INTRODUCTION

"Imagine if you're [at a] truck stop, you take two bottles of that and you're driving down the road — now you're high on opioids.”1 Researcher Todd Hillhouse.

The commentator above is not referring to a product purchased from a seedy individual at the rear of the parking area, but rather something purchased out in the open, off the shelf of the public retail outlet prominently located within the rest area. Can it possibly be true that the public can purchase a product that mimics opioids at a truck stop or convenience store or online, no questions asked? Not only does the drug allegedly produce a “high,” It’s been associated with increasing reports of serious adverse events and addiction.2 Shouldn’t the FDA or DEA have regulations in place to prevent this from occurring?

The drug in question is tianeptine, colloquially referred to as “Gas Station Heroin,” and is only one of several examples of a commodity that poses a danger to the public but falls between the cracks of regulatory oversight.

Pharmacists are accustomed to dispensing prescription drugs that have undergone rigid clinical testing and been approved by the United States (U.S.) Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, many products face less stringent requirements (e.g., over the counter [OTC] drugs, supplements) and some may receive no approval whatsoever. This activity will compare the regulatory standards for several categories of consumer products with an emphasis on substances that circumvent regulatory review.

DRUG APPROVAL

Generally, a drug will undergo some level of review before it makes it way to the public. However, the rigor of the scrutiny varies greatly depending on the nature of the drug.

As you are no doubt aware, prescription drugs on the market have been reviewed by the FDA which assesses evidence that the drug is safe and effective.3 The FDA's Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) evaluates evidence submitted by the manufacturer to ensure that drugs, both brand-name and generic, are effective for the target condition and that their health benefits outweigh their known risks.3 This is a structured process and generally requires at least two clinical trials. Approved drugs are also subject to post-market surveillance to ensure that they continue to be safe.3

The FDA also has several accelerated approval mechanisms that expedite the marketing of promising prescription therapies that treat serious or life-threatening conditions and provide therapeutic benefit over available therapies. Many drugs have been approved under these programs and have altered the course of treatment since these pathways were developed in 1992, including antiretroviral drugs used to treat HIV/AIDS and targeted anti-cancer agents.3

During the COVID pandemic, pharmacists became familiar with another modified drug approval mechanism, emergency use authorization (EUA).4 If the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) declares a public health emergency, the FDA may authorize the emergency use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products.

The FDA was granted authority to issue EUAs in 2004 when Congress passed the Project BioShield Act. That Act was intended to facilitate the development, procurement, and use of medical countermeasures against chemical, biological, radiologic, and nuclear terrorism agents.5 The Act was passed in response to the events following the terrorism episode on 9/11; although the intent was to protect against acts of terrorism, to date the only EUAs issued have been in response to pandemics. Medical products considered for an EUA undergo FDA review, but the standard used for approval is a lower level of evidence (“reasonable to believe that the product may be effective” rather than “effective”) than needed for full FDA approval.4 There also must be no adequate, approved, and available alternative to the candidate product for diagnosing, preventing, or treating the disease or condition.4 (“Unavailable” includes insufficient supplies of the existing product to meet the emergency while inadequate includes contraindications for special circumstances or populations, for example children.4)

