Learning Objectives

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

| · DEFINE different types of bias and how they are formed |

| · RECOGNIZE what bias may look like in the pharmacy setting |

| · IDENTIFY how bias can impact patient care |

| · APPLY methods to address and mitigate bias in the workplace |

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to:

| · DEFINE different types of bias and how they are formed |

| · RECOGNIZE what bias may look like in the pharmacy setting |

| · IDENTIFY how bias can impact patient care |

| · ILLUSTRATE methods to address and mitigate bias in the workplace |

Release Date: March 20, 2024

Expiration Date: March 20, 2027

Course Fee

FREE

There is no funding for this CE.

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-24-017-H04-P

Pharmacy Technician: 0009-0000-24-017-H04-T

Session Codes

Pharmacist: 24YC17-TKF38

Pharmacy Technician: 24YC17-FTK43

Accreditation Hours

2.0 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-24-017-H04-P/T will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Jessica Bylyku

PharmD Candidate 2024

UConn School of Pharmacy

Storrs, CT

Jeannette Y. Wick RPh, MBA, FCCP

Director Office Pharmacy Professional Development

UConn School of Pharmacy

Storrs, CT

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Neither Ms. Wick nor Ms. Bylyku have any relationships with ineligible companies.

ABSTRACT

Implicit bias is an important buzzword in healthcare. It has received much attention in the past few years because many researchers have documented its pervasive existence among healthcare providers. Implicit bias involves consciously or unconsciously thinking of some patient groups (or some coworkers) as less important than others, less deserving of care, or simply “less than.” Related concepts include second victim phenomena and imposter syndrome. Good research documents that many people from disenfranchised groups experience implicit or explicit bias when they visit pharmacies. Educational institutions have started to develop programs to educate pharmacists about potential implicit bias before they graduate. Yet most pharmacy personnel who work in clinical contexts have not had such education and need to understand the basic concepts of implicit bias. Pharmacy staff who take time to examine their own attitudes can improve care in influential ways and become significantly more enlightened. This continuing education activity provides basic education on implicit bias and refers readers to evaluation tools.

CONTENT

Content

INTRODUCTION

Can you solve this riddle?

A father and son are involved in a car crash. The son is rushed to the hospital. As the son is about to enter surgery the surgeon says, “I can’t operate—that boy is my son!”

People answer this question in a variety of ways, revealing different implicit biases. Some answers include 1) the boy has two fathers or 2) the father was actually a priest or 3) the whole thing was a dream. Researchers asked this question to two focus groups, one consisting of 197 college students from Boston University and the other, 103 children from Brookline Summer camps.1 Only 14% of college students and 15% of children answered correctly with the “mom’s the surgeon."1 A majority of people didn’t guess that the surgeon was the boy’s mother until a few tries, revealing the implicit bias that females are not meant to be doctors or surgeons.

TYPES OF BIAS

Implicit biases are unconscious mental processes that create unintentional automatic associations and reactions.2 Implicit bias is more than a stereotype, which is a fixed set of characteristics associated with a particular social group. Implicit bias occurs when people harbor biases unconsciously. A person can develop negative feelings or attitudes towards another person by failing to connect to another person’s identities. The other person may then become part of an “out-group.”2 This is not to say that those with shared identities hold no bias towards each other; some women think that women cannot be surgeons, for example. It’s important to look at other factors that cause implicit bias. Besides obvious differences in identities, social norms can influence biases and media outlets, public policy, and even education may magnify bias.2 People may not often express implicit biases out loud because of their hidden, unconscious nature. Implicit biases contribute to a person’s explicit biases.

Explicit biases include peoples’ conscious preferences, beliefs, and attitudes, and people may communicate them outright.2 For example, people may express explicit biases verbally and expose their prejudicial opinions. Prejudice—a biased response towards a social group and its members based on preconceptions3—may lead to irrational hostility directed towards an individual or group.

In-Group vs Out-Group

Social psychologists have long known that people define themselves in terms of social groups and often malign or disparage others who don't fit into their social groups. People who are part of the “in-group” feel they belong to that group because of social perceptions. People part of the in-group generally have positive views of each other and perceive that the group is composed of individual people.4 In direct comparison, in-group members view people in the “out-group” negatively because they do not belong to the in-group. People in the in-group characterize the out-group as a homogeneous collective rather than individuals. Thus, it becomes easy for members of the in-group to label the out-group as “all the same” rather than treat them like individuals.4

Simply put, in-vs-out group labeling becomes a case of “us-vs-them" with those in the in-group being “us” and those in the out-group being “them.”4 This tendency explains why hostility can exist between certain groups based on factors like political parties, race, or sexual orientation. This concept of “othering” people is fundamental to understanding how bias can influence personal opinions. Healthcare workers must be mindful of their opinions to ensure biases do not interfere with patient care.

Differentiating Stereotypes, Microaggressions, and Discrimination

Stereotypes are a fixed set of attributes associated with a particular group.2 Stereotypes are often untrue or unfair generalizations about people who may appear or identify a certain way. Stereotypical beliefs can lead to displays of microaggression, discrimination, and harmful judgment. Some common examples of stereotypes include

- People who wear glasses are smart

- Boys are stronger than girls

- People with tattoos are dangerous

- Men are better drivers than women

Microaggressions are physical or verbal acts that subtly express stereotypical thoughts. A 2010 study tracked high school students (N = 342) over their four-year progression and found that students had experienced 21 different types of microaggressions at least once.5 Some examples of reported microaggressions included5

- Teachers assuming a Black student was poor or illiterate

- Hispanic and Asian students were asked to teach “native words” even if they only spoke English

- Students of color being called on to speak on behalf of their race

Discrimination is the result of implicit or explicit biases. It causes unfair treatment of individuals and communities based on general policies, practices, or norms.2

PAUSE AND PONDER: What kinds of implicit bias have you observed in your workplace?

Consider this example: Kate was shopping at the rear of a beauty store when suddenly, someone robbed the cashier located at the front of the store. She rushed home and immediately called her friends Mark and Sylvia to share what she had experienced. Mark asked what the robber looked like. Sylvia says, “I didn’t see him. He was probably Black. They usually are.” This demonstrates a stereotype about Black people. Her comments are the microaggressions in this case. Sylvia’s racial bias is what contributed to this reaction.

BIAS SUBGROUPS

Bias comes in many forms and is not limited to particular set of individuals. It can affect any group. Common biases are based on6

- Beauty

- Educational background

- Gender

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion

- Sexual orientation

- Socioeconomic background

Unconscious biases are more difficult to identify given that people rarely verbalize them, but they still play crucial roles in affecting behavior and judgment. Bias is a large umbrella term that can further be broken down into subgroups and sub-definitions. Table 1 lists some common categories of unconscious or implicit bias. The SIDEBAR discusses recency bias, a type of bias that can have significant influence on providers’ and patients’ healthcare decisions.

