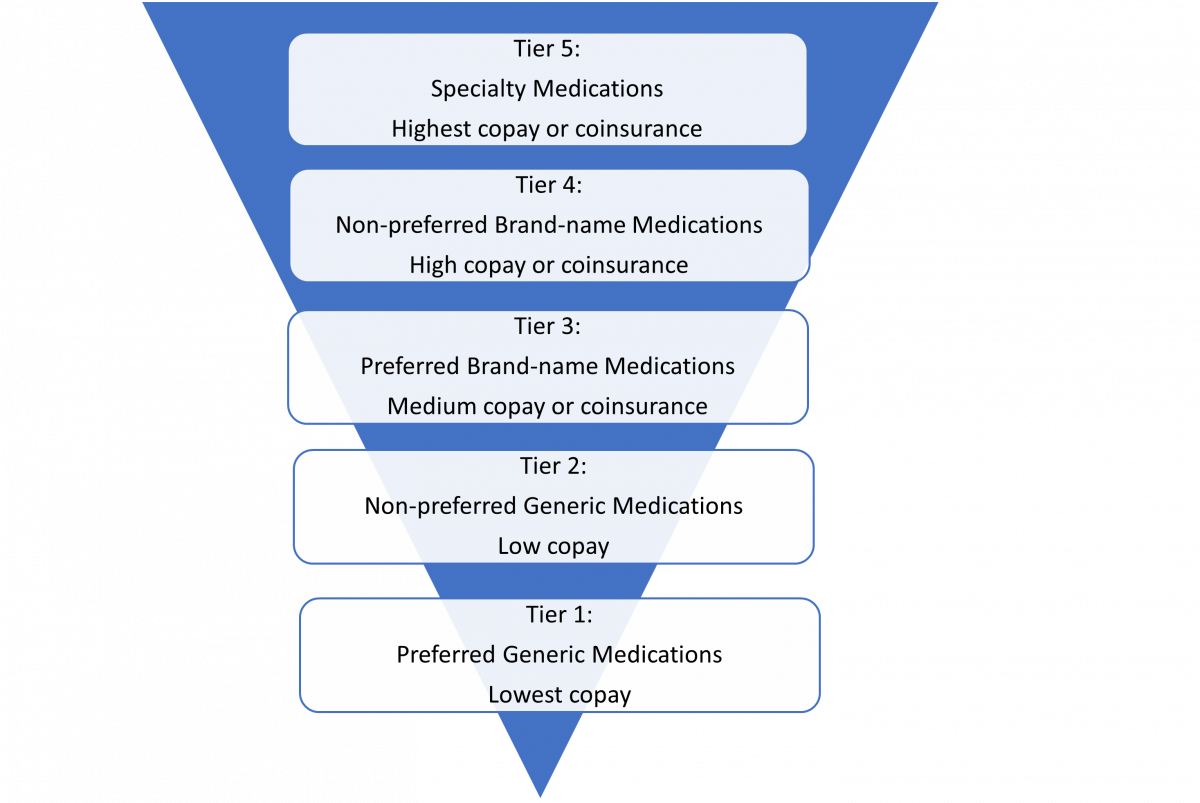

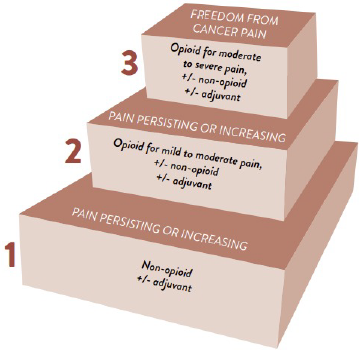

Cancer Pain: The WHO Analgesic Ladder

The World Health Organization (WHO) released an algorithm in the mid-1980s to steer pain management planning in cancer, as this condition warrants unique considerations.16

The WHO analgesic ladder, replicated in Figure 1, is a major element of the algorithm. It provides visual guidance for prescribing and deprescribing adjuvant, non-opioid, and opioid analgesics for varying pain severities. Following are select examples16,17:

- Adjuvants: antidepressants (amitriptyline, DULoxetine), anticonvulsants (gabapentin, carBAMazepine), corticosteroids, cannabinoids

- Non-opioid analgesics: NSAIDs (ibuprofen, ketorolac), acetaminophen

- Weak opioids: HYDROcodone, codeine, traMADol

- Potent opioids: morphine, HYDROmorphone, methadone, fentaNYL, oxyCODONE, buprenorphine

Figure 1. WHO Analgesic Ladder17

Reproduced from WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents, World Health Organization, Annex 1: Evaluation of Pain, P. 70, 2018.

