About this Course

UConn has developed web-based continuing pharmacy education activities to enhance the practice of pharmacists and assist pharmacists in making sound clinical decisions to affect the outcome of anticoagulation therapy for the patients they serve. There are a total of 17.25 hours of CPE credit available. Successful completion of these 17.25 hours (13 activities) or equivalent training will prepare the pharmacist for the Anticoagulation Traineeship, which described below in the Additional Information Box.

The activities below are available separately for $17/hr or as a bundle price of $199 for all 13 activities (17.25 hours). These are the pre-requisites for the anticoagulation traineeship. Any pharmacist who wishes to increase their knowledge of anticoagulation may take any of the programs below.

When you are ready to submit quiz answers, go to the Blue "Take Test/Evaluation" Button.

Target Audience

Pharmacists who are interested in making sound clinical decisions to affect the outcome of anticoagulation therapy for the patients they serve.

This activity is NOT accredited for technicians.

Pharmacist Learning Objectives

At the completion of this activity, the participant will be able to:

|

|

|

|

Release Date

Released: 07/15/2025

Expires: 07/15/2028

Course Fee

$34

ACPE UAN

ACPE #0009-0000-25-046-H01-P

Session Code

25AC46-MXT39

Accreditation Hours

2.0 hour of CE

Bundle Options

If desired, “bundle” pricing can be obtained by registering for the activities in groups. It consists of thirteen anticoagulation activities in our online selection.

You may register for individual topics at $17/CE Credit Hour, or for the Entire Anticoagulation Pre-requisite Series.

Pharmacist General Registration for 13 Anticoagulation Pre-requisite activities-(17.25 hours of CE) $199.00

In order to attend the 2-day Anticoagulation Traineeship, you must complete all of the Pre-requisite Series or the equivalent.

Additional Information

Anticoagulation Traineeship at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT

The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy and The UConn Health Center Outpatient Anticoagulation Clinic have developed 2-day practice-based ACPE certificate continuing education activity for registered pharmacists and nurses who are interested in the clinical management of patients on anticoagulant therapy and/or who are looking to expand their practice to involve patient management of outpatient anticoagulation therapy. This traineeship will provide you with both the clinical and administrative aspects of a pharmacist-managed outpatient anticoagulation clinic. The activity features ample time to individualize your learning experience. A “Certificate of Completion” will be awarded upon successful completion of the traineeship.

Accreditation Statement

The University of Connecticut, School of Pharmacy, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE #0009-0000-22-046-H01-P will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program.

Grant Funding

There is no grant funding for this activity.

Requirements for Successful Completion

To receive CE Credit go to Blue Button labeled "take Test/Evaluation" at the top of the page.

Type in your NABP ID, DOB and the session code for the activity. You were sent the session code in your confirmation email.

Faculty

Heather Surerus-Lopez, PharmD, BCACP, CACP

Certified Clinical Pharmacist, Ambulatory Services

St. Joseph Medical Center Pharmacy

CommonSpirit Health

Tacoma, WA

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Dr. Surerus-Lopez has no relationships with any ineligible companies and therefore has nothing to disclose.

Disclaimer

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Program Content

ABSTRACT

Many different guidelines and clinical studies address how to manage anticoagulation around the time of surgeries or procedures. This module’s goal is to help learners pull dry information together and apply it to real-world anticoagulation situations. It discusses terminology, renal function assessment, recent guideline changes, and how to stratify a patient’s periprocedural risk of thrombosis and bleeding. In addition, the module covers anticoagulation during the periprocedural period, potential interactions with over-the-counter products, and how to communicate the plan with patients and caregivers. It includes practice pearls from an experienced certified anticoagulation provider. Finally, it concludes with a sample case to show learners how to use this information in typical situations in direct patient care.

INTRODUCTION

Appropriate perioperative anticoagulation management is essential for patient safety. Guidelines can be valuable tools for identifying a potential course of action when tailoring perioperative plans for individual patients who take anticoagulants. However, significant gray areas remain. Clinicians must consider individual patient characteristics before finalizing any plan. This module familiarizes learners with the most recent guidelines and demonstrates how to optimize perioperative anticoagulation care for patients.

Many guidelines about anticoagulation are available. Good clinical practice requires occasional surveillance for changes in the current landscape. Select organizations that periodically release guidelines include the American Society of Hematology (ASH), the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA), and the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST). This module primarily uses the 2022 Perioperative CHEST Guideline. Please note, guidelines sometimes refer to medications that are used internationally, but this module only discusses medications available in the United States. Additionally, each institution’s protocol or clinician’s opinion may vary from the views presented here.

TERMINOLOGY

- "Bridging" refers to using a shorter half-life anticoagulant to act as a "bridge" between pre-procedure and post-procedure maintenance anticoagulation. This action minimizes patients' exposure to subtherapeutic anticoagulation while their maintenance anticoagulation is held for a procedure. Most commonly, this refers to using low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) while warfarin is held.

- Practice Pearl: Patients or providers sometimes incorrectly refer to simply holding an anticoagulant as "bridging."

- “DOAC” refers to the direct oral anticoagulants (the Factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban [Xarelto], apixaban [Eliquis], edoxaban [Savaysa], and the Factor IIa inhibitor dabigatran [Pradaxa]). The old term "NOAC" has fallen out of favor as it implies a negative connotation.

- “Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitor” refers to the antiplatelet agents eptifibatide (Integrilin) and tirofiban (Aggrastat).

- “Low-molecular weight heparin” refers to enoxaparin (Lovenox) and dalteparin (Fragmin).

- “P2Y12 inhibitor” refers to the antiplatelet drugs clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient), ticagrelor (Brilinta), and cangrelor (Kengreal).

- The terms “surgery” and “procedure” are sometimes used interchangeably.

