INTRODUCTION

Did the Mona Lisa have hypothyroidism? Discussions around the Mona Lisa’s enigmatic smile have fascinated art lovers for centuries but now some endocrinologists have started a new line of debate. They describe telltale signs, like swollen hands, thinning hair, and a lump in the neck, that point to the famous Mona Lisa exhibiting hypothyroidism. They even suggest that the disease contributed to her mysterious smile. Amusing! When you view the painting do you see the same signs?

Theodor Kocher, a Swiss physician who was award the Nobel Prize in 1909 for his work on the thyroid gland, described the first case of hypothyroidism in the mid-19th century.1 Effective treatment emerged about 100 years ago, so if the 16th century Mona Lisa had hypothyroidism, she might have suffered without knowing the cause. Patients with undiagnosed or inadequately treated hypothyroidism are at risk for cardiovascular problems, osteoporosis, and infertility.2

The thyroid gland’s main hormones are responsible for controlling the body’s energy production and metabolic rate and they affect nearly every organ system in the body. Having too little or too much of these hormones can have profound consequences on health.

Millions of Americans are affected by thyroid disease with most cases classified as hypothyroidism or underactive thyroid. Children, whose cognitive and physical development depends on normal thyroid function, can also be affected.3 Levothyroxine is used to treat hypothyroidism and is consistently among the most frequently prescribed medications in the United States (U.S.).4 Although less common, hyperthyroid disease is a serious endocrine disorder with profound health consequences if not properly treated.

THYROID GLAND AND FUNCTION

The thyroid gland is a small bow tie shaped endocrine gland that sits at the base of the neck. It produces two main hormones: tetraiodothyronine called thyroxine (T4), and triiodothyronine (T3). T4 and T3 control energy production and metabolic rate and influence nearly every organ system in the body including the brain, bowels, and skin. They regulate protein, carbohydrate, and fat metabolism by stimulating protein production and increasing oxygen needs at the cellular level. They are essential for proper fetal and neonatal development. Thyroid hormones influence body temperature, heart rate, appetite, mood, and digestion.2

Iodine is a constituent of T4 and T3 and sufficient dietary intake of iodine and its adequate uptake by the thyroid gland is necessary for proper thyroid function. The thyroid gland produces mostly inactive hormone in the form of thyroxine, called T4 because it has four iodine atoms. T4 is highly protein bound for transport to the liver where it undergoes deiodination (the removal of one iodine atom) resulting in T3. T3, like T4, is highly protein bound and must be released from its binding protein to be active. Equilibrium is maintained between bound and free T3; as the body demands more biologically active hormone more T3 is released from the binding protein. Free T3 is the main biologically active form of thyroid hormone.2

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Thyroid Axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis governs thyroid hormone production by regulating the synthesis and secretion of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), also called thyrotropin. The hypothalamus is the part of the brain responsible for monitoring thyroid hormone levels in the body. When the hypothalamus detects low levels of thyroid hormone in the body, it releases a hormone called thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH). TRH stimulates the pituitary gland, the small pea-size gland sitting at the base of the brain, to secrete TSH. TSH, in turn, instructs the thyroid gland to produce more T4 and T3. High levels of T4 in the body inhibit TSH secretion while low levels of T4 stimulate TSH secretion. Disease affecting any part of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis can result in thyroid hormone imbalances and disease.2

THYROID DISEASE AND ETIOLOGY

Thyroid disease is an endocrine disorder. Primary thyroid disease refers to disease of the thyroid gland. Secondary thyroid disease is far less common and refers to disease affecting the hypothalamus or pituitary gland resulting in thyroid dysfunction. Thyroid disease is classified as either hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism.

Hypothyroid Disease

Hypothyroid disease occurs when inadequate thyroid hormone is available to the body. It is often referred to as an underactive thyroid and it is the most common form of thyroid disease. Hypothyroid disorders are categorized as either primary hypothyroidism or secondary hypothyroidism. The vast majority of cases are primary hypothyroidism.2

Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) is the most common cause of primary hypothyroidism in the U.S. Japanese physician Hakaru Hashimoto first described the disease in 1912. It wasn’t until decades later that it was recognized as an autoimmune disorder and it is now considered the most prevalent autoimmune disease.5 Many patients do not realize that their hypothyroid condition is caused by this autoimmune disorder.

