Learning Objectives

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

| · Describe the principles of palliative and hospice care |

| · Discuss treatment options to manage the end-of-life symptoms of air hunger and/or pain |

| · Calculate appropriate opioid dose-equivalents |

| · Recognize risks of diversion in the hospice setting |

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to

| · Describe the principles of palliative and hospice care |

| · Identify treatment options to manage the end-of-life symptoms of air hunger and/or pain |

| · Recognize risks of diversion in the hospice setting |

Release Date:

Release Date: September 3, 2025

Expiration Date: September 3, 2028

Course Fee

Pharmacists - $7

Technicians - $4

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-25-054-H08-P

Pharmacy Technician: 0009-0000-25-054-H08-T

Session Codes

Pharmacist: 22YC48-JKV62

Pharmacy Technician: 22YC48-XTY88

Accreditation Hours

2.0 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-25-054-H08-P/T will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Lisa E. Ruohoniemi, PharmD

Clinical Staff Pharmacist

HCA Healthcare LewisGale Hospital Montgomery

Blacksburg, VA

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Dr. Ruohoniemi has no relationship with ineligible companies and therefore has nothing to disclose.

ABSTRACT

Palliative and hospice care mitigate suffering and maintain patients’ dignity and comfort throughout the course of disease. Palliative and hospice care are different, but related. Patients become eligible for hospice care (an insurance benefit) when they no longer wish to pursue curative therapies, and their prognosis is 6 months of life expectancy or less. Hospice teams practice comfort care. Palliative care is available throughout a patient’s life-threatening disease. Towards life’s end, many patients experience pain and/or dyspnea (e.g., shortness of breath or air hunger). Opioids can alleviate these symptoms, but healthcare professionals face many clinical decisions when choosing a pain control regimen. They use equianalgesic dosing to convert patients from one opioid formulation to another. Particular issues arise in different care settings; practitioners in hospitals must manage pain crises, while those in transitional facilities, such as hospice houses offering respite care, must select appropriate routes of administration. Patients may have misconceptions about medications in hospice; being well-versed in opioids’ uses and side effects allays these concerns. Palliative/hospice care should always put the patient’s comfort first.

CONTENT

Content

INTRODUCTION

In 2020, The World Health Organization estimated that 40 million people need palliative care each year.1 Palliative care is “an interdisciplinary care delivery system designed to anticipate, prevent, and manage physical, psychological, social, and spiritual suffering to optimize quality of life for patients, their families, and caregivers.”2 As patients near the end of their lives, they may elect to pursue hospice care with a greater focus on maintaining their dignity and comfort.3 Such care is available in a variety of settings, including acute care hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, hospice houses, and the patient’s own home.4

A misconception—that palliative care is relevant only at the end of a patient’s life—is common. All patients contending with serious illnesses can benefit from palliative services.5 Patients with chronic diseases may choose to pursue both active treatment of their condition and palliative care for symptom management, working with a specialized, interdisciplinary team of healthcare professionals.4 This team collaborates with patients and their families to identify the patient’s treatment priorities and work to eliminate suffering throughout the course of the disease.6

Pharmacists are important members of the palliative care team and are involved with developing and implementing an individualized treatment plan for each patient.7 These plans “[require] specific patient goals with pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management to improve quality of life while reducing costs and unnecessary medications.”7 Pharmacists provide valuable input to prescribers regarding medication selection, dosing recommendations, and nontraditional routes of administration, all of which will vary from patient to patient.6,7

Pharmacy staff also have the opportunity to educate patients and their families directly regarding appropriate medication use and side effect management. Additionally, they may dispel myths about opioid use in palliative and hospice care and help identify allergies and adverse reactions. They are also well-placed to identify instances of medication diversion in both inpatient and outpatient settings.6-8

Healthcare providers should feel comfortable managing patients pursuing palliative and hospice care, recognizing that medication is but one part of the care provided. The focus should be squarely on patients and their families and the goal of alleviating their suffering, no matter the stage of their disease.

PRINCIPLES OF PALLIATIVE/HOSPICE CARE

Palliative care is comprehensive in its management of the patient. According to the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care, it9

- Provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

- Affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

- Integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care

- Offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement

Knowing that palliative care is not withdrawal or withholding of care is critical; it is simply a treatment with a different goal in mind: in this case, comfort, whether the patient is seeking cure or not. Palliative care comprises many components aside from medication; these may include varied offerings like mental health counseling, art therapy, and pastoral care, among others. All hospice care is palliative in nature, but not all palliative care is hospice care.11

Table 1 compares both types of care.

| Table 1. Characteristics of Palliative vs. Hospice Services12-14 | ||

| Palliative Services | Hospice Services | |

| When is it implemented? | As early as diagnosis; at any stage of disease | 6-month life expectancy or less |

| Is it used along with active treatment/life-prolonging measures? | Yes | No |

| Where is it offered? | Usually an acute care facility or outpatient clinic, but may also be offered in nursing home, hospice house, or private residence | Various settings, including an acute care facility, nursing home, hospice house, private residence |

| Are psychosocial/emotional support services offered? | Yes | Yes |

| Does it involve treatment, including medication, for symptom relief? | Yes | Yes |

Opioids in End-of-Life Care: Management of Pain and/or Dyspnea

Pain and dyspnea (also known as shortness of breath or air hunger) are common symptoms at the end of life.15,16 This holds true even for patients without a respiratory causative diagnosis such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; patients with cancer (70%), AIDS (11% to 62%) and other terminal illnesses also experience difficulty breathing at the end of life.17 And in one study of 988 terminally ill patients, half experienced moderate or severe pain.18 Easing these symptoms reduces patient and family distress during the active dying process.

OPIOID PHARMACOLOGY

Opioids are the mainstay of therapy for pain and dyspnea in end-of-life care due to their multimodal mechanism of action.15 In the body, they bind to three different opioid receptor subtypes, known as mu-, kappa-, and delta-receptors.16,19

- Mu (μ) are responsible for analgesia, sedation, gastrointestinal distress, respiratory depression, euphoria, dependence

- Kappa (κ) are responsible for analgesia, sedation, dyspnea and respiratory distress, euphoria

- Delta (δ) are responsible for analgesia and spinal analgesia

These receptors are present in pain pathways in the central nervous system; by binding to them, opioids inhibit stimulatory neurotransmitters that conduct pain signals to the brain.20

Dyspnea’s exact mechanism at the end of life is poorly understood; however, opioids’ ability to mitigate shortness of breath is possibly due to their secondary effects. Opioids may alter a patient’s ventilatory response to carbon dioxide, ease hypoxia, change inspiratory flow resistive loading, and improve oxygen consumption.21 In other words, opioids decrease respiratory drive, alter the perception of breathlessness, change peripheral opioid receptors’ activity in the lung, and decrease anxiety, all of which contribute to the sensation of dyspnea.22 Patients and caregivers perceive the shortness of breath as anxiety and often reach for the benzodiazepines to relieve this discomfort. However, opioids are the drug of first choice for dyspnea and may provide relief of the underlying cause thereby minimizing anxiety.