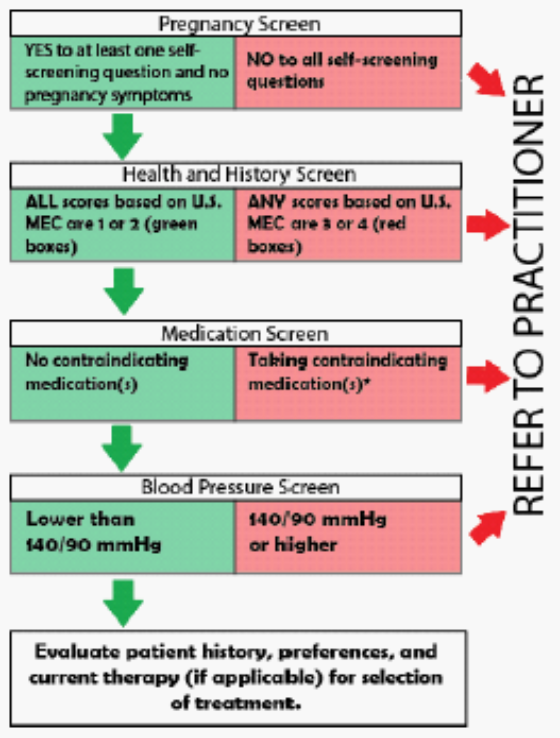

Readers will be spared from a detailed review of the drug approval process, since pharmacists probably heard this numerous times while in school, but it is an important reminder that non-prescription compounds do not undergo the same rigorous pre-market evaluation by the FDA. OTC drugs are also approved by the FDA, but under different criteria. The primary difference is that the approval of prescription drugs requires approval of a specific drug product to treat a specific condition. Conversely, most OTC products must only conform with existing OTC monographs that describe the marketing standards including the active ingredients, labeling, and other general requirements.6

OTC monographs set the conditions under which OTC drug products are generally recognized as safe and effective for their intended use. A monograph covers active ingredients, dosages, formulations, and labeling claims; a new OTC product does not need FDA approval if its manufacturer complies with the relevant monograph. This is because the FDA had already evaluated the safety and effectiveness evidence as part of its monograph rulemaking process.6 However, the FDA assesses monograph compliance as part of its inspection process.7

If it is a new OTC product without an existing monograph, the manufacturer must submit a New Drug Application (NDA) with clinical trial data demonstrating safety and effectiveness.7

In addition, the sponsor must provide consumer behavior studies demonstrating that purchasers can use the nonprescription drug product safely and effectively without the supervision of a healthcare provider.7 Of course, a prescription drug may also become an OTC drug.8

In stark contrast, oversight of supplements is much less rigorous. Dietary supplements are not subject to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA Act), but rather are regulated by a different law, the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA). DSHEA, enacted in 1994, states that “the Federal Government should not take any actions to impose unreasonable regulatory barriers limiting or slowing the flow of safe products and accurate information to consumers.”9 A dietary supplement is defined as a vitamin, mineral, amino acid, herb or other botanical, or a dietary substance for use by man to supplement the diet by increasing the total dietary intake.9

Unlike drugs, supplements are not subject to pre-market FDA approval.10 (Hence the disclaimer found on supplement labels [“This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration."]). The manufacturer does not have to provide the FDA with the evidence it relies on to substantiate safety before or after it markets its products. However, if a proposed dietary supplement contains a new dietary ingredient, the manufacturer must submit a notification to the FDA 75 days before introducing it to the market. The notice must include information on the basis of which the firm has concluded that the supplement will reasonably be expected to be safe.10 (Only a notice is required, the FDA does not evaluate the data.)

Manufacturers and distributors have the initial responsibility for ensuring that their dietary supplements meet the safety standards for dietary supplements. In general, the FDA’s ability to take action is limited to postmarket enforcement.11 Manufacturers and distributors must record, investigate, and forward to FDA any reports they receive of serious adverse events associated with the use of their products.

The FDA cannot conduct post-market research on supplements to corroborate a manufacturer’s claims. It can only issue warning letters asking manufacturers to voluntarily recall adulterated or misbranded products. If a manufacturer refuses to voluntarily recall its product, the burden is on the FDA to prove that the supplement is harmful or adulterated.11 The FDA must show that the dietary supplement has a significant or unreasonable risk of causing injury or illness, a very high bar. In addition to issues of safety, problems exist with respect to the purity and bioavailability of some products.11

Supplement manufacturers do have restrictions on the types of claims they can make. They may not claim to diagnose, mitigate, treat, cure, or prevent a specific disease or class (which would make them a drug, hence the second part of the label disclaimer: “This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease”) but may claim to aid a structure or function of the human body, benefit a classical nutrient disease, or promote general well-being.10

PAUSE AND PONDER: Should supplements be subject to more stringent regulations and if so, in what ways?