Note that the model has criticisms. For instance, it can lead to the erroneous inference that NSAIDs are safe since they are the ladder’s entry point. Furthermore, the WHO designed the ladder for simplicity, causing clinicians to reference it outside the bounds of cancer pain. However, research findings point to abandoning the algorithm in chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies that better control CNCP while limiting opioid usage exist.16,18,19

The WHO analgesic ladder is just one constituent of the extensive WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents (click here to access). Reference this manual for further guidance in cancer pain management, such as the following principles that should accompany the ladder17:

- By mouth: Use the oral route of administration when possible.

- By the clock: Administer pain medication at set intervals rather than pro re nata (PRN).

- For the individual: Tailor pain management to the individual; the ladder is only a guideline.

- With attention to detail: Base first and last doses on sleep/wake times. Write down drug and administration regimen information for caretakers. Inform patients of potential side and adverse effects.

Geriatric Considerations

Common origins of pain in the geriatric population are arthritis, postherpetic neuralgia, and cancer. And although more common as we age, pain is not a normal element of the aging process.20 However, practitioners must consider certain essential physiological changes when prescribing for older patients. These include increased body fat and decreased rates of GI absorption and renal and hepatic clearance.21

Also notable is that older adults often experience insufficient pain relief, such as when they cannot communicate the presence or degree of pain.21

Drugs from several classes indicated for pain appear in the AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults (AGS: American Geriatric Society). These classes include benzodiazepines, certain antidepressants, skeletal muscle relaxants, and NSAIDs.22 Healthcare providers should check this publicly accessible document (click here to access) when prescribing or reviewing an older adult’s medications.

Consider acetaminophen to be the first-line analgesic for pain in the older adult. Hospitalized older patients with oral intake restrictions might require intravenous (IV) acetaminophen. If acetaminophen is insufficient, NSAIDs follow. They are relatively safe for short-term use such as during an emergency room visit, although the provider should consider including a PPI. In terms of safety and timelines, NSAID use increases the risk for cardiac events after just one week of regular use. Topical formulations can be an effective alternative in the face of GI or cardiovascular contraindications to NSAIDs.21,23

Prescribers should also start opioids at a lower dosage in geriatric patients. Morphine and HYDROmorphone can be initial analgesics, but note that their metabolites are excreted by the kidneys. Therefore, fentaNYL might be a better option for the older patient with renal impairment.21,24

Pediatric Considerations

Pain control is especially important for pediatric patients since unmanaged pain can develop into hyperalgesia (excessive response to pain).25,26

Unlike with other populations, the first-line pain therapy for pediatric patients isn’t part of the formulary—it’s nonpharmacologic intervention. Methods range from breastfeeding for the youngest to distraction with video games for the teens.27

If nonpharmacologic techniques are insufficient, the clinical team needs to make route of administration a top consideration in drug therapy. They should start with the least invasive route, considering non-parenteral routes first (inhaled, intranasal, oral, rectal, topical).27 Table 2 lists common medications by route.

Table 2. Pharmacologic Medications for Pediatric Patients27

| Route of administration |

Common medications |

| Topical |

· Lidocaine

· Lidocaine and prilocaine

· Lidocaine, EPINEPHrine, and tetracaine

· Ethyl chloride

· Pentafluoropropane and tetrafluoroethane |

| Oral |

Acetaminophen, ibuprofen, naproxen, sucrose (infants) |

| Intranasal |

Ketamine, fentaNYL, HYDROmorphone |

| Inhaled |

Ketamine, nitrous oxide |

| Intravenous |

Ketorolac, acetaminophen, ketamine, morphine, HYDROmorphone, fentaNYL |

Here’s a PRO TIP: Children are not simply “small humans.” They are physiologically different from adults, necessitating special considerations in pharmacology even within sub-stages of the broad category of pediatrics. In other words, treatment for a 4-year-old cannot be the same as for her 15-year-old sister.27,28