ESTIMATING RENAL FUNCTION

Some anticoagulants are renally cleared, so clinicians must be prepared to make dose adjustments for renal impairment. Directly measuring glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not practical, so formulas that estimate renal function guide treatment decisions. Commonly used formulas use serum creatinine (SCr), height, age, and some form of body weight (in kg) to estimate renal function (discussed in more detail later). Calculators for these equations are available online.

Renal function formulas assume stable renal function and the results are just estimates, so the anticoagulation team must consider the whole patient when making dosing adjustments. Note that neither the CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation (2021) nor the Cockcroft-Gault formula have been validated for use in children, pregnancy, or patients with low creatinine values.

The most recent Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Guidelines recommend using the CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation (2021) to estimate renal function. This formula takes body habitus (common variations in the shape of the human body, which in turn determines the position of internal viscera) and gender into account and is now widely used.1

CKD-EPI Creatinine Equation (2021)

eGFRCr = 142 x min (SCr/k,1)α x max (SCr/k,1)-1.200 x 0.9938Age x 1.012 [if female]

Female: k = 0.7, α = -0.241; Male: k=0.9, α= -0.302

“min” =minimum of SCr/k or 1; “max” = the maximum of SCr/k or 1

Then convert the result to a non-indexed eGFR using BSA as follows:

BSA (m2) = 0.007184 x (weight in kg) 0.425 x (height in cm) 0.725

Non-indexed eGFR = indexed eGFR x BSA /1.73 (result expressed as mL/min/1.73 m2)

This formula estimates kidney function more accurately than others, is widely regarded as the current standard of care, and reference laboratories use it. However, the pharmacokinetic studies that lead to United States (U.S.) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval often use the historical Cockcroft-Gault (CG) formula instead. Therefore, FDA-approved prescribing information often bases renal dosing adjustments on CG creatinine clearance (CrCl).2

Cockcroft-Gault Formula (1976)

CrCl = [((140–age) x (weight in kg))/ (72 x SCr)] x 0.85 (for females)

The Cockcroft-Gault formula was developed from data collected from white adult males and often yields inaccurate results when applied to the general population. The formula’s developers suggestion for an 85% correction for female gender was not derived from clinical data. They acknowledged its limitations. Its flaws have been extensively discussed.1,3,4 Common patient characteristics that may yield inaccurate results include:

- Actual body weight (ABW) either below or more than 30% above, ideal body weight (IBW)

- Edema

- Frailty

- Height under 60"

- Hydration status

- Low muscle mass

Special Populations

Unfortunately, choosing an appropriate measure of body weight to use in CG is not always as simple as having the patient step on the scale. Table 1 describes how clinicians use different representations of body weights in different circumstances.

| Table 1. Choosing a Measure of Body Weight for Use in Cockcroft-Gault | |

| Representation of Body Weight | Patient Population |

| Actual body weight (ABW) | Underweight, and all patients using rivaroxaban |

| Ideal body weight (IBW) | Between IBW and 30% overweight |

| Adjusted body weight (AdjBW0.4) | More than 30% overweight |

Adjusting Weight for Obesity

The literature suggests adjusting body weight for obesity (body weight greater than 30% over IBW). The adjusted body weight (AdjBW) is calculated using the following formula, and the result is used in the CG formula.5

IBW (male) = 50 + (2.3 x (height minus 60 inches))

IBW (female) = 45.5 + (2.3 x (height minus 60 inches))

AdjBW0.4 = IBW + 0.4 (ABW - IBW)

Practice Pearl: Note that the rivaroxaban prescribing information specifically calls for using Actual Body Weight when calculating CrCl.6

Adjusting Weight for Amputations

Currently, no validated method is available to estimate renal function in patients who are amputees. One possible method is to estimate the IBW before the amputation, subtracting an approximation of what that limb might have weighed (see Table 2), then using the AdjBW in the formula. Alternatively, clinicians can use an online calculator such as https://clincalc.com/kinetics/ebwl.aspx.7

| Table 2. Estimating Body Weight Lost from Amputations8 | ||

| Body Section | Specific Location | Percent of Total Weight |

| Lower body | Foot | 1.5% |

| Calf and foot | 5.9% | |

| Entire lower extremity | 16% | |

| Upper body | Hand | 0.7% |

| Forearm and hand | 2.3% | |

| Entire upper extremity | 5% | |

Transgender Patients

Hormonal therapy influences lean body mass and should be considered when estimating renal function in transgender patients. For transgender patients who have completed at least six months of hormone therapy, the team should calculate CrCl using their gender identity, not their sex assigned at birth.9

PAUSE AND PONDER: In what situations should heparin be used to protect the patient from thrombosis while oral anticoagulants are held for surgery?

CHEST GUIDELINE

CHEST released an updated Clinical Practice Guideline for the Perioperative Management of Antithrombotic Therapy in 2022.10 The new more user-friendly guideline replaces the 2012 version.11 It only provides guidance for elective procedures that are not urgent. The 2022 version provides more comprehensive and detailed guidance on the perioperative use of DOACs, antiplatelet medications, and heparin bridging. It also includes more specific guidance on perioperative risk of thrombosis and bleeding.

Many CHEST Guideline recommendations are presented as being supported by either "Low" or "Very Low" Certainty of Evidence. For these, individual patient characteristics and clinical judgment become more important when determining a plan of action. The main body of the text sometimes describes specific considerations for different patient populations.

The CHEST Guideline only makes two strong recommendations, both regarding warfarin10:

- Prescribers should not bridge patients using warfarin with LMWH when atrial fibrillation (AF) is the sole indication.

- Warfarin should be continued, not held, for ICD or pacemaker placement if the international normalized ratio (INR) is less than 3.0.

