INTRODUCTION

Ray and Kai are pharmacists that work together in a very busy outpatient clinic pharmacy. On a typical day, they fill around 800 prescriptions, and they usually have help from three technicians. Unfortunately, if anyone calls out sick or with an emergency, they don't have backup coverage.

Several times a week, patients return to the pharmacy and indicate that the prescriptions they received don't seem to be correct. Occasionally, Ray and Kai discover a medication error when patients indicate that their tablets or capsules don't look the same as a previous refill. Just yesterday, a mother returned to the pharmacy because her child’s liquid amoxicillin/clavulanate ran out before it should have. When Kai examined the label, she found a typographical error; it said, “take 5 mL three times a day” when it should have said, “take 2.5 mL three times a day.”

When staff members in this pharmacy identify medication errors, they usually discuss the problem quietly with the involved staff and make a mental note to implement corrective action or pay closer attention. Their pharmacy’s workload, staffing, error rate, and method of dealing with medication errors is not much different than many pharmacies across our nation. Throughout this continuing education activity, this example and others will help learners apply the lessons that experts have learned from analyzing medication errors.

Patient safety is a cornerstone of quality healthcare, and pharmacy professionals have an obligation to ensure patients receive safe and effective medications. Medication errors often stem from communication gaps, system complexities, or improper medication use. These errors not only compromise patient outcomes but also contribute to increased healthcare costs and increase risks of medication-related adverse effects.1

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) tallies and analyzes medication error reports from the National Medication Errors Reporting Program, which is administered by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). NCC MERP defines a medication error as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm.” Medication errors occur at various stages of the medication-use process, from prescribing and dispensing to administration and monitoring.2 Recognizing these errors and implementing prevention strategies are essential to improving patient safety and advancing pharmacy practice.

OVERVIEW OF MEDICATION ERRORS

To truly appreciate medication errors’ impact on patients, pharmacy team members must recognize common terms and types of errors.

Medication Error Terminology

Several medication errors can arise in clinical and retail settings. To actively prevent patient injury through medication errors, it is important to know what to look for in practice. Terms to be familiar with in all pharmacy practice settings include3,4:

- Adverse drug event (ADE): An injury resulting from medical intervention related to a drug

- Adverse drug reaction (ADR): An unintended reaction occurring at the intended drug dose

- High-alert medications: Drugs that bear a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used in error

- Look-alike/sound-alike (LASA) medications: Medications with similar-looking or similar-sounding names and/or shared features of products or packaging, leading to potential confusion

- Medication reconciliation: The process of creating the most accurate list possible of all medications a patient is taking—including drug name, dosage, frequency, and route—and comparing that list against the physician's admission, transfer, and/or discharge orders, with the goal of providing correct medications to the patient at all transition points

PAUSE AND PONDER: When an error is identified, how does your pharmacy respond?

Defining and Classifying Medication Errors

Table 1 lists common medication errors that may occur throughout the stages of medication use.4

Table 1. Common Medication Errors4

| Error Type |

Description |

Examples |

| Prescribing |

Errors occurring when ordering medication |

Wrong drug selection, incorrect dose/frequency, illegible handwriting, incomplete prescription, drug interactions |

| Dispensing |

Errors occurring during medication preparation and distribution |

Wrong medication, wrong strength, wrong dosage form, incorrect labeling, look-alike/sound-alike drug confusion |

| Administration |

Errors occurring during drug administration to the patient |

Wrong route, wrong dose, wrong rate, omission, administering to the wrong patient |

| Monitoring |

Errors occurring due to lack of proper patient monitoring |

Failure to monitor for adverse effects, inadequate lab test follow-up, failure to adjust dose for renal/hepatic function |