Moreover, when prescribing for the pediatric population—which often involves weight-based dosing—clinicians must consult prescribing guidelines specific to the pediatric population. Calculating the pediatric dosage by extrapolating the adult dosage-to-weight ratio could yield a subtherapeutic or supratherapeutic dosage.27,28

PAUSE AND PONDER: Patients with painful conditions generally fear or dread this aspect of their affliction. What are some ways you can respond when patients communicate these feelings, such as when expressing worry that their analgesic prescriptions will be insufficient?

Nonpharmacologic Pain Management

Nonpharmacologic pain control is so important that the Joint Commission stipulates its availability in hospitals.29 Supplementing drug therapy with nonpharmacologic interventions further reduces pain and does not present significant risk.9

Inpatient nurses are generally with patients for a short period (average length of acute care stay is approximately 6.5 days), so they might use the same techniques for acute and chronic pain.30 Hence, this section doesn’t focus on such a distinction, but Table 3 lists statistics-based guidance regarding nonpharmacologic therapy specifically for chronic pain.

Table 3. Nonpharmacologic Strategies for Chronic Pain31

| Pain type |

Term |

Successful modality(ies) |

| Chronic low back pain |

Short |

Psychological therapy, massage, stress reduction, acupuncture |

| Intermediate |

Psychological therapy, spinal manipulation, yoga |

| Long |

Psychological therapy |

| Chronic neck pain |

Short |

Low-level laser therapy |

| Osteoarthritis pain |

Short |

Exercise |

| Fibromyalgia |

Short |

Exercise |

| Intermediate |

Exercise |

Short term: 1 to < 6 months

Intermediate term: ≥ 6 to < 12 months

Long term: ≥ 12 months

Note 1: “Term” is the length of time between intervention and assessment.

Note 2: This table only includes data with moderate strength of evidence.

Note 3: The research did not find high-quality evidence for nonpharmacologic pain relief for chronic tension headaches.

Because this continuing education activity centers around collaborating with the RN, the nonpharmacologic techniques detailed omit those outside the RN’s scope of practice. Interested learners can seek other literature for information about the following examples of such modalities32,33:

- Ablation

- Acupuncture

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Counseling

- Electrical nerve stimulation

- Physical and occupational therapy

The coming subsections cover some techniques the RN can apply. But any healthcare provider can employ these strategies, wherever the patient is, and without preparation. Plus, you can suggest these ideas to the RN during rounds or team meetings.

Journaling

Patients can journal about their pain to reduce its intensity and its interference in their daily life. Researchers who conducted a study in CNCP had 72 patients journal quantitative information each day. Included were a body pain map, pain intensity, and ratings for disturbance to activities and quality of life. Patients recorded qualitative data at the end of each week, including pain management methods and communication with others about pain.34

How did journaling help?

- Patients understood their pain better.

- Providers supported and communicated with patients more effectively.

- Journals served as an outlet for negative emotions.

Here’s another PRO TIP: The study found that journaling was effective only in patients with adaptive coping mechanisms—healthy stress management techniques, such as exercise or religious practices. Consider other nonpharmacologic modalities for patients who use avoidance or other maladaptive strategies.34

Mind-Body Interventions

When advising patients, it is as important to know what works as it is to know what doesn’t work. Claims regarding mind-body techniques for pain relief abound, but are any effective?

A study on mind-body interventions divided 244 participants into three parallel arms. Of 159 participants undergoing a mind-body intervention, researchers led 86 in mindfulness training and 73 in hypnotic suggestion. The control group of 85 received training regarding pain management strategies.

The mind-body interventions provided significantly more pain relief than the education session. Specifically, 15-minute sessions of the following techniques reduced pain immediately35:

- Mindfulness training (23% pain reduction): patients listened to a script guiding them to focus on sensations and breathing and to accept pain and negative thoughts

- Hypnotic suggestion (29% pain reduction): patients listened to a script guiding them to visualize floating in a peaceful location and to manifest temperature or tingling in place of pain

The control group experienced a pain reduction of just 9%.