HT is characterized by infiltration and destruction of thyroid cells by leukocytes (white blood cells). A chronic autoimmune inflammation ensues resulting in atrophy and fibrosis of the thyroid gland that leads to hypothyroidism. Circulating thyroid autoantibodies, anti-thyroperoxidase antibody (anti-TPO Ab), and anti-thyroglobulin antibody (anti-Tg Ab) can be detected but clinicians usually don’t measure them since all treatment of hypothyroidism is similar.6

Women are more likely to develop HT and often have a family history, implicating a genetic component. The presence of other autoimmune disorders is common and prevalence is higher among those with chromosomal disorders like Down syndrome.2

Patients may present with thyroiditis (inflammation of the thyroid gland) and symptoms of hypothyroidism, like weight gain and fatigue, but not always. Symptoms can develop gradually and go unnoticed. Laboratory assessment of thyroid function (discussed below) confirms the diagnosis. Individuals diagnosed with HT require lifelong treatment with the thyroid replacement hormone levothyroxine.6

HT’s complications can manifest particularly in untreated or undertreated individuals including2:

- Lipid disorders (elevated total cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides)

- Anemia

- Menstrual abnormalities

- Infertility

- Hyponatremia

- Thyroid associated orbitopathy

- Increased risk for papillary thyroid carcinoma

Lipid disorders are of particular concern because they can contribute to coronary artery disease. Anemia is observed in 30% to 40% of patients. Recent research has suggested greater risk for recurrent pregnancy loss in patients with HT and an additional autoimmune disorder, but more research is needed to fully understand the link.7

Most complications of HT are rare but prescribers must monitor and treat complications as they arise to optimize patient management.8

Researchers have also noted vitamin D deficiency in HT. A randomized, double blind, clinical trial observed that supplementation with vitamin D reduced circulating thyroid autoantibodies.5 The researchers suggest a possible role for vitamin D in the alleviation of disease activity but acknowledge the need for further studies before introducing this intervention to clinical practice. Despite the need for additional research, treating vitamin D deficiency in patients with HT may be warranted.

Gut microbiota are considered intrinsic regulators of thyroid autoimmunity. Scientists have studied the composition of the microbiota in patients with thyroid autoimmunity and have found it to be altered in HT.9 Clinical implications of this research are not fully understood, but further research may determine the role these findings may have in HT management.

With early diagnosis, prompt treatment, proper follow-up care, and attention to associated complications, HT’s prognosis is excellent, and patients lead a normal life.10

Iodine Deficiency Hypothyroidism

Although uncommon in America, iodine deficiency is the leading cause of hypothyroidism worldwide. Adequate iodine intake is necessary for the thyroid gland to function properly, and it is critical for normal fetal and neonatal development. The recommended daily allowance (RDA) for adults is 150 mcg and it increases to 250 mcg in pregnancy and to 290 mcg during lactation. Goiter (an abnormal enlargement of the thyroid gland) is common as the thyroid gland enlarges in an attempt to sequester iodine to make thyroid hormone.11,63

Universal salt iodization programs have dramatically reduced iodine deficiency-related thyroid disease.12 Historically, iodine deficient areas in the U.S. included the mountainous regions and the so called “goiter belt” around the Great Lakes. Most Americans now consume adequate amounts of iodine in their diets by using iodized salt and by eating dairy products, eggs, and seafood. However, certain populations may still be at risk, including vegans, pregnant women, and people who don’t use iodized salt.11 Most alternative milk products are low in iodine and processed foods like canned soup and specialty salts–including kosher, Himalayan, and sea salt–rarely provide iodine.13 Healthcare practitioners must be aware of iodine deficiency’s consequences, especially during pregnancy.11,63

Thyroid diets have gained interest among patients and circulate widely on the Internet. These diets promote avoiding particular foods to achieve optimal thyroid function. Certain foods including broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, and soy contain goitrogens, which are substances that interfere with iodine uptake by the thyroid. For most people in the U.S. who consume adequate amounts of iodine, eating foods containing goitrogens is not a concern. People with iodine deficiency who eat an abundance of these foods may have trouble consuming enough iodine.13,63

Thyroidectomy and Cancer Treatment Resulting in Hypothyroidism

Thyroidectomy, the surgical removal of the thyroid gland, is sometimes indicated in cancer treatment and in some cases of hyperthyroidism. Thyroidectomy results in hypothyroidism and patients require life-long thyroid hormone replacement with levothyroxine.14

Most thyroid cancers respond well to treatment, but a small percentage can be very aggressive. Treatment of thyroid cancer often results in hypothyroidism and patients require lifelong treatment with thyroid replacement hormone.14

Medication-Induced Hypothyroidism

The pharmacy team must be aware that certain medications can affect thyroid function. Table 1 lists common medications that can cause hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. The medications that cause hypothyroidism decrease synthesis of T4/T3, inhibit T4/T3 secretion, and/or cause thyroiditis.15

| Table 1. Medications that May Lead to Thyroid Dysfunction

|

| Drug class/medications |

Hypothyroidism |

Hyperthyroidism |

| Antidysrhythmic:

|

| Amiodarone |

X |

X |

| Bipolar Disorder Medication:

|

| Lithium |

X |

X |

| Thyroid Medications:

|

| PTU |

X |

|

| Methimazole |

X |

|

| Radioactive Iodine |

X |

|

| Cancer Medications:

|

| Biological response modifiers: |

| Interferon |

X |

|

| Interleukin-2 |

X |

|

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: |

| Sunitinib |

X |

|

| Sorafenib |

X |

|

| Checkpoint inhibitors: |

|

|

| Nivolumab |

X |

X |

| Pembrolizumab |

X |

X |

| Ipilimumab |

X |

X |

| Multiple Sclerosis Medication:

|

| Alemtuzumab |

|

X |

Medications that cause thyroid disorders are important treatments and, in most cases, they cannot be discontinued; any drug-induced hypothyroidism requires levothyroxine.