It makes several other important recommendations10:

- Warfarin patients at high risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) should be bridged with heparin.

- Avoid heparin bridging for patients who take DOACs.

- Avoid heparin bridging for warfarin patients with minimal to moderate risk of VTE with the following:

- Mechanical heart valves

- VTE as the only risk factor (post-procedure low-dose heparin may be used)

- A colonoscopy with polypectomy

- Avoid adjusting

- LMWH or DOAC dosing to anti-Xa levels

- Antiplatelet medications based on antiplatelet testing

- Discontinue apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban before procedures.

- Continue aspirin (ASA) for patients having non-cardiac surgery.

- Patients who take ASA and have coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) scheduled should continue ASA.

- Patients who take dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) who had a coronary artery stent placed six to 12 weeks ago should either continue both antiplatelet agents or should hold one of them seven to 10 days pre-procedure.

- DAPT patients who had a coronary artery stent placed three to 12 months ago, and patients who are having CABG surgery, should hold their P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor, or cangrelor).

- Do not use glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors (eptifibatide, tirofiban) or cangrelor to bridge antiplatelet patients.

- When holding a DOAC, continue holding until at least 24 hours post-procedure, as restarting sooner can increase bleeding risk.

- Patients with an INR above 1.5 up to two days before the procedure should not receive vitamin K as this can delay return to full therapeutic INR post-procedure.

- Continue warfarin for dental procedures.

- Exceptions: Hold warfarin if the patient has poor gingival condition or is expected to bleed profusely. Consider patient history.

- Tranexamic acid and additional sutures can be used to limit bleeding.

- Continue warfarin for minor dermatologic procedures.

- Exceptions: Hold warfarin if the patient is having a skin graft or expected to bleed profusely.

- Continue warfarin for minor ophthalmologic procedures.

- Exceptions: Retinal surgery or any time retrobulbar anesthesia is used

Practice Pearl: It can be challenging to find information that applies to a highly specific patient population in a dry document like a CHEST Guideline. This is an optional exercise: under what heading in the CHEST Guideline does it describe specific patient characteristics that may make you inclined to hold an anticoagulant or antiplatelet drug for a dental extraction?

- Assessing Perioperative Risk for Surgery/Procedure Related Bleeding

- Summary of Key Recommendations

- Patients Having a Minor Dental, Dermatologic, or Ophthalmologic Procedure

Table 3 summarizes CHEST Guideline recommendations for how long to hold an anticoagulant before a procedure and when to resume it after a procedure.10

| Table 3. Recommended Perioperative Anticoagulant Holding Times10 | ||||

| Anticoagulant | Procedure Bleed Risk | How Long to Hold Before Procedure | When to Resume Post-Procedure | Post-Procedure Notes |

| Warfarin | - | 5-6 days | Within 24 hours | - |

| IV UFH (therapeutic dose) | - | At least 4 hours | At least 24 hours | No bolus. Target a lower aPTT. |

| LMWH | Low-moderate | Half the total daily dose in AM, 24 hours prior | At least 24 hours | - |

| High | 24 hours | At least 48-72 hours | If needed, low-dose LMWH may be used for the first 2-3 days. | |

| Apixaban | Low-moderate | 1 day | All DOACs:

At least 24 hours post procedure after low-moderate risk

At least 48-72 hours after high risk |

|

| High | 2 days | |||

| Dabigatran | Low-moderate,

CrCl at least 50 mL/min |

1 day | ||

| Low-moderate, CrCl less than 50 mL/min | 2 days | |||

| High risk, CrCl at least 50 mL/min | 2 days | |||

| High risk, CrCl less than 50 mL/min | 4 days | |||

| Edoxaban | Low-moderate | 1 day | ||

| High risk | 2 days | |||

| Rivaroxaban | Low-moderate | 1 day | ||

| High risk | 2 days | |||

| ASA | - | At least 7 days* | *Evaluate whether antiplatelet agents need to be held at all on a case-by-case basis. | |

| Clopidogrel | - | At least 5 days* | ||

| Ticagrelor | - | 3-5 days* | ||

| Prasugrel | - | 7 days* | ||

PAUSE AND PONDER; How do clinicians decide who is at high enough risk of thromboembolism to interrupt anticoagulation for a surgery or procedure or to warrant the additional bleeding risk of LMWH during a warfarin bridge?

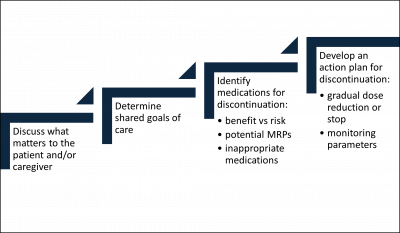

PATIENT-SPECIFIC PERIOPERATIVE ANTICOAGULATION PLAN

Overview

Step 1: Begin by collecting basic information:

- What procedure or surgery is happening, and when?

- Which anticoagulant is the patient using?

- What herbal and vitamin supplements are the patient currently taking?

- What is the patient's medical history and allergies? Are there any recent updates from either inside or outside your healthcare system?

- Does the patient have a history of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), severe bleeding such as SDH, thrombosis, or other complications during a historical perioperative period?

- Do you need to update the patient's weight or lab work?

Step 2: Communicate with other healthcare team members involved in this patient's care.

Step 3: Assess risks and prepare the perioperative plan.

- Assess the risk of thrombosis. Is holding the anticoagulant really necessary? How long? Is bridging required?

- Assess the risk of procedure-related bleeding.

- Calculate renal function and Child-Pugh score if applicable.

- Obtain or place orders as necessary following the institution's protocol.