These methods do not require specially credentialed personnel—study interventionists received training from a professional certified in clinical hypnosis. Hence, the healthcare team does not need to consult a hypnotherapist to apply the hypnotic suggestion technique with each patient.35

Mind-body exercise is on the table, too. Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines (OARSI) now name tai chi and yoga as Core Treatments for knee osteoarthritis.12

Distraction

Ever plop down in front of the TV to take your mind off a troubling issue? There’s science behind that! Multiple hypotheses attempt to pin down the psychology and physiology behind distraction and pain relief. Many postulate that the mind has the capacity to focus on or process only so much at a time. When people make their brains focus on something else, suddenly the pain can’t demand so much attention.36,37,38

Unfortunately, many studies evaluating these hypotheses and methodologies are inconclusive or poorly designed. Nevertheless, one can accept several useful findings relatively confidently, summarized next.36

Pain perception occurs differently in chronic pain than in acute pain. Research findings do not support distraction as an effective pain management strategy in chronic pain.36

Conversely, distraction can mitigate acute pain. For instance, visual distraction—particularly if the medium is interactive—is effective in children and adults. Participants in various studies reported improved pain characteristics during activities such as playing simplistic computer games or using a virtual reality (VR) headset.36,39,40

One study measured how long 79 children could keep a hand submerged in cold water (painful stimulus) while playing a VR video game. Each child underwent the test while watching a recording of that same game and, as a control, while simply wearing the headset. Urn randomization counterbalanced the order of the two distraction conditions. Passive visual distraction (watching the game) increased pain tolerance significantly, and active distraction (playing the game) increased it further.39

In a similar study (N = 107), adults played a simple, slow computer game while a heating pad provided a painful stimulus. Participants’ pain perception variables improved during gameplay (higher pain threshold and tolerance, lower intensity).40

Some research reveals no correlation between pain and auditory stimuli such as a recorded description of a scene or audible tones study participants were to react to.36 But what happens with auditory input the listener actually enjoys? Investigating the relationship between music and pain in adults corroborates its analgesic effect, particularly when the patient chooses or approves the genre.41,42 In fact, some investigations found pain relief to be so significant that patients required less opioids and other analgesics.42,43,44

One such study evaluated the pain levels and morphine requirements of patients undergoing the same procedure by the same surgeon and analgesic protocol. The researchers randomized 75 patients into blocks of 25. All patients wore headphones connected to a CD player intraoperatively and postoperatively. One block’s headphones were connected to CD players playing soft music intraoperatively and sham CD players postoperatively. Sham CD players displayed track numbers on their indicators but played no audio. The second block received sham CD players intraoperatively and heard music postoperatively. The control group had sham CD players during both phases.44

Both blocks receiving the intervention reported lower pain ratings in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) compared with the control group. Furthermore, total morphine required in the PACU was lower for the intervention blocks—1.2 mg for postoperative listeners, 2.3 mg for intraoperative listeners, 3.6 mg for the control group.44

Research does not support sweeping generalizations regarding music for pain management in pediatrics. A substantial proportion of pertinent studies report inconclusive results or have insufficient sample sizes. However, two meta-analyses (429 and 5601 participants) found music therapy to reduce pain in pediatric cancer and in needlestick, procedural, and postoperative pain.45,46

Additional methods

The nurse’s toolbelt contains an array of nonpharmacologic pain control tools, all appropriate in different contexts. A 9-year-old might enjoy a large-piece puzzle, which is unlikely to satisfy a teen. A patient with mild to moderate pain who has been resting in bed for several days might like to attempt guided imagery or meditation. That’s probably not the case for a patient wheeled into the ER following traumatic amputation of a limb.

Hot and cold therapy are yet another option, but they require training. Practitioners must know when heat versus ice is appropriate, how to apply different equipment and media, and how to assess for effectiveness and warning signs. As such, facility policy may stipulate provider prescription before applying heating pads, ice packs, and other such therapies.