Selecting an Opioid

Consideration of patient-specific factors should guide the healthcare provider’s selection of opioid for pain and dyspnea.23,24 Opioids’ pharmacokinetic profiles differ, sometimes substantially, from one medication to another. 25 Additionally, patients’ unique genetic identities may influence an opioid’s bioavailability, metabolism, and the patient’s physical response to the opioid.23 Table 2 lists some questions clinicians should ask themselves when deciding on a pain management regimen.

| Table 2. Clinical Considerations in the Selection of Opioids for a Patient Receiving Palliative Care25 | |

| Consideration | Example |

| What kind of pain am I treating? | Breakthrough vs. chronic, neuropathic vs. skeletomuscular

|

| What are the patient’s needs and goals? | Some patients may prioritize total pain relief; others may tolerate more pain in order to be less sedated

|

| Is it practical and easy to administer the ordered dose? | Order reasonable, whole-number doses at even dosing intervals, i.e., avoid oxycodone 3 mg by mouth every 5 hours |

| Is the patient likely to derive meaningful relief from this regimen? | Consider renal and hepatic function, body composition, feasible routes of administration, drug interactions, etc. |

Common Opioids Used in Palliative and Hospice Settings

Opioids are classified into four groups based on their chemical structure:

- Phenanthrenes

- Benzomorphans

- Phenylpiperidines

- Diphenylheptanes

The importance of these chemical structures will be discussed in the “Dispelling Common Hospice Myths” section.

Table 3 describes opioids commonly used in the palliative and hospice settings, and some of their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics.

| Table 3. Opioids* Commonly Used in the Palliative and Hospice Settings15,16,26 | |

| Opioid | Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Characteristics |

| Morphine (Avinza, Kadian, MS Contin, Duramorph, MSIR) | Phenanthrene HydrophilicMetabolism: glucuronidation Highly protein-bound Mean elimination half-life: 2 hours |

| Hydrocodone (Norco, Hycet, Vicodin, Lorcet, Lortab)

Note: only available in combination with non-opioid analgesics |

Phenanthrene Metabolism: CYP2D6 enzyme Mean elimination half-life: 2.5-4 hours |

| Oxycodone (Oxycontin, OxyIR, Roxicodone, XTAMPZA, Percocet)

Note: available on its own and in combination with non-opioid analgesics |

Phenanthrene Metabolism: CYP2D6, CYP3A4 enzymes Mean elimination half-life: 2.5-3 hours |

| Hydromorphone (Dilaudid, Exalgo) | Phenanthrene HydrophilicMetabolism: glucuronidation Mean elimination half-life: 2-3 hours |

| Fentanyl | Piperidine Metabolism: CYP3A4 enzyme |

| Tramadol (Ultram, Ryzolt) | Mu-opioid agonist

Metabolism: CYP2B6, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 enzymes Mean elimination half-life: 6-8 hours |

*Note: Methadone, a diphenylheptane synthetic opioid derivative, is also commonly used for palliative and hospice patients with severe pain who are not opioid-naïve. Its metabolism is non-linear and its dosing is complicated; this continuing education activity will not discuss methadone in detail.26

Renal and Hepatic Dysfunction

Renal and hepatic metabolism affects multiple opioids. Table 4 discusses the use of these medications in instances of advanced kidney or liver disease and identifies drugs that should be avoided in these populations. In patients with impaired metabolism of opioids, providers should select the lowest effective dose and titrate cautiously to effect.

| Table 4. Opioids in Organ Impairment15,27,28,29 |

| Safe | Use with Caution | Avoid |

| Renal Impairment | ||

| Hydromorphone

Methadone Fentanyl |

Hydrocodone

Oxycodone Tramadol |

Morphine |

| Hepatic Impairment | ||

| Hydromorphone

Fentanyl Morphine |

Hydrocodone

Oxycodone Tramadol |

Methadone |

EQUIANALGESIC DOSE CONVERSIONS

It is common in palliative and hospice care for patients to require multiple opioids for symptom management.30 As patients transition from the acute inpatient setting to outpatient care, clinicians should also consider converting parenteral opioid doses to oral forms whenever possible.31,32 This aids patient comfort and eases administration, particularly when a caregiver, rather than a medical professional, is responsible for the patient’s medication management.

Equianalgesia refers to various opioids’ analgesic doses that are estimated to provide the same pain relief.33 Equianalgesic dose conversion charts and calculators are widely available as tools to help clinicians determine appropriate opioid dosages for patients; however, pharmacists should be aware that all conversion charts are approximations and are only to be used as guides.34,35 Different sources may have slight variances in their conversion factors.36 Clinicians may use these charts as a way to double-check their arithmetic by comparing the doses calculated using different tables. Table 5 is one example of an equianalgesic dose conversion chart. Additionally, because of patient-specific factors, the appropriate dose for a patient may not always be the one calculated based on a standardized ratio. There is no substitute for sound clinical judgment!

| Table 5. Equianalgesic Opioid Dose Conversions 15,37 | |||

| Drug | Oral Dose | Parenteral Dose | Conversion Ratio (to oral morphine) |

| Morphine | 30 mg | 10 mg | 3:1 |

| Oxycodone | 20 mg | -- | 2:3 |

| Hydrocodone | 20 mg | -- | 2:3 |

| Hydromorphone | 7 mg | 1.5 mg | Oral hydromorphone: 1:4

Parenteral hydromorphone: 1:20 |

| To convert from one parenteral or oral opioid dose to another, follow these steps3,33,37,38:

1. Determine the total daily dose of current regimen in morphine equivalents a. Add all doses of opioids the patient receives over a 24-hour period b. Calculate equianalgesic morphine dose by multiplying the dose of the opioid you are switching from by the conversion factor*

2. Reduce the total daily dose of the new opioid by 25%-50% for incomplete cross tolerance*

3. Select the new dosing interval, accounting for short- and long-acting dosage forms a. Convert the total daily dose (TDD) of the old opioid to the new opioid using a dose conversion chart b. Determine the breakthrough/as-needed (PRN) dose of the new opioid by calculating 10-15% of the TDD for each PRN dose

Utilize short dosing intervals (every 1-3 hours) for PRN pain control in hospice/palliative care |

| * Incomplete Cross Tolerance

On occasion, clinicians may need to switch patients from one opioid to another when a patient develops tolerance (decreased pharmacologic response pursuant to repeated or prolonged drug exposure).39 Incomplete cross tolerance occurs when patients have developed some level of tolerance to opioids with pharmacologically similar structures. However, the extent of this tolerance varies, and clinicians may unintentionally overdose patients by over-estimating their ability to handle an equianalgesic dose of a new opioid.39 To account for this phenomenon, clinicians should consider reducing the dose of the new opioid (i.e., the one you are switching to) by 25% to 50%.39,40 Many patients experience decreased analgesia from their pain regimen over time and benefit from opioid rotation. Opioid rotation is the process of switching the patient to a novel opioid not currently part of their pain management plan.33 Of note, clinicians may also consider opioid rotation if patients experience intolerable side effects from a drug within the same class.