- Review plan for feasibility and accuracy. Examples of potential errors include

- Bridging warfarin patients in end stage renal disease (ESRD) with therapeutic-dose LMWH

- Bridging DOAC patients with LMWH

- Holding warfarin for 5 days without LMWH bridging in mechanical mitral valve replacement (MVR) patient with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), a history of VTE, with low bleeding risk

- Holding warfarin 7 days before a single dental extraction in patients with paroxysmal AF

- Holding warfarin 1 day before spinal surgery

Step 4: Educate the patient and/or caregiver.

A written plan can facilitate adherence and communication between team members and the patient, especially if the plan is complicated. Clinicians who review the plan verbally with patients can evaluate feedback and clarify questions instantly. If applicable, patient education should cover subcutaneous injection technique and sharps disposal. Confirm that patients and caregivers understand the plan using the teach-back technique and spot-checks. A critical element is how to recognize the signs of bleeding or thrombosis with patients, so the patient knows when to call 911.

Practice Pearl: The electronic health record (EHR) often contains errors or omissions. Reviewing medication and problem lists with patients may identify medication that was discontinued (sometimes years ago!). Sometimes, patients do too much yard work and injure a knee; they start ibuprofen without notifying their healthcare provider. Perhaps they visited London and didn’t tell their provider about the pulmonary embolism they developed on the flight, or the fact that they are now using rivaroxaban. They may have been hiking in the Grand Canyon when they had a myocardial infarction and didn’t think to mention they are now using clopidogrel and aspirin. Clinicians will not know unless they ask.

OVER-THE-COUNTER PRODUCTS

Many foods and over-the-counter (OTC) products can increase bleeding risk and should be held in the perioperative period. Table 4 shows a sample of interactions between foods/supplements and selected anticoagulants. For example, using cannabidiol (CBD) with apixaban can increase the patient's bleeding risk; if patients who have a high bleeding risk procedure restart apixaban and CBD after the procedure, bleeding risk will be high during that time.

Some supplements and foods have intrinsic anticoagulant or antiplatelet properties and can increase the bleeding risk even wihout a CYP450 or P-glycoprotein interaction. St. John’s Wort can increase risk of thrombosis when used with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and warfarin; it induces CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein. When in doubt, it is generally best to err on the side of caution and hold all patient-initiated supplements in the perioperative period.

Practice Pearl: Surgeons often require tobacco cessation before scheduling surgery. This can increase warfarin sensitivity through a CYP1A2 interaction.

Cannabis is widely used. It is primarily metabolized by the liver, but about a fifth is renally eliminated. It inhibits CYP450 enzymes, including 3A4, 2D6, 2C9, and 2C19. In addition to its potential interactions with anticoagulants, it can also prolong sedation and increase the risk of myocardial ischemia. Patients with cannabis use disorder can experience increased perioperative morbidity and mortality.12-14

| Table 4. Interactions Between OTCs and Common Anticoagulants15-19 | |||||||||

| OTC Product | Possible Intrinsic Antiplatelet Activity | Possible Intrinsic Anticoagulant Activity | Apixaban | ASA | Clopidogrel | Enoxaparin | Dabigatran | Rivaroxaban | Warfarin |

| Aspirin | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Alpha-lipoic acid | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Berberine | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Black seed | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Cannabidiol | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Chamomile | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Cocoa | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Danshen | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Dong quai | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Echinacea | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Eucalyptus | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Feverfew | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Garcinia cambogia | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Garlic | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Ginger | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Gingko biloba | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Ginseng (American) | x | ||||||||

| Ginseng (Panax) | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Grapefruit | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Ibuprofen* | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Jackfruit | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Lime | x | x | x | x | |||||

| Melatonin | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Naproxen* | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Turmeric | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Vitamin E | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Yerba mate | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

*Ibuprofen and naproxen may block antiplatelet effect of ASA.

PERIOPERATIVE RISK ASSESSMENT

The following risk stratification methods are general guides, not absolute rules. Pharmacists must consider the whole patient and use good clinical judgement. Caution and prioritizing patient safety are always prudent.

Risk of Thrombosis

Certain patient characteristics increase a patient’s risk of thrombosis during a procedure. The CHEST Guideline presents three main risk categories: AF, VTE, and mechanical heart valves. When a patient has an elevated risk score in multiple categories, the team should use the highest value for stratification purposes. For example, if a patient has a CHA2DS2VASc score of 2 and antiphospholipid antibodies, classify the patient as high risk of thrombosis.

Atrial Fibrillation

The CHADS2 and CHA2DS2VASc scoring formulas classify patients with AF as having a high, medium, or low risk of stroke as described in Table 5. the CHEST Guideline references both:

- CHADS2: Add one point for each of the following conditions: congestive heart failure (CHF), hypertension, age at least 75 years, and diabetes; add two points for a history of stroke/TIA.

- CHA2DS2VASc: Add one point for each of the following conditions: CHF, hypertension, diabetes, vascular disease (myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, aortic plaque), age 65-74 years, and sex category of female; add two points each for age at least 75 years and history of cerebrovascular accident (CVA)/TIA/thromboembolism.

CHA2DS2VASc identifies low-risk patients more accurately and classifies fewer patients as moderate risk.20

| Table 5. Risk of Thrombosis Secondary to Atrial Fibrillation10 | ||

| High | Moderate | Low |

| CHADS2: 5-6

CHA2DS2VASc: at least 7 CVA/TIA in the past 3 months Rheumatic valvular heart disease |

CHADS2: 3-4

CHA2DS2VASc: 5-6

|

CHADS2: 0-2 (no CVA/TIA)

CHA2DS2VASc: 1-4

|

Source: Adapted from reference 10 p.e212.