THE ADPIE FRAMEWORK

Take a slow, deep breath. Smell that blueberry filling inside its flaky, buttery home? Or that warm layer of pecans awaiting a cool scoop of vanilla? It’s time for pie…

Overarching Concept

ADPIE is an acronym describing the five elements of the nursing process: assess, diagnose, plan, implement, evaluate. It’s the framework that shapes everything the RN does.4,8

PAUSE AND PONDER: The Joint Commission once endorsed pain as the fifth vital sign. The organization rescinded the statement following substantial backlash.47 Does pain’s inclusion as a fundamental component of assessment increase the likelihood of treatment or result in overzealous prescribing of analgesics?

ADPIE Letter by Letter

A: Assess

Assessment is the core of nursing and the foundation of the nursing process. It involves collecting objective and subjective data about a patient’s physical and non-physical status (emotional, spiritual, economic, etc.).8,48,49 Lab values, comorbidities, the patient’s and family’s statements, diagnostic imaging results, past medical history, physical assessment findings, and much more all coalesce into a comprehensive assessment.

Assessment sometimes lacks sharp boundaries. Take this example: A nurse passes an LPN pushing a newly admitted patient onto the unit in a wheelchair. The patient has a furrowed brow and is clutching her hip. The patient is not yet under the nurse’s care, nor did the nurse step in front of the wheelchair and proclaim, “I am now assessing you.” Yet the nurse has already assessed through passing observation that this patient might have pain in her hip, which requires further investigation.

Put simply, the adept nurse is constantly observing for key insights into the patient’s overall condition!

D: Diagnose

Recall that the nurse’s role is not to resolve an affliction, but rather to manage how it affects the patient. Just like the pharmacy team, nurses cannot diagnose medical conditions. ADPIE diagnoses are nursing diagnoses, not medical diagnoses. Entire books are dedicated to nursing diagnoses, and while in-depth coverage is outside the scope of this continuing education activity, the Nursing Diagnoses SIDEBAR contains more information.

NANDA International, Inc. is an industry-standard organization that defines nursing diagnoses.* Their taxonomy is called “NANDA-I”; however, this is not the only taxonomy, and many healthcare facilities develop their own. When it comes to pain as a nursing diagnosis, these taxonomies often list acute pain and chronic pain as the primary pain-related categories.8,50,51

*Before 2002, “NANDA” stood for “North American Nursing Diagnosis Association.” It is no longer an acronym.52

SIDEBAR

Nursing Diagnoses4,8,48,53

Nursing diagnoses have multiple components, starting with the diagnosis itself. This can come from taxonomies such as NANDA International, Inc., the ICNP (International Classification for Nursing Practice), or the facility where the RN practices.

Take pneumonia as an example to illustrate nursing diagnoses and how they differ from medical diagnoses. The medical diagnosis is simply “pneumonia,” potentially with a qualifier such as “bacterial.” This is what the provider treats.

When selecting diagnoses, the RN considers how the illness affects the specific patient. Virtually all patients with pneumonia will have a nursing diagnosis of ineffective airway clearance.

This is a valid nursing diagnosis because the nurse can “do something for it” (and it’s in the NANDA-I taxonomy). The nurse can teach the patient turn, cough, and deep breath (TCDB) exercises to alleviate this. If the patient has impaired mobility (another nursing diagnosis), the RN can also turn the patient in bed periodically to help different areas of the lung inflate.

Say the patient is a star athlete and single father of three. The RN has additional diagnoses to consider now: anxiety, caregiver role strain, and insomnia. These issues reflect how pneumonia affects this patient, and the RN can take several steps to alleviate the problems. Potential steps include teaching anxiety management techniques, helping source childcare resources, and collaborating with the provider and pharmacist for pharmacologic sleep aids.

The other parts of a nursing diagnosis’ anatomy vary based on complex considerations, but they generally include

- Related factors, or etiology—in the case of pneumonia, the offending species

- Defining characteristics—objective and subjective data collected upon assessment that supports the nursing diagnosis

Having a strong handle on nursing diagnoses is a fundamental skill for an RN, as these short statements guide the outcomes and interventions.