IF I’M NOT A DRUG NOR A SUPPLEMENT, WHAT AM I?

Despite all these regulatory pathways providing some degree of control, products can wind up being available for retail sale without any oversight. As noted above, an example of this is tianeptine, which is not FDA-approved, is not generally recognized as safe for use in food, and does not meet the statutory definition of a dietary ingredient. It is, nevertheless, commonly available from retail outlets.12

“Gas Station” Drugs

A growing number of substances are available from gas stations, convenience stores, bodegas, vape shops, and even the Internet; they may even be purchased by minors.13 They have been given the label “gas station” drugs.

It is believed that the first instance of a “gas station” drug was the emergence of “Spice,” a synthetic cannabinoid (producing cannabis-like effects) in 2008.13 The drugs were sold under the guise of being herbal incense or potpourri to circumvent the approval process; the FDA eventually placed the drugs in Schedule I in 2011. A similar pattern was seen a few years later with synthetic cathinones being sold as “bath salts” with “warnings” that they were for external use only, even though testimonials clearly indicated that they were being taken internally. (Cathinone is a naturally occurring beta-ketone amphetamine analogue from the leaves of the Catha edulis plant. Synthetic cathinones derivatives may possess both amphetamine-like properties and the ability to modulate serotonin, causing distinct psychoactive effects.) The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) eventually banned them after a series of fatalities occurred.13 Typically, substances like these continue to be sold until their dangerous consequences are recognized and there are calls to restrict them.13

Some examples of unregulated drugs available today include delta 8/10 tetrahydrocannabinol, Royal Honey, and Rhino which contain sildenafil, tianeptine, kratom, and phenibut.13 The latter three substances will be discussed more fully below.

PAUSE AND PONDER: What would you do if someone asked, “Does the pharmacy sell (one of the gas station drugs)”?

Tianeptine

One of the newer emerging gas station threats is the sale of products containing tianeptine.14 Tianeptine was synthesized in France in 1971 as an analog of the newly discovered tricyclic antidepressants. It was approved in France as an antidepressant in 1989 and is now available in more than 60 countries.13,15

Tianeptine [(7-((3-chloro-6-methyl-5,5-dioxido-6,11-dihydrodibenzo[c,f][1,2]thiazepin-11-yl)amino)heptanoic acid)] is an atypical tricyclic antidepressant approved in some European, Asian, and Latin American countries primarily for the treatment of major depression. It has also been used to treat anxiety and irritable bowel syndrome.13 Unlike traditional tricyclics which block serotonin reuptake in the CNS, tianeptine actually increases serotonin uptake.13 However, it is now believed that its antidepressant activity is related to modulating glutamate-mediated pathways involved in neuroplasticity (a process that involves adaptive structural and functional changes to the brain; in other words, the brain's ability to absorb information and evolve to manage new challenges).15 Unlike conventional tricyclic antidepressants, tianeptine is not primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450s, but is largely metabolized by β–oxidation (which would be a consideration with regard to potential drug interactions).15

More significantly for the purpose of this activity, tianeptine acts as a full agonist at the mu-opiate receptor and a weak agonist at the delta-opioid receptor.13,14 It is moderately potent but highly efficacious as a mu agonist.15 As such, it causes opiate-like euphoria and carries a significant risk of overdose.13 Moreover, it has a short half-life that can lead to rapid withdrawal, increasing its potential for addiction and misuse.13 Some of the countries where tianeptine has been approved to treat depression and anxiety have restricted how tianeptine is prescribed or dispensed, or warned of possible risk of addiction.13

In the U.S., tianeptine is not an approved prescription drug, but has become more visible as an OTC product sold in retail stores under the names of ZaZa Red, Tianna Red, Neptune’s Fix, Pegasus, TD Red, and others.12 The drug has earned the nickname “gas station heroin” due to its opioid-like effects and potential for similar abuse.12