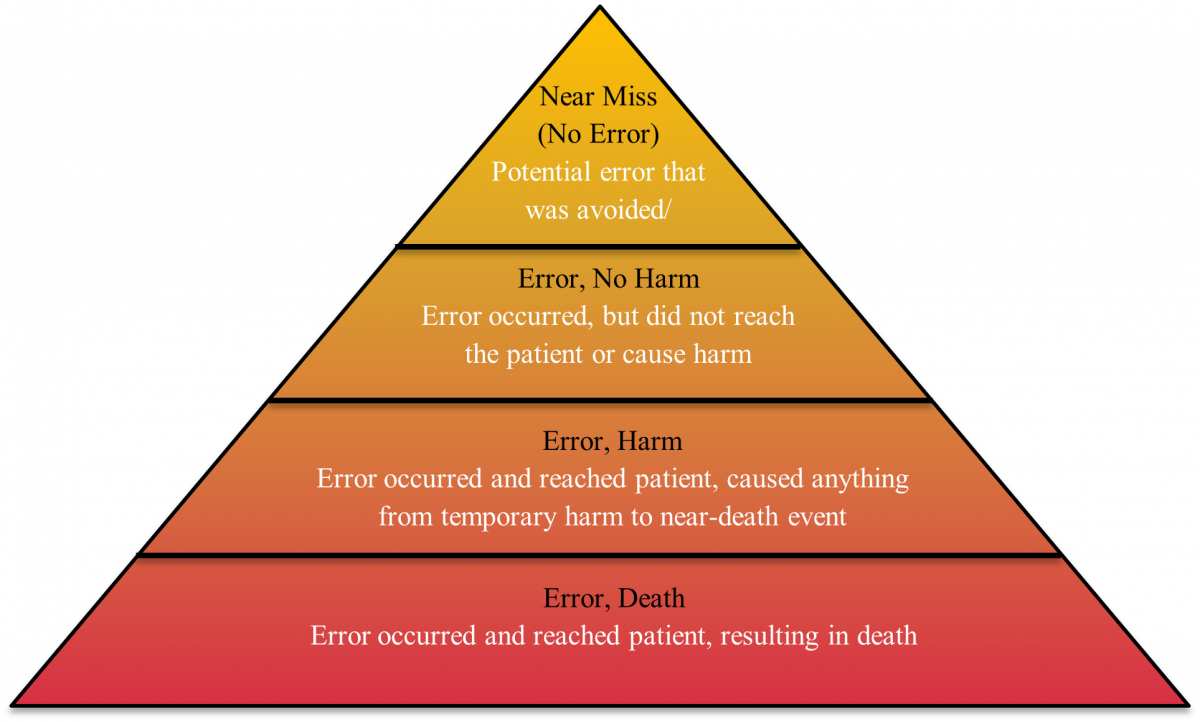

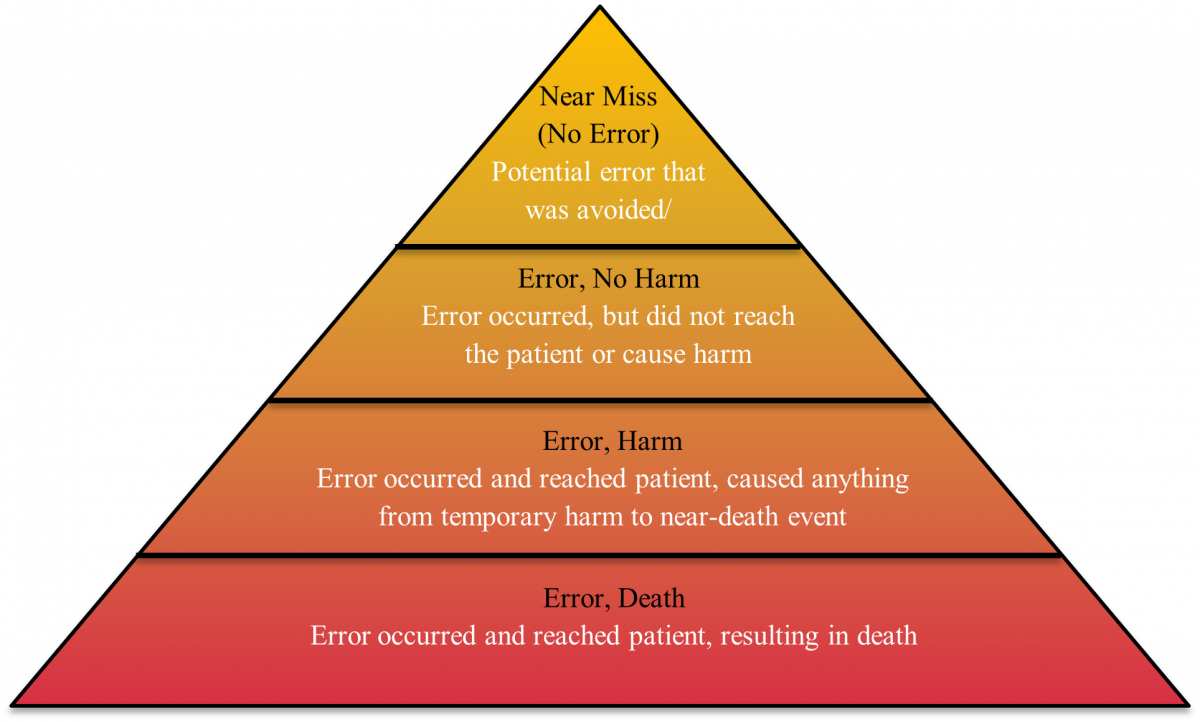

Most medication errors are preventable and can also be classified by the severity of their impact on the affected patient. Leading organizations, such as NCC MERP, have developed taxonomies to classify medication errors in more detail, including nine categories labeled A through I. These categories range from circumstances that have the capacity to cause error (Category A) to errors that result in patient death (Category I). While categories E through I describe varying degrees of harm to the patient, categories A through D involve situations with no patient harm. These classifications help institutions analyze trends and implement targeted interventions.5

Figure 1 displays NCC MERP’s medication error classifications with severity levels increasing from top to bottom.5

Figure 1. Medication Error Classification5

A patient comes in to pick up a prescription at Ray and Kai’s pharmacy and the line is out the door. As Kai retrieves the medication, she quickly confirms the patient’s last name and date of birth. Ray knows the patient and greets him; “Hey Charlie, how are the kids?” Kai then realized the prescription in hand was meant for a different patient by the name of Billy and was in the same bin. The correct medication is retrieved, and the patient safely receives what was actually prescribed, resulting in a near miss, rather than a full medication error.