Table 1. Major Biases Present in Everyday Life6

| Affinity bias | Unconscious preference for people with whom you share qualities or interests |

| Ageism | Negative feelings towards others based on their age |

| Attribution bias | Related to how you infer the reasons that others act as they do and misunderstand motivations; individuals may attribute their own accomplishments to skill, but assign no fault to their failures; they may be less generous in their thinking when examining others’ behaviors |

| Beauty bias | Belief that attractive people are more successful, competent, and qualified than unattractive people; physical appearance is used to judge competency |

| Confirmation bias | Searching for information that backs the opinion an individual holds and rejecting information that contradicts that opinion |

| Conformity bias | Others’ views influence an individual’s views; this concept is related to peer pressure and acceptance seeking |

SIDEBAR: RECENCY BIAS7,8

Recency bias affects cognitive decision-making by favoring recent events over historic events to estimate future events. Recency bias is also defined as the tendency to base thinking on what comes easily to mind based on recent events.

For example, an employer is conducting employee evaluations and greets an employee who consistently meets performance goals and expectations. However, the employer chooses to deny the employee a promotion based on a recent mistake. Despite consistent success, a recent error influenced the employer’s decision.

In healthcare settings, some examples of recency bias include

- Rejecting older evidence that disproves new (mis)information

- Emphasizing recent information and failing to consider the entire evidence set

- Seeking new information rather than older, more voluminous, and more consistent facts

ETIOLOGY OF BIAS

Science offers some explanation as to how and why biases form in the human mind. The amygdala and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) are most involved in forming bias.9 The amygdala, a small structure located in the temporal lobe of the brain, is responsible for receiving direct information from all the body’s sensory organs.3 It is the part of the brain that generates responses to stimuli, whether that be arousal, attention, or fear.3 The amygdala controls the body’s fight-or-flight response, which is activated in situations that are frightening like walking down a dark alleyway, hearing unfamiliar sounds, or seeing unfamiliar people.3,10

Several neuroimaging studies have shown that activity in the amygdala heightens when people view pictures that trigger biases. For instance, when people see facial images of those from a different ethnic background than that of their own, the amygdala is activated more so than seeing people who look similar to them.3,10

The PFC processes cues and is involved with contingency-based learning, decision-making, and evaluation.3 Essentially, the PFC communicates with the amygdala to signal that visual or auditory cues may not be a danger at all; it effectively regulates or “calms” immediate amygdala activation based on situational surroundings.9,10 The PFC functions to help the brain adjust to fit the environment’s social norms.

Influences of Bias

Social attitudes and expectations that reinforce stereotypes and microaggressions change the way the brain processes behavior. That said, implicit bias is not intrinsic (or hard-wired), meaning although it may exist in the unconscious parts of the brain, it can be “un-wired.”10 Experiments involving children who had diverse friend groups show less reactive amygdala activation, meaning their brains did not automatically associate negative reactions based on skin color.9

What does this have to do with bias? It suggests that bias is not inherently present in children from birth and develops in adolescence.9 The social, physical, and economic environment in which people are raised affects brain development and ultimately alters individual implicit biases.

Identity, Individuality, and Intersectionality

People use their social identity to compartmentalize themselves into specific groups or categories. In 1974, sociologist Henri Tajfel first proposed the social identity theory that suggested social identity derives from the “knowledge of membership” in a group (or groups), and that membership in those groups creates individual significance and value.11 Social identity defines how individuals characterize their own traits. Common identities include things like12

- Disability

- Ethnicity

- Gender or sex

- Nationality

- Political party

- Race

- Religion

- Economic status

Personal identities are adjectives used to describe oneself, like smart, tall, or funny.12

Social identity is dynamic in that it can develop in various ways.10 For example, society classifies people born in the early 1980s to mid-1990s as being part of the millennial generation. Although membership requires nothing other than birth at a specific time, others group millennials into a category (their generation) that has over time acquired certain characteristics typical of group members. Individuals can also develop identity through conscious choices, like choosing to go into a healthcare profession or going to school to be a writer.10 People are not usually limited to one identity, but rather possess multiple social identities that work to influence a person’s experiences in life.12 For example, a White man fits into categorical groups of (1) White person and (2) male sex, yet his life experience may differ depending on if he is born into higher socioeconomic class, identifies as heterosexual, or has a disability.

Society’s cultural norms shape identities.13 As attitudes towards cultures (or groups) change over time, societal standards change as well. Certain identities may have more value and importance than others because society emphasizes those differences. Identities may also shift importance based on the context in which a person lives. A White American living in North America might think about national identity only infrequently. However, if that person takes a job in China, national identity might suddenly feel like a significant part of individual identity, because it will likely impact how others see the person and how the person interprets experiences.12

Social identity overlaps strongly with intersectionality, or the multifaceted interplay of social identities, systems of power, and oppression of certain groups.13 As mentioned above, social identities exist in various combinations that make individuals unique. Intersectionality allows us to see how different identities may affect one another, and how that in turn relates back to concepts of bias, discrimination, and stereotypes.13

Bias within groups can affect intersectionality. For example, studies show that people of color who also identify as part of a sexuality minority experience internalized stigma related to gender and/or sexual orientation within their racial groups; these people experience what is called intersectional minority stress.14 Individuals experiencing discrimination in both racial and gender or sexuality identities are more vulnerable to poor health outcomes given the increased bias and discrimination they face.14

A public health researcher from the University of Michigan introduced the “weathering” hypothesis, which suggests that Blacks experience health deterioration as a result of chronic social and economic stressors or political marginalization.15 Some studies have explored and validated this hypothesis. A recent study found that the COVID-19 mortality rate was 2.1 times higher for Black Americans than that of White Americans.16 The researchers indicate that weathering from chronic and toxic stress magnified COVID-19’s effects in people of color. People of color are more likely to suffer job loss as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak, which in turn affects health insurance coverage and thus contributes to poorer health outcomes. Regardless, even those who possess employment and health insurance are more likely to receive inferior care due to the implicit biases present in healthcare. This study emphasizes the concept of “weathering” in a way that is relevant in our world today.16

PAUSE AND PONDER: How might implicit biases in your workplace affect patient care and outcomes?

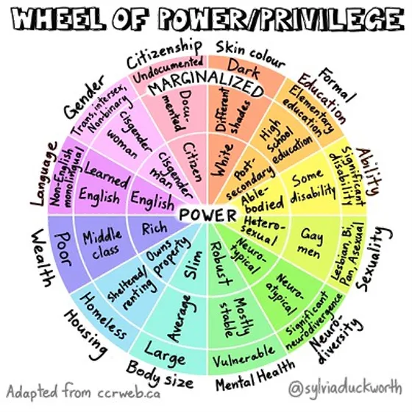

Bias and social identity are entwined. Social identities stem from a person belonging to a group, whether that be an “in-group” or “out-group.” Figure 1 provides examples of the groups, such as middle class or documented citizens. A person can belong to more than one group. Society tends to label certain groups as more valuable than others, which leads to re-enforcement of certain biases. People tend to conform to societal standards, and placing oneself into these groups creates the foundation for bias, stereotypes, and prejudice to occur. It is still important to recognize that while our personal and social identities place us into groups with shared attributes, we are still unique individuals.

