Learning Objectives

After completing this knowledge-based continuing education activity, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians will be able to

|

|

Release Date: December 5, 2025

Expiration Date: December 5, 2028

Course Fee

FREE

There is no grant funding for this CE activity

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-25-073-H06-P

Pharmacy Technician: 0009-0000-25-073-H06-T

Session Codes

Pharmacist: 22YC66-BXV44

Pharmacy Technician: 22YC66-VBT84

Accreditation Hours

0.5 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-25-073-H06-P/T will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Kelsey Giara, PharmD

Freelance Medical Writer

Pelham, NH

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Dr. Giara does not have any relationships with ineligible companies and therefore has nothing to disclose.

ABSTRACT

Researchers have studied intradermal vaccination for various diseases for over a decade, so it was only a matter of time before pharmacists would be asked to learn this route of administration. This is arguably the most challenging method of vaccine administration, and inaccurate technique could render an immunization ineffective. Given the need for intradermal administration of the monkeypox vaccine, pharmacists should be prepared to offer intradermal vaccination to eligible individuals to increase immunization rates, slow viral spread, and improve outcomes for affected individuals.

CONTENT

Content

INTRODUCTION

Major developments to vaccines and vaccine administration in recent years have demanded a great deal from pharmacists. The coronavirus disease-19 pandemic asked us to fight misinformation and vaccine hesitancy to educate the public about a new virus and new vaccine technology. We’ve been challenged to keep up with booster recommendations and the increased workflow that comes with vaccine administration. Many of us also taught our pharmacy technicians how to immunize.

Now, with the emergence of monkeypox comes yet another new vaccine with an unfamiliar method of administration (see our FREE monkeypox activity for a more in-depth discussion about this virus). In August 2022, the United States (U.S.) declared monkeypox a public health emergency and ramped up efforts to vaccinate at-risk individuals subcutaneously (a method with which pharmacists are generally familiar).1 Shortly thereafter, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognized that the country’s supply of monkeypox vaccine was unable to meet the current demand given the rapid spread of the virus.2 Administering the vaccine intradermally only requires one-fifth of the subcutaneous dose, so the FDA issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) allowing healthcare providers to use this method of administration. This effectively increased the total number of available doses by up to five-fold.2

In September 2022, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services authorized pharmacists, pharmacy interns, and pharmacy technicians, as appropriate, to administer monkeypox vaccines and therapeutics, under certain conditions.3 Pharmacists should be prepared to offer intradermal vaccination to eligible individuals to increase vaccination rates, slow viral spread, and improve outcomes both for this virus and any future viruses for which this applies.

THE ROLE OF INTRADERMAL ADMINISTRATION

Researchers have studied intradermal vaccination for a range of viral diseases, but only a few things are administered intradermally including4,5