Later, Ray and Kai sit down to reflect on what could have happened if the mistake hadn’t been caught in time. If the pharmacy dispensed the wrong medication and the patient noticed and brought it back before taking it, this would be an error, no harm situation. However, if the patient took the incorrect medication and experienced harmful adverse effects, it would result in an error, harm situation. In a more severe scenario, if the patient took the wrong medication and had an allergic reaction or other fatal outcome, it would be considered error, death. After discussion, Ray and Kai decide to speak to the staff about the importance of verifying patient information in full at every encounter. They relay a PRO TIP: employees can place prescriptions for patients with similar names in separate bins to avoid confusion.

Even the smallest and most routine tasks, such as verifying a patient’s identity, carry immense responsibility. Every action performed in a pharmacy setting has a direct impact on patient health. A moment of inattention or a skipped step can be the difference between preventing harm and causing irreversible consequences. That’s why it is crucial to approach every task, no matter how routine, with full attention and diligence

Beyond preventing individual mistakes, classifying and analyzing medication errors is a key to improving patient care on a larger scale. Recognizing and labeling these errors—whether they are near misses, errors with no harm, or more serious mistakes—provides valuable insight into when and where they happen. By identifying patterns, pharmacies can implement targeted safety measures to minimize risks.4,5

ANALYSE, DOCUMENT, PREVENT

Medication Error Rates

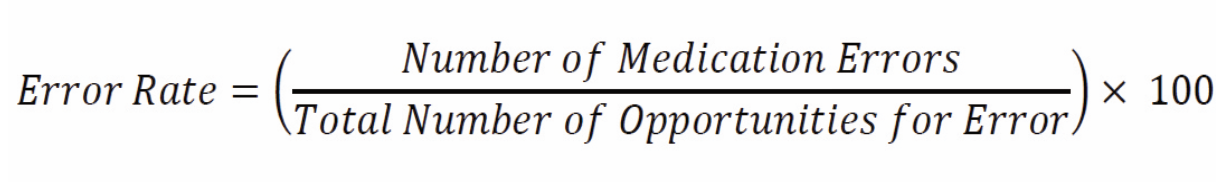