SOURCE: Adapted from James R Vanderwoerd ("Web of Oppression"), and Sylvia Duckworth ("Wheel of Power/Privilege")

Institutional Bias

“Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

– Lord Acton, British Historian

All people have unconscious or conscious biases. Ultimately, biases result from social identities’ influence on the brain and our environment. But what happens when a collection of individuals with a shared bias comes together? Biases can become discrimination. While prejudice is the pre-conceived notion about someone based on bias, discrimination is conscious, intentionally disparate treatment.17

Institutional bias, known also as structural bias, ties many issues that arise from discrimination together. Institutional bias—the established laws, customs and practices that methodically reflect and produce group-based inequities in any society—involves policies and practices that are discriminatory beyond that of the individual level.18 Even in an ideal situation wherein individuals do not possess a certain bias or prejudice towards a group of people, discrimination may still occur because the institutions in which they are involved may have biased practices in place.18

Nearly every type of social institution exhibits some form of bias against groups of people. Examples of institutions include18

- Education

- Environmental management

- Healthcare

- Law/Criminal justice

- Military

- Politics

- Politics

- Retail and housing market

- Workforce

Some people allege that individual and institutional bias may not co-exist, but that belief is a bit contradictory. Since the civil rights movement, individual expression of stereotypes and prejudice against Black people in the United States has declined. However, racial discrimination is still widespread and may be as prevalent as it was before the civil right movement in some areas. In 2007, the legal system incarcerated Black people at a rate four times higher than White people in the U.S.18 Although other factors may contribute to this disparity, institutional racism is still prevalent regardless of individuals’ attitudes or bias towards Black people.18

Power and legitimacy also influence institutional biases.18 Groups in power are more likely to control institutional bias since they are most likely to control the institutions and create policy.18 Legitimacy is a word used to describe the perception that a policy that is detrimental to the oppressed group is fair or somehow justified.18

For example, the housing market enables implicit associations between minorities and the risk they present to the value of the neighborhood in which they live or seek to live. As a result, the perception influences certain housing and lending practices for minority applicants.19 Another example is more nuanced. Adults younger than 21 cannot purchase or drink alcohol in the United States; one may argue that this is a form of bias against this age group. However, given the shared societal attitude that teens and young adults should not drink alcohol due to its potential to cause impairment, few people fight against this bias.18

While some biases are widely accepted, others are clearly not. For example, some immigrants don’t qualify for high level positions within companies. Members of immigrant groups are more likely to take low-level, undesirable positions. As a result, they tend not to stay at that company for long, increasing turnover and decreasing ambition within their fields.18 A similar predicament is the standardized college admission tests; depending on their exam score, students may not qualify for admission to certain schools, perpetuating the idea that they are not smart enough to be admitted.18 Standardized tests fail to take into account students’ different backgrounds; some students benefit from simply being in a higher socioeconomic status with resources available to ensure success.

IMPLICATIONS OF BIAS

Negative attitudes have the potential to affect decision making and health outcomes across various healthcare settings. In 2021, the three largest motivations for hate crimes in the U.S. were race, sexual orientation, and religion.20 Maternal mortality rates in the U.S. by race are disproportionate. Black women die during childbirth nearly three times more often than White or Hispanic women.21 These discrepancies are due to institutional biases and existing racism toward Black women in healthcare. The Centers for Disease Prevention and Control adds that implicit bias prevents people of color from having fair opportunities for economic, physical, and emotional health.22 As part of the healthcare workforce, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should be able to identify how implicit biases can adversely impact relationships with patients and customers.

PAUSE AND PONDER: Which interventions described in this CE might help you and your coworkers

have frank discussion about bias and discrimination?

Recent research shows people have self-reported experiences of discrimination in healthcare. These instances frequently occur in the following groups of people23:

- LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer)

- Low socioeconomic status

- Older adults

- Overweight or obese

- Poor health

- Racial/ethnic minorities

- Uninsured

- Women

Patterns of bias and discrimination towards marginalized groups becomes evident. As a result, these individuals can feel perceived discrimination, which is anticipation of unfair treatment they may receive due to their characteristics.23 These groups are more likely to have high stress and mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, and substance abuse.23 Table 2 lists examples of studies that highlight implicit biases related to healthcare.

Table 2. Studies that Highlight Implicit Biases Related to Healthcare24-28

| A study (N = 142) of emergency response situations showed that White bystanders were slower to provide help to Black victims than the speed at which White bystanders helped White victims. White participants helped 88% of White victims compared to 58% of Black victims. “Help Time” was ~120 sec for Black victims compared to ~40 sec for White victims. |

| A review (N = 7070) found Black and Latino patients are less likely to receive medication, especially opioids, to alleviate acute pain in the emergency department than White patients (OR 0.60 [95%-CI], 0.43-0.83). |

| Asian Americans (N = 521) reported feeling like their doctors do not involve them in shared decision making, do not listen to their concerns, and spend less time with them. They were also less likely to receive counseling on mental health or lifestyle issues compared to White patients (N = 3205) in the survey. |

| An analysis found doctors perceived Black patients (N = 618) to be less educated, less likable, less intelligent, and nonadherent to medical advice and medication therapy. Physicians were less likely to agree that Black patients vs. White patients are `the kind of person they could be friends with’ (34% of White vs. 27% of Black patients). |

| A survey (N = 316) showed transgender or gender nonconforming people worry about discrimination when they use pharmacy services; 41.6% reported discrimination associated with such services, and 52.5% reported pharmacists as having very little or no competency in providing gender-affirming care. |

Gender-Diverse Care and Ageism

An emerging topic is gender-diverse care. The Human Rights Campaign Foundation and the American Pharmacist Association (APhA) released a joint pharmacy resource guide for gender diverse care. The guide includes key terms, inclusive communication, staff training and other essential points of patient centered care for gender diverse patients.29 It is accessible for free at https://www.thehrcfoundation.org/professional-resources/transgender-pharmacy-guide

Nicole Avant, PharmD, BCACP, founder, owner, and consultant at Avant Consulting Group, presented key studies on implicit bias during a session at the 2022 National Community Pharmacy Association Annual Convention. They include30

- Black women are more likely to die after being diagnosed with breast cancer.

- Patients of color (POC) receive fewer cardiovascular interventions and fewer renal transplants than White patients.

- POC who have diabetes are more likely to undergo leg amputation.

Poor provider-based interactions negatively impact the quality of care and the desire to seek medical help. This fosters mistrust of healthcare and healthcare workers, like pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. Poor interactions can significantly delay treatment-seeking, which worsens health complications by creating avoidable increases in emergency healthcare use and increasing health disparities. The SIDEBAR provides an example of poor care.

SIDEBAR: A Health Professional’s Observation31

Joanne Whitney is a retired pharmacy professor who has shared her experiences when interacting with healthcare providers.

- She went to the emergency room for a urinary tract infection (UTI) and severe pain. She asked for hydromorphone (Dilaudid) since it had helped her before, but a young physician told her that they don’t prescribe opioids to “those who seek them.”

- Her pain continued for eight hours. She states, “When older people come in like that, they don’t get the same level of commitment to do something to rectify the situation. It’s like ‘Oh, here’s an old person with pain. Well, that happens a lot to older people.’”

- She also told the physician the prescribed antibiotic was incorrect for her UTI, but the provider disregarded her concern despite her pharmacy background.

The prejudice in this case is the notion that older people are unpleasant and difficult to treat. Discrimination occurs when healthcare providers do not manage older adults’ needs appropriately or treat them less favorably than younger patients.