Example 1: Converting from the parenteral to the oral form of the same drug Convert a patient on an IV morphine drip at 1 mg/hr, to an oral regimen or sustained-release morphine.

Example 2: Converting from the parenteral form of one drug to the oral form of another drug Convert hydromorphone 1 mg IV every 2 hours to a pain control regimen involving oxycodone extended release (ER) and oxycodone immediate release (IR) for breakthrough pain.

|

Note that healthcare providers still need to use good clinical judgment when determining the final recommendation; there is no standardized dosing interval for short-acting opioids, although long-acting opioids are not given more frequently than every eight hours.41,42

ROUTE-SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS

Intensol Formulations

Oral opioids are the formulation of choice for most patients pursuing palliative and hospice care.43 At the end of life, many patients become frail and lose muscle tone, resulting in decreased swallowing ability; however, many of the most common medications used in hospice, including morphine, come in a highly concentrated intensol formulation. These concentrated products deliver sizable doses in very small liquid volumes.44

Even in cases of severe pain and advanced illness, oral morphine remains an effective and suitable option; while inpatient facilities sometimes use morphine infusions, infusions are often unnecessary for patients at the end of life.44,45 To be most effective, clinicians should prescribe and administer morphine around the clock at consistent intervals to ensure steady pain control.45

Concentrated morphine solution (Roxanol) is available in a 20 mg/1 mL solution, allowing effective delivery of the medication even in patients unable to swallow.46 In this situation, the caregiver can prop the patient’s body to a 30-degree angle and instill up to 1 mL of the intensol solution into the buccal (cheek) area. This area serves as a “reservoir” for the medication as it slowly trickles down into the gastrointestinal tract where it is absorbed.44

Transdermal Fentanyl Patches

Transdermal fentanyl patches may be a reasonable option for opioid-tolerant patients requiring around-the-clock pain control. Clinicians, however, should never employ transdermal fentanyl for immediate or intermittent pain relief as it takes approximately 24 hours (up to as much as 48 hours) for serum fentanyl concentrations to reach a constant state.47 Package labeling also specifies that prescribers should only use fentanyl patches in patients who

- are already receiving opioid therapy

- have developed opioid tolerance, and

- are receiving a total daily dose at least equivalent to [fentanyl] 25 mcg/hr.47

Opioid tolerance, for the purpose of using a fentanyl patch, is defined as having been on at least 60 mg of morphine or its dosage equivalent daily for at least a week.47

Proper application of the fentanyl patch is necessary to ensure optimal pain relief and reduce the likelihood of adverse reactions. Clinicians should communicate the following to patients prescribed transdermal fentanyl patches47:

- Each new fentanyl patch should be applied to a different skin site after removal of the previous one

- The patch need not be applied to the area of discomfort or pain

- Patients may tape the edges of the patch with first aid tape

- If the patch falls off before 72 hours, dispose of it by folding it in half and flushing down the toilet

- Fentanyl patches must never be cut

- Never place a heating pad over a fentanyl patch

Do not escalate fentanyl patch doses more frequently than every two to three days. When a patch is first applied, serum fentanyl concentrations will increase with the first few applications.47 Following several rounds of patch applications, serum concentrations eventually reach steady state, meaning that it is difficult to measure a patient’s pain relief accurately during the initiation of a new transdermal fentanyl dose.47 Premature dose escalation may lead to overdose.

Additionally, body composition is an important clinical consideration when using transdermal fentanyl. This drug’s absorption is related to a patient’s body fat composition as fentanyl is lipophilic. Patients who are cachectic (wasting physically with weight and muscle mass loss due to disease) or suffer from profuse sweating, as many cancer patients do, will derive minimal benefit from transdermal fentanyl patches.44,48 Heat will increase the absorption of fentanyl from the patch, so heating pads must never be applied directly over the patch and patients with fever should have their patch removed and an alternate dosage form should be used.

It is appropriate to use fentanyl patches in conjunction with opioids given by other routes of administration. Judicious use of the patches may reduce the need for breakthrough pain doses by providing more consistent drug delivery over the 72-hour application period. Levy’s Rule (See Figure 1) provides the conversion factor to calculate equianalgesic transdermal fentanyl doses based on a patient’s total daily dose of oral morphine equivalents.49

FIGURE 1

|

Levy’s Rule: Fentanyl patch dose (in mcg) = half of the TDD oral morphine

|

Managing a Pain Crisis

A pain crisis is a situation in which a patient’s pain is severe and uncontrolled, causing the patient, family, or both severe distress; the pain crisis may be sudden in onset or the result of worsening chronic pain.25 Clinicians should address this rapidly-escalating, uncontrolled pain promptly and aggressively. When patients are in pain crises, members of the treatment team, including nurses, pharmacists, and physicians, must work together to monitor their responses to opioid administration closely and make adjustments accordingly.50

Clinicians should double the dose of the immediate-acting opioid every twenty minutes until the patient’s pain is controlled and conduct a review of the pain management plan thereafter to determine if dosage or administration frequency need to be changed.25 Opioids have no maximum dosage limit; particularly in the palliative care setting, doses must be titrated to an appropriate level of pain relief that ensures a satisfactory result.

PAUSE AND PONDER: A patient is in pain crisis. You recommend doubling her dose of intravenous hydromorphone every 20 minutes, but her new nurse is nervous about increasing her dose so aggressively. How do you explain the treatment plan and alleviate his concern?

DISPELLING COMMON HOSPICE MYTHS

For many patients and their families, hospice is a difficult term to face at first. Pharmacists are in a unique position, both in the inpatient and outpatient settings, to speak to them as medication experts.7 Patients may express hesitation around opioid use related to a variety of factors.3,51 One study (N = 496) explored terminally-ill patients’ reasons for declining pain management; patients indicated that they feared addiction, found mental or physical side effects unwelcome, and resented the burden of medication in terms of number of doses.18 Table 6 lists some common misconceptions about opioid use in hospice care and suggests responses pharmacists can use to educate patients about these medications’ place in palliative care.

| Table 6. Myths and Facts About Opioid Use in Hospice Care3,52-55 | |

| Myth | Fact |

| “Opioids will make me die faster” | When used appropriately, opioids will not hasten death and can help relieve breathing discomfort many patients experience at the end of life. |

| “I will get addicted to opioids” | Patients may develop a tolerance to opioids, which occurs when they experience decreased pain relief compared to when they started taking the medication. This is a result of the way the drug works in the body. Patients may need higher doses to achieve the same effect. This is different from addiction. Addiction is a disease that involves a person’s repeated use of a drug despite experiencing negative consequences. Needing higher doses of an opioid does not mean a person is addicted. |

| “Going on hospice care and taking opioids means giving up” | Hospice provides care tailored to a patient’s dignity, comfort, and quality of life. It is not the same as withdrawing medical treatment; in fact, a multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals manages patients in hospice. Medications, like opioids, are only one component of the care hospice patients receive. |

| “I get too constipated when I take opioids” | Constipation is a common opioid side effect that does not resolve over time, so clinicians need to prescribe appropriate laxatives for patients on opioids. Constipation in itself is not a contraindication to the use of opioids in palliative/hospice care. |

Allergy vs “Allergy”

Another common misconception patients have regarding opioid use relates to allergies, as many opioid side effects mimic symptoms of true allergic reactions.56 Palliative care clinicians need to be able to differentiate between a true allergy and an adverse reaction to determine appropriate pain regimens for patients safely.

