INTRODUCTION

Bullying is a popular topic these days. Hardly a day goes by without a story in the media about school bullies, social media bullies, celebrity bullies, political bullies, and even chef bullies. In addition, lawsuits have found people and organizations liable for suicides when they bullied the victim (called the target) or failed to address bullying.1 And many times, serial killers or individuals who conduct mass shootings are later identified as having been bullied. Clearly, the United States (U.S.) has a bullying problem. Does healthcare and, on a smaller scale, pharmacy, have a bullying problem?

This continuing education activity discusses bullying in the workplace because healthcare and on a smaller scale, pharmacy, do have bullying problems and students sometimes experience bullying as they are introduced to the profession on rotations or in residencies. Unlike harassment, bullying isn’t illegal in the U.S., but it has serious repercussions to individuals and organizations. Recognizing and addressing workplace bullying is essential to foster healthy and supportive work environments in healthcare settings, ultimately benefiting both staff and patients. Although the authors drafted this activity to address the bullying that students sometimes experience in experiential rotations, during extensive peer review, reviewers indicated this topic is of interest to all pharmacy personnel, not just preceptors.

Mock, Taunt, Intimidate

Workplace bullying is a widespread issue that affects various industries, including pharmacies and other healthcare settings. Most of the data in healthcare comes from studies of physicians’ interactions with other disciplines, and the American Medical Association (AMA) recognizes the problem. AMA defines workplace bullying as “repeated, emotionally or physically abusive, disrespectful, disruptive, inappropriate, insulting, intimidating or threatening behavior targeted at a specific individual.”2 Bullying’s purpose is to control, embarrass, undermine, threaten, or cause harm toward an individual. Various factors at the individual, organizational, and health system level can contribute to creation of an unprofessional workplace climate or culture.2

Workplace bullying is important to address because it can impact patient care, resulting in preventable mistakes. In a 2021 survey, roughly 35% of healthcare providers had concerns about medication orders but chose to assume correctness to avoid engaging with specific providers. One pharmacist was shamed by a colleague after seeking an independent double check for a vancomycin order with incorrect timing. Multiple errors like this occur annually because of the culture of shaming.3 Some data about how bullying affects the medication prescribing and administration process demonstrates this subject’s importance.

Every few years, the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) surveys healthcare professionals about disrespectful behaviors and intimidation in the workplace.4,5 ISMP conducted its most recent survey in September 2021.3 Among the 1,047 respondents, 26% worked in the pharmacy, suggesting that bullying is a problem in pharmacies since a disproportionate number of pharmacy employees responded compared to more populous health care providers like physicians and nurses. A full 37% of respondents were pharmacists and 6% were pharmacy technicians.3

Disrespectful behaviors were clearly linked to medication concerns3:

- 40% of respondents said past disrespectful behaviors had altered the way they handled order clarifications or questions about medication orders.

- Roughly half of respondents said that they had relied on colleagues to interpret or validate an order rather than contact the prescriber in the past year; the reason was to avoid contact with the disrespectful prescriber.

- 11% of respondents indicated they avoided talking to a prescriber to interpret or validate an order’s safety more than ten times in the previous year.

- 7% said that they had been pressured to accept an order, dispense a product, or administer a drug despite safety

- Slightly more than one-third reported having concerns about a medication order but assumed it was correct rather than interact with a specific prescriber; roughly the same number of respondents said that a prescriber’s stellar clinical reputation often made them reluctant to question or clarify orders even if they had concerns.

TYPES OF WORKPLACE BULLYING IN HEALTHCARE

In the limited research that addresses workplace bullying in pharmacies and other health care settings, researchers frequently bemoan the fact that, the AMA’s definition aside, we have no consensus definition of bullying. It would be ideal if we could provide a concise definition of bullying or a checklist that would help managers, supervisors, coworkers, and preceptors ascertain when bullying is occurring. In fact, bullying occurs in many different forms.

Verbal Bullying

Verbal bullying encompasses various forms of harmful language and communication. Examples of verbal bullying include mocking, name-calling, teasing, or intimidating someone to belittle or demean them. Insults and derogatory comments can degrade a person's self-esteem, creating a hostile working environment. Fans of the television show NCIS may recall that the section supervisor, Leroy Jethro Gibbs, always dubbed the newest hire “Probie,” which appears to have been short for probationary employee. People watching this show who are familiar with human resources regulations often shuddered when Gibbs did this, as it could be perceived as a form of bullying. Especially in government organization where the rules are very clear, such behavior would be dangerous. In pharmacies, calling people by unwelcome nicknames could be perceived as bullying.

Public humiliation is another form of verbal bullying that aims to embarrass the person who is being bullied in front of others. Trainees commonly report persistent attempts from their preceptors or trainers to humiliate them in front of colleagues. According to a study, “The abuse of students is ingrained in medical education and has shown little amelioration despite numerous publications and righteous declarations by the academic community over the past decade.”6

PAUSE AND PONDER: A preceptor asked a student a question in front of the rounding team. The student, who was unable to answer, blushed and stuttered. The preceptor said, “What school of pharmacy did you go to again? I need to call them and ask them what they're teaching because you clearly should have known the answer to this question.” The student reddened even more, and the preceptor said, “Oh! So, you're a blusher are you?” Was this teasing, was this misplaced humor, or was it bullying?