Her experience emphasizes ageism in healthcare settings. More than half a million Americans aged 65 and up encountered ageism during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ageism can be explicit in some healthcare settings. In 2021, an advocacy group for older adults filed a lawsuit in Idaho over the state’s crisis guidelines for hospitals that were overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients. The protocol stated staff should triage and treat younger patients before older adults because “they have more years left” to live.32

Other examples of ageism prevalent in healthcare today include

- Assuming older patients who talk slowly are cognitively compromised

- Rushing patients, not listening to their concerns

- Only speaking to the patient’s family member

- Ignoring or minimizing pain complaints

Racism in Pharmacies

A 2021 U.S. Qualtrics Survey found that nearly 20% of people perceived racial discrimination in community pharmacy settings.23 Of those people, one-third of them felt they had to be particularly careful about their appearance to receive “good service” and avoid harassment.23 On average, people visit doctors and specialists a handful of times but can visit their community pharmacies up to 35 times a year. The study showed that perceived discrimination significantly affects healthcare. One third of respondents stated they tried to avoid certain pharmacies, and 17% reported switching pharmacies. Switching pharmacies may seem like an adequate temporary solution, but in actuality fragments medical records, increases the likelihood that pharmacists will miss potential drug interactions, and compounds adherence issues.23

Thus, healthcare providers must be cognizant of their biases and avoid acting on them when interacting with patients in pharmacy settings. Pharmacy workers should strive to be fair and aware of their personal implicit biases. They should also be conscientious and deliberate when interacting with patients. Management must ensure adequate training is in place for pharmacists and technicians to create a welcoming, inclusive atmosphere. If it is not, pharmacy employees should suggest it is needed.

Becoming conscious about implicit biases should begin during the education of future pharmacists. Six PharmD programs surveyed students (N = 357) using the Harvard Race Implication Test.33 The test determines implicit associations by measuring the time it takes a person to connect two concepts, i.e. (Black/White to good/bad). The survey found that pharmacy students exhibited preference for White patients and moderately negative implicit and explicit bias towards Black patients.33 Although many pharmacy schools have already incorporated the concepts of cultural competence, increasing awareness of how implicit biases negatively affect patient interactions should be a focus area.

Bias Affecting Decision-Making Processes

Implicit bias has been associated with several downstream effects. Consider “second victim” effect. The term “second victim” describes healthcare professionals and the unanticipated emotional impact they feel after making a medical or clinical error.34 Medical errors are one of the top leading causes of death in the U.S.35 The first victim is the patient who experiences the medical error. The second victim—the person who made the errors—feels distress and personal responsibility after an unexpected adverse patient outcome or error. This directly impacts the healthcare professional’s career and life.34 In many cases, implicit bias is not a factor in second victim effect, but sometimes it is. For example, consider a provider who has an implicit bias towards Black women. The provider fails to intervene aggressively when a patient, a Black woman, is experiencing pain and hemorrhaging due to complications during childbirth. The patient soon becomes unconscious from blood loss. The patient unfortunately dies. The patient’s family files a complaint with the hospital regarding the provider’s lack of standard care during her birthing process. The provider is then afflicted by second-victim effect.

Many second victims suffer from job-related emotional and physical stress, and their additional feelings of powerlessness and insecurity can prompt them to leave the profession.34 Lack of support for coworkers and management contributes to the second victim phenomenon, and coworkers and managers may be less likely to support the second victim if they have biases against that person for some reason.34 The second victim’s self-blaming negative feelings could influence future decision making.

Nearly half of healthcare professionals experience second victim effect at least once in their careers.34 This effect may lead to changes in clinical judgment and inadvertently affect patient care. It is important to recognize when it occurs. To combat second victim phenomenon’s negative effects, mindfulness-based interventions have shown efficacy in reducing stress and burnout.34 Also, psychological first aid fosters resilience in healthcare professionals by establishing formal support teams within health institutions.36 This includes education about normal responses to traumatic events, active listening skills, understanding the importance of nutrition and rest, and clarifying when to seek help.36

Interprofessional Bias

Interprofessional collaboration is an important part of managing and delivering quality patient care. Biases about other professions can create conflict within the team, which has negative consequences for communication, decision-making, and trust.37 Implicit biases influence a person’s actions unconsciously and can intrude in various cultural and structural settings. For example, individuals may have preferences for certain specialties or simply certain people over others. Their implicit biases can influence decisions, like who rounds on an inpatient hospital team. The traditional hierarchy of physicians as team “leaders” can create tension within a group that must work with (as equals), but not for (as subordinates), that physician.37

Research shows that biases adversely affect the quality of healthcare delivered to patients. A systematic review on implicit biases in interprofessional collaboration found that biases between professions were predominately negative.37 The review mentioned the concept of internalization, which describes how people internalize biases towards their profession towards their own self and behaviors.37 For example, physicians mostly saw themselves as leaders while nurses consistently perceived themselves as powerless and lacking authority. As such, physicians exhibit behaviors such as authoritatively shutting down communication in case conferences, whereas non-physician professionals tended to be silent, less engaged, or chose to skip team meetings. Bias internalization influenced which professions voiced their opinions and inhibited the team’s overall growth.37 Consequently, these healthcare teams developed feelings of disrespect and mistrust, which impedes patient care. Another study found that when team members perceived they were not consulted about a decision, they exhibited defensive posturing and frustration in meetings.38

Imposter Syndrome

Imposter syndrome is defined as self-doubt about intellect, skills or accomplishments among high achieving individuals.39 Imposter syndrome and disorders such as depression and anxiety are often comorbid.39 Many healthcare professionals strive for perfection, but those with imposter syndrome tend to associate their success with random chance as opposed to their own intelligence.39 Imposter syndrome tends to be more common in marginalized groups (e.g., minority races) in high pressure settings due to underrepresentation in the field; poor representation and pressure exacerbate imposter syndrome.39 It may also be a result of lifelong bias and discrimination, which can affect professionals in their clinical roles as well.

Interestingly, a study of pharmacy residents (N = 720) found higher Clance Imposter Scale scores correlated with the number of hours worked per week and prior mental health treatment, factors associated with high stakes learning environments.40 This study validates other studies done with various medical professionals and demonstrates the connection between highly focused academic and healthcare areas and the increased likelihood of imposter syndrome.40

Imposter syndrome, like the second victim effect, can affect clinical judgement in healthcare professions. It may promote certain biases when they normally would not be due to those feelings of inadequacy, and thus mistakes occur.