True drug allergies, also known as type I hypersensitivity reactions, are due to immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated release of antibodies against the offending agent.57 This reaction, in its severest form presenting as anaphylaxis, occurs in less than 2% of patients.56,57 While the gold standard for identifying a true drug allergy is drug provocation testing, achieved by exposing a patient to small doses of suspected drugs and monitoring for a reaction, clinicians rarely order drug provocation testing in practice and it is even less relevant in the hospice population.58

In contrast to drug allergies, adverse reactions (see Table 7) are known or expected responses, different from the intended therapeutic effect, to a medication.59 Such adverse reactions are commonly due to the parent opioid’s active metabolites.16

| Table 7. Management of Common Opioid Adverse Reactions56,62 | ||

| Adverse Reaction | Do patients develop tolerance to this adverse reaction? | Management |

| Nausea/vomiting | Yes | May recommend use of prophylactic antiemetics (i.e., ondansetron, metoclopramide) |

| Constipation | No | Routinely recommend concomitant use of a stool softener (i.e., psyllium or docusate) or stimulant laxative (i.e., senna, bisacodyl) |

| Itching | Yes | May recommend use of prophylactic H1 or H2 histamine antagonist (i.e., diphenhydramine, loratadine, famotidine) |

Patients may also demonstrate pseudo-allergy to an opioid, which is an adverse reaction that appears to mimic a true allergy but is unaffected by IgE.56 These may include mild itching, skin redness, or bronchospasm but do not necessarily indicate an allergic reaction.60 Instead, they are more commonly due to a histamine-mediated response.60 Histamine release is related to the opioid’s potency; the more potent the opioid, the less histamine release and the lower the likelihood of a histamine-mediated reaction.

If a patient demonstrates any one of these symptoms or develops several that are mild in severity, it does not necessarily signal the patient has an immune-related allergy to opioids. Similarly, histamine-meditated adverse reactions do not mean opioids as a class are contraindicated for use in the affected patient. Clinicians in this scenario can opt to pre-medicate the patient with antihistamines or steroids before administering an opioid for a few days until the effect is minimized.60 They may also consider an alternative opioid in a different pharmacologic opioid class which may be more tolerable.60

PAUSE AND PONDER: What questions would you ask patients to assess whether they are experiencing an allergy versus a side effect?

Cross-reactivity can occur when a chemical component of one medication is like that in another, resulting in an allergic reaction to both drugs.61 Understanding opioids’ chemical structures (see Table 8) allows clinicians to determine risk of cross-reactivity when they are concerned about a true allergy. Cross-reactivity may occur within the same class; for example, a patient with a true allergy to codeine should not take oxycodone. However, it is reasonable for a patient with an allergy to a drug in one class of opioids to take a medication from another class.62 The risk for cross-reactivity in this situation is low, but if the patient has a true allergic reaction, they should only take an opioid from another class under supervision of a healthcare professional until allergy to that product is ruled out.62

| Table 8. Chemical Classes of Opioids16 | |||

| Phenanthrenes | Benzomorphans | Phenylpiperidines | Diphenylheptanes |

| Buprenorphine

Butorphanol Codeine Hydromorphone Morphine Nalbuphine Oxycodone |

Pentazocine | Alfentanil

Fentanyl Meperidine Sufentanil |

Methadone |

DIVERSION

Drug diversion is defined as “a criminal act or deviation that removes a prescription drug from its intended path from the manufacturer to the intended patient.”63 The hospice setting is not immune to the risk of diversion. Given the estimate that more than 90% of hospice and palliative care patients receive a controlled pain medication, diversion is a very real concern.30 One survey of 371 hospices revealed that 31% of facilities interviewed reported at least one case of confirmed diversion in the past quarter.64

Palliative care presents unique diversion issues because it is often delivered in the patient’s home, rather than a facility. The home environment, while often the preferred site of care, is less closely monitored and controlled than in an inpatient setting, making it a susceptible site of opioid diversion.65 Caregivers, family members, healthcare providers, and patients themselves may all divert opioids.66

Identifying diversion

Providers should be able to identify instances of possible diversion and take reasonable steps to prevent it from happening.67 State prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) are one such way to monitor patient’s access to opioids.68 These programs vary from state to state, but all allow authorized providers to review a patient’s controlled substance fill history.68 Practitioners should make it a habit to review their state’s PDMP prior to filling a prescription for a controlled substance to determine whether a patient may seek out multiple prescribers or visit different pharmacies. Such behavior does not always indicate drug misuse or diversion but should prompt the pharmacist to identify any risky activity. Other common “red flags” that may signal a person is diverting medication:

□ Frequent or early refill requests from patient or caregiver

□ Inaccurate or missing record-keeping by pharmacy or hospice agency

□ Noncommunicative patients who appear to always be in severe pain/distress

□ Impaired caregivers, including both family members and home health staff

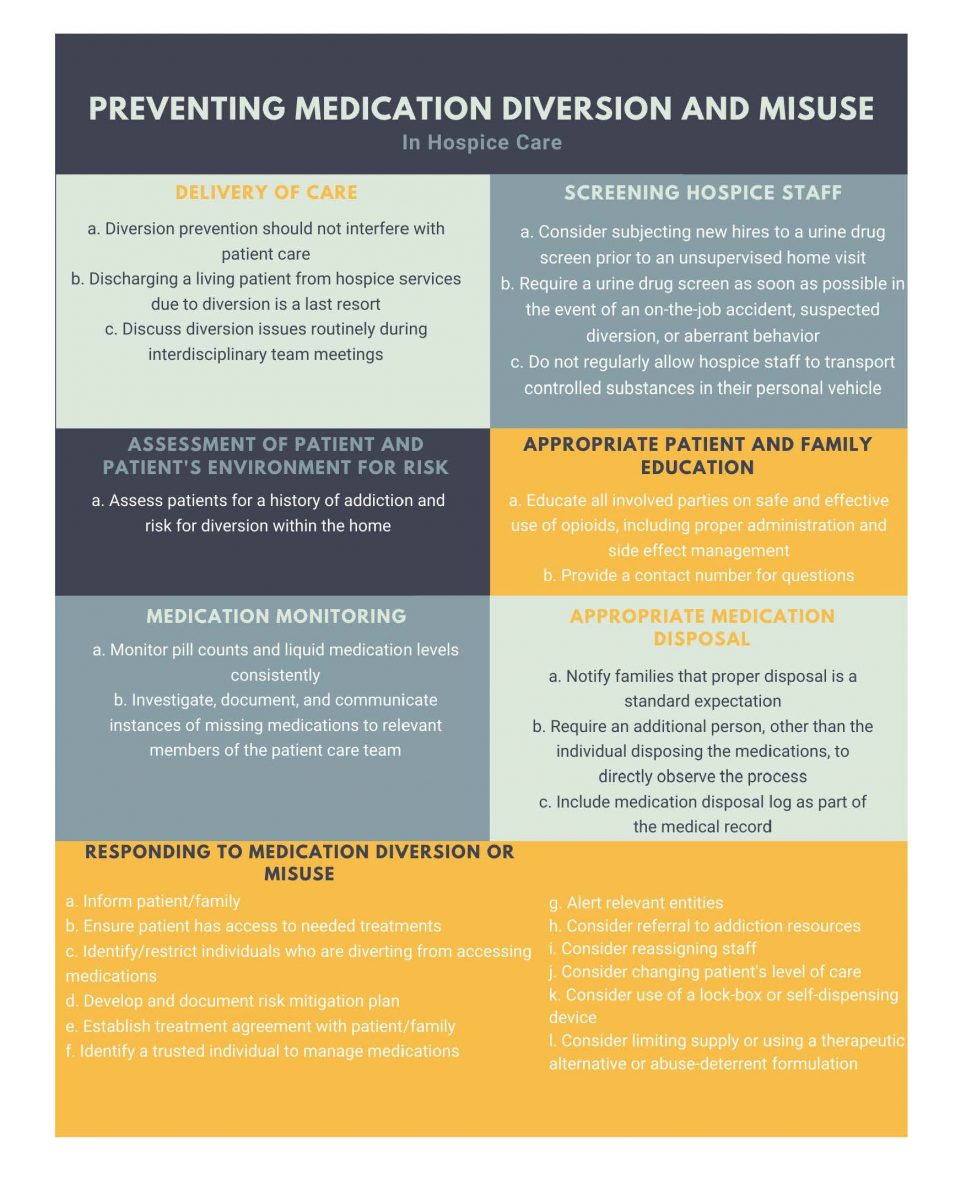

The University of Maryland, Baltimore, in conjunction with the Hospice Foundation of America, has developed 15 recommendations for preventing medication diversion and misuse in hospice care.69 These include recommendations related to several care areas featured in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2

Hospice Prescriptions Transmitted by Facsimile

Federal and state laws regulate controlled substances dispensing for hospice patients. Specifically, prescribers may fax prescriptions for C-II medications to retail pharmacies without needing to subsequently furnish a hard copy as they would for a non-hospice patient.70 The federal law regarding faxing C-II prescriptions for hospice patients states that “a prescription prepared in accordance with §1306.05 written for a Schedule II narcotic substance for a patient enrolled in a hospice care program certified and/or paid for by Medicare under Title XVIII or a hospice program which is licensed by the state may be transmitted by the practitioner or the practitioner's agent to the dispensing pharmacy by facsimile. The practitioner or the practitioner's agent will note on the prescription that the patient is a hospice patient. The facsimile serves as the original written prescription for purposes of this paragraph (g) and it shall be maintained in accordance with §1304.04(h).”70 The faxed prescription must indicate that it is for a hospice patient in order to be filled legally—pharmacy teams should make note of this rule and ensure prescribers so annotate prescriptions.

Conclusion

Patients in palliative and hospice care have unique needs. Clinicians should be familiar with how the two types of care differ and their common characteristics. To manage a patient’s pain and dyspnea, healthcare providers should have a solid foundational knowledge of opioid medications and an understanding of how to select and tailor patients’ pain control regimens to their specific needs. There is no treatment algorithm for pain management, just as there is no standardized equianalgesic opioid dose conversion chart. Clinicians must account for patient- and drug-specific factors and use their own judgment when transitioning patients from one opioid to another to ensure adequate pain control. Certain formulations, such as intensol and transdermal patches, also have route-specific considerations. Pharmacists particularly are well-placed to educate other healthcare professionals as well as patients and their caregivers about opioids’ place in palliative/hospice care. They can “myth-bust” common hospice misconceptions, help identify allergies and adverse reactions, and inform treatment decisions related to acute situations (like pain crises) and transitions from inpatient to outpatient settings. They can also be closely involved in monitoring, documenting, and preventing issues related to medication diversion. Drug therapy is a significant component of palliative/hospice care. It requires a thorough and sensitive understanding by medical staff so that patients derive maximum benefit from it as they approach the end of their lives. Alleviation of suffering, and the protection of a patient’s dignity, should be at the core of any medication decisions made for these patients.

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

Pain Management in Palliative Care

25-054

Learning Objectives

• Describe the principles of palliative and hospice care

• Discuss treatment options to manage the end-of-life symptoms of air hunger and/or pain

• Calculate appropriate opioid dose-equivalents

• Recognize risks of diversion in the hospice setting

*

1. Which of the following is TRUE of palliative care?

a. It can hasten a patient’s death by using high doses of opioids and benzodiazepines

b. It is intended for patients with a life expectancy of six months or less

c. It is intended for any patient with a chronic disease, regardless of stage of illness

*

2. Your pharmacy receives a faxed prescription for KL. It has all the valid components of a legal prescription but does not specify “hospice patient” on it. Her family member confirms that KL is in fact pursuing hospice care. What should your next step be?

a. Fill the prescription as-is, indicating on the back of the fax that it is for a hospice patient; pharmacist documentation is sufficient

b. Call the physician’s office to request the prescription be re-transmitted with the necessary information documented on it

c. Contact your local DEA office to report your suspicion of medication diversion, as the prescription is a counterfeit

*

3. The hospitalist is preparing to discharge patient NM who has previously been on IV hydromorphone 1 mg q4h PRN, averaging four doses per day. He would like to send NM home on oral oxycodone at the same dosing interval (every four hours). What dose would you recommend?

a. Oxycodone 10 mg by mouth every 4 hours PRN

b. Oxycodone 5 mg by mouth every 4 hours PRN

c. Oxycodone 8.88 mg by mouth four times per day PRN

*

4. Which of the following is a step a home hospice agency could take to prevent diversion?

a. Designate one staff member to witness medication disposal after a patient dies

b. Conduct urine drug screens for new hires prior to an unsupervised home visit

c. Permit hospice staff to transport controlled substances via their personal vehicles

*

5. A man comes in with several prescriptions for his 98-year-old mother. He is concerned that the physician ordered morphine intensol, saying, “She was just in the hospital for pneumonia because she keeps inhaling her food when she eats. Won’t this cause the same problem?” How could you respond?