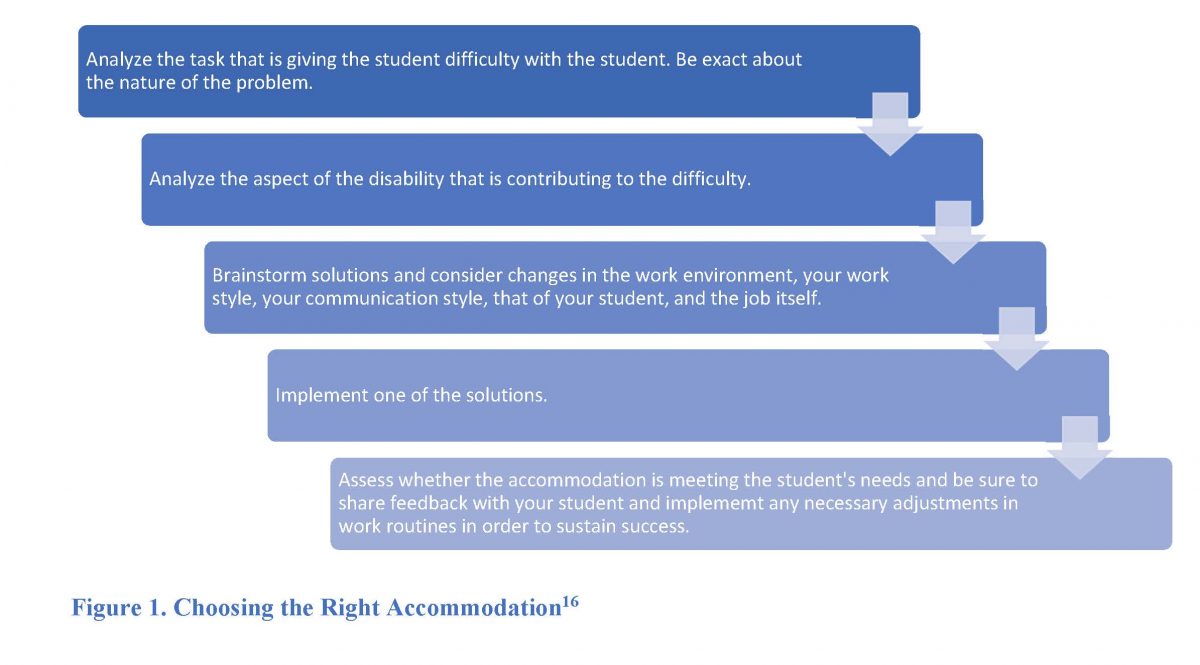

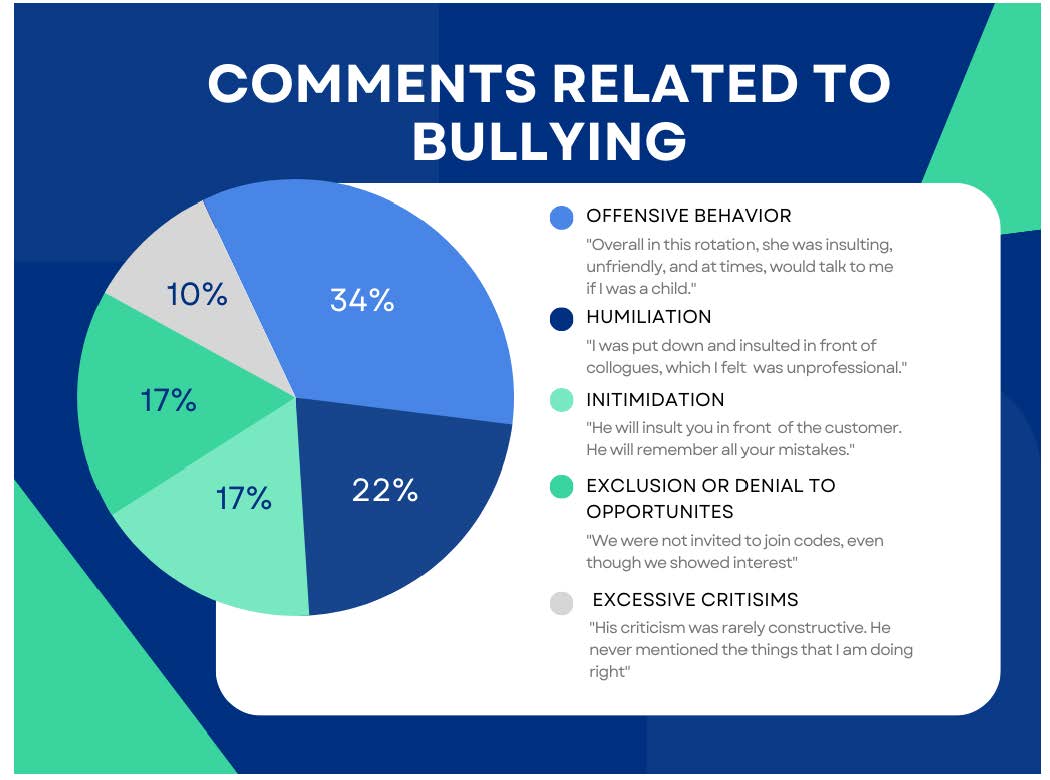

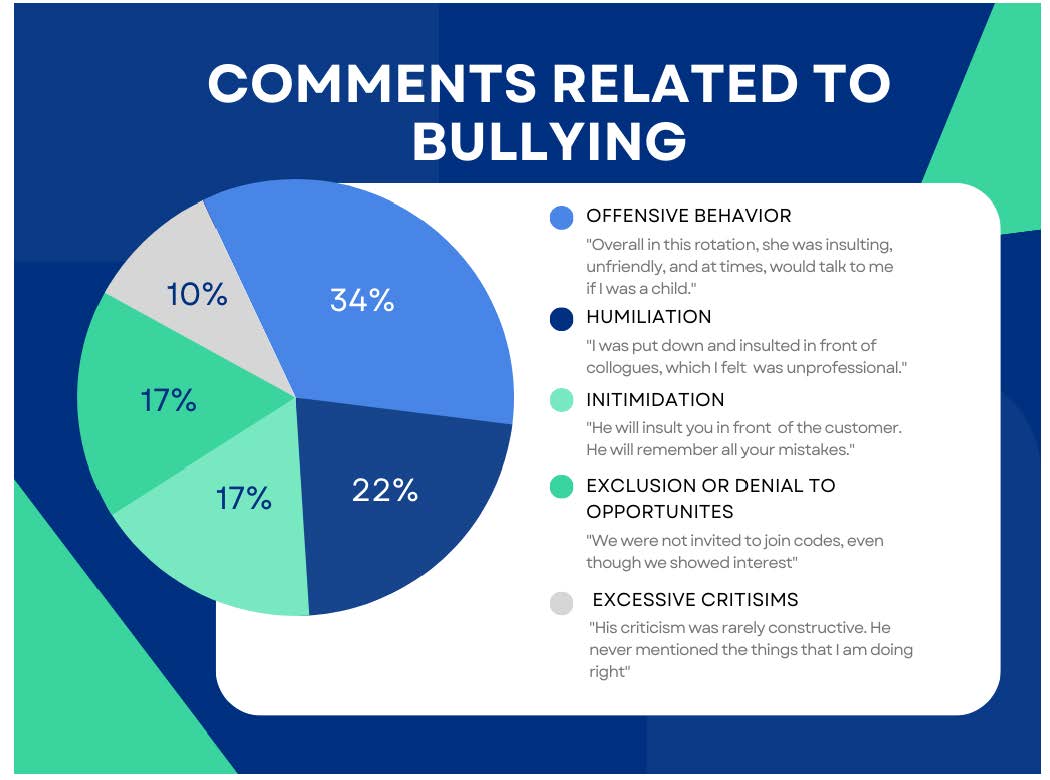

The term bullying does not appear in the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards. Researchers reviewed the professional literature and American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) survey data collected from student evaluations of preceptors (N = 2087); students provided low evaluations for preceptors in at least one area in 119 evaluations.6 When the researchers scanned the comments for words or phrases closely associated with bullying, they found respondents reported 34 instances indicating bullying. Figure 1 shows the distribution of comments and includes examples of troublesome comments.6

Figure 1. Comments Related to Bullying from Pharmacy Survey Data6

This data came from one college of pharmacy, but the researchers compared their data to that of a national study.6 It was similar. Although the rates of bullying seemed low, the researchers believed that bullying is seriously underreported in pharmacy. Some reasons may include the small number of pharmacists compared to physicians and nurses, the use of assessment tools that are not intended to identify bullying (asking the wrong questions), and students’ reluctance to complain because it may be perceived as unprofessional. Students may also be afraid that reporting bullying may affect their grades. The researchers recommend ACPE place more emphasis on bullying and develop of a consensus definition.6