Venous Thromboembolism

| Table 6. Risk of Thrombosis Secondary to Hypercoagulable States. | ||

| High Risk | Moderate Risk | Low Risk |

| VTE within the past 3 months

Protein C or S deficiency Antithrombin deficiency Homozygous Factor V Leiden Homozygous gene G20210A mutation Antiphospholipid antibodies Active brain, gastric, pancreatic, or esophageal cancer Myeloproliferative disorders |

VTE 3-12 months prior

Recurrent VTE Heterozygous Factor V Leiden Heterozygous gene G20210A mutation Active or recent malignancy other than those specifically listed in high risk category |

VTE more than 12 months prior |

Mechanical Heart Valves

| Table 7. Risk of Thrombosis Secondary to Mechanical Heart Valves10 | ||

| High Risk | Moderate Risk | Low Risk |

| MVR + major risk factor(s)*

Caged-ball, tilting-disc AVR/MVR CVA/TIA within the past 3 months |

MVR without major risk factors*

AVR (bileaflet) with major risk factors |

AVR (bileaflet) without major risk factors* |

*Major risk factors for CVA: History of AF, CVA/TIA during previous anticoagulation hold, rheumatic heart disease, valve thrombosis, HTN, diabetes, CHF, age 75 or greater.

Bleeding Risk

Some patients develop serious bleeding during or after a procedure, so risk assessment is critical. The literature describes several different bleeding-risk scoring systems, including HAS‐BLED, HEMORR2HAGES, ORBIT‐AF, ATRIA, and GARFIELD‐AF. In short, while these tools can help identify potentially high-bleeding-risk patients, their accuracy varies depending on the patient population studied.21,22 The CHEST Guideline includes empiric classification guidance.10

High

Generally, surgeries and procedures performed on highly vascularized organs, that cause extensive tissue damage, or are spinal-invasive are considered high risk. Anticoagulants should be held long enough to reverse their effects. Examples include

- Cancer

- Cardiac

- Colonic polyp or bowel resection

- Epidural injections

- Gastrointestinal (GI)

- Kidney

- Major orthopedic

- Major thoracic

- Neuraxial interventions

- Reconstructive plastic

- TURP

- Urologic

Low to Moderate

These surgeries are considered low to moderate bleeding risk surgeries and procedures, regardless of whether biopsies are performed. Anticoagulants can be held for less time during the perioperative period.

- Arthroscopy

- Bronchoscopy

- Colonoscopy

- Coronary angiography, femoral approach

- Foot, hand

- GI endoscopy

- Hemorrhoidal surgery

- Hysterectomy

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Lymph node biopsies

Minimal

Many patients can remain fully anticoagulated for minimal bleeding risk procedures, although it would be reasonable to consider holding a DOAC on the day of the procedure. In certain circumstances, such as a dental extraction in a patient who has poor gingival health, it may be reasonable to hold anticoagulation before a minimal bleed risk procedure.

- Cataract procedures

- Coronary angiography, radial approach

- Minor dental procedures, including extraction(s)

- Minor dermatologic procedures, including excision of skin cancers

- Pacemaker or ICD placement

DIRECT ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

Since heparin bridging is not used for patients who use DOACs, these instructions are simple. Clinicians should provide patients with instructions to hold their DOAC on specific dates. However, they need to know the audience! For some patients, verbal communication suffices. In this case, the best practice would be to ask the patient to repeat the instructions to confirm understanding. Other patients find it more helpful to have written instructions, especially those who have caregivers. For patients who live in assisted living facilities that manage their medications, pharmacists can do two things: (1) review the instructions with the patient for their own knowledge and (2) provide instructions directly to the facility.

DOACs only take a few hours to become fully effective. Ask the patient to check with the surgeon after the procedure is complete to make sure it’s safe to restart the DOAC.23

WARFARIN

The inter-patient variability in responses to warfarin cannot be understated. Warfarin’s half-life is 20 to 60 hours and varies significantly from patient to patient. Warfarin ultimately inhibits activation of clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X, and it also affects the natural anticoagulants protein C and S. Table 8 compares these factors’ half-lives and reveals that they are not necessarily pivoting in concert while warfarin doses are being adjusted.

| Table 8. Half-lives of Clotting Factors Relevant to Warfarin Use | |

| Factor | Half-life (hours) |

| II | 42-72 |

| VII | 4-6 |

| IX | 21-30 |

| X | 27-48 |

| Protein C | 8 |

| Protein S | 60 |

Source: Adapted from 24 p. 20.

Many factors affect a patient's response to a warfarin dose. These include interactions with diet, pharmacokinetic medication interactions, pharmacodynamic interactions, liver function, edema status, and many more. Surgery and hospitalization commonly cause physical stress and decrease appetite; both increase warfarin sensitivity. The patient's history can be invaluable when determining post-procedure doses but caution is warranted. Even if the patient had a similar warfarin holding situation in the past available for comparison, they may respond differently this time.

It can take three to seven days (or more) to see the effect of warfarin dosing changes on the INR. Therefore, patients usually resume warfarin in the evening after a procedure is completed. It can take weeks for INR to stabilize after major surgery. This is when shorter-acting LMWH and unfractionated heparin (UFH) become useful.

Heparin Bridging During Warfarin Interruption

Unless otherwise specified, when the CHEST Guideline mentions "heparin bridging," it specifically refers to using a therapeutic-dose LMWH. Examples include enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily or 1.5 mg/kg daily, dalteparin 100 international units/kg BID or 200 international units/kg daily, or full-dose UFH to achieve target aPTT of 1.5-2x the control, or a target anti-Xa level of 0.35 to 0.70 international units/mL. Lower prophylactic or intermediate doses may be used in certain circumstances.10 Clinicians need to calculate renal function before finalizing a dose. If a patient with ESRD needs to bridge for a procedure, it is best to use IV UFH for inpatient bridging rather than LMWH.

Practice Pearl: It may be difficult for patients who are underweight (with little subcutaneous fat) or who have had major surgery (scarring or local trauma) to find suitable sites for subcutaneous injections.