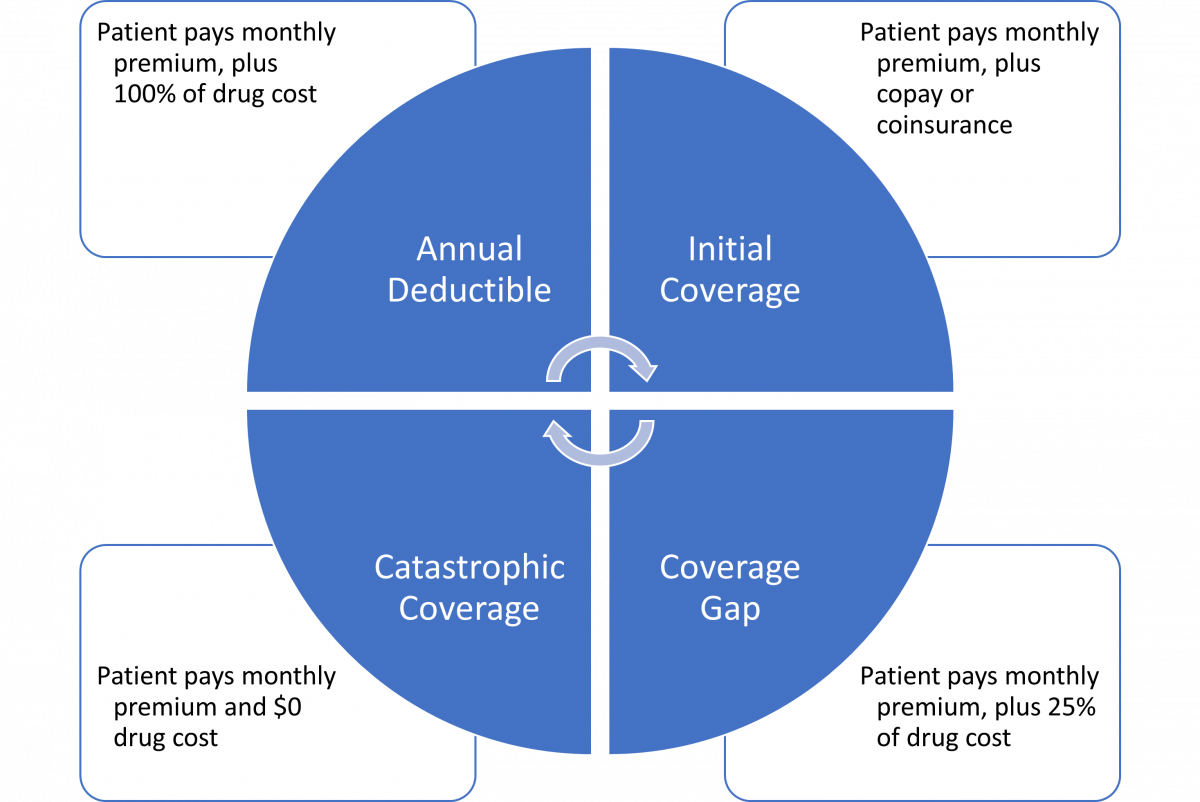

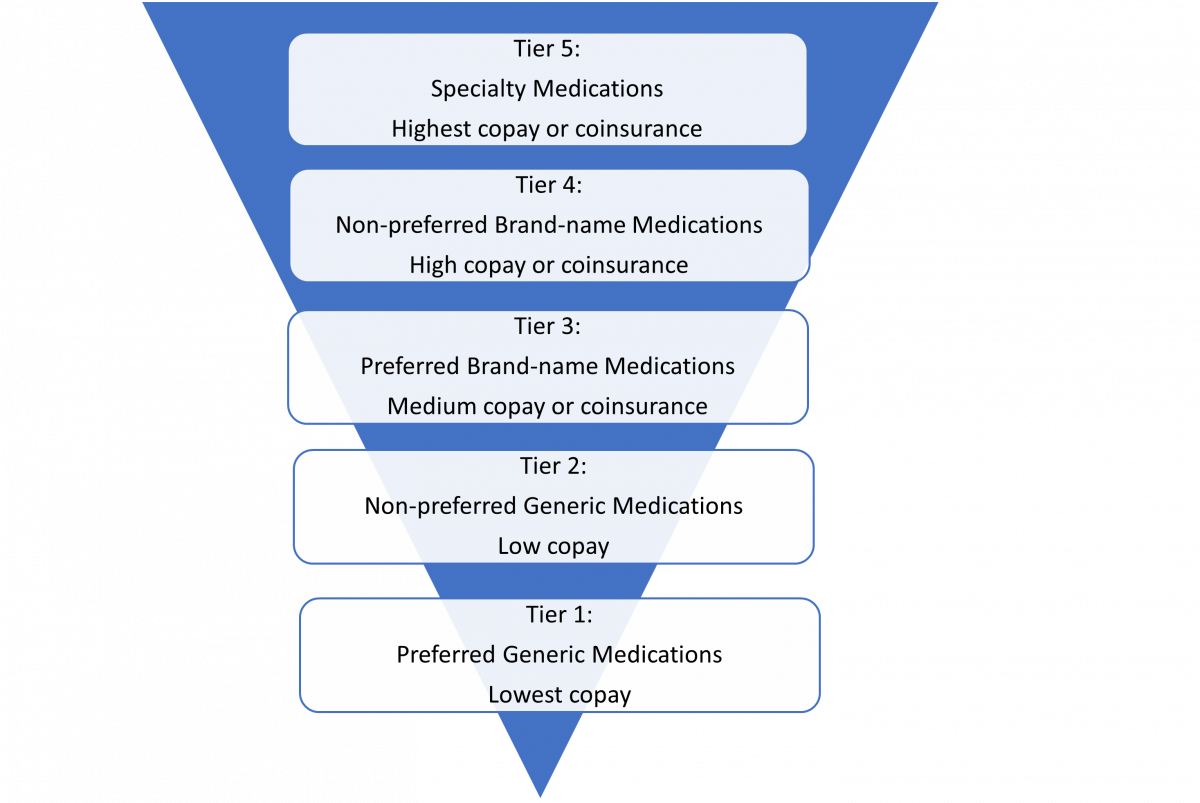

Bias in the Pharmacy

Pharmacists hold crucial positions in healthcare, especially since they engage with diverse groups of patients regardless of the setting in which they work. Pharmacists can stimulate broader efforts to address health disparities, especially as their scope of practice widens.41 Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the social and structural conditions in which people are born, live, and work.42 Figure 2 shows the key SDOH.

Source: Healthy People 2030, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved July 28, 2023, from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

A 2016 review of pharmacy literature highlighted issues stemming from SDOH affecting pharmacies. These factors are known to influence health outcomes, and pharmacy workers need to be aware when SDH may affect the population they serve. The study showed the following knowledge gaps among pharmacists41:

- Mental illness

- Substance/drug abuse with prescription and illicit drugs

- Those at risk for HIV/AIDS or hepatitis C infection

Although pharmacists provide care to groups that suffer from effects of SDH, they may not understand entirely or have access to information that could expose SDH. More education on cultural competency is needed within pharmacy.41

Bias can influence the pharmacy workforce. Perhaps one of the most relevant examples of bias in pharmacy workers concerns opioid use disorder (OUD). The U.S. has battled the opioid crisis for more than two decades.43 Those who suffer with OUD are often stigmatized. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians frequently interact with patients who are diagnosed with such disorders. The lack of knowledge and understanding surrounding OUD underscores biases that exist towards people with OUD.