Intimidation and threats instill fear and anxiety, leaving the target feeling vulnerable and powerless. Intimidating behaviors in the healthcare workplace are far from isolated incidents. A survey conducted with more than 2,000 healthcare providers revealed that subtle, yet effective forms of intimidation were more common than explicit forms.4 Respondents reported encountering behaviors such as condescending language, impatience with questions, and reluctance to answer or return calls. Physicians and prescribers were identified as the primary perpetrators of intimidation, exhibiting behaviors such as condescension, reluctance to answer questions, and verbal abuse more frequently than other healthcare providers.4

Additionally, destructive criticism is another unjustified way in which someone can wear down the target emotionally and psychologically. Constructive criticism and destructive criticism differ based on their delivery and the ways in which they impact individuals and their work.7 Constructive criticism uplifts people by providing suggestions and potential solutions while highlighting both positive aspects of someone's work and identifying areas for improvement. Destructive criticism undermines confidence, belittles efforts, and focuses on ridicule, leading to decreased morale and performance. It creates a hostile atmosphere and restrains productivity.7

Constructive feedback begins and ends with positive comments and present information in a supportive way, as this “compliment sandwich” exemplifies:

“Jacob, I appreciate your dedication and commitment to our pharmacy team. However, I've observed a higher number of medication errors when you’re dispensing prescriptions, which is unusual based on your work history. I know how dedicated you are to the team, so if you're facing any challenges that may be impacting your performance, please don't hesitate to reach out to me or any team member. We are here to support you and provide the best patient care possible."