Amiodarone structurally resembles thyroid hormone and is often implicated in thyroid dysfunction, mostly hypothyroidism.16 It is comprised of 37% iodine, so a 200 mg dose provides 75 mg of organic iodide, which is 100 times more than required. Researchers estimate thyroid abnormalities occur in 14% to 18% of patients taking long-term amiodarone but a meta-analysis found that with low doses, the incidence is lower (3.7%).17 Lithium can inhibit thyroid hormone release resulting in hypothyroidism; it usually occurs in younger women within the first two years of therapy. Antineoplastic agents may cause thyroid dysfunction in 20% to 50% of patients.18 Pharmacists must educate patients about the need for routine thyroid function assessment when receiving these medications.

Hyperthyroid Disease

Hyperthyroidism is characterized by excessive metabolism and secretion of thyroid hormones. It is less common than hypothyroid disease. Graves’ disease, thyroiditis, multi-nodular goiter, and toxic nodular goiter (benign growths on the thyroid gland that produce thyroid hormone in excess) can also cause hyperthyroid disease. Ingestion of too much external thyroid hormone is another possible cause of hyperthyroidism.19

Graves’ Disease

Graves’ disease (GD) accounts for most cases of hyperthyroidism. GD is an autoimmune disorder caused by a stimulatory autoantibody against the thyroid receptor for TSH. Most autoantibodies are inhibitory; in GD, the autoantibody is stimulatory. Overstimulation of the thyroid gland results in the overproduction of T4 and T3 leading to hyperthyroidism.12

Graves’ disease, like HT, appears to have a genetic link and is often comorbid with other autoimmune disorders. Risk factors for GD include smoking and iodine deficiency. In the case of iodine deficiency, multifocal autonomous growth of the thyroid gland can occur and result in thyrotoxicosis (excess levels of thyroid hormone in the body).20 Women are affected at a higher rate and children can also be affected. GD’s clinical presentation may be dramatic or subtle and goiter may or may not be present. Laboratory assessment of thyroid function is used to help diagnose GD.

Researchers have studied the composition of gut microbiota in patients with GD and similar to findings in HT, have found it to be altered. The researchers suggest the findings from this randomized controlled trial may offer an alternative noninvasive diagnostic methodology for GD.21 Further research is needed to elucidate the role microbiota may play in thyroid autoimmunity.

Thyroid Eye Disease

Thyroid eye disease is a progressive, potentially sight threatening ocular disease that is reported in almost half of patients who have GD. It arises from a separate autoimmune process involving autoantibodies that activate an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) mediated signaling complex on cells within the eye orbit. The most common clinical feature is proptosis (bulging eyes) with edema and erythema of the surrounding eye tissue, but patients may also experience a skin manifestation called thyroid dermopathy (a nodular diffuse thickening of the skin on the legs). Patients with thyroid eye disease often complain of dry and gritty ocular sensation, photophobia, excessive tearing, double vision, and pressure sensation behind the eyes. Severe disease occurs in 3% to 5% of patients causing intense eye pain and inflammation, and threatening sight.22

Recently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the monoclonal antibody teprotumumab for treatment of adults with thyroid eye disease, marking a significant advancement in treatment. Prior to this approval, treatment options only included steroids or surgery.23

Medication Induced Hyperthyroidism

Like medication that can cause hypothyroidism, some medication can cause hyperthyroidism. The pharmacy team must be knowledgeable of the medications that can cause hyperthyroidism that warrant close monitoring of thyroid function (See Table 1). Patients should understand the importance of routine thyroid function assessment when taking medications that can affect thyroid function.

Amiodarone-associated hyperthyroidism is less common than amiodarone-associated hypothyroidism; still, it is estimated to occur in 3% of patients. Onset of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis (elevated levels of free thyroid hormone) can be sudden and require rapid assessment and treatment.16 Pharmacists must educate their patients about the symptoms of hyperthyroidism and instruct them to report them immediately if encountered.

PAUSE AND PONDER: How many of your patients take medications that might cause thyroid dysfunction? Why is it important to tell these patients that some of their medications might influence the thyroid gland?