U.S. law enforcement has encountered tianeptine in various forms, including bulk powder, counterfeit pills mimicking hydrocodone and oxycodone pharmaceutical products, and individual stamp bags (small wax packets commonly used to distribute heroin).14 Tianeptine has also been combined with antidepressants and antianxiety medications; patients often combine the drugs themselves, and some manufacturers make fixed-dose combinations.14

Tianeptine-containing products available to consumers include some with high doses and are making dangerous and unproven claims that tianeptine can improve brain function and treat anxiety, depression, pain, opioid use disorder, and other conditions.12 Case reports in the medical literature describe U.S. consumers ingesting daily doses on the order of 1.3 to 250 times (50 mg to 10,000 mg) the daily tianeptine dose typically recommended in labeled foreign drug products.12

Risks

Reports of adverse reactions and adverse effects involving tianeptine have been increasing in the U.S.16 Poison control centers have reported that cases involving tianeptine exposure increased nationwide, from 4 cases in 2013 to nearly 350 cases in 2024. From 2020 to 2022, more than 600 calls were made to poison control centers after exposure, and five deaths occurred as a result.16

The FDA has identified cases in which consumers have experienced serious harmful effects from abusing or misusing tianeptine including agitation, drowsiness, confusion, sweating, rapid heartbeat, high blood pressure, nausea, vomiting, slowed or stopped breathing, coma and death.16 Naloxone is an appropriate countermeasure in cases of severe poisoning, since tianeptine has opioid effects.13 Users frequently consume tianeptine chronically and, if they stop tianeptine abruptly, they may experience withdrawal symptoms similar to those associated with opioid discontinuation (e.g., craving, sweating, “goose flesh,” diarrhea, myalgias).16 Tolerance and dependence appear to develop quickly.17 Severe withdrawal symptoms in humans that have led to hospitalization following the use of tianeptine have also been reported.12,16

Like many drugs of this nature, tianeptine is frequently found combined with other illicit ingredients, often synthetic cannabinoids, which are not included on the product label.17 Poison control centers describe the signs of overdose to vary widely and include clamminess, nausea, low blood pressure, and unconsciousness as well as seizures and severe stomach cramps.17

It is difficult to get an accurate picture of the extent of tianeptine abuse. Reports to poison control centers are voluntary and hospitals do not test for it, so its prevalence is likely underreported.17 The drug also has a strong following on social media where its merits are hotly debated with one social media forum called “Quitting Tianeptine” attracting more than 5,000 followers.17

Regulation

Clearly, tianeptine is not an FDA-approved medication. Could its sale at convenience outlets be justified as being designated a dietary supplement and therefore an appropriate consumer product covered by DSHEA? The FDA says it does not meet the statutory criteria for a dietary supplement.18

Therefore, in the FDA’s view, “It is an unsafe food additive, and dietary supplements containing tianeptine are adulterated under the FD&C Act” (i.e., not “legal”). Nevertheless, many tianeptine products, frequently of non-U.S. origin, are openly marketed as supplements with many consumers mistakenly believing that it is a safe alternative to street opioids.17

FDA Action

In May 2025, the FDA issued warnings to consumers about the “dangerous and growing health trend facing our nation” about the increasing number of adverse events, including death, associated with tianeptine-containing products.12 The agency warned consumers not to purchase or use any tianeptine product due to serious risks. The agency also issued warning letters to companies distributing and selling tianeptine products and issued an import alert to help block shipments to the U.S.19 However, its sale is not restricted.

Several states have taken steps to limit sales of these products. Some states have placed tianeptine on controlled drug schedules.20 At least eight states (AL, FL, GA, IN, KY, MN, OH, VA) classify tianeptine as a C-I drug. Five others (AR, MI, NC, OK, TN) have placed it in C-II and Mississippi considers it a C-III substance. Other states have similar restrictions under consideration.20

Increasing the control of tianeptine is also being discussed at the federal level. In 2024, members of Congress wrote to the FDA urging them to take steps beyond the issuing of warnings, stating that they believed that “more action on tianeptine use is needed to ensure the health and well-being of the American people.”21 There is a bill pending in Congress that would place the drug in C-III.22

A more recent Congressional proposal would ban the sale of tianeptine entirely.23 It remains to be seen if additional regulation becomes a reality.