Destructive feedback is replete with negativity:

"Jacob, your work recently in the pharmacy has been extremely disappointing. Why are you making so many mistakes? It's causing a lot of problems for the team, and frankly, I don't have the time or patience to fix everything for you. You really need to step up and improve your performance because it's negatively impacting our overall productivity."

It’s not always possible to use a compliment sandwich when addressing issues in the pharmacy. It is always possible to be kind.

Verbal bullying is usually easy to spot if the bully conducts the browbeating in public. In one pharmacy, a seasoned technician seemed to have a bias against students who were accruing IPPE or APPE hours. She would frequently tell students loudly, “If you can’t work any faster, it would be lovely if you would just get out of the way.” Her colleagues would turn a blind eye, but the section supervisor eventually took action and referred her to employee assistance. However, many bullies are adept at mounting their campaigns of terror when no one is looking. (Remember that the most likely place for bullying is schools is in the most difficult place to supervise: the playground.8)

Non-Verbal Bullying

Non-verbal bullying in healthcare manifests through actions that undermine and harm the target without using explicit words.9 Bullies use exclusion and social isolation to insulate targets from their colleagues, fostering a sense of loneliness and alienation. Undermining and sabotage minimize the target's work and efforts, eliminating a culture of safety.9

PAUSE AND PONDER: A preceptor assigned one pharmacy student to sort and file a large backload of paperwork. She also assigned a technician to explain what needed to be done and how. The technician was frustrated by the student’s questions, but two hours later, the student finished sorting. He asked the technician to check his work before he filed it. The technician riffled through the pile, said, “This is correct,” and then said, “Oops!” and intentionally dropped the entire pile on the floor. Was that bullying?

Ignoring and dismissing ideas invalidates targets’ contributions and suggestions which diminishes their confidence and ability to perform well.10 Additionally, intentionally withholding information deprives targets of essential knowledge needed to perform their assigned tasks effectively.9 Individuals who use “the silent treatment” (refusing to engage in discussion and making no eye contact) are also bullies. Researchers have found that people in positions of power who use the silent treatment also frequently assign unreasonable or unnecessary tasks.11

Finally, bullies may also use noise in subtle ways to intimidate or disturb targets. In one situation, students were assigned to work in an office across from a pharmacist who did not like to precept but did so because he was assigned the task. He kept his door closed most of the time but would slam it hard when coming and going. He’d watch to see if the students reacted.

Physical Bullying

While less common in healthcare, physical bullying involves direct aggression towards the target.12 This can include pushing or shoving, which poses a threat to the target’s safety and well-being. Damaging personal belongings is another form of physical bullying, violating the target's personal space and property. Also forcing physical exertion on the target, such as excessive workloads or tasks beyond their capacity, can cause physical harm and exhaustion.12

Healthcare workers are already at risk for physical violence, and four times more likely to experience violence requiring an absence from work than people employed in other industries.12 According to 2013 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data, 80% of serious violent incidents were a result of interactions with patients. The remaining incidents were attributed to visitors, coworkers, or individuals outside of the healthcare facility with 3% of the incidents from coworkers.12

BLS found one fact of particular note: Employees were significantly less likely to report bullying and other forms of verbal abuse. They cited three contributing reasons: (1) lack of a reporting policy, (2) lack of faith in the reporting system, and (3) fear of retaliation, which is discussed below.12 Although healthcare workers appear to be more likely to be bullied by patients than coworkers, concerns about reporting flaws and retaliation may skew the data.12

SIGNS AND EFFECTS OF BULLYING

Absent a clear definition, healthcare managers and workers may struggle to identify bullying or differentiate it from harassment. Signs may be obvious—as in the example of the technician who tells students to get out of the way—or subtle.

Signs of Workplace Bullying

Recognizing the signs of workplace bullying is crucial for early intervention. Behavioral changes in targets, such as increased irritability, anxiety, or withdrawal, may indicate they are experiencing bullying.13

Effect on Workers and Patients

Workplace bullying has detrimental effects on both healthcare professionals and the quality of patient care.9 The emotional and psychological impact on targets can lead to heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. This affects their well-being and their ability to provide optimal care to patients. Bullying can contribute to higher rates of medication errors, increased infections, and other negative patient outcomes. This is partly due to staff members' fear of speaking up against physicians or prescribers who are bullies.14 Physician Alan Rosenstein, an expert in disruptive behavior, highlights the existence of a "hidden code of silence" that keeps coworkers or colleagues from reporting or appropriately addressing many incidents.14

Rosenstein has collected anecdotes from his work. He doesn’t report any from situations involving pharmacists or technicians, some examples of disparaging remarks/actions may feel somewhat familiar to pharmacy workers who have had unfortunate interactions with prescribers14:

- During a tense operation, a surgeon insulted a male nurse, who had a special needs son, by saying, "You're a [r-word] just like your boy." The nurse filed a written complaint because of the insulting, disrespectful remark.