Practice Pearl: It can be challenging to determine an appropriate therapeutic dose of LMWH for patients with BMI exceeding 40 kg/m2, especially in the outpatient setting, where monitoring anti-Xa levels would be more challenging. Whether or not to cap the dose at some amount lower than 1 mg/kg twice daily is a controversial topic.14,25

Practice Pearl: Procedures that require LMWH bridging and are scheduled without much notice can cause logistical challenges for patients. Questions to consider include

- When does the patient need to start using LMWH?

- Does the pharmacy have it in stock?

- If not, how long will it take them to order it?

- Will the patient be able to afford the copay?

Practice Pearl: Significant drops in hemoglobin, hematocrit, or platelets after a surgery or procedure can be the first warning sign of severe post-operative bleeding.

Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a potentially life-threatening condition that is a possible reaction to heparin. The ASH Guideline suggests monitoring for drops in platelet count for patients who are considered to have moderate or high risk of HIT, including patients using UFH and patients using LMWH after major surgery or trauma. In these cases, the guideline recommends monitoring platelet count every two to three days until heparin is discontinued.26

Example Warfarin Bridge Plan

Oliver is a 52-year-old male patient with a MVR, antiphospholipid antibodies, and a history of CVA. He has a colonoscopy scheduled next month. Lab work done 9 months ago was largely unremarkable, except his platelets were 30 points below the minimum EHR reference range (unknown etiology). His medication list includes warfarin 5 mg daily, lisinopril 20 mg daily, and aspirin 81 mg daily. He said he does not use supplements. His INR has been stable and therapeutic for the past two months. He has had no other procedures in the past year. Repeat bloodwork indicates his platelets are now within normal limits. He will return home the same day as the procedure.

Vitals: Weight 174 lb, BP 135/82 mmHg. CrCl 65 mL/min.

Your institution's protocol indicates he should bridge with therapeutic dose enoxaparin for this procedure, and you have whatever approvals you need to proceed. You send a prescription for 80 mg enoxaparin syringes #20 to his local pharmacy, to be used twice daily as instructed in Table 9. Since his procedure is still a month away, his pharmacy has time to order the enoxaparin if necessary.

| Table 9. Example Patient Instructions for Perioperative Anticoagulation | ||||

| Month | Day | Day of Week | Warfarin Dose | Injectable Anticoagulant: 80 mg Enoxaparin |

| Apr | 17 | Thursday | Last dose: 5 mg | None |

| Apr | 18 | Friday | None | None |

| Apr | 19 | Saturday | None | None |

| Apr | 20 | Sunday | None | Begin enoxaparin injections under the skin every 12 hours, starting this morning |

| Apr | 21 | Monday | None | Continue enoxaparin injections every 12 hours |

| Apr | 22 | Tuesday | None | Continue enoxaparin injections, just once today, with the last dose at least 24 hours before the procedure |

| Apr | 23 | *Procedure* Wednesday | If the surgeon approves, restart after procedure is complete with 7.5 mg | None |

| Apr | 24 | Thursday | 7.5 mg | If the surgeon approves, restart enoxaparin injections, just once today, starting 24 hours after procedure is complete |

| Apr | 25 | Friday | 5 mg | Continue enoxaparin injections every 12 hours |

| Apr | 26 | Saturday | 5 mg | Continue enoxaparin injections every 12 hours |

| Apr | 27 | Sunday | 5 mg | Continue enoxaparin injections every 12 hours |

| Apr | 28 | Monday | Further instructions are to be provided at today's appointment | Continue enoxaparin injections, but please wait until after this morning's visit before using enoxaparin today to allow for fingerstick INR |

| Please continue injections until the Anticoagulation Clinic asks you to stop. Your next appointment is 4/28/25. On days when you are scheduled for a post-procedure INR check, please hold your morning injection until after your morning appointment. If you will be doing errands after your visit, please bring a syringe with you to stay on schedule with your injections. | ||||

PAUSE AND PONDER: How would you provide instructions to the patient in a way that they both understand and are willing and able to follow?

COMMUNICATION TECHNIQUES

Practice Pearl: Use active listening, reflective statements, and motivational interviewing techniques to ensure patients know you hear their concerns and are comfortable asking questions.

In the ambulatory setting, the patient must fully understand and accept the perioperative plan to minimize the risk of harm. Patients may not follow through if they think the team doesn’t care about their concerns.

Consider Emma, who has been your patient for several years. She arrives at the clinic irritated and you do not know why. You try to make small talk with her, but she snaps, “Just get on with the visit.” She crosses her arms across her chest and looks away. You do not know this yet, but her mother was just diagnosed with metastatic colon cancer and is considering foregoing treatment and entering hospice care.

Emma is here today to review perioperative instructions for her upcoming colonoscopy. She has had precancerous polyps removed in the past and has recently developed a small amount of hematochezia (presence of fresh [bright red] blood in stools). Emma was not expecting to have to bridge for her colonoscopy because she didn’t bridge for the last one. She recently established care with a new provider who is more concerned about her risk of thrombosis than her last one was.

She is expecting to hold her warfarin five days prior to her procedure and restart it the same evening, but then you show her a detailed calendar of LMWH bridging instructions and begin reviewing them. She becomes increasingly disengaged and even a little tearful and refuses to follow the plan. She says, “Forget it. I am cancelling the colonoscopy.”

The sooner you identify a bad situation developing, the easier it is to avert it. The patient's body language is a signal to address concerns immediately. The moment Emma crossed her arms across her chest and looked away was your cue to stop and attempt to determine the problem. If she shares her concern about her mother’s recent diagnosis and her concerns about her own health, use a reflective statement (summarize and repeat the problem back to her). Don’t judge, contradict, or redirect her. Demonstrate you are really listening to her and trying to understand her concerns. She will probably uncross her arms and make eye contact with you again.