- tuberculosis skin testing

- BCG (tuberculosis) vaccine

- rabies vaccine

- allergy skin testing

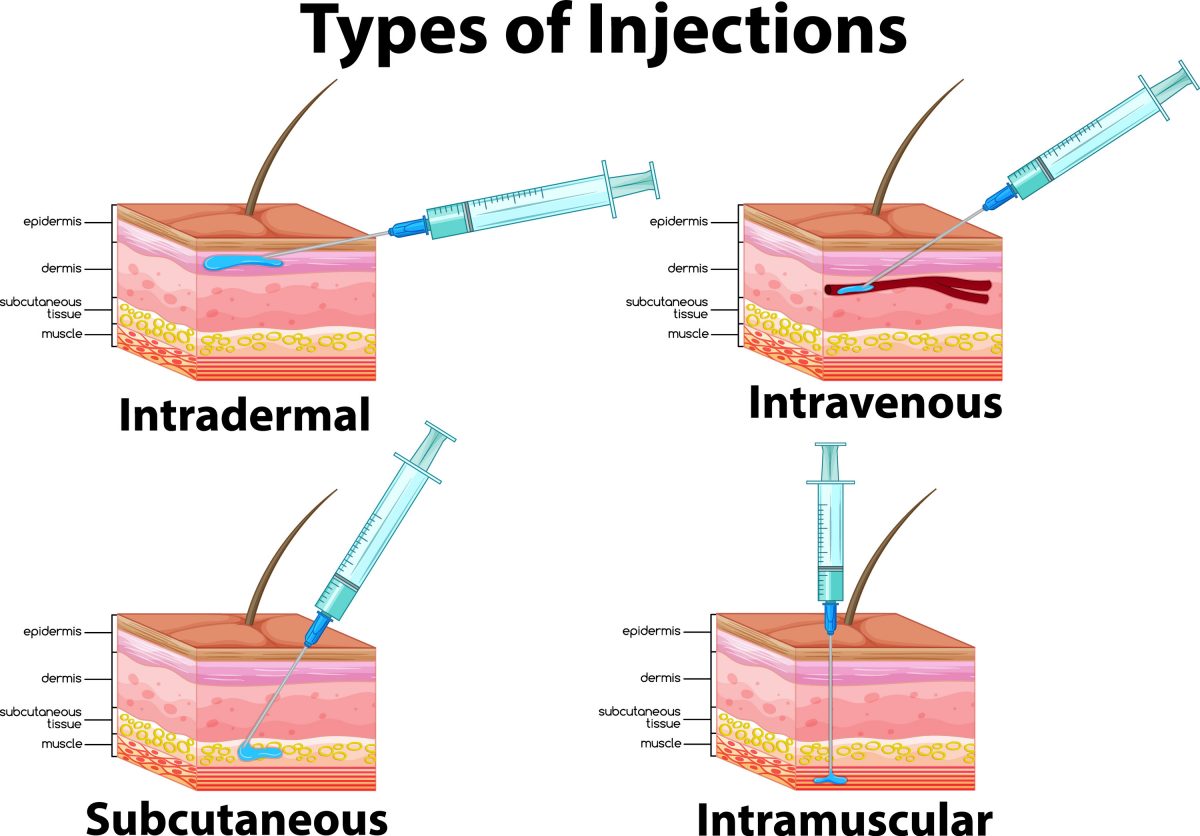

Intradermal administration occurs in the dermis just below the epidermis (see Figure 1).4 The epidermis—the thinnest layer—is made up mostly of epithelial cells, but also contains melanocytes (pigment-producing cells), Merkel cells (for light-touch stimuli), and Langerhans cells (tissue-resident macrophages).5 The dermis is a thicker layer containing cells of the adaptive and innate immune systems including macrophages, mast cells, Langerhans cells, and dermal dendritic cells. Cells of the dermis are essential in processing incoming antigens to decide if they are harmful and activate the immune system accordingly.5

Figure 1. Methods of Vaccine Administration

High levels of antigen-presenting cells in the dermis induce a more potent immune response, making this an attractive (and potentially superior) vaccination site.5,6 This significant reactivity in the dermis also prompts a strong immune response to a smaller quantity of vaccine antigen—as little as one-fifth to one-tenth the dose—compared to intramuscular or subcutaneous administration.5,7 For this reason, intradermal administration is dose-sparing and potentially cost saving.5 Intradermal administration also avoids the rare risk of nerve, blood vessel, or joint space injury.7

Clinical studies are evaluating intradermal delivery of other vaccines, but none are currently available in the U.S. aside from monkeypox under the recent EUA.5 In years past, an intradermal influenza vaccine was available, but the manufacturer stopped production after the 2017-2018 flu season for unknown reasons.8 Of all parenteral routes, intradermal injections have the longest absorption time due to the lack of blood vessels and muscle tissue in this area. This is attractive for sensitivity testing, as reactions are easier to visualize and assess for severity.4

While intradermal administration is more efficient and cost-effective, it requires more skill and practice compared to subcutaneous or intramuscular administration.9 If incorrectly administered, the vaccine may enter the subcutaneous tissue instead and be ineffective because the dose is too small.