- At Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, a surgeon proceeded with an operation without washing his hands. Instead of openly addressing the issue, a nurse discreetly offered the surgeon gloves, but he simply discarded them into the trash.

- An OB/GYN patient was experiencing excruciating pain while the doctor sutured without providing sufficient anesthetic. When questioned by a medical student, the doctor made a joke saying that the patient could be given memory-erasing ketamine to forget about the experience.

It is essential for pharmacy owners to recognize the consequences of workplace bullying on their businesses. Table 1 lists negative consequences of unaddressed bullying and provides examples. Preceptors, supervisors, mentors, and organizations must address factors that promote bullying (like power imbalances, addressed below) and provide employees with support to maintain healthy, successful pharmacy settings.

Table 1. Negative Consequent of Unaddressed Bullying15

| Consequences |

Examples |

| Diminished morale |

A seasoned pharmacy technician (whose pronouns = they/them), who has been working diligently for years, consistently faces belittling comments and criticism from the pharmacist. As a result, their overall enthusiasm for their work decreases, affecting their productivity and leading to a sense of resignation or disengagement. The rest of the staff will also feel disengaged and resigned. |

| Strained employee relations |

One pharmacist consistently questions another pharmacist’s decisions and recommendations in front of colleagues and patients leading to tension and hostility between them. This strained relationship might extend beyond work-related matters, making collaboration difficult and creating an uncomfortable atmosphere for other team members. |

| Loss of respect for management |

Employees witness a manager ignoring complaints, failing to provide a safe and supportive environment. The affected employees lose respect for the management team as they perceive the lack of intervention as a sign of management’s incompetence, leading to a diminished view of their leadership abilities. |

| Increased absenteeism/

tarnished reputation |

Over time, employees are subjected to behaviors of bullying and begin to experience high levels of stress and anxiety due to the hostile environment. So, the employees start taking more sick days or even extended leaves of absence to cope with bullying’s emotional toll. The toxic work environment spreads through word of mouth among colleagues, potential hires, and even patients. The pharmacy’s reputation suffers as news of the toxic work environment and unaddressed bullying gets around. |

Ultimately, workplace bullying may reduce everyone’s job satisfaction and productivity resulting from the negative work environment created by workplace bullying.16 Extensive studies have confirmed the association between workplace bullying and perceptions of organizational settings, including job satisfaction and commitment. Job dissatisfaction, which leads to emotional distress, can be regarded as a factor that influences employees’ commitment to their work.16

CAUSES AND RISK FACTORS

To effectively address workplace bullying, preceptors—and all staff—need to understand the underlying causes and risk factors contributing to its occurrence in healthcare settings.

Power Imbalances

Power imbalances can contribute to disruptive behavior in healthcare settings, leading to a range of negative consequences. (Yes, this means the bully might be the boss!8) While some may associate disruptive behavior with overt bullying and intimidation, the broader definition preferred by experts includes any actions that undermines safety culture.14

The issue of power imbalances in pharmacy is a growing concern, as evidenced by a 2015 report from the United Kingdom’s Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service (ACAS).15 Workplace bullying has been on the rise in the U.K., with a staggering 20,000 calls annually reporting bullying incidents to ACAS. Disturbingly, this problem extends to community pharmacies, where staff members face bullying from pharmacy owners, managers, supervisors, and colleagues.15 The level of labor stability also has a significant impact on vulnerability to bullying because lower-status employees often hold the most unstable and temporary jobs. An empirical study (a study that uses observation, measured phenomena, and participant’s experience rather than theory or belief) conducted among university employees in an academic center aimed to demonstrate that flexible working arrangements contribute to the prevalence of bullying.16 One reason for the increase in bullying within organizations is the restructuring processes and higher levels of outsourcing, which have widened the power gap between managers and employees.16

High Stress Levels and Demanding Work Environment

The demanding nature of healthcare work, coupled with high stress levels, can create an environment prone to workplace bullying.16 Healthcare professionals often face intense pressure, long working hours, and challenging situations that may increase tension and exacerbate conflicts. Stress can amplify negative behaviors and create a breeding ground for bullying. Bullying within a stressful environment can lead to burnout and cause talented, compassionate individuals to leave the healthcare profession.17,16

Do pharmacy employees experience stress? In a recent survey, 61.2% of pharmacists reported experiencing significant burnout in their practices.17 This trend is prevalent among hospital pharmacists, with consistent rates across various practice settings and areas. The study reveals that those most affected by burnout were often unmarried, had no children, and worked extended hours, surpassing 40 hours per week. Pharmacists can be impacted by stress and burnout in all practice settings. Thus establishing support systems with family, friends, and coworkers is vital to enhancing morale and alleviating feelings of burnout.17

High Expectations from Society

Healthcare professionals are entrusted with caring for the health and well-being of individuals, and society places high expectations on them. The pressure to meet these expectations, combined with limited resources and time constraints, can contribute to stressful work environments that may foster workplace bullying.18 Most healthcare workers feel like they are held to higher standards than the general public. This feeling is rooted in centuries of traditions and most medical organizations emphasize respect in personal interactions.18