PREVALENCE

As many as 20 million Americans are affected by thyroid disease. Clinicians diagnose hypothyroidism in nearly five of 100 Americans aged 12 years and older.24 Thyroid disease affects men, women, and children. Women are disproportionately affected at a 10 to 15 times higher rate, and it’s estimated one in eight women will develop some form of thyroid disease in their lifetime.24

HT is most often diagnosed between the ages of 40 to 60 years. Prevalence increases with age.8 Twenty percent of adults older than 75, most of them women, have insufficient levels of thyroid hormone.24 The Colorado Thyroid Disease Prevalence Study, a cross-sectional study conducted more than 20 years ago, reported the prevalence of hypothyroid disease in symptomatic and asymptomatic adults at 9.5%.25 In people not taking thyroid hormone, prevalence was 8.5% and 0.4% for subclinical and overt disease, respectively.10

Hyperthyroidism is much less common than hypothyroidism. Prevalence of hyperthyroidism in the U.S. is estimated at 1.3%. GD is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism followed by toxic nodular goiter. GD is estimated to affect 1% of the population, mainly women of childbearing age. Incidence increases with age, and it is observed more frequently in Caucasians compared to other races. Mild hyperthyroidism occurs at a higher rate in iodine deficient geographic areas.12

SYMPTOMS

Because thyroid hormones affect nearly every organ system in the body thyroid disease’s symptoms are wide ranging and numerous. Symptoms vary depending on the type of thyroid disease and patients may experience few or many symptoms.26 Clinicians should routinely monitor patients for symptoms of thyroid disease, especially those at risk for thyroid disease including elderly women (See Table 2).27

| Table 2. Thyroid Disease’s Common Symptoms |

|

Hypothyroidism |

Hyperthyroidism |

| Whole body |

Fatigue, lethargy, cold sensitivity |

Hunger, fatigue, weakness, sweating, increased appetite, heat intolerance, insomnia |

| Mood/behavioral |

Depression, irritability, sluggish, brain fog |

Nervousness, restlessness, hyperactivity, panic attacks |

| Cardiac |

Bradycardia, elevated cholesterol |

Tachycardia, palpitations |

| Weight |

Weight gain |

Weight loss |

| Hair, skin, nails |

Hair loss, dry skin/hair, brittle nails |

Hair loss, warm skin |

| Eyes/face |

Periorbital edema, puffy face |

Proptosis (abnormal protrusion of eyes) |

| Gastrointestinal |

Constipation |

Frequent bowel movements |

| Menstruation/fertility |

Heavy or irregular menstrual periods, fertility problems |

Amenorrhea, lighter or irregular menstrual periods, fertility problems |

| Musculoskeletal |

Joint/muscle pain |

Osteoporosis |

| Thyroid presentation |

May be enlarged |

May be enlarged |

Weight gain is a common and often first symptom of hypothyroidism. Up to 82% of women with HT have excess body weight and a third suffer from obesity.28 Despite achieving euthyroidism (normal thyroid function) with levothyroxine treatment, many women continue to struggle to lose weight. Caloric reducing diets are often unsuccessful and excess body weight increases risk for comorbidities.29

Food sensitivity and the effects of elimination diets on autoimmune disease have gained interest. An interventional/observational study evaluated the effect of an elimination diet in obese women diagnosed with HT. The researchers observed that women eliminating sensitive foods (foods that may cause an IgG antibody reaction) in addition to caloric reduction had a greater decrease in body mass index (BMI) when compared to women only reducing caloric intake.30 Improvement in thyroid function laboratory parameters was also observed in the group eliminating sensitive foods.31

LABS TO ASSESS THYROID FUNCTION

Thyroid function is assessed mainly through readily available laboratory blood tests. Results of basic thyroid function laboratory tests largely differentiate and diagnose thyroid disease (See Table 3).

Table 3. Thyroid Function Tests in Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism32

|

TSH (Thyrotropin) |

FT4 (Thyroxine) |

T3 |

| Lab reference range* |

0.5-4.8 mIU/L |

0.7-1.8 ng/dL |

80-220 ng/dL |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Primary, untreated |

High |

Low |

Low or normal |

| Secondary to pituitary disease |

Low or Normal |

Low |

Low or normal |

| Hyperthyroidism |

| Untreated |

Low |

High |

High |

| T3 toxicosis |

Low |

Normal |

High |

*Reference ranges may vary among laboratories.

TSH is the best measurement to assess thyroid function. A normal TSH essentially rules out thyroid disease, except in the less common cases of disease affecting the hypothalamus or pituitary gland. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) recommends routine screening of TSH in adults beginning at age 35 and repeating the test every five years.27

T4 is the primary thyroid hormone circulating in the blood. T4 is found in the body in two forms: free T4 and bound T4. More than 99% of T4 is bound. Because T4 is converted into T3, free T4 (FT4) is the more important hormone to measure. Any changes show up in T4 first; therefore, FT4 reflects thyroid gland function more accurately.33 Assessment of T3 is primarily used to diagnose and manage hyperthyroidism. It is rarely assessed in hypothyroidism since it’s the last test to become abnormal.34

Patients with thyroid autoimmunity disease develop thyroid autoantibodies. Measurement of autoantibodies may help diagnosis, but clinicians need not monitor them routinely for disease management. Physicians typically order TSH with reflex to FT4 to assess thyroid function in disease management. Reflex testing allows the laboratory to automatically add the FT4 test to the blood sample based on an abnormal TSH result.35