At an appropriate time, gently guide the discussion back to the reason she is here. You might say something like, "Thank you for sharing your concerns. I hear that you are feeling very stressed right now. You only want the best for your mother, and this news is devastating. You’re worried about what the doctor will find in your own colonoscopy. I went right into all these details about a complicated, unexpected bridge plan. I would feel anxious myself if I were you. I want you to know that you are always in control of your own healthcare. You get to decide for yourself if you want to proceed, if and when you are ready. If it turned out that you have another polyp, would you want to have the opportunity to have it removed?"

While you are having this discussion, it is important to remain attentive and welcome her to interrupt you with new information or questions or concerns as they come up. Emma agrees to proceed, and you review the instructions with her. After presenting the plan, ask her to explain to you what she will be doing at each step of the process to confirm understanding. This is called a “teach-back technique.”

Practice Pearl: Use teach-back techniques and spot-checking to ensure understanding.

Language Barriers and Hearing Impairment

Practice Pearl: Use only qualified interpreters when communicating complicated instructions to patients who do not share your native language. Use alternate communication methods as needed for deaf or hard-of-hearing patients.

Patients may find it more difficult to understand instructions that contain slang or medical jargon. Sometimes, patients nod to indicate they understand what you are saying, even when they do not, to be polite or to avoid social discomfort. When using interpreters, make eye contact with and speak directly to the patient, not the interpreter. Speaking louder will not improve understanding when the obstacle is a language barrier. Patients with hearing impairment may benefit from careful enunciation, especially of consonants. They may also lip-read, even if they do not realize they are doing it. This can be challenging in situations when masking is required.

Practice Pearl: In the United States, the format frequently used to describe dates is month-day-year; however, other countries use day-month-year. To minimize confusion, provide written dates with the month shown as a word instead of a number, e.g., “August 3” instead of “8-3.”

Cognitive Impairment

Practice Pearl: Be prepared to repeat your instructions as often as needed to ensure understanding.

Cognitive impairment occurs across a broad spectrum that can make it challenging for patients to understand and/or follow detailed instructions.27 Some patients may need to review the material with you several times. Other patients may bring a caregiver or friend to help them think of questions to ask and to remember their instructions. Some patients cannot take their medication on their own; in this case, it is essential to provide education to a caregiver who can help them navigate the process. If caregivers accompanies a patient to an appointment, acknowledge their presence and include them in the discussion. They may have relevant questions, concerns, or valuable feedback.27

The following resources provide more tips on patient communication:

- https://www.cds.udel.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/effective-communication.pdf

- https://store.jointcommissioninternational.org/assets/3/7/jci-wp-communicating-clearly-final_(1).pdf

Vision Impairment and Tremor or Arthritis

Practice Pearl: Round a dose to the nearest commercially available dose instead of strict weight-based dosing.

The more complicated or physically challenging the perioperative instructions are, the greater the risk of dosing errors. For example, enoxaparin syringes are graduated but the small markings may be hard for patients with vision impairment to see. Additionally, tasks requiring fine motor skills, such as removing a tiny amount of liquid from a syringe, or even administering an injection, may be difficult or impossible for patients with tremors or arthritis. Dose rounding to the nearest commercially available strength can help with this.

Enoxaparin comes in the following prefilled syringe doses: 30, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, and 150 mg.28

Common Patient Misconceptions

Practice Pearl: To prevent patient misunderstandings, explain the independent roles of warfarin and LMWH in the bridge and why both are used simultaneously.

Sometimes, patients misunderstand the role of warfarin and LMWH in the bridging process, even when they have detailed written instructions. They may not resume LMWH post-procedure because they think their INR will return to their therapeutic range immediately after restarting warfarin. They may not resume warfarin post-procedure because they believe the LMWH increases their INR. You can prevent these kinds of misunderstandings by providing a basic explanation of the independent roles of warfarin and LMWH in the bridge, and why they will be using both at the same time post-procedure.

Practice Pearl: Ask patients to "hold" the anticoagulant on specific dates (and resume it on specific dates). Do not use the term "stop." If you tell patients to stop their warfarin on Tuesday, they might take that to mean you want them to take their last dose of warfarin on Tuesday, not to take the last dose of warfarin on Monday and start holding it on Tuesday. This misunderstanding can result in a patient holding warfarin for only four days before their procedure, instead of five

Revisions Due to Unexpected Developments

Clinicians involved in anticoagulation must remain flexible and prepared to adapt to an evolving situation after a patient’s surgery or procedure. Some common examples of periprocedural situations that may warrant closer monitoring post-procedure include

- Bleeding may delay the resumption of anticoagulation post-procedure.

- NSAIDs prescribed for pain control on discharge can increase bleeding risk.

- Vitamin K reversal increases warfarin dosing requirements post-procedure.

- Reduced appetite or food intake post-procedure may reduce rivaroxaban absorption or increased warfarin sensitivity.

- Bariatric surgery can have unpredictable effects on warfarin dosing requirements. Although patients are eating less, they may have initiated supplements that contain more vitamin K than they consumed pre-procedure.

- Dental procedures can temporarily decrease food intake; however, some dentists ask patients to use protein shakes (many of which contain vitamin K) post-procedure.

- Tobacco cessation increases warfarin sensitivity

- Changes in kidney or liver function may affect medication clearance.

CONCLUSION

Assembling an appropriate perioperative plan for a patient's anticoagulation can be complicated. The material and pearls provided in this activity can help clinicians devise and implement a plan that is appropriate for each patient.