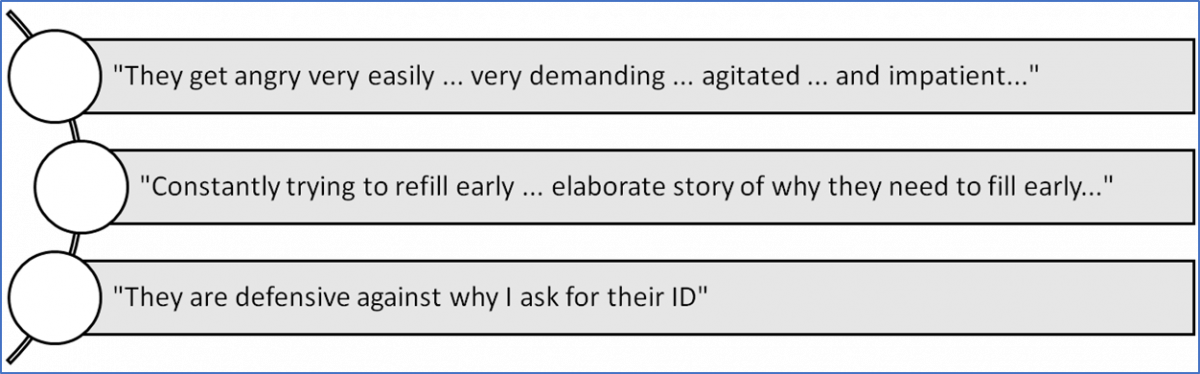

A small study that examined pharmacy technicians’ attitudes (N = 46) using focus groups found that participants had negative perceptions of patients using opioids. Pharmacy technicians reported “ever-present” negative feelings (meaning they persisted over time) toward patients with OUD, even if they did not know opioid’s indication for a particular person.43 The researchers asked pharmacy technicians to recount their experiences with patients who recieved opioids. Figure 3 highlights their perceptions.43

Figure 3. Comments from Pharmacy Staff about Patients with OUD43

A multitude of reasons may explain why participants felt this way. Their experiences may be tied to aggressive encounters between healthcare professionals and patients who use opioids and negative media portrayals of opioid use.43 The study went into further detail on early refills, a situation where patients want to fill a prescription when their fill histories indicate it’s too early. Most technicians stated they tried to be compassionate and non-judgmental in these situations to overcome the stigmas associated with opioid prescriptions.43

The discussion further explained that the negative perception of patients who take opioids compromises quality of care because it is difficult to reverse formed opinions. The National Institute on Drug Abuse stresses the importance of accurate, complete medication histories and reporting to prescription drug monitoring programs to create healthier patient-provider relationships in the pharmacy.43

Another study focused on pharmacy personnel responses to expedited partner therapy (EPT) in the management of sexually transmitted infections. EPT effectively prevents chlamydia and gonorrhea infections for partners of patients already infected.44 Providers can give patients diagnosed with chlamydia or gonorrhea prescriptions for the partner without having to name the partner. EPT is protected by law in 41 states and supported by numerous organizations including44

- American Academy of Pediatrics

- American Academy of Family Physicians

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Society of Adolescent Health and Medicine

The study (N = 50) found pharmacists refused to fill 58% of EPT prescriptions, and suburban pharmacists were more likely to refuse than city pharmacists.44 Refusal was more likely if the pharmacists were older than the patient and if patients were White. Pharmacists most commonly cited lack of name on the prescription as the reason for refusal, even if the law does not require a partner name. This indicates a general lack of knowledge about EPT among study participants, which may have contributed to their decisions.44

A literature review on weight management programs found implicit and explicit weight bias exists within the pharmacy profession. Weight management programs can vary, and pharmacies offer some in conjunction with prescription medications and nonpharmacologic lifestyle interventions.45 The review found stigmatizing language in the screening processes for weight management programs. It is unclear to what extent weight biased communication exists between pharmacists to patients.45 The stigma that surrounds obesity affects other related health problems, like diabetes or cardiovascular concerns, and can weaken the pharmacist-patient relationship.45

ADDRESSING BIAS

Implicit biases are present in all people, but the importance lies not in the existence of bias, but how to overcome it. Several strategies address biases, the most important being education in pharmacy school curriculums. Many studies use the IAT to measure implicit bias. The test is free to the public and can be found here: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/

Learners should note that this is not just one test, but a series of different tests.

The IAT measures the time it takes for the individual to match concepts in categories to descriptive words, like race, skin tone, and weight to good, bad, or other stereotypical language.46,47 An individual’s underlying beliefs drive responses time, thus measuring the strength of the association between concepts (a person, image, etc.) and evaluations (good, bad). Researchers recommend incorporating the IAT in curriculums prior to before direct patient exposure.46

Other interventions that may be helpful in pharmacy education and other pharmacy settings include44

- Practicing mindfulness (directing active, open attention to the present to examine one’s thoughts and feelings without judging them). Mindfulness reduces the likelihood of activating implicit biases and enhances the ability to control biases in patient care situations.

- Self-awareness/self-reflection training: After completing the IAT, individuals can reflect on identified biases.

- Activating goals: Healthcare workers can identify goals that promote fairness and equality for patients and coworkers.

- Stereotype replacement: Individuals who collect information that is opposite of cultural stereotypes can replace stereotypical thoughts with non-biased thoughts.

- Case studies observing implicit bias: Analyzing case studies where implicit bias was involved helps people recognize how to approach situations differently.

- Individuating: This action challenges people to see others for their individual traits as opposing to grouping them by their stereotypical components.

- Perspective-taking: This “walk a mile in their shoes” activity asks individuals to assume the perspective of a stigmatized or marginalized member to build empathy.

The University of Utah Pharmacy Residency program implemented an implicit bias awareness and action seminar with four training modules and a pre- and post-test survey. After training, pharmacy residents indicated higher comfort and confidence addressing personal biases and were better able to identify biases of others.47 While not accessible to the public, this shows that implementing training programs makes a difference in future of pharmacy delivered care.

Conclusion

Implicit biases have overall negative effects on patient care, which is detrimental to patients and those that harbor the implicit biases. Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who are aware of and take steps to address their implicit biases will improve the way they treat patients and each other as colleagues.

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

Exploring Implicit Bias and Its Impact in Pharmacy

POST-TEST Pharmacists

Learning Objectives

After completing the continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

• DEFINE different types of bias and how they are formed

• RECOGNIZE what bias may look like in the pharmacy setting

• IDENTIFY how bias can impact patient care

• APPLY methods to address and mitigate bias in the workplace

1. You are a 52-year-old clinical pharmacist who works with an interprofessional team. The doctor is a 33-year-old resident who has just started working at the hospital. He does not ask for your input, yet you have caught several prescribing errors he made. He also ignores your questions. He has openly stated that he thinks pharmacists “don’t know what they are talking about.” What potential bias may be occurring?

a. Age bias

b. Interprofessional bias

c. Confirmation bias

2. Which strategy could potentially help mitigate implicit biases in pharmacy education or clinical settings?

a. Behavioral therapy

b. Anonymous reporting

c. Self-awareness training

3. Which of the following statements best describes an explicit bias?

a. “Women who have children are not serious about professional careers.”

b. “Pharmacists and doctors have more clinical education than nurses do.”

c. “Patients of color receive fewer primary care interventions than White patients.”

4. Which of the following statements is CORRECT regarding the etiology of bias?

a. The amygdala processes cues and “calms” the PFC to adjust to social norms.

b. Neuroimaging studies do not associate amygdala activity and bias.

c. Bias triggers amygdala activity and affects decision-making processes.

5. How does bias negatively impact marginalized pharmacy customers?

a. Patients struggle to fill medications due to shortages.

b. Patients feel they have to be careful of their appearance.

c. There is not really bias towards patients in pharmacy.

6. A new pharmacy resident was paged to attend a stroke code and unfortunately, the patient died because the resident did not know which medication to give at the moment. This was the fifth unsuccessful stroke code this month, and the resident is troubled. He starts drinking more after his work shift to help cope with the feelings of loss. After several months, he is diagnosed with depression. He is often late to work and his supervisors counsel him several times. What is the resident experiencing?

a. The resident is experiencing second victim syndrome.

b. The resident does not like his job or his bosses.

c. The resident is experiencing imposter syndrome.