KRATOM

Tianeptine is not the only product to exist in a regulatory gray area. Another example with a long history of regulatory wrangling is kratom.24 Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa korth) is a tropical tree indigenous to regions of Southeast Asia (Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar) and belongs to the same family as the coffee tree.25 Traditionally, Thai and Malaysian laborers and farmers chewed the leaves to relieve fatigue. It has also been used as a substitute for opium when opium is unavailable and chronic opioid users have used it to manage opioid withdrawal symptoms.25 Soldiers returning from the Vietnam war and immigrants from Southeast Asia introduced kratom to America.26

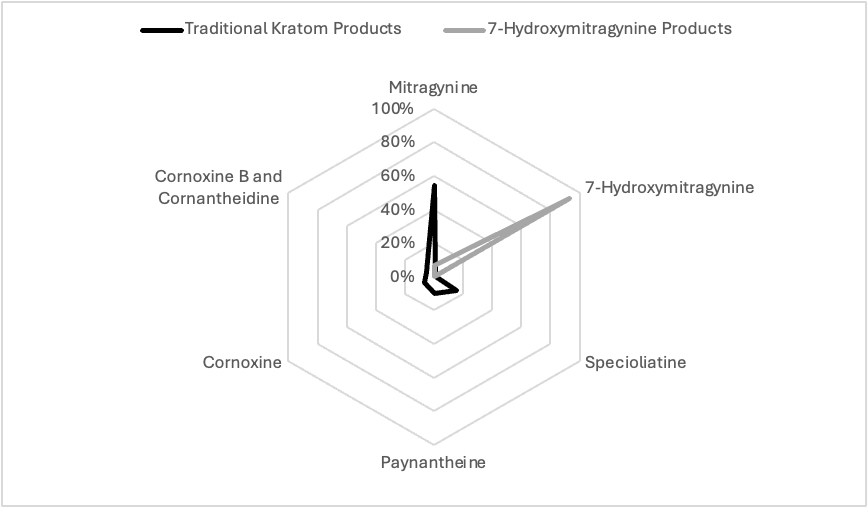

The principal constituents of Kratom, mitragynine (MTG) and 7-hydroxymitragynine (7-HMG), have opioid receptor activity.25 These compounds are indole alkaloids structurally related to yohimbine and have shown anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity in experimental animals.27

MTG and 7-HMG both bind to the human opioid receptors with nanomolar affinity; they function as partial agonists at the mu-opioid receptor and weak antagonists at kappa-opioid and delta-opioid receptors.27

7-HMG exhibits approximately 5-fold greater affinity at the mu-opioid receptor compared to MTG. In rats, MTG does not exhibit abuse liability and decreases the reinforcing effects of morphine. On the other hand, 7-HMG demonstrates abuse liability and increased morphine self-administration.27 MTG can be converted to 7-HMG both in vitro and in a mouse model. It is likely that at least some of the activity attributed to kratom may be due to its metabolic conversion to 7-HMG.27 It has been suggested that individuals who self-administer kratom tea to treat pain, addiction, or depression might achieve very different results depending on the alkaloid profile of the product that they use.27 If so, it would be difficult for consumers to predict the magnitude of activity to expect from ingesting the product since the product labeling does not reflect the variability in alkaloid content .27

Kratom produces both stimulant and sedative effects. At low doses, kratom produces stimulant effects, with users reporting increased alertness, physical energy, talkativeness, and sociable behavior, while high doses produce opioid effects including sedation and euphoria.25 Effects occur within five to 10 minutes after ingestion and last for two to five hours.