INTRADERMAL ADMINISTRATION TECHNIQUE

The most common intradermal injection sites are the volar aspect (inner surface) of the forearm and the upper back below the scapula (shoulder blade).4 Intradermal injection is not the best choice for every patient. Skin should be free of lesions, rashes, moles, or scars that could alter visual inspection of the injection site (or interpretation of test results, when applicable).4 In the case of the monkeypox vaccine, intradermal administration is only authorized for patients 18 years or older without a history of keloids (thick, raised scars).10

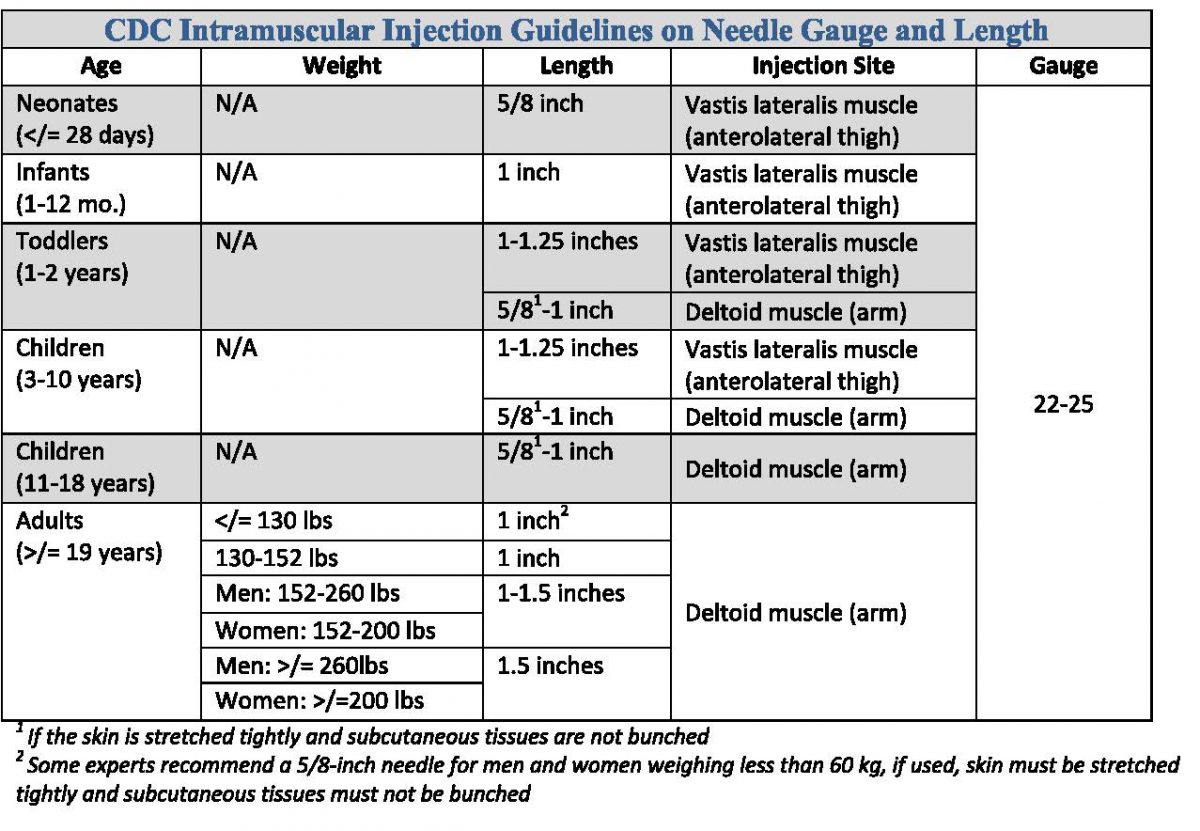

Researchers have developed various devices for intradermal drug delivery, but in the absence of specialized devices, individuals can employ the Mantoux technique using a hypodermic needle.5 The Mantoux technique is named for French physician Charles Mantoux who used this method for tuberculosis testing in the early 1900s.11 The optimum needle size for this method is 26 to 27 gauge and ¼ to ½ inch long.4