7. Which choice correctly defines social identity and intersectionality?

a. Social identity is the relationship between intersectionality and systems of power; intersectionality is the process of being placed into a group

b. Social identity and intersectionality are different terms for the same concept, and researcher tend to use the two interchangeably in studies and review articles

c. Social identity relates to being placed in an “out-group” or “in-group”; intersectionality is the relationship between social identities and power systems

8. How does the Implicit Association Test (IAT) work?

a. It measures how fast White responders help Black victims in emergencies.

b. It measures the strength of participants’ personal beliefs towards minorities.

c. It measures how quickly participants associate concepts to categories.

9. Which of the following statements about bias internalization is TRUE?

a. Internalized bias has no impact on teamwork, and affects only the individual.

b. Internalized bias has no impact on individual, and affects only the whole team.

c. A bias toward a group of people can be internalized and applied to one’s self.

10. A recently pharmacy graduated has been hired to work on your team. You notice that the new pharmacist tends to hand off minority patients who need a language interpreter to other coworkers. You bring this up to your supervisor, who asks for your suggestions. Which statement is the best intervention?

a. The supervisor should call a team meeting and directly address the new pharmacist in front of everyone to hold that person accountable.

b. The team should review case studies similar to the minority patients so the new pharmacist can feel more comfortable working on those cases.

c. The manager should fire the new pharmacist because recent graduates should know how to manage all cases, even when an interpreter is needed.

Pharmacy Technician Post Test (for viewing only)

Pharmacy technician post-test

After completing the continuing education activity, the pharmacy technician will be able to:

• define different types of bias and how they are formed

• recognize what bias may look like in the pharmacy setting

• identify how bias can impact patient care

• illustrate understanding of strategies that mitigate bias

1. A female technician has worked in a retail pharmacy for several years. She notices the pharmacist always asks for the male technicians to help her put away the order, despite her being there much longer than they have. When she asks the pharmacist why she doesn’t ask for her help, the pharmacist says, “Oh, I just thought it was too heavy for you.” Which statement best describes this case?

a. Male technicians are better and more efficient workers than female technicians.

b. The pharmacist does not like working with the female technician.

c. The pharmacist’s thinking that females are not as strong as males is gender bias.

2. Which statement correctly identifies the differences between explicit and implicit bias?

a. Implicit biases are unconscious; explicit biases are conscious.

b. Explicit biases are harsher than implicit biases.

c. Implicit biases do not have anything to do with explicit biases.

3. You work in a retail pharmacy and a patient drops off a new prescription for Suboxone. When the patient comes to pick up the medication, you notice he is defensive when you ask to see an ID for verification purposes. What is one possible reason for their reaction?

a. The patient feels you may be judging him for his prescription.

b. The patient is offended and thinks you are calling him old.

c. The patient does not have his ID with him at the moment.

4. A female inpatient pharmacy technician is working with a male pharmacy resident to perform a medication history review. The tech notices the resident tends to rush through the interactions with older patients and will only speak to the family if they are present in the room. The tech has overheard this resident state he thinks the nurses should take medication histories since residents have “more important jobs than nurses.” With regard to the pharmacy resident, which bias may negatively affect patient care the most?

a. Affinity bias

b. Interprofessional bias

c. Age bias

5. Which statement is a microaggression?

a. A doctor says “Black women are at higher risks for maternal mortality.”

b. A faculty member says, “Most Black students are poor or illiterate”

c. A patient says, “I want to speak with to the doctor I saw last month.”

6. An APRN is concerned with a medication dose and asks to speak to the pharmacist. When finished with the call, the pharmacist turns to you and says, “APRNs are so incompetent. They never know how to send things over the right way.” Which statement describes the bias the pharmacist is displaying?

a. The pharmacist shows interprofessional bias towards the APRN.

b. The pharmacist in this example is not showing any explicit bias.

c. The pharmacist shows unprofessional bias towards the APRN.

7. How can practicing mindfulness help reduce biases in healthcare settings?

a. It reduces the likelihood of activating implicit biases and enhances the ability to control biases in patient care.

b. It helps healthcare providers take on the perspective of stigmatized or marginalized group members to build empathy.

c. It is designed to let healthcare providers develop goals that promote fairness and equality among coworkers.

8. Over the course of your career in pharmacy, you come to realize that your initial belief that patients who are prescribed multiple refills of opioids are abusing them is wrong. What is this an example of?

a. Stereotype

b. Interprofessional Bias

c. Ageism

9. Which statement describes how the brain plays a role in forming bias?

a. The amygdala and PFC both process social cues that turn to bias most of the time.

b. The PFC is triggered by sensory information while the amygdala processes cues.

c. The amygdala is triggered by sensory information while the PFC processes cues.

10. Which is an example of how implicit biases can influence institutional bias?

a. A Black male is unable to cast his vote at the ballots because he forgot his ID at home

b. A young Hispanic female is denied pain medication because the doctor thinks she’s exaggerating her pain

c. A disabled male athlete does not qualify for a sporting event because he places last in the competition

References

Full List of References

References

1. Barlow R. Bu research: A Riddle reveals depth of gender bias: BU Today. Boston University. Published January 16, 2014. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.bu.edu/articles/2014/bu-research-riddle-reveals-the-depth-of-gender-bias/

2. Vela MB, Erondu AI, Smith NA, Peek ME, Woodruff JN, Chin MH. Eliminating Explicit and Implicit Biases in Health Care: Evidence and Research Needs. Annu Rev Public Health. 2022;43:477-501. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-052620-103528

3. Amodio DM. The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(10):670-682. doi:10.1038/nrn3800

4. Ashcraft D, Treadwell T. Chapter VII: The Social Psychology of Online Collaborative Learning: The Good, the Bad, and the Awkward. In Orvis K, Lassiter A, eds. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning: Best Practices and Principles for Instructors. IGI Global; 2008:11-15. doi.org/10.4018/978-1-59904-753-9.ch007

5. Sparks SD. Fighting Subtle Bias: Classroom Biases Hinder Students’ Learning. Published October 27, 2015; Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/classroom-biases-hinder-students-learning/2015/10

6. Murphy N. Types of Bias. CPD Online College. Published November 10, 2021. Updated May 27, 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://cpdonline.co.uk/knowledge-base/safeguarding/types-of-bias/

7. Phillips-Wren G, Power DJ, Mora M. Cognitive bias, decision styles, and risk attitudes in decision making and DSS. J Decision Syst. 2019;28(2):63-66. doi: 10.1080/12460125.2019.1646509

8. Salim A, Johnson WE. How Bias and Perception Impact Complicance.https://assets.hcca-info.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Resources/Conference_Handouts/Compliance_Institute/2019/304_Bias%20and%20Perception.pdf

9. Weichselbaum C, Banks K. Racism on the Brain. Fron Young Minds. 2021;9:1-8. doi:10.3389/frym.2021.608843

10. Agarwal P. What Neuroimaging Can Tell Us about Our Unconscious Biases. Published April 12, 2020. Accessed April 12, 2023 https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/what-neuroimaging-can-tell-us-about-our-unconscious-biases/

11. Everett JAC, Faber NS, Crockett M. Preferences and beliefs in ingroup favoritism. Fron Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:1-21. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00015

12. Leading Effectively Staff. Understand Social Identity to Lead in a Changing World. Published February 7, 2023. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.ccl.org/articles/leading-effectively-articles/understand-social-identity-to-lead-in-a-changing-world/

13. Kearney, DB. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) for Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA). Module 4.2 Positionality and Intersectionality. eCampus Ontario; 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/universaldesign/

14. Sarno EL, Swann G, Newcomb ME, Whitton SW. Intersectional minority stress and identity conflict among sexual and gender minority people of color assigned female at birth. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2021;27(3):408-417. doi:10.1037/cdp0000412

15. Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. "Weathering" and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):826-833. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749

16. Johnson-Agbakwu, C.E., Ali, N.S., Oxford, C.M. et al. Racism, COVID-19, and Health Inequity in the USA: a Call to Action. J. Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9: 52–58.