Clinicians sometime use radioactive iodine uptake (a non-blood test) to assess thyroid function. Because iodine is a necessary component of thyroid hormone, administering radioactive iodine and calculating its uptake by the thyroid can determine if the gland is functioning properly. Very high uptake is associated with hyperthyroidism while low iodine uptake indicates hypothyroidism.34

TREATMENT APPROACHES

Levothyroxine

Levothyroxine sodium tablets (Synthroid and many generics) are synthetic T4 and indicated as replacement therapy in all hypothyroidism, regardless of the cause. Thyroid replacement hormone has a narrow therapeutic index and prescribers must individualize each patient’s levothyroxine dose. It is available in 12 different strengths, making it possible for prescribers to titrate doses carefully and avoid under- or over-treatment. Tablets are color-coded and are available from many manufacturers. (See Table 4.)

Table 4. Various Strengths and Colors of Levothyroxine Tablets

| Strength |

Color |

| 25 mcg |

Orange |

| 50 mcg |

White |

| 75 mcg |

Violet |

| 88 mcg |

Mint green |

| 100 mcg |

Yellow |

| 112 mcg |

Rose |

| 125 mcg |

Brown |

| 137 mcg |

Deep blue |

| 150 mcg |

Light blue |

| 175 mcg |

Lilac |

| 200 mcg |

Pink |

| 300 mcg |

Green |

Variability in levothyroxine absorption may exist across manufacturers. A cohort study in the Netherlands evaluated a forced switch of levothyroxine brand. The researchers concluded that a dose-equivalent levothyroxine brand switch might necessitate a dose adjustment.36 The ATA recommends using a consistent manufacturer. If a brand switch is made, the pharmacy team must inform prescribers; it may necessitate a dose adjustment.37

Sidebar: Tech Tasks for Thyroid Medications

- Inform patients about the importance of using a consistent brand of levothyroxine.

- Note brand of levothyroxine on each patient’s profile.

- Review levothyroxine shipments when restocking to assure consistent brand use.

- Tag all bags and inform the patient if a brand switch is made.

Peak therapeutic effect of levothyroxine is seen in four to six weeks. Prescribers often start levothyroxine at low doses and titrate in small increments of 12.5 to 25 mcg every four to six weeks based on TSH testing until achieving euthyroidism.38 Average full replacement dose is 1.6 mcg/kg/day. Current ATA guidelines recommend adjusting the levothyroxine dose to resolve symptoms of hypothyroidism and to keep the TSH level within the range of 0.4 to 4 mIU/L.29 Clinicians should assess thyroid function in patients on stable doses of levothyroxine every six to 12 months and within six to eight weeks of any dose change. Ongoing assessment helps avoid under- or over-replacement.38

Adverse reactions associated with levothyroxine therapy are primarily those of hyperthyroidism and include the following37:

- Anxiety

- Diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Hair loss

- Heat intolerance, excessive sweating

- Increased appetite

- Increased heart rate

- Muscle weakness

- Nervousness

- Palpitations

- Weight loss

Over-replacement with levothyroxine can lead to serious consequences and can put elderly patients at risk for cardiac arrhythmias, especially atrial fibrillation.10 Complications of over-replacement include

- Accelerated bone loss

- Increased cardiac contractility

- Increased cardiac wall thickness

- Increased heart rate

- Osteoporosis

- Reduction in bone mineral density

Medications, supplements, food, coffee, and even orange juice can decrease levothyroxine’s absorption.10 Levothyroxine is taken with water one hour before breakfast and any other prescription medications. Calcium, iron, antacids, cholestyramine, and sucralfate can inhibit its absorption and must be separated by at least four hours.37 Individuals with celiac disease or gastric bypass surgery may absorb medication inadequately.40,41

Bedtime dosing of levothyroxine offers an alternative to morning dosing. Randomized controlled trials have found patients taking the medication in the evening had improved thyroid hormone status control.38,42 Patients struggling with morning dosing may find evening dosing easier. The ATA recommends that if levothyroxine is taken at bedtime that it be separated by three hours from the evening meal.43

Because levothyroxine is usually administered for life, dose adjustment is often necessary to optimize therapy throughout a patient’s lifetime.44 Situations that necessitate possible dose adjustment of levothyroxine include

- Aging (age older than 65)

- Diagnosis of new medical conditions

- Pregnancy

- Start of new medications

- Weight changes

The Colorado Thyroid Disease Prevalence study assessed thyroid function, symptoms, and corresponding lipid levels in more than 25,000 participants. Among patients taking thyroid medication, only 60% were within the normal range of TSH. Modest TSH elevations corresponded to changes in lipid levels that may affect cardiovascular health.25 Optimization of levothyroxine therapy requires that the healthcare team recognize the need for dose adjustments throughout a patient’s life.

PAUSE AND PONDER: Among your patients being treated for hypothyroidism, how many also take calcium supplements? How many of these patients know to separate them from levothyroxine by four hours?