The Mantoux technique is new to pharmacists (we know because we could only find information about administration technique in nursing resources), so listen up, take notes, and remember that practice makes perfect4,10:

- Inspect the injection site and select an area that is free from lesions, rashes, moles, or scars. Avoid vaccination in an area where there is a recent tattoo (less than one month old). If tattoos cover both arms, select an area without pigment (ink) if possible. If the tattoo is unavoidable, administer through it.

- Clean the site with an alcohol or antiseptic swab using a firm, circular motion. Allow the site to dry completely to prevent alcohol from entering the tissue, which can cause stinging and irritation.

- Using the nondominant hand, spread the skin taut at the injection site. Taut skin provides easy entrance for the needle. This is especially important in older individuals with less elastic skin.

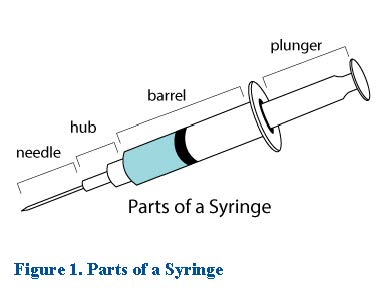

- Hold the syringe in the dominant hand between the thumb and forefinger at a 5- to 15-degree angle at the selected injection site with the bevel of the needle facing up.

- Place the needle almost flat against the patient’s skin and insert the needle into the skin no more than 1/8-inch (about 3 mm) to cover the bevel. Keeping the bevel side up allows the needle to smoothly pierce the skin and deliver the medication to the dermis.

- Once the needle is in place, use the thumb of the nondominant hand to slowly push the plunger to inject the medication.

- Inspect the injection site for a bleb (small blister) which should appear under the skin. The presence of a bleb indicates that the medication is correctly placed in the dermis. The bleb is desired but not required, so if it doesn't appear, don't panic. Simply adjust your technique for next time.

- Withdraw the needle at the same angle it was placed so as not to disturb the bleb and to minimize patient discomfort and tissue damage. Safely discard the syringe in a sharps container.

More visual learners can find a video demonstrating how to administer a vaccine intradermally at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dRsQf_UHsjs.

CONCLUSION

Vaccines work, that much we know. However, this is only true if they’re accessible, trusted, and used appropriately. Pharmacists can help promote access, education, and vaccine uptake if they have the knowledge and skills to do so. New vaccines and administration recommendations are challenging, but don’t let it get under your skin. We hope this quick-and-dirty overview of intradermal vaccines boosted your confidence and made it easier for you to give it a shot.

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

Only Skin Deep: The Pharmacist’s Guide to Intradermal Vaccine Administration

25-073 Posttest

Learning Objectives

• DISCUSS the potential benefits of intradermal vaccine delivery

• IDENTIFY how to administer intradermal injections

*

1. Which of the following is a benefit of intradermal vaccine delivery?

A. It can deliver a larger vaccine dose

B. It has the fastest rate of absorption

C. It avoids the risk of nerve injury

*

2. Which of the following makes the dermis a good site for vaccine administration?

A. High levels of Merkel cells

B. High levels of antigen-presenting cells

C. Low levels of Langerhans cells

*

3. About how far should you insert the needle to administer an intradermal injection via the Mantoux technique?

A. 1/8-inch

B. 1/4-inch

C. 1/2-inch

*

4. Travis Barker comes into your pharmacy asking for an intradermal vaccine. You inspect his forearms full of tattoos and find a small space without ink. You complete intradermal administration and notice a small bubble form under his skin. What does this mean?