Healthcare workers also believe that the general public’s expectations of them outside the healthcare setting are set too high.12 The demanding and high-stress nature of healthcare work can make it challenging for professionals to enjoy their personal lives. The constant feeling of being at work and the fear that their actions could be scrutinized even during off-hours creates additional stress and anxiety. This work-life imbalance can have a significant impact on well-being and overall quality of life.18

Lack of Policies and Procedures to Address Bullying

The absence of comprehensive policies and procedures specifically targeting workplace bullying in healthcare settings can perpetuate its occurrence.19 Without clear guidelines and protocols in place, both targets and bystanders may feel powerless and unsure of how to address and report bullying. Instances of bullying and verbal abuse are often under-reported for various reasons. As revealed by the 2022 National Pharmacy Workplace Survey by industry experts, the lack of robust policies and procedures to address bullying in the pharmacy profession is a pressing concern.19 The study highlights the absence of a formal mechanism for pharmacists and pharmacy personnel to discuss workplace issues with supervisors and management. This leads to an unwelcoming atmosphere, resulting in heightened stress and eventual burnout. Over 60% of respondents indicated that their employers did not actively seek their opinions, nor did employers respect or value employee input.19 Employers, insurers, lawmakers, and the public must come together to ensure ample resources, address patient safety concerns, and promote the well-being of pharmacy personnel.

One topic also needs more attention: the bullying individual. The SIDEBAR provides information about people who tend to bully others.

SIDEBAR: Some People are Simply Bullies20,8,21,22

Bullies Unveiled: Bullies are individuals who employ intimidation and control tactics to further their own objectives. While they might appear cooperative when their goals align with the team’s or the employer’s, their methods are unfair and dishonest. In the workplace, bullies often target coworkers in lateral or lower responsibility positions, resorting to manipulation and terrorizing behaviors. They may even intimidate superiors, using tactics like threats of resignation during crises.

The Hidden Shame: Some psychologists attribute bullying to ingrained shame, although others cite insecurities, disparate socioeconomic backgrounds, personality traits that make them outliers, and basic insecurities. Some theories indicate that targets of bullying are more likely to become bullies. Contrary to common belief, bullies don't necessarily suffer from low self-esteem. Instead, their behavior can stem from internalized shame. While some individuals who harbor shame may have low self-esteem, those who engage in bullying tend to have high self-esteem, and hubristic (overbearing or presumptuous) pride. Bullies may also be quite clever. Their attacks on others are defense mechanisms to alleviate their own feelings and ignore their real emotions.

Shame's Impact on Coping: Early in life, people develop various responses to shame, which solidify into personality traits by adulthood. These coping mechanisms can be categorized by attacking others, self-attacking, avoidance, and withdrawal. For those who bully, the fear of shame, such as being perceived as inadequate at work, drives them to target others. Bullies exploit others' vulnerabilities—and especially others’ insecurities—and redirect their own shame onto their targets. The bully’s ultimate feeling is power.

Narcissism and Withdrawal: Some bullies ultimately develop narcissistic traits, continually attacking others as a means to cope with deeply rooted shame. Conversely, targets are often sensitive individuals who respond to shame by self-blame. This response might maintain a connection with the bully and perpetuates a victim or target mentality. Withdrawal, another reaction to shame, involves concealing one's emotions and can lead to depression. Prolonged exposure to workplace bullying often triggers this response, proving just as harmful as self-attacking.

Seeking Solutions: Bullying deflects a bully's shame and also provides a sense of power. However, many bullies remain unaware of their own inadequacies. The key to dealing with workplace bullies is solidarity among coworkers. Banding together against a bully offers support, as targets of bullying often face isolation and by confronting the bully's behavior collectively, coworkers can neutralize their power. Banding together does not mean ganging up on the bully. It means using the principles of bystander intervention (discussed below) and firmly calling out bullying when one sees it in a respectful but direct manner. Documenting repeated episodes of bullying is also critical.

Readers should note, however, that when the bully’s target is someone that others tend to dislike or find little sympathy for, the team may not coalesce to support the target. Supervisors, managers, or observers who are leaders need to jump in and remind staff that bullying is unacceptable, and if the target leaves, who knows who will be next. Further, some research indicates that bullies may eventually become targets; backlash is not an ideal solution.

A Path Forward: Ultimately, bullies can change their behavior by developing better coping mechanisms and learning to process their feelings constructively. Recognizing that bullies are driven by a response to shame or other factors, rather than consciously acknowledging it, is essential for devising effective strategies to address this issue. Supervisors and managers should refer employees with bullying tendencies to their employee assistance programs or similar programs.

DIFFERENTIATING WORKPLACE BULLYING, HARASSMENT, AND DYSFUNCTION

To address workplace bullying effectively, healthcare workers and managers must differentiate it from harassment and dysfunction within the healthcare setting.