Liothyronine

Liothyronine (Cytomel) is synthetic T3. It is not recommended, either alone or in combination with levothyroxine, as first line treatment for hypothyroidism. Combination therapy hopes to mimic thyroid hormone physiology more closely; however, current guidelines do not suggest routine use of this approach.10 A 2016 randomized, double blind, crossover study evaluated combination therapy in 32 patients and found no clear clinical benefit and observed increased heart rate in patients receiving it.45A trial, however, may be indicated in a small group of patients who remain symptomatic despite adequate levothyroxine monotherapy.46

Iodine

Patients with iodine deficient hypothyroidism are treated with iodine supplements to correct the deficiency while levothyroxine is used to achieve euthyroidism. When the iodine level has been restored and goiter size has decreased, levothyroxine may be interrupted. Prescribers should reassess thyroid function in four to six weeks.11

Consumption of too much iodine can have a negative impact on thyroid health. The safe upper limit of iodine for adults is 1.1 mg/day.63 Iodine toxicity may lead to thyroiditis, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and thyroid papillary cancer.47 Pharmacists should be aware that drug interactions with potassium iodine exist. It can interact with antithyroid drugs and when potassium iodide is taken with ACE inhibitors or potassium sparing diuretics, serum potassium can increase.13

Selenium

Selenium is an important micronutrient in the diet and increases active thyroid hormone production. The RDA for selenium is 55 mcg/day. Selenium supplements are used to treat or prevent selenium deficiency. Doses exceeding 400 mcg/day can be toxic. Signs of toxicity include brittle hair and nails, diarrhea, irritability, and nausea. Extremely high intakes of selenium can cause severe problems, including difficulty breathing, tremors, kidney failure, heart attacks, and heart failure. Most people consume adequate selenium through the diet, which is preferred. Consuming two Brazil nuts daily can provide adequate selenium intake; each nut contains 68 to 91 mcg of selenium, so people should not consume too many. Selenium is also found in oysters, tuna, whole-wheat bread, sunflower seeds, meat, mushrooms, and rye.48

Subclinical Hypothyroid Disease

Subclinical hypothyroidism is a common condition occurring in about 15% of older women and 10% of older men.2 It is a persistent condition in which TSH levels are elevated but free T4 levels remain normal. Treating subclinical hypothyroidism with levothyroxine results in an improved quality of life for many while others show no benefit and continue to complain of symptoms despite treatment.

The decision to treat subclinical hypothyroidism is being reevaluated after a large European study found no clear benefit with treatment.3 Published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2017, this double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial concluded levothyroxine provided no apparent benefits in older people with subclinical hypothyroidism.49 Investigators are conducting more research to evaluate the effect of discontinuing levothyroxine in subclinical hypothyroidism.50 They hope to determine if discontinuing levothyroxine in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism is safe or will reduce quality of life.

For now, prescribers should follow current clinical practice guidelines, which state that they should tailor the decision to treat subclinical hypothyroidism to the individual patient when the serum TSH is less than 10 mIU/L. Prescribers should consider the presence of symptoms and how likely the patient will progress to overt hypothyroidism when making the decision to treat.24

Antithyroid Drugs

The treatment goal for hyperthyroid disease is to lower excessive thyroid hormone levels and achieve euthyroidism. The two antithyroid drugs (ATD) available in the U.S. for the treatment of hyperthyroidism are methimazole (Tapazole) and propylthiouracil (PTU). Hepatotoxicity has been reported with both medications but methimazole has been associated with far fewer cases. Therefore, methimazole is used as first line therapy, except in pregnancy.51

ATDs inhibit T4 and T3 synthesis by blocking oxidation of iodine in the thyroid gland. PTU also partially blocks peripheral conversion of T4 to T3. Beta-blockers can provide symptomatic relief in patients with hyperthyroidism.

Methimazole is available in 5 mg and 10 mg tablets. The starting dose is 5 mg to 20 mg orally every eight hours. Prescribers must titrate the dose over time to the lowest dose needed to maintain euthyroidism. Maintenance doses range from 5 mg to 30 mg/day administered once daily. Once euthyroidism is achieved, patients usually continue the ATD for another 12 to 18 months. The prescriber should check thyroid function four to six weeks after therapy initiation and then every two to three months once the patient is euthyroid.12

PTU’s labeling carries a boxed warning for acute liver failure, and it is reserved for use in those who cannot tolerate other treatments such as methimazole, radioactive iodine, or surgery.52 It is also recommended for use in the first trimester of pregnancy because birth defects have been associated with methimazole. PTU is available as a 50 mg tablet. The initial starting dose is 50 mg to 150 mg orally every eight hours and the maintenance dose is usually 50 mg every 8 to 12 hours.53

Minor side effects occur in about 5% of patients receiving an ATD. Side effects include53

- Agranulocytosis (severe drop in white blood cells)

- Arthralgia

- Gastrointestinal distress

- Hepatotoxicity

- Pruritus

- Vasculitis (dangerous inflammation of blood vessels)

Serious side effects are less common at lower doses; patients should be maintained at the lowest possible dose needed to achieve euthyroidism. Although rare, hepatotoxicity and agranulocytosis can be life threatening. Pharmacists should educate patients to report signs of agranulocytosis, such as sudden fever, sore throat, or chills, to their prescribers immediately. Prescribers should obtain a baseline serum liver profile and white blood cell count before starting an ATD. Most side effects occur within the first 90 days of therapy. Vasculitis is more common with longer duration of therapy.