Back to our new arrival on the unit, who the RN has learned is an 85-year-old woman named Sheila. Upon further assessment, Sheila shows signs of infection at the incision of her recent total hip replacement (THR). Sheila reports a pain level of 5 on a scale of 1 to 10 as part of the admission assessment. Multiple nursing diagnoses apply (to these and any number of other assessment findings), but the nurse notes acute pain in particular.

P: Plan

Now that the nurse has assessed the patient and made the relevant diagnoses, planning begins. Nurses plan outcomes, or goals, that are SMART: specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and timed. They also plan interventions—ways to accomplish each outcome—that are evidence based wherever possible.4,8,48

A simple way to look at these two components of the Plan stage is that the outcomes are what the patient will do, and the interventions are what the nurse will do.

Let’s zoom in on outcomes first. Every nursing diagnosis needs one outcome statement. Relevant data from the entire picture—Sheila’s comprehensive assessment findings—feeds into each goal.48 We’ll define Sheila’s outcome statement for the diagnosis of acute pain as follows: Report pain of 0 to 3 on a 10-point scale by discharge. Where does the “realistic” criterion fit? Sheila’s condition is acute, and her reported pain level was 5. A rating of 0 to 3 is probably realistic for her, although it likely wouldn’t be for a patient with stage IV bone cancer.

Now for those interventions. What can or should the nurse do? Well, she must perform at least one action that supports meeting the outcome. And she’ll need to assess metrics relevant to the outcome (in this case, pain level).

All other interventions come from a complex web influenced by the nurse’s training and clinical experience. Patient teaching, collaborating, recommending and evaluating labs, and supporting nutrition and hydration are other facets of virtually all care plans. In any case, every intervention should support achievement of the respective outcome statement.

Here’s a small sample of what the RN might plan as the actions she will take (i.e., interventions) for Sheila:

- Administer pain medication as prescribed; collaborate with provider and pharmacist to determine appropriate therapy.

- Encourage distraction as nonpharmacologic pain management.

- Perform wound care.

- Teach hand and wound hygiene techniques.

- Assess pain every four hours.

Science drives the nursing process. Each intervention supports achievement of the outcome. The outcome represents a resolution to the nursing diagnosis. The diagnosis comes from assessment data. Here’s how it all comes together: Every step of the nursing process flows into the next.8 The nurse’s actions are not haphazard.

I: Implement

The implementation stage involves conducting the plan: doing, delegating, and documenting.8 The RN acts independently for certain actions, such as performing wound care and administering medications.48

However, no one in healthcare acts alone. The implementation stage is where collaboration happens!4 That’s right, this is when the RN is thinking about you, the pharmacy team. Does the RN need the pharmacist’s help teaching a patient about self-administration of a new prescription? Maybe she needs some help from the pharmacy technician for a patient who needs a special drawer in the drug dispensing cabinet. In Sheila’s case, the RN collaborates with the provider and pharmacist to discuss pharmacologic analgesia.

E: Evaluate

How do we know we’ve made a positive difference for the patient? We go back and evaluate. The RN reassesses Sheila to determine whether her situation improved. If Sheila rates her pain as 3 or lower, the goal was met, and the RN can focus on other diagnoses. If Sheila says her pain is 4 or higher, the goal is unmet, and the RN must modify the care plan.8 Maybe she could try another nonpharmacologic strategy. Perhaps the pharmacist and provider need to increase dosages, consider a drug with a different method of action, or change the route of administration.

NOTES ABOUT ADPIE

Like the Song that Doesn’t End

The nursing process is an endless loop. After classifying each goal as met or unmet, the RN may continue, modify, or discontinue that part of the care plan.4,8

If a goal is unmet, the RN must revise something. Often, he must add or modify an intervention. Perhaps, though, the goal was unrealistic. Or could the assessment have been incorrect? If a patient was admitted while comatose, certain assessment data could be erroneous if his next of kin provided an inaccurate past medical history.

IE-PIE-PIE

You were promised PIE, yet collaboration with the pharmacy team wasn’t mentioned until implementation (I). What gives?

The RN is headed your way during the first round of implementation, but once you’re roped in, you can be involved in each iterative loop, particularly in the P-I-E.