17. López L, Betancourt JR. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. In: Loscalzo J, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J. eds. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, 21e. McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3095§ionid=263343935

18. Henry, P. Institutional Bias. In: Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, Esses VM, eds. Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. Sage; 2010:426-440

19. Olinger J, Capatosto K, McKay MA, et al. Challenging Race as Risk: How Implicit Bias Undermines Housing Opportunity in America. Ohio State University; 2017:1-85. Accessed July 20, 2023. https://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/challenging-race-risk-implicit-bias-housing

20. FBI. Number of Victims of Hate Crime in The United States in 2021, by Motivation. Statista. Published March 13, 2023, Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/737648/number-of-hate-crime-victims-in-the-us-by-motivation/

21. Hoyert DL. Maternal mortality rates in the United States, 2020. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2022. doi.org/10.15620/cdc:113967

22. Working Together to Reduce Black Maternal Mortality. CDC. Updated April 3, 2023. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/features/maternal-mortality/index.htm

23. Baffoe JO, Moczygemba LR, Brown CM. Perceived discrimination in the community pharmacy: A cross-sectional, national survey of adults. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2022;63(2):518-528. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2022.10.016

24. Kunstman JW, Plant EA. Racing to help: Racial bias in high emergency helping situations. J Pers Socl Psych. 2008;95(6)1499-1510. doi.org/10.1037/a0012822

25. Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(9):1770-1777. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.06.014

26. Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Phillips RS. Asian Americans' reports of their health care experiences. Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):111-119. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30143.x

27. van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians' perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813-828. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x

28. Lewis NJW, Batra P, Misiolek BA, Rockafellow S, Tupper C. Transgender/gender nonconforming adults' worries and coping actions related to discrimination: Relevance to pharmacist care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(8):512-520. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxz023

29. Human Rights Campaign Foundation, APhA. Providing Inclusive Care and Services for the Transgender and Gender Diverse Community: A Pharmacy Resource Guide. Published March 2021. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.thehrcfoundation.org/professional-resources/transgender-pharmacy-guide#overview

30. Hippensteele A. Expert: 'we all hold implicit biases' that may contradict explicit beliefs, impact patient health. Pharmacy Times. Published October 2, 2022. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/expert-we-all-hold-implicit-biases-that-may-contradict-explicit-beliefs-impact-patient-health

31. Graham J. 'they treat me like I'm old and stupid': Seniors decry health providers' age bias. KFF Health News. Published October 20, 2021. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://kffhealthnews.org/news/article/ageism-health-care-seniors-decry-bias-inappropriate-treatment/

32. Boone R. Civil rights complaint targets Idaho Health Care Rationing. AP News. Published September 24, 2021. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-business-discrimination-race-and-ethnicity-idaho-4a152d4f4f809bfb6588b9025c400d6b

33. Santee J, Barnes K, Borja-Hart N, et al. Correlation Between Pharmacy Students' Implicit Bias Scores, Explicit Bias Scores, and Responses to Clinical Cases. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;86(1):8587. doi:10.5688/ajpe858

34. Miller CS, Scott SD, Beck M. Second victims and mindfulness: A systematic review. J Pat Saf Risk Manag. 2019;24(3):108-117. doi:10.1177/2516043519838176

35. Coughlan B, Powell D, Higgins MF. The Second Victim: a Review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;213:11-16. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.04.002

36. Everly GS. Psychological first aid to support healthcare professionals. J Pat Saf Risk Manag. 2020;25(4):159-162. doi:10.1177/2516043520944637

37. Sukhera J, Bertram K, Hendrikx S, et al. Exploring implicit influences on interprofessional collaboration: a scoping review. J Interprof Care. 2022;36(5):716-724. doi:10.1080/13561820.2021.1979946

38. Simpson A. The impact of team processes on psychiatric case management. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60(4):409-418 doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04402.x

39. Huecker MR, Shreffler J, McKeny PT, Davis D. Imposter Phenomenon. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; September 9, 2022.

40. Sullivan JB, Ryba NL. Prevalence of impostor phenomenon and assessment of well-being in pharmacy residents. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(9):690-696. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxaa041

41. Wenger LM, Rosenthal M, Sharpe JP, Waite N. Confronting inequities: A scoping review of the literature on pharmacist practice and health-related disparities. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(2):175-217. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.05.011

42. CDC. Social Determinants of Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/about/sdoh/index.html

43. Cernasev A, Desselle S, Hohmeier KC, Canedo J, Tran B, Wheeler J. Pharmacy Technicians, Stigma, and Compassion Fatigue: Front-Line Perspectives of Pharmacy and the US Opioid Epidemic. Int J Envir Res Pub Health. 2021; 18(12):6231. doi:10.3390/ijerph18126231

44. Borchardt LN, Pickett ML, Tan KT, Visotcky AM, Drendel AL. Expedited Partner Therapy: Pharmacist Refusal of Legal Prescriptions. Sex Transm Dis. 2018;45(5):350-353. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000751

45. Murphy AL, Gardner DM. A scoping review of weight bias by community pharmacists towards people with obesity and mental illness. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2016;149(4):226-235. doi:10.1177/1715163516651242

46. Prasad-Reddy L, Fina P, Kerner D, Daisy-Bell B. The Impact of Implicit Biases in Pharmacy Education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;86(1):8518. doi:10.5688/ajpe8518

47. Terry K, Nickman NA, Mullin S, Ghule P, Tyler LS. Implementation of implicit bias awareness and action training in a pharmacy residency program. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2022;79(21):1929-1937. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxac199

The University of Connecticut, School of Pharmacy, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Thirty and one half contact hours (3.05 CEU’s) will be awarded to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who view the presentations, participate in the activities and complete the assignments and evaluations, and deliver their final submission. Statements of credit for ACPE UAN 0009-0000-23-057-B04-P/T will be automatically sent to CPE Monitor and can be printed from your CPE Monitor Profile. A Certificate of Achievement will be sent to those who complete all activities, evaluations and submit a complete Verification of Participation Form.

The University of Connecticut, School of Pharmacy, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Thirty and one half contact hours (3.05 CEU’s) will be awarded to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians who view the presentations, participate in the activities and complete the assignments and evaluations, and deliver their final submission. Statements of credit for ACPE UAN 0009-0000-23-057-B04-P/T will be automatically sent to CPE Monitor and can be printed from your CPE Monitor Profile. A Certificate of Achievement will be sent to those who complete all activities, evaluations and submit a complete Verification of Participation Form.