Program Handouts

Post Test

View Questions for Perioperative Management of Warfarin Interruption

1. Which of the following patients should be bridged for a hip replacement surgery?

a. A 46-year-old male who uses a DOAC for atrial fibrillation

b. A 38-year-old female who uses warfarin for heterozygous Factor V Leiden mutation

c. A 42-year-old male who uses warfarin for Protein S deficiency

2. Which of the following surgeries carries the highest risk of perioperative bleeding?

a. Colonic polyp resection

b. Hemorrhoidal surgery

c. Hysterectomy

3. Which of the following patients has the highest risk of perioperative thromboembolism, assuming all medical conditions are listed?

a. A 34-year-old female with antiphospholipid antibodies

b. A 75-year-old female with atrial fibrillation and aortic plaque

c. A 65-year-old male with atrial fibrillation, history of stroke, and hypertension

4. A 26-year-old Ukrainian patient who does not speak English comes to your clinic to review perioperative instructions for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy next week. His only other medical condition is asthma. You have arranged for a professional interpreter to attend today’s visit. While using the interpreter, which of the following will help the patient understand your instructions?

a. Increasing your voice’s volume so he can hear what you are saying

b. Making eye contact and speaking directly to the patient

c. Using medical jargon and using highly technical terms

For the next two questions, consider the following patient case:

Evelyn is a 50-year-old female patient with an MVR, diabetes, protein C deficiency, Crohn’s disease, and hypertension. She has a bowel resection scheduled. Her current medications include warfarin, metformin, losartan, aspirin 81 mg, and prednisone. She also uses a daily multivitamin and alpha lipoic acid.

5. Which of the following perioperative plans would be most appropriate?

a. Hold both warfarin and ASA for seven days before the surgery, bridge with therapeutic dose LMWH, with the last pre-surgery LMWH dose, at half the total daily dose, 48 hours before the surgery and restarting LMWH 24 hours after the procedure if hemostasis is achieved. Continue ASA and alpha lipoic acid for the surgery.

b. Hold warfarin for five days before the resection and restart warfarin the evening of the surgery with no LMWH bridging if hemostasis is achieved. Hold the aspirin and alpha lipoic acid starting the week before until at least a week after the surgery.

c. Hold warfarin for five days before the surgery, bridge with therapeutic dose LMWH, at half the total daily dose, with the last pre-surgery LMWH dose 24 hours before the surgery and restarting LMWH 48 hours after the surgery if hemostasis is achieved. Continue ASA but hold alpha lipoic acid starting the week before until at least a week after the surgery.

6. If Evelyn was having a pacemaker placement instead of a bowel resection, which of the following perioperative plans would be most appropriate?

a. Hold warfarin for five days before the surgery, bridge with therapeutic dose LMWH, with the last pre-procedure LMWH dose, at half the total daily dose, 24 hours before the procedure and restarting LMWH 48 hours after the surgery if hemostasis is achieved. Continue ASA but hold alpha lipoic acid starting the week before until at least a week after the surgery.

b. Continue warfarin and ASA for the procedure but hold alpha lipoic acid starting the week before until at least a week after the surgery.

c. Hold both warfarin and ASA for seven days before the surgery, bridge with therapeutic dose LMWH, with the last pre-surgery LMWH dose, at half the total daily dose, 48 hours before the surgery and restarting LMWH 24 hours after the procedure if hemostasis is achieved. Continue ASA and alpha lipoic acid for the surgery.

7. Lily is a 78-year-old female with atrial fibrillation, CHF, and hypertension. She has a Watchman left atrial appendage closure device and a history of hemorrhagic stroke. Her current medications include sacubitril/valsartan and ASA. If she were to have an epidural injection, which of the following supplements would you be most concerned about her using during the perioperative period?

a. Echinacea

b. Gingko biloba

c. Grapefruit

8. John is a 67-year-old male who is scheduling a TURP. His medications include apixaban 5 mg BID, tamsulosin 0.4 mg daily, and metoprolol tartrate 50 mg BID. What is the minimum number of hours John would need to hold apixaban before the surgery?

a. Hold apixaban starting 12 hours before the surgery and restart no sooner than 24 hours after the surgery

b. Apixaban does not need to be held for this surgery

c. Hold apixaban starting 48 hours before the surgery and restart no sooner than 48 hours after the surgery

The following two questions are about the following patient case: Samantha is a 72-year-old female who lives alone and is 5’ 8” and weighs 210 lb. She uses topical diclofenac gel for arthritis. She also uses a daily multivitamin. She had a lab draw last month that was within normal limits. Her serum creatinine was 1.64 mg/dL. She is having hip replacement surgery in two weeks.

9. If she uses warfarin for antithrombin deficiency, what would be the most appropriate enoxaparin dose for her to use as an outpatient?

a. 95 mg

b. 40 mg

c. 100 mg

10. If she used a DOAC, which of the following would need to be held four days before the procedure?

a. Apixaban

b. Rivaroxaban

c. Dabigatran

Additional Courses Available for Anticoagulation

Vitamin K Antagonist Pharmacology, Pharmacotherapy and Pharmacogenomics – 1 hour

Anticoagulation Management Pearls - 1.5 hour

Clinical Overview of Direct Oral Anticoagulants– 1.25 hour

Laboratory Monitoring of Anticoagulation – 2 hour

Heparin/Low Molecular Weight Heparin and Fondaparinux Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapy – 0.5 hours

Developing an Anticoagulation Clinic – 1.0 hour

Pharmacist Reimbursement for Anticoagulation Services – 0.5 hour

Risk Management in Anticoagulation – 1 hour

A Practical Approach to Perioperative Oral Anticoagulation Management – 2 hour

Management of Hypercoagulable States – 1.5 hour

Challenging Topics in Anticoagulation – 2 hour

Available Strategies to Reverse Anticoagulation Medications - 2 hour

Drug Interaction Cases with Anticoagulation Therapy – 1 hour