Remember that assessment (A) is a key function of the nurse. Pharmacists should certainly feel free to assess patients, but for the purpose of effective collaboration, they need to recognize that a team member is performing continuous assessment. Diagnosis (D) is solely the responsibility of the nurse. Therefore, each round of PIE is when other members of the healthcare team should proactively check in. The nurse has to deal with the ads, and you just get the pie!

Too Cool for Nursing School

The acronym ADPIE is seldom mentioned outside the context of nursing school. If after this continuing education activity, you ask a nurse to collaborate on ADPIE, you might receive a less-than-friendly response. Nurses in the wild rarely plan care by literally defining each element of ADPIE. Rather, ADPIE is a cognitive process in the background of the nurse’s mind. As such, many nurses believe ADPIE to be the busy work of nursing school and inapplicable to nursing practice.

However, while some nurses assert that ADPIE is not used in the profession, it is. In fact, these elements are part of the American Nurses Association’s Scope of Nursing Practice. Even if a nurse doesn’t conscientiously analyze each letter of the formula when providing patient care, the principles remain the framework of nursing practice.4,8

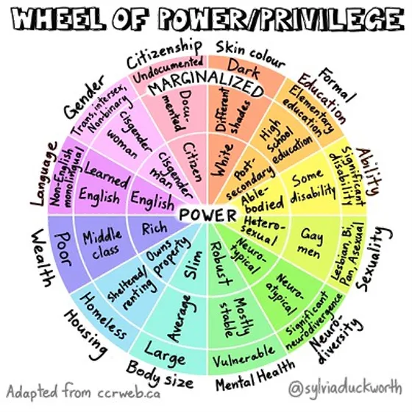

THE PHARMACY TEAM’S SLICE OF PIE: HOW TO COLLABORATE

RNs are trained to view patients holistically, connecting the dots between multiple aspects of a patient’s status and medical history.4,8 Every dot is an input to the care plan and a piece of the puzzle the pharmacy team might need to know.

Furthermore, RNs work to establish an environment where patients feel open to sharing.4 Hence, the RN might have information that’s valuable to the rest of the team.

A patient who reveals he is unhoused might not have a safe place to store prescribed narcotics. If a patient shares that she suffers from bulimia nervosa, the provider and pharmacist will need to reconsider certain therapies. These include QT-prolonging tricyclic antidepressants, drugs that increase weight or appetite (some antidepressants), and bupropion, which lowers the seizure threshold.54

What a nurse can learn from assessment that might be valuable to the pharmacy team is practically limitless. Following are some examples:

- Comorbidities—gastroesophageal reflux disease is a contraindication for many drugs.

- Dietary habits—if the patient practices fasting, this affects drugs he must take with food.

- Acute changes—the sudden onset of severe nausea calls for a change in route of administration for oral prescriptions.

- Sleep cycles—some therapies affect or are administered based on sleep/wake cycles, which the RN observes.

- Adverse effects and side effects—the nurse can keep an eye open for signs and a listening ear open for symptoms.

This list paints the picture that the RN has loads of useful information. Consider this PRO TIP: Talk to the nurses! They are the constant set of eyes on the patient. They are the patient’s interviewer, day and night.

If you know of a common issue with a drug, such as its tendency to affect appetite, ask the RN if the patient’s eating habits have changed. Maybe you attended a seminar and learned about a potential drug-drug interaction recently uncovered. If this is relevant to your patient, share this information with the nurse, and ask him to observe for the interaction. Attend the nurse’s rounds if you can. ADPIE presents multiple ways to get involved!

If you’re not sure where to start or aren’t comfortable bringing up ADPIE as a springboard, there’s a simpler way in. Introduce yourself to the RN (in person if possible) and state your objective plainly: “I’d like to collaborate!” This fulfills multiple purposes:

- The RN receives the clear message that you want to collaborate—she won’t need to infer your objective from your actions.

- The RN understands your goal as intended. Otherwise, the RN might mistake your sudden interest for mistrust in his competence.

- Owing to the previous point, an RN who understands your wish to collaborate will realize that you welcome her data and opinions.

If you’re stuck on starting this conversation, be even more direct: “I did a continuing education activity last week that was all about collaborating with RNs. I want to give it a try. Can we discuss what you and I can learn from each other about our patients and how to incorporate that in our day to day?”