Key Differences in Behaviors and Intent

While workplace bullying and harassment share similarities, such as the creation of a hostile work environment, they differ in terms of intent and behaviors. Again, bullying is often described as offensive, intimidating, malicious, or insulting behavior intended to undermine, humiliate, denigrate, or injure the recipient, and it may involve individuals or groups.23 It can take various forms, including spreading rumors, excluding someone, giving unachievable tasks, and more.

Harassment, as defined by U.S. employment discrimination laws, involves unwelcome conduct based on various protected characteristics including race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, or genetic information. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA), and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) all prohibit harassment as a form of employment discrimination.24 The difference between bullying and harassment is subtle. For example, calling a coworker or a student a skinny witch is bullying. Calling a coworker or a student a skinny Catholic witch introduces the element of religion. While neither is acceptable, the introduction of religion crosses the line to harassment. While bullying is not necessarily illegal, harassment based on protected characteristics is unlawful.

PAUSE AND PONDER: Consider a technician who announces to all who are on duty that the new student smells terrible. Is that bullying or harassment? If he follows it up with, “It’s because people from his culture cook all that stinky food!” Is that bullying or harassment?

Laws and Regulations against Workplace Harassment

Various laws and regulations protect employees against workplace harassment. Title VII, ADEA, and ADA prohibit harassment on a federal level, while individual states also have laws that require employers to enact anti-harassment policies.24,25 Harassment is illegal and someone—meaning anyone who is harassed or observes harassment—should report it when it creates a work environment that a reasonable person would find intimidating, hostile, or abusive. It is crucial to prevent harassment, and employers should establish clear anti-harassment policies, provide training, and address complaints appropriately.

Supervisors, co-workers, or non-employees may harass others, and the employer may be liable for harassment by supervisors resulting in disciplinary actions.24,25 For non-supervisory harassment, employers can be liable if they knew or should have known about the harassment and failed to take corrective action. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) assesses each case of harassment individually by considering the nature and context of the conduct. Overall, addressing harassment requires proactive measures and a commitment to maintaining a respectful work environment. 24,25

Protection of Whistleblowers

Whistleblowers are protected under OSHA’s Whistleblower Protection Program, which enforces provisions from more than 20 whistleblower statutes safeguarding employees from retaliation for reporting violations.26 Retaliation is strictly prohibited under these laws and encompasses actions such as firing, demoting, denying benefits, intimidation, harassment, and other adverse actions. Retaliative actions may dissuade an employee from raising concerns about potential violations. Subtle actions like exclusion from important meetings or false accusations of poor performance can be considered retaliation. Temporary workers supplied by staffing agencies are also protected from retaliation. OSHA's program not only safeguards whistleblowers reporting violations, but also shows some similarities between retaliation and workplace bullying. Exclusion and intimidation are shared tactics in both retaliation and bullying, mainly differing in the employer's intent.26 Many experts in bullying indicate that given these parallels, employees who are targets of bullying should be protected in the same manner that whistleblowers are safeguarded. This approach would foster a work environment where all individuals can voice concerns and engage in their roles without fear of adverse consequences.

PREVENTION AND INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

Although the U.S. hadn’t yet addressed workplace bullying formally, Australia has.27 Its Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth), allows its Fair Work Commission to hear bullying claims and order any corrective action other than monetary compensation) to stop bullying from continuing. In 2019, the Fair Work Commission heard a claim from a pharmacist. The SIDEBAR summarized the case, which ended in a ruling in favor of the employer but raised many questions. It highlights the complexities of these kinds of cases and the fact that some people have little insight into their behaviors.

SIDEBAR: Who’s Bullying Who?27

A pharmacist alleged the pharmacy’s management was bullying him by scheduling him to work on Saturdays without adequate assistance. The employer had replaced a dispensing technician with an intern pharmacist who he considered incompetent. The pharmacist claimed it created unnecessary stress, doubling his work. He alleged that the pharmacy’s Saturday workload was similar to weekday workloads and required more staff.

The employer demonstrated successfully that its Saturday workflow was significantly lower than weekdays. CCTV footage revealed that the pharmacist spent considerable time on Saturdays looking at his phone rather than working. The employer also indicated the pharmacist engaged in aggressive and intimidating conduct, even reducing the intern to tears on one occasion. His hostile behavior extended to other employees, leading two of them to seek counseling. The employer stated that the pharmacist's inability to work cooperatively with colleagues was the root of the problem, not the intern's competence.

The deciding official ruled no one acted unreasonably towards the pharmacist. He acknowledged the pharmacist's unacceptable behavior that involved mistreating several other employees. Some readers are no doubt reading this and nodding their heads, having seen, been subject to, or accused of bullying rightly or wrongly. Others are thinking, “Why is this guy still employed?”

To combat workplace bullying effectively in healthcare, a multi-faceted approach involving various strategies is necessary.