a. Tell him you will call the physician to have her change the order to morphine 10 mg/5 mL liquid

b. Advise him to crush her extended-release morphine tablets and use a small amount of water to make a paste she can swallow

c. Reassure him that morphine intensol is a concentrated liquid formulation that delivers drug in a very small volume

*

6. Which of the following might lead you to consider the possibility that a family member was diverting controlled substances for a hospice patient?

a. Family member claims patient needs morphine intensol for difficulty breathing, even though the patient isn’t dying from a lung disease

b. Family member provides prescriptions from several providers in different specialties and office locations

c. Family member claims patient needs morphine intensol for pain, even though the patient is on a high dose that should sedate her enough to be comfortable

*

7. Patient RT has advanced lung cancer with metastases to the bone and brain. He comes to your hospital in a pain crisis, as his family has been unable to control his pain with oral medications at home. The hospitalist starts him on hydromorphone 1 mg IV every 5 minutes. RT receives four consecutive doses but is still in excruciating 10/10 pain. What is the best next step to recommend?

a. Double the dose to hydromorphone 2 mg IV every 5 minutes

b. Transition the patient to an equianalgesic dose of oral hydromorphone

c. Initiate an oral long-acting opioid such as extended-release morphine or extended-release oxycodone

*

8. When converting a dose of one opioid to an equianalgesic dose of another, you must reduce your final calculated dose by 25-50%. Why is this?

a. To account for incomplete cross-tolerance and reduce the risk of overdosing the patient with the new opioid

b. To ensure the patient has less potent strengths of an opioid, thereby reducing the likelihood of diversion

c. To make it easier to round your calculated dose to a whole number so patients don’t have to split tablets

*

9. You are a pharmacist in a long-term care facility. You note that one of your patients is a good candidate for a fentanyl patch. He is currently on oxycodone ER 30 mg by mouth BID and oxycodone 5 mg by mouth every four hours as needed. He normally receives three breakthrough doses in a 24 hour-period. What would you recommend?

a. Fentanyl 75 mcg/hour patch, and continue the oxycodone 5 mg by mouth every four hours as needed

b. Fentanyl 100 mcg/hour patch, and discontinue the oxycodone 5 mg by mouth every four hours as needed

c. Fentanyl 50 mcg/hour patch, and continue the oxycodone 5 mg by mouth every four hours as needed

*

10. WN is a 45-year-old male recently diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease). He asks to meet with your hospital’s palliative nurse to discuss symptom management. Which of the following is true?

a. WN should exhaust all treatment options before pursuing palliative care

b. Palliative care can be administered alongside treatment

c. WE cannot explore palliative care until he is estimated to have a 6-month life expectancy or less

*

11. Patient RT has advanced lung cancer with metastases to the bone and brain. He comes to your hospital in a pain crisis, as his family has been unable to control his pain with medication at home. The hospitalist starts him on hydromorphone 1 mg IV every 5 minutes. RT receives four consecutive doses but is still in excruciating pain. What is the next step to recommend?

a. Increase the dose to hydromorphone 2 mg IV every 5 minutes

b. Transition the patient to an equianalgesic dose of oral hydromorphone

c. Initiate a long-acting opioid such as extended-release morphine or extended-release oxycodone

*

12. A pharmacy student uses two different equianalgesic dose conversion charts to calculate an oral hydromorphone dose and comes up with two different calculations: hydromorphone 3 mg by mouth every four hours vs. hydromorphone 4 mg by mouth every four hours. You advise that the 4 mg dose is the better option. Why is this?

a. The patient likely needs a higher dose for better pain control

b. It is a more feasible dose to administer due to the tablet size

c. You calculated the dose to be 4 mg based on the equianalgesic dose conversion chart you used

*

13. In what clinical situation would you consider opioid rotation?

a. In a patient who has developed unbearable constipation, despite taking medications to manage it

b. In a patient who was started on a fentanyl patch one day ago and has yet to show a response

c. In a patient who is responding well to the same pain regimen he has been on for the past two years

*

14. You receive a palliative care consult for a patient with chronic kidney disease who has now also developed acute renal failure. His creatinine clearance in the hospital is currently 24 mL/min. He has been receiving hydromorphone 8 mg by mouth every 6 hours. What is an appropriate recommendation?

a. Continue on the current dose

b. Reduce the dose to 4 mg every 6 hours

c. Increase the dose to 16 mg every 6 hours

*

15. Your patient BB has lost IV access. She was previously receiving morphine 1 mg IV every 2 hours PRN, averaging about 9 doses per day. What would an appropriate oral morphine dose administered every 4 hours PRN be?

a. Morphine 5 mg by mouth every 4 hours PRN

b. Morphine 1.5 mg by mouth every 4 hours PRN

c. Morphine 2.5 mg by mouth every 4 hours PRN

Pharmacy Technician Post Test (for viewing only)

Pain Management in Palliative Care

25-054

Learning Objectives

After completing this CE activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to

• Describe the principles of palliative and hospice care

• Identify treatment options to manage the end-of-life symptoms of air hunger and/or pain

• Recognize risks of diversion in the hospice setting

*

1. Which of the following is TRUE of palliative care?

a. It can hasten a patient’s death by using high doses of opioids and benzodiazepines

b. It is intended for patients with a life expectancy of six months or less

c. It is intended for any patient with a chronic disease, regardless of stage of illness

*

2. Your pharmacy receives a faxed prescription for KL. It has all the valid components of a legal prescription but does not specify “hospice patient” on it. Her family member confirms that KL is in fact pursuing hospice care. What should your next step be?

a. Fill the prescription as-is, indicating on the back of the fax that it is for a hospice patient; pharmacist documentation is sufficient

b. Call the physician’s office to request the prescription be re-transmitted with the necessary information documented on it

c. Contact your local DEA office to report your suspicion of medication diversion, as the prescription is a counterfeit

*

3. A patient comes to your pharmacy with a prescription for methadone. You note she has an allergy to morphine listed in her profile. Which of the following is true?

a. Methadone is not likely to cause the same reaction based on the risk of cross-reactivity

b. You can assume it is probably not a true allergy as many patients report morphine allergy

c. This patient should not take methadone because of her allergy; she will have the same reaction to both

*

4. Which of the following is a step a home hospice agency could take to prevent diversion?

a. Designate one staff member to witness medication disposal after a patient dies

b. Conduct urine drug screens for new hires prior to an unsupervised home visit

c. Permit hospice staff to transport controlled substances via their personal vehicles

*

5. A man comes in with several prescriptions for his 98-year-old mother. He is concerned that the physician ordered morphine intensol, saying, “She was just in the hospital for pneumonia because she keeps inhaling her food when she eats. Won’t this cause the same problem?” How could you respond?

a. Tell him you will call the physician to have her change the order to morphine 10 mg/5 mL liquid

b. Advise him to crush her extended-release morphine tablets and use a small amount of water to make a paste she can swallow

c. Reassure him that morphine intensol is a concentrated liquid formulation that delivers drug in a very small volume