The most significant issue with products labeled “kratom” is the introduction of high concentrations of a metabolite (7-HMG) as the most abundant alkaloid. The most abundant alkaloid in traditional kratom products is mitragynine, with concentrations ranging from 54% to 66% of the total alkaloid content. Many other alkaloids comprise the remaining 34% to 46% of total alkaloids, but 7-HMG only constitutes less than 1% of the total. In its natural, fresh state, kratom leaves do not contain 7-HMG. “Kratom” products, often enhanced with extra 7-HMG, are available from Internet sites where it is promoted as a legal psychoactive product.25 Website entries include listings of vendors, methods of preparation, user experiences, and alleged medicinal uses.25 Kratom products are commonly sold in powder form, which is bitter, and users typically consume it as a capsule or use the powder to make tea.26 Common uses are as an alternative to prescription opioids for pain, self-management of opioid or other substance use disorder (including easing withdrawal symptoms), or treating anxiety and depression.25,26 Reports of adverse effects have increased as the drug has become more popular, with more frequent admission to a healthcare facility and serious medical outcomes, such as seizure, respiratory distress, or slow heart rate.26 According to data from the FDA's adverse event reporting system, mitragynine was involved in 1,255 cases from 2008 to September 2024 of which 1,171 cases were classified as serious and 637 cases resulted in death.25

Regulatory Actions

The risks associated with kratom have prompted government officials to try to restrict its sales for almost a decade, but these efforts have been largely unsuccessful. In 2016, the DEA published its intent to temporarily place MTG and 7-HMG into Schedule I.28 (The Controlled Substances Act empowers the Attorney General to temporarily place a substance into Schedule I for two years without regard to other administrative requirements if there is a finding that such action is “necessary to avoid an imminent hazard to the public safety.”) This decision was based, in part, on the DEA’s finding that the “severity of the reported outcomes, health effects, and increased use of kratom suggests an emerging public health threat.”28 Organizations promoting kratom use did not receive this decision favorably.24,26

Shortly after the DEA published its notice of intent, a “March for Kratom” was organized at the White House and the protests convinced 51 members of Congress on both sides of the aisle to sign a letter disagreeing with the DEA’s decision.26 Kratom supporters also sent a petition containing more than 145,00 signatures opposing the DEA’s decision to President Obama.26

Kratom advocates stressed several points. They disputed the DEA’s claim about the magnitude of the harm that the substance was producing and also cited reports of possible beneficial effects of kratom as a useful alternative to opioids in managing pain and treating opiate addiction. They maintained that kratom is safer than prescription opioids and that the deaths associated with kratom could be due largely to the simultaneous use of other substances.26 Supporters also posted numerous online testimonials from users touting kratom’s beneficial effects.26

As a result of the backlash, the DEA withdrew the proposed action less than two months after the initial publication, citing numerous comments from the public. The DEA initiated a period of public comment on the scheduling recommendation and received over 23,000 comments with 99% of them opposing the ban.26

A year later, the FDA renewed its effort to schedule the kratom alkaloids and submitted an “eight factor” analysis to the DEA (see the SIDEBAR).26 A month later, the FDA announced a public health advisory on kratom and supported stricter regulation by asserting that kratom was associated with 36 deaths and has similar effects and dangers to other opioids. This was followed by a recall based on contamination of samples with Salmonella or heavy metals.26 However, its legal status has remained unchanged.

SIDEBAR: DEA 8 Factor Test

In determining into which schedule a drug or other substance should be placed, or whether a substance should be decontrolled or rescheduled, certain factors are required to be considered by the Controlled Substances Act [21 U.S.C §811(c) ].29 These are

- Its actual or relative potential for abuse.

- Scientific evidence of its pharmacological effect, if known.

- The state of current scientific knowledge regarding the drug or other substance.

- Its history and current pattern of abuse.

- The scope, duration, and significance of abuse.

- What, if any, risk there is to the public health.

- Its psychic or physiological dependence liability.

- Whether the substance is an immediate precursor of a substance already controlled under CSA.