Still looking for another nudge? Consider setting yourself a SMART goal! Example: Introduce myself to the day-shift RNs and explain my intention to collaborate by the end of next week.

By the way, if you work with facilities with multiple shifts, make sure to visit each shift if possible. Evening and night shift personnel frequently feel neglected and forgotten, so meeting them personally shows that you acknowledge and value their work. And if you really want to win the nurse team over, maybe even show up with pie!

Further Opportunities for Collaboration

The previous section focuses on partnering with the RN organically within ADPIE, but you’re not limited to this sphere. Keep your antenna up for situations pointing to more complex issues that warrant combining forces.

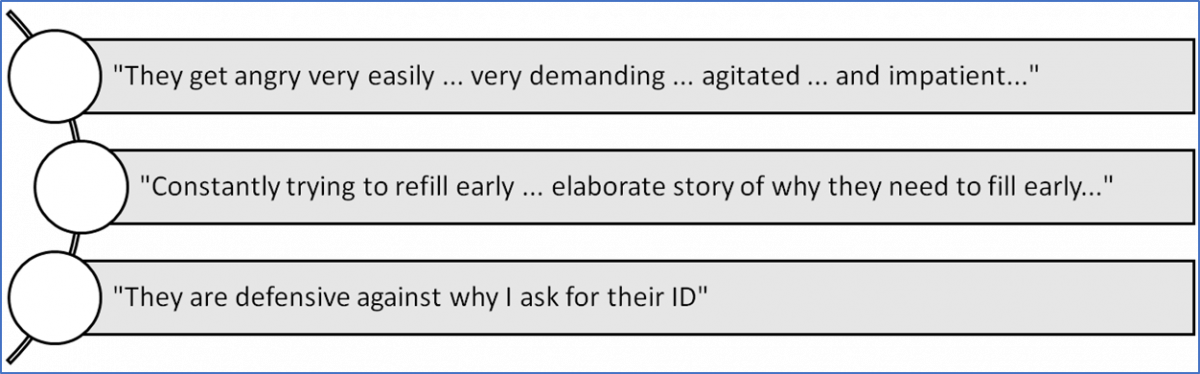

Community pharmacists can detect misuse by monitoring prescription activity. Teamwork is in order if the nature of the facility where a given patient receives care involves repeated or long-term visits. In other words, if the RN will see the patient again—such as at a family physician’s office—he will establish a database of assessment data over time on this patient.

Subsequent communication with the RN is a two-way street. The pharmacist can advise the RN to be cognizant of potential misuse, or she can ask the RN about assessment findings. For instance, the pharmacist could learn through the RN that a family member might be stealing the patient’s prescriptions.

Pharmacy technicians can capture medication history when patients transfer facilities. A geriatric patient transferring between long-term care and critical care, for example, is likely to have an abundant list of prescriptions at both facilities. This implicates a high likelihood of polypharmacy, interactions, and toxic levels of components such as aspirin and acetaminophen. Plus, polypharmacy is a nursing diagnosis, which means by definition that the nurse can intervene.51 It’s a multidisciplinary problem—time to collaborate!

Does your patient need assistance communicating due to factors such as age, sensory deficit, or cognitive impairment? Work with the nurse to ensure the right pain scale is being used and that the patient has a means of communicating adverse effects.

CONCLUSION

Every member of the healthcare team has a distinct role. Nurses are no exception—they continuously assess patients by physical and verbal means and establish and continually revise care plans accordingly. Knowing each team member’s function is crucial to maximally effective collaboration. In the face of the opioid crisis, healthcare providers should capture every opportunity for better patient care, particularly in pain management. This includes incorporating nonpharmacologic pain control strategies and intelligently selecting pharmacologic methods. Regardless of the modalities chosen, abundant opportunity for coordination between the nurse and pharmacy teams exists. This is especially true when the pharmacist and pharmacy technician understand the principles behind the nursing practice and care planning, summarized by the acronym ADPIE. Marrying the concepts of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain control therapies with nursing care plans enables the pharmacy team to collaborate effectively for patients’ pain relief.