*

6. Which of the following might lead you to consider the possibility that a family member was diverting controlled substances for a hospice patient?

a. Family member claims patient needs morphine intensol for difficulty breathing, even though the patient isn’t dying from a lung disease

b. Family member provides prescriptions from several providers in different specialties and office locations

c. Family member claims patient needs morphine intensol for pain, even though the patient’s high dose that should keep her comfortable

*

7. Your patient YP comes into your pharmacy to fill a prescription for oxycodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg one tablet by mouth every four hours as needed. You see an allergy to morphine listed in his profile. When you ask him about it, he says, “It makes me so sick, I can’t stomach it.” How do you respond?

a. Tell him he should not take the oxycodone/acetaminophen, as he will also be allergic to it and will not be able to tolerate it

b. Tell him all opioids make people nauseous, and he should take morphine rather than oxycodone/acetaminophen since it isn’t a real allergy

c. Confirm with the pharmacist that YP can take the oxycodone/acetaminophen, as nausea is a side effect rather than an allergy

*

8. A patient hands you a prescription. She says, “My doctor had to increase my dose from 1 mg to 2 mg. I’ve been on it for a year but it doesn’t feel like it’s doing anything for me anymore.” What term best describes the phenomenon the patient is experiencing?

a. Tolerance

b. Addiction

c. Medication diversion

*

9. In what way does hospice care differ from palliative care?

a. Hospice uses no active treatment or life-prolonging measures

b. Hospice involves psychosocial and emotional support services

c. Hospice is only provided in a patient’s home or hospital

*

10. WN is a 45-year-old male recently diagnosed with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s Disease). He asks to meet with your hospital’s palliative nurse to discuss symptom management. Which of the following is true?

a. WN should exhaust all treatment options before pursuing palliative care

b. Palliative care can be administered alongside treatment

c. WN cannot explore palliative care until his estimated life expectancy less than 6 month

References

Full List of References

References

References

1. World Health Organization. Palliative Care Key Facts. World Health Organization website. August 5, 2020. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

2. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th edition. Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Accessed April 14, 2021.https://www. nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp.

3. Clary PL, Lawson, P. Pharmacologic pearls for end-of-life care. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(12):1059-1065.

4. National Institute on Aging. What are palliative and hospice care? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. May 17, 2017. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-are-palliative-care-and-hospice-care#:~:text=Palliative%20care%20is%20a%20resource,from%20the%20point%20of%20diagnosis

5. American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Program. Palliative care best practices guidelines. American College of Surgeons website. October 2017. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/palliative_guidelines.ashx

6. Demler, TL. Pharmacist involvement in hospice and palliative care. US Pharm. 2016;41(3):HS2-HS5.

7. Barbee J, Kelley S, Andrews J, Harman A. Palliative care: the role of the pharmacist. Pharm Times. 2016;5(6). https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/palliative-care-the-pharmacists-role

8. Walker KA, Scarpaci L, McPherson ML. Fifty reasons to love your palliative care pharmacist. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27(8):511-513. doi: 10.1177/1049909110371096

9. What is palliative care? International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care website. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://hospicecare.com/what-we-do/publications/getting-started/5-what-is-palliative-care

10. Palliative care or hospice? National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization website. 2019. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/PalliativeCare_VS_Hospice.pdf

11. Palliative care defined. Hospice Foundation of America website. 2018. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://hospicefoundation.org/Hospice-Care/Palliative-Care-Defined

12. Palliative care vs. hospice: what’s the difference? Vitas Healthcare website. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.vitas.com/hospice-and-palliative-care-basics/about-palliative-care/hospice-vs-palliative-care-whats-the-difference

13. Palliative care vs. hospice: similar but different. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Fraud-Prevention/Medicaid-Integrity-Education/Downloads/infograph-PalliativeCare-%5BJune-2015%5D.pdf

14. Healthline. What’s the difference between palliative care and hospice? Healthline website. February 7, 2020. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.healthline.com/health/palliative-care-vs-hospice#how-to-decide

15. Groninger H, Vijayan J. Pharmacologic management of pain at the end of life. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(1):26-32.

16. Trescot AM, Datta S, Lee M, Hansen H. Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S133-S153.

17. Ross DD, Alexander CS. Management of common symptoms in terminally ill patients: part II. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(6):1019-1027

18. Weiss SC, Emanuel LL, Fairclough DL, Emanuel EJ. Understanding the experience of pain in terminally ill patients. Lancet. 2001;357(9265):1311-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04515-3

19. Vallejo R, Barkin RL, Wang VC. Pharmacology of opioids in the treatment of chronic pain syndromes. Pain Physician. 2011;14:E343-E360.

20. Trang T, Al-Hasani R, Salvemini D, Salter MW, Gutstein H, Cahill CM. Pain and poppies: the good, the bad, and the ugly of opioid analgesics. J Neurosci. 2015;35(41):13879-13888. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2711-15.2015

21. Kamal AH, Maguire JM, Wheeler JL, Currow DC, Abernethy AP. Dyspnea review for the palliative care professional: treatment goals and therapeutic options. J Pall Med. 2012;15(1):106-114. doi:10.1089/jpm.2011.0110

22. Mahler, D. Opioids for refractory dyspnea. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2014;7(2):123-135. doi:10.1586/ers.13.5

23. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 140. Cardiff, UK; National Collaborating Centre for Cancer; 2012. National Collaborating Centre for Cancer (UK). Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK115251/ .

24. Barnett M. Alternative opioids to morphine in palliative care: a review of current practice and evidence. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:371-378. doi:10.1136/pmj.77.908.371

25. Moryl, N, Coyle N, Foley KM. Managing an acute pain crisis in a patient with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2008;299(12):1457-1467. doi:10.1001/jama.299.12.1457

26. Brown R, Kraus C, Fleming M, Reddy S. Methadone: applied pharmacology and use as adjunctive treatment in chronic pain. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(949):654-659. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.022988

27. Broadbent A, Khor K, Heaney A. Palliation and chronic renal failure: opioid and other palliative medications- dosage guidelines. Prog Palliat Care. 2013;11(4):183-190. doi: 10.1179/096992603225002627

28. Arnold R, Verrico P, Karnell A, Davison SN. opioid use in renal failure. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin website. March 2020. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/opioid-use-in-renal-failure/

29. Oliverio C, Malone N, Rosielle DA. Opioid use in liver failure. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin website. September 2015. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/opioid-use-in-liver-failure/

30. Cagle, JG. Strategies for detecting, addressing, and preventing drug diversion in hospice and palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(2):360. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.12.023

31. Muller-Busch HC, Lindena G, Kietze K, Woskanjan S. Opioid switch in palliative care, opioid choice by clinical need and opioid availability. Eur J Pain. 2012;9(5):571. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.12.003

32. Portenoy RK, Mehta Z, Ahmed E. Cancer Pain management with opioids: optimizing analgesia. UptoDate website. January 12, 2021. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/cancer-pain-management-with-opioids-optimizing-analgesia

33. Bhatnagar M, Pruskowski J. Opioid Equivalency. StatPearls Publishing;2020. Accessed April 19, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535402/#_NBK535402_pubdet_.