In 2021 the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that it would conduct a review of kratom as part of its role in making public health recommendations to the international community. The FDA participated in this process by submitting information, although two U.S. Senators urged the agency to oppose any effort to add kratom to the list of internationally controlled substances.26 Ultimately, the Committee concluded that there is insufficient evidence to recommend a critical review of kratom.30

The controversy over kratom has not abated, however. In 2023, bills were introduced in both houses of Congress to “protect access to kratom.”26,31 The bills did not expressly address the legal status but would require the HHS Secretary to hold at least one public hearing to discuss the safety of kratom products. Significantly, if enacted, the law would prohibit HHS from imposing requirements on kratom that are more restrictive than those for foods or dietary supplements.26,31 It would still permit states to impose more restrictive laws.

More recently, in July 2025, the FDA recommended that products with concentrated levels of 7-HMG be classified as C-I substances; the press release does not define concentrated and the warning only refers to "added" 7-HMG.32 This would apply to products containing high levels of 7-HMG in tablets, gummies, drinks, or parenteral, but not plant, products. FDA Commissioner Makary called the move an “effort to prevent another ‘wave of the opioid epidemic’” from blindsiding the country.”32

Most states permit the sale, possession, and consumption of kratom, although some set limits.26 There are age restrictions on the sale or possession of kratom products in 18 states; seven of the states restrict the distribution kratom to individuals 18 years of age or older while the other 11 states set an age restriction of 21.26 Tennessee had banned kratom completely, but changed its law to permit natural forms of kratom to be used by individuals over the age of 21.33 Other states have labelling requirements on kratom products.26,34 For example, South Carolina passed a law in 2025 mandating that labels must provide details on alkaloid content, serving sizes, and include FDA disclaimers and age warnings. Violations incur civil penalties up to $2,000.34

Some states have taken more aggressive steps to limit access to kratom. Michigan became the first state to ban sales of the drug, classifying it as a Schedule II controlled substance in 2018.1 As of April 2025, 24 states and the District of Columbia regulate kratom products in some manner.26 Seven states (AL, AK, IN, MI, RI, VT, and WI) and the District of Columbia, treat kratom’s psychoactive components as controlled substances.26

Seven states (AL, AR, IN, LA, RI, VT, WI) effectively ban the sale of kratom by classifying both the plant material and the psychoactive alkaloids as a controlled substance.33,34 Most have defined it as a C-I substance. Louisiana passed its law in August 2025 classifying the active ingredients, kratom products, and the Mitragyna tree as Schedule I controlled substances. Penalties are severe; producing or distributing kratom can lead to fines up to $50,000 and one to five years in prison, while possession incurs fines up to $1,000 or six months in jail for repeat offenses.34

Other states have enacted more consumer-focused kinds of controls.34 For example, Hawaii requires products to be registered with the Department of Health, have third-party lab testing, and comply with federal good manufacturing practices. Products may not exceed 2% 7-HMG, contain harmful substances like synthetic cannabinoids, or be designed to attract children (e.g., cartoon-shaped products).34 Mississippi requires retailers to obtain permits and imposes an excise tax of $2.50 per ounce for kratom leaf and $5.00 per ounce for extracts.34 Four states (AZ, GA, OK, UT) require that labels indicate the alkaloid content of the product.34

PAUSE AND PONDER: Where should the line be drawn between protecting the public and patient autonomy?

PHENIBUT

Phenibut, known colloquially as Phenigamma and Phenygam among others, is another substance that has evaded regulatory control. Phenibut is a derivative of gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA) and acts as a GABA mimetic primarily at GABA-B receptors (like baclofen); it also affects GABA-A receptors but to a lesser extent. It also stimulates dopamine receptors and antagonizes beta-phenethylamine (PEA), a putative endogenous anxiogenic transmitter.35 Both its desired and adverse effects appear similar to other GABA receptor modulators like benzodiazepines.36

It was originally developed in the former Soviet Union in the 1960s to relieve anxiety and improve cognitive function in military personnel.37 Later it was introduced into clinical medicine as a treatment for anxiety, insomnia, and various psychiatric conditions ranging from post-traumatic stress disorder to alcohol withdrawal. It has also been used to enhance cognition in young adults and to delay dementia in the elderly. Its presence has expanded to other parts of Europe and the U.S. where it is marketed as a putative OTC cognition enhancer.37 The drug is available in different forms including as a powder, “fine crystals,” and capsules and is also found combined with other substances.37,38