A drawback of ATD therapy is the high relapse rate. A longitudinal cohort study concluded that patients initially treated with an ATD had about a 50% relapse rate and 25% felt they had not fully recovered in six to 10 years.54

Recent studies have shown that longer treatment time with an ATD can achieve higher remission rates. A randomized, parallel-group study compared relapse rates in patients receiving longer-term versus conventional-length methimazole therapy in GD. The authors concluded that low-dose methimazole treatment for 60 to 120 months was safe and effective and had a higher remission rate compared to conventional treatment for 18 to 24 months.55

Long-term methimazole therapy was also evaluated in juvenile GD in a randomized parallel trial. Patients receiving short-term methimazole therapy were almost three times more likely to relapse than those on long-term therapy. The researchers found long-term methimazole treatment of 96 to 120 months to be safe and effective with a significantly higher four-year cure rate.56

Teprotumumab

The FDA’s approval of teprotumumab (TEPEZZA) in January 2020 was the most significant advance in treating thyroid eye disease in decades. Teprotumumab binds to IGF-1R and blocks its activation and signaling. It was shown to improve the course of thyroid eye disease in patients in two separate clinical trials, leading to this monoclonal antibody’s approval.23,57 Proptosis and diplopia improved, as did eye pain, redness and swelling, and quality of life. Serious adverse events were uncommon. The most common adverse reactions observed were

- alopecia

- altered sense of taste

- diarrhea

- dry skin

- fatigue

- headache

- hearing loss

- hyperglycemia

- muscle spasm

- nausea

The FDA approved teprotumumab to be given as an infusion every three weeks for a total of eight doses. Patients completing the course of therapy showed significant improvement in symptoms associated with thyroid eye disease. Infusion reactions are reported in about 4% of patients. Dose is based on weight. The first dose is 10 mg/kg, and then the dose is increased to 20 mg/kg for the remaining seven infusions. Teprotumumab is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women of childbearing age must be counseled on pregnancy prevention during treatment and for six months following the last dose.58

PAUSE AND PONDER: Which patients with thyroid disease in your practice might benefit from teprotumumab? What is important to tell them about this new biologic?

Surgery

Thyroidectomy is not used as a first line approach for treating hyperthyroidism. It is reserved for patients who refuse radioactive iodine after relapsing on an ATD, patients who cannot tolerate an ATD, or patients with very large goiter, multinodular goiter, or toxic adenoma. Thyroidectomy destroys the thyroid gland and if indicated, patients require lifelong levothyroxine therapy.

Radioactive Iodine

In the U.S., radioactive iodine is the most common treatment for hyperthyroidism. Radioiodine therapy, like surgery, destroys the thyroid gland requiring patients to be on lifelong levothyroxine therapy.

In the last 20 years, radioiodine has been used less frequently.19 Many patients report a lower quality of life after receiving radioactive iodine than patients receiving ATD or surgical treatment.59 A randomized parallel group trial found that long-term methimazole, when compared to radioiodine, was safe, effective, and not inferior to radioiodine further supporting the use of ATD over radioiodine.60

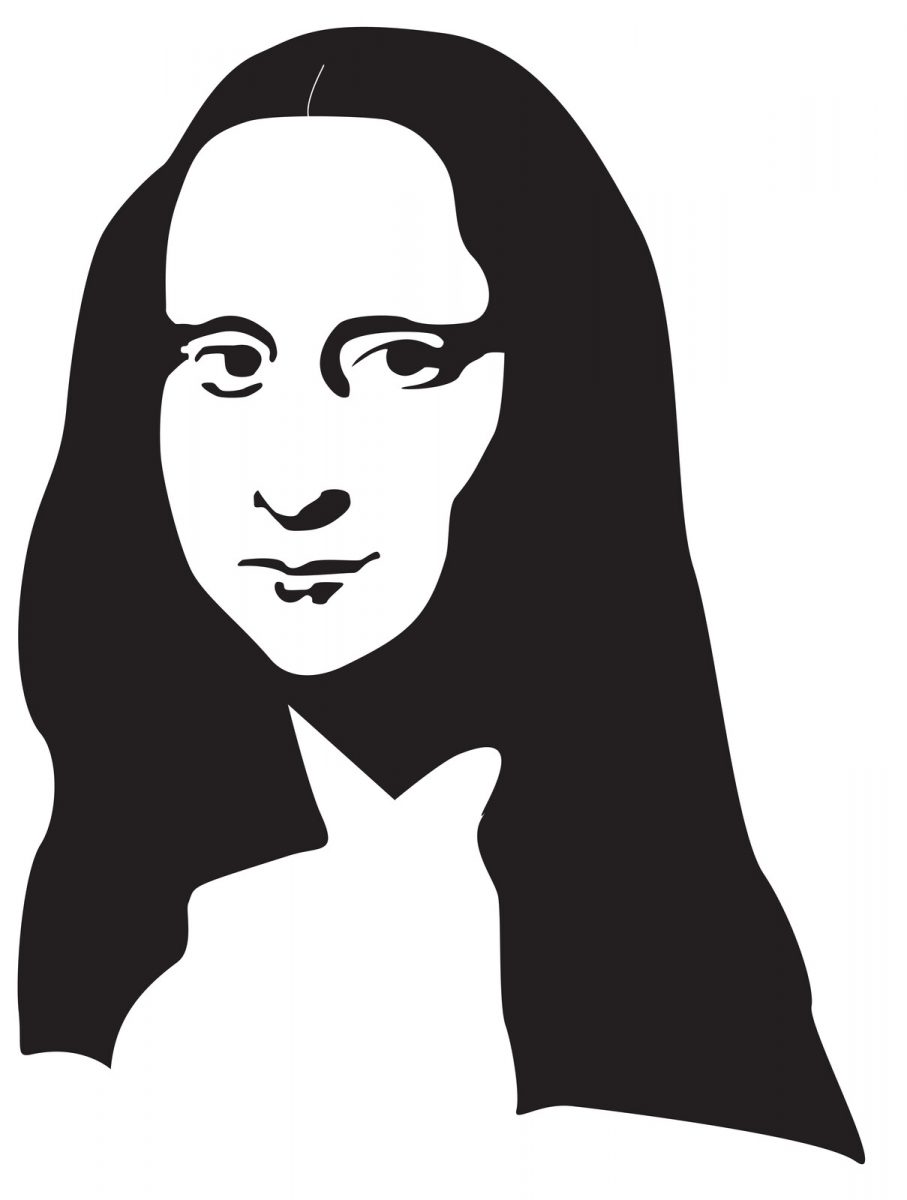

Pregnancy

Undiagnosed or inadequately treated hypothyroidism during pregnancy can lead to miscarriage, preterm delivery, or developmental disorders in children. Levothyroxine is safe in pregnancy, but pregnant patients may require a 30% increase in levothyroxine dose to maintain euthyroidism. During pregnancy, attending healthcare providers should titrate levothyroxine doses against TSH, which has trimester-specific ranges. Postpartum TSH levels are similar to preconception levels, so the dose of levothyroxine should return to the preconception dose following delivery.61

Iodine is a critical mineral for proper fetal development and iodine needs increase by at least 50% in pregnancy and lactation. Pregnant women should receive a prenatal vitamin containing 150 mcg of iodine during pregnancy and lactation. Unfortunately, prenatal vitamins contain variable and inconsistent amounts of iodine. Close to 40% of marketed prenatal vitamins in the U.S. contain no iodine and when measured, the actual iodine content varied between 33 and 610 mcg.11 Healthcare practitioners must be vigilant in assuring that iodine requirements are met during pregnancy and lactation when iodine requirements increase. The ATA recommends that women receive 150 mcg of supplemental iodine daily during pregnancy and lactation and that all prenatal vitamin/mineral preparations contain 150 mcg of iodine.11

Hyperthyroidism in pregnancy requires special consideration. Care givers must stabilize women undergoing treatment for GD who intend to become pregnant prior to conception. Prescribers should advise women to delay attempts at conception until they achieve a stable euthyroid state, whenever possible.62 Additionally they should treat hyperthyroidism during pregnancy with the lowest possible dose of PTU because methimazole has been associated with cases of congenital malformation.

The majority of patients with thyroid eye disease are women of childbearing age. Physicians must explain treatment limitations to patients who are contemplating pregnancy. Teprotumumab is contraindicated in pregnancy. Caregivers must provide contraceptive counseling to women of childbearing age with thyroid eye disease treated with teprotumumab during treatment and for the six months following therapy.23

Pharmacy Team’s Role

The pharmacy team can have a positive impact on the successful management of patients with thyroid disease by educating and screening patients regarding

- Adverse effects associated with their thyroid medications

- Importance of medication adherence

- Laboratory assessment of thyroid function

- Screening for drug interactions

- Signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism

CONCLUSION

Thyroid disease affects millions in the U.S. and most cases are well controlled with pharmacological management. Adherence to thyroid disease medications is important. A knowledgeable pharmacy team can promote good practices and provide patient education, having a positive impact on patient care. Proper management allows most patients to have an excellent prognosis and quality of life.

With your newly gained knowledge, take another look at the Mona Lisa. Did Leonardo da Vinci, a man before his time, notice a thyroid disorder that he captured in his famous painting and did it intentionally contribute to her enigmatic smile?