Policy Development and Enforcement

It is essential to develop policies to combat workplace bullying in all pharmacy settings. Drawing from the AMA's report, pharmacy management can adopt key steps to create an effective anti-bullying policy and cultivate a positive work environment.2 Everyone involved needs to realize that developing a policy takes time, and implementing it requires an endless, consistent effort on the part of managers, supervisors, and staff. People from every level of the organization should have input into the draft and the review process. Putting the issue on the department’s staff meeting agenda will ensure that it doesn’t fall through the cracks.8

First, management must ensure that the administration is fully aware of the impact of unprofessional behavior. The team can create strategies proactively to address and prevent bullying by recognizing the problem. One strategy might be to identify when and where the bullying occurs. Changes to the workflow, the schedule, or the supervision can improve the situations.8

Second, management can arrange to educate the entire pharmacy staff about the harmful consequences of unprofessional or hostile conduct. When employees perceive that their leaders are committed to addressing bullying, they are more likely to report incidents or even intervene when witnessing inappropriate behavior among colleagues. Two types of education can help28:

- Federal law requires certain organizations to provide compliance training on harassment and discrimination. The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission also recommends (but does not require) workplace civility training. Workplace civility training promotes workplace respect and civility. Good training would include workplace norms, appropriate and inappropriate behaviors in the workplace, and possibly interpersonal skills, conflict resolution, and effective supervisory techniques.

- Bystander intervention training, usually associated with sexual harassment in schools, is increasingly recognized as a critical element of efforts to decrease harassment and inappropriate behaviors. Its goal is to refine employees’ sensitivity to harassment or bullying and empower them act. This training would need to identify offensive behaviors, describe employment non-discrimination laws, and explain how bystanders should respond upon witnessing a harassment incident.

These crucial management steps and well-structured anti-bullying policies can foster a respectful and supportive workplace, promoting the well-being of all employees and enhancing overall patient care.

Promoting a Supportive and Respectful Workplace Culture

Healthy working relationships are crucial to promoting a supportive and respectful workplace culture in the pharmacy. The most important characteristics that build good working relationships include29

- mutual respect

- open communication

- empathy

- building rapport with every member of the team.

Table 2 defines these terms. Practicing mindfulness (awareness of one’s feelings and the impact they have on themselves and others) can further improve relationships by reducing stress and anxiety, increasing emotional intelligence, and improving communication. It is essential to address inappropriate behavior promptly to prevent escalation, with support and guidance available to deal with bullying or harassment.

Table 2. Key Characteristics of Healthy Working Relationships29

| Characteristic |

Definition |

| Mutual respect |

The foundation of a healthy workplace where all members of the pharmacy team are valued and their views are acknowledged. |

| Open communication |

Free expression of ideas without fear of criticism, fostering trust and understanding |

| Empathy |

Compassionate comprehension of others’ states when connecting with colleagues and patients so effective communication, negotiation, problem-solving, and assertiveness to enhance collaboration and conflict resolution is possible. |

| Building rapport |

Fostering a positive dynamic with every team member to enhance workplace happiness |

PAUSE AND PONDER: Janine supervises three employees, Mary, Alice, and Siobhan. Mary and Alice are very close and tend to gossip. They dislike Siobhan, speak badly of her to others, and often fail to provide the information Siobhan needs to complete her work. They criticize her work cruelly in the weekly staff meeting. Siobhan’s name is pronounced shi-VON, but Mary and Alice consistently mispronounce it and misspell it. What should Janine do, and how can she support Siobhan?

Encouraging Reporting and Providing Confidential Channels

Managers, supervisors, and preceptors should encourage healthcare workers to report incidents of bullying without fear of retaliation.14 They should establish confidential reporting channels to protect the identities of those who come forward.14

When addressing bullying within the pharmacy setting, it is essential to establish a comprehensive reporting system that includes confidential channels for employees to voice their concerns.14 Vanderbilt University uses a slowly escalating corrective approach, where trained professionals engage in open discussions with alleged offenders, fostering an environment of respect and mutual understanding. Second offenses are met with warnings, followed by formal letters outlining the issues and potential interventions such as mental and physical screening (in case a health condition is causing symptoms of anger, frustration, and lack of patience). Repeat offenders may face the consequence of losing staff privileges.14

Apart from corrective measures, effective strategies can also focus on providing help and support to offenders, such as anger management classes, counseling, or assistance with medical or addiction issues.14 Creating a reporting system that ensures confidentiality empowers pharmacy staff to come forward with their concerns, enabling prompt intervention.

CONCLUSION

Workplace bullying in healthcare is a pressing issue that requires attention and action. It negatively impacts healthcare professionals’ well-being and compromises patient care. It is crucial to define and emphasize workplace bullying so we can shed light on the significance of addressing this problem. To reiterate

- Understanding the types, signs, and effects of workplace bullying allows us to recognize its presence and take appropriate measures.

- Identifying the causes and risk factors helps us understand the underlying factors contributing to its persistence in healthcare settings.

- Differentiating workplace bullying from harassment and dysfunction clarifies the specific behaviors and intent involved, leading to more effective interventions.

- Upholding laws and ethical obligations, along with whistleblower protection, ensures legal and ethical accountability.

- Creating prevention and intervention strategies, such as developing policy and promoting a supportive culture, provide a framework for addressing workplace bullying.

- Reporting incidences through mechanisms and confidential channels empower individuals to seek help and create a safer environment.

In conclusion, by recognizing, preventing, and intervening in cases of workplace bullying, healthcare organizations can create a better work environment that supports their employees and promotes optimal patient outcomes.