Phenibut produces a number of adverse effects including drowsiness, lethargy, agitation, tachycardia, and confusion.37 In addition, it can lead to the development of tolerance and dependence and withdrawal may manifest as a severe abstinence syndrome that may require medical intervention.37 The abstinence syndrome resembles benzodiazepine withdrawal and patients may experience insomnia, anger, irritability, tremulousness, decreased appetite, and heart palpations.38 Phenibut also has the potential for interactions with related substances such as anxiolytics, antipsychotics, sedatives, opioids, and anticonvulsants.37

During the period from 2009 to 2019, U.S. poison centers received 1,320 calls about phenibut exposures from all 50 states and the District of Columbia.39 The most commonly reported adverse health effects included drowsiness or lethargy, agitation, tachycardia, and confusion. Coma was reported in 6% of cases. In half of the cases, the exposure resulted in moderate effects with no long-term impairment. About 12% of cases reported life-threatening effects or resulting in significant disability, with three deaths.39 Physical dependence, withdrawal, and addiction have also been reported.38

The FDA issued warning letters to companies whose products contained phenibut and were marketed as dietary supplements as far back as 2019. The FDA concluded that phenibut does not meet the statutory definition of a dietary supplement, and the products were therefore misbranded.40 Yet, phenibut is still legally available for sale in the U.S., largely through online sources.

Phenibut has become increasingly available in the U.S. (and European) market, often labelled as a dietary supplement with claims such as promoting focus, relaxation, and positive mood; improving memory and concentration; counteracting irritability and restlessness; and increasing libido.37 Studies of consumers have found that it is frequently purchased as a therapeutic substitute for benzodiazepines, and to manage withdrawal due to benzodiazepines, opioids, and alcohol.37 Nevertheless, the FDA does not regard it as a dietary ingredient and considers phenibut-containing supplements declaring themselves as a dietary ingredient misbranded under the FDCA.

The agency sent warning letters to at least three companies that have marketed products containing phenibut labelled as dietary supplements in 2019. Despite the warnings, the quantity of phenibut increased in three of four brands of OTC phenibut supplements tested following the FDA’s action; in some cases, the amounts detected were 450% greater than a typical 250 mg pharmaceutical tablet manufactured in Russia.41

The warnings were obviously ineffective and phenibut remains readily available in the U.S., largely online.42 Several European countries have made phenibut a controlled substance. In the U.S., Alabama made phenibut a Schedule II drug in 2021and additional states are considering legislation to classify it as a controlled substance.42

PEPTIDES

Another means used to circumvent FDA regulations is to sell drugs on-line advertised as “research compounds” or “lab use” although the promotional material and product reviews clearly show they are being used by individuals who are not enrolled in drug trails. These compounds are readily available online, including through Amazon.com.43

There is a high demand for “research” compounds labelled as “peptides” especially among individuals seeking substances for athletic performance enhancement, improved libido, anti-aging effects, or weight loss (pseudo or real GLP-1 drugs).44 This includes existing prescription drugs purchased online through clandestine overseas operations or true research compounds. One example is sermorelin, which modulates the release of growth hormone and allegedly increases muscle mass and possibly enhances libido.44 The high demand has led to shortages of prescription products, further stimulating illicit sales.44

FINAL COMMENTS

While most therapeutic substances are subject to some degree of control by the FDA, some products available in retail stores or on-line receive no regulatory approval. They present a risk to the public. Manufacturers of these substances may try to circumvent regulation by falsely depicting them as dietary supplements, research compounds, or for external use. Consumers may use these to self-manage their medical conditions or for recreational purposes with a risk of developing serious adverse effects or dependence. The FDA has tried to limit the use of these substances by issuing warnings to consumers and warning letters to manufacturers, but these tactics have had limited success. Pharmacists should be prepared to answer questions about these drugs which commonly gain momentum through social media and should point out that there is no oversight over their claims or safety.