34. Arnold R, Weissman DE. Calculating opioid dose conversions. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin. May 2015. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/calculating-opioid-dose-conversions/

35. Pereira J, Lawlor P, Vigano A, Dorgan M, Bruera E. Equianalgesic dose ratios for opioids: a critical review and proposals for long-term dosing. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(2):672-687. doi:10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00294-9

36. Anderson R, Saiers JH, Abram S, Schlicht C. Accuracy in equianalgesic dosing: conversion dilemmas. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21(5):397-406. doi:10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00271-8

37. Periyakoil V. Equivalency table. Stanford School of Medicine Palliative Care website. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://palliative.stanford.edu/opioid-conversion/opioids/

38. Opioid prescribing guideline resources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. February 2021. Accessed 4/19/2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

39. Dumas EO, Pollack GM. Opioid tolerance development: a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic perspective. AAPS J. 2008;10(4):537-551. doi:10.1208/s12248-008-9056-1

40. Pasternak GW. Preclinical pharmacology and opioid combinations. Pain Med. 2012;13:S4-S11. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01335.x

41. Vallerand AH. The use of long-acting opioids in chronic pain management. Nurs Clin North Am. 2003;38(3):435-445. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6465(02)00094-4.

42. Fine PG, Mahajan G, McPherson ML. Long-acting opioids and short-acting opioids: appropriate use in chronic pain. Pain Med. 2009;10(Supp 2):S79-S88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00666.x

43. Kestenbaum MG, Messersmith S, Vilches AO, et al. Alternative routes to oral opioid administration in palliative care: a review and clinical summary. Pain Med. 2014;15(7):1129-1153. doi:10.1111/pme.12464

44. McPherson, ML, Kim, M, Walker, KA. 50 practical medication tips at end of life. J Support Onc. 2012;10(6):222-229. doi:10.1016/j.suponc.2012.08.002

45. Miller, KE. Continuous infusion of IV morphine for cancer pain. AM Fam Physician. 2003;67(2):416-417.

46. Morphine sulfate solution. Prescribing information. Boehringer Ingelheim; 2012. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://docs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Roxanol/Roxanol.pdf

47. Duragesic. Prescribing information. Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2021. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/DURAGESIC-pi.pdf

48. Clemens KE, Klaschik E. Clinical experience with transdermal and orally administered opioids in palliative care patients- a retrospective study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37(4):302-309. doi:10.1093/jjco/hym017

49. Levy, MH. Pharmacologic treatment of cancer pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(15):1124-1132. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351507

50. Ferrell B, Levy MH, Paice J. Managing pain from advanced cancer in the palliative care setting. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(4):575-581. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.575-581

51. Berger JM, Vadivelu N. Common misconceptions about opioid use for pain management at the end of life. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(5):403-409. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2013.15.5.ecas1-1305

52. Harrod CG, Mahler DA, Selecky PA et al. American College of Chest Physicians consensus statement on the management of dyspnea in patients with advanced lung or heart disease. Chest. 2010;137(3):674-691. doi:10.1378/chest.09-1543

53. The NIDA Blog Team. Tolerance, Dependence, Addiction: What’s the Difference? NIH website. January 12, 2017. Accessed May 4, 2021. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/blog/post/tolerance-dependence-addiction-whats-difference

54. Dispelling Hospice Myths. Hospice Foundation of America website. Accessed May 4, 2021. https://hospicefoundation.org/Hospice-Care/Dispelling-Hospice-Myths

55. Albert RH. End-of-life care: managing common symptoms. Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(6):356-361.

56. Fudin, J. Opioid allergy, pseudo-allergy, or adverse effect? Pharmacy Times website. March 6, 2018. Accessed May 4, 2021. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/opioid-allergy-pseudo-allergy-or-adverse-effect

57. Abbas M, Moussa M, Akel H. Type I Hypersensitivity Reaction. Stat Pearls Publishing;2020. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560561/ .

58. Li PH, Ue KL, Wagner A, Rutkowski R, Rutkowski K. Opioid hypersensitivity: predictors of allergy and role of drug provocation testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1601-1606. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.035

59. Coleman JJ, Pontefract SK. Adverse drug reactions. Clin Med (Lond). 2016;16(5):481-485. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.16-5-481

60. Woodall HE, Chiu A, Weissman DE. Opioid allergic reactions. Palliative Care Network of Wisconsin website. July 2015. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.mypcnow.org/fast-fact/opioid-allergic-reactions/

61. Jain S, Kaplowitz N. 9.16- Clinical Considerations of Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity. In: Comprehensive Toxicology. 2nd ed. McQueen CA. Elsevier; 2010;369-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-046884-6.01014-9.

62. Soljoughian, M. Opioids: allergy vs. pseudoallergy. US Pharm. 2006;6:HS5-HS9. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/opioids-allergy-vs-pseudoallergy

63. Controlled substances drug diversion pharmacy technician toolkit. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists website. Accessed April 19,2021. https://www.ashp.org/Pharmacy-Technician/About-Pharmacy-Technicians/Advanced-Pharmacy-Technician-Roles-Toolkits/Controlled-Substances-Drug-Diversion-Pharmacy-Technician-Toolkit?loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly

64. Cagle JG, McPherson ML, Frey JJ, et al. Estimates of medication diversion in hospice. JAMA. 2020;323(6):566-568. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.20388

65. Cagle JG, Ware OD. Preventing medication diversion in home health & hospice. HomeCare Magazine. October 8, 2019. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://www.homecaremag.com/october-2019/preventing-medication-diversions

66. Parker, J. Strategies to prevent drug diversion in hospice care. Hospice News. April 29, 2019. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://hospicenews.com/2019/04/29/strategies-to-prevent-drug-diversion-in-hospice-care/

67. Risk evaluation and mitigation tool-kit: strategies to promote the safe use of opioids. Virginia Association for Hospices and Palliative Care website. 2012. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.virginiahospices.org/assets/docs/REM_TOOLKIT/REM%20Tool%20Kit%204Website_2019.pdf

68. What States Need to Know About PDMPs. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. July 1, 2020. Accessed May 7, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdmp/states.html#:~:text=A%20prescription%20drug%20monitoring%20program,a%20nimble%20and%20targeted%20response.

69. Cagle JG, Ware OD. 15 recommendations for preventing medication diversion & misuse in hospice care. Hospice Foundation of America website. August 2019. Accessed April 20, 2021. https://hospicefoundation.org/hfa/media/Files/Preventing-Medication-Diversion-in-Hospice-Recommendations-10-28-2019.pdf

70. Office of the Federal Register. Part 1306- Prescriptions. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations website. May 4, 2021. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=5ca5f28a5a2b14665924d3bef7178ebe&mc=true&node=se21.9.1306_111&rgn=div8