A. You administered the vaccine subcutaneously

B. You administered the vaccine too close to a tattoo

C. You administered the vaccine correctly

*

5. Which of the following is appropriate technique for intradermal administration?

A. Insert the needle at a 5- to 15-degree angle with the bevel facing up

B. Pinch the skin between the thumb and forefinger of the nondominant hand

C. Remove the needle slowly at a 45-degree angle to reduce discomfort

Pharmacy Technician Post Test (for viewing only)

Only Skin Deep: The Pharmacist’s Guide to Intradermal Vaccine Administration

25-073 Posttest

Learning Objectives

• DISCUSS the potential benefits of intradermal vaccine delivery

• IDENTIFY how to administer intradermal injections

*

1. Which of the following is a benefit of intradermal vaccine delivery?

A. It can deliver a larger vaccine dose

B. It has the fastest rate of absorption

C. It avoids the risk of nerve injury

*

2. Which of the following makes the dermis a good site for vaccine administration?

A. High levels of Merkel cells

B. High levels of antigen-presenting cells

C. Low levels of Langerhans cells

*

3. About how far should you insert the needle to administer an intradermal injection via the Mantoux technique?

A. 1/8-inch

B. 1/4-inch

C. 1/2-inch

*

4. Travis Barker comes into your pharmacy asking for an intradermal vaccine. You inspect his forearms full of tattoos and find a small space without ink. You complete intradermal administration and notice a small bubble form under his skin. What does this mean?

A. You administered the vaccine subcutaneously

B. You administered the vaccine too close to a tattoo

C. You administered the vaccine correctly

*

5. Which of the following is appropriate technique for intradermal administration?

A. Insert the needle at a 5- to 15-degree angle with the bevel facing up

B. Pinch the skin between the thumb and forefinger of the nondominant hand

C. Remove the needle slowly at a 45-degree angle to reduce discomfort

References

Full List of References

References

REFERENCES

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Biden-Harris Administration Bolsters Monkeypox Response; HHS Secretary Becerra Declares Public Health Emergency. August 4, 2022. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/08/04/biden-harris-administration-bolsters-monkeypox-response-hhs-secretary-becerra-declares-public-health-emergency.html

2. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Monkeypox Update: FDA Authorizes Emergency Use of JYNNEOS Vaccine to Increase Vaccine Supply. August 9, 2022. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/monkeypox-update-fda-authorizes-emergency-use-jynneos-vaccine-increase-vaccine-supply

3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Notice of Amendment to the January 1, 2016 Republished Declaration under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act. October 3, 2022. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2022-21412.pdf

4. Administering intradermal medications. Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN). Accessed October 26, 2022. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingskills/chapter/18-4-administering-intradermal-medication/

5. Kim YC, Jarrahian C, Zehrung D, Mitragotri S, Prausnitz MR. Delivery systems for intradermal vaccination. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2012;351:77-112.

6. Hickling JK, Jones KR, Friede M, Zehrung D, Chen D, Kristensen D. Intradermal delivery of vaccines: potential benefits and current challenges. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89(3):221-226.

7. Brooks JT, Marks P, Goldstein RH, Walensky RP. Intradermal Vaccination for Monkeypox - Benefits for Individual and Public Health. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(13):1151-1153.

8. Influenza vaccine. Aetna Clinical Policy Bulletins. Reviewed August 1, 2022. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://www.aetna.com/cpb/medical/data/1_99/0035.html

9. Miller K. What Is an Intradermal Injection, the New Way the Monkeypox Vaccine Is Being Given? Prevention. August 12, 2022. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://www.prevention.com/health/health-conditions/a40869782/what-is-intradermal-injection/

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. JYNNEOS Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine:

ALTERNATE REGIMEN Preparation and Administration Summary (Intradermal Administration). Updated September 27, 2022. Accessed October 26, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/files/interim-considerations/guidance-jynneos-prep-admin-alt-dosing.pdf

11. Kis EE, Winter G, Myschik J. Devices for intradermal vaccination. Vaccine. 2012;30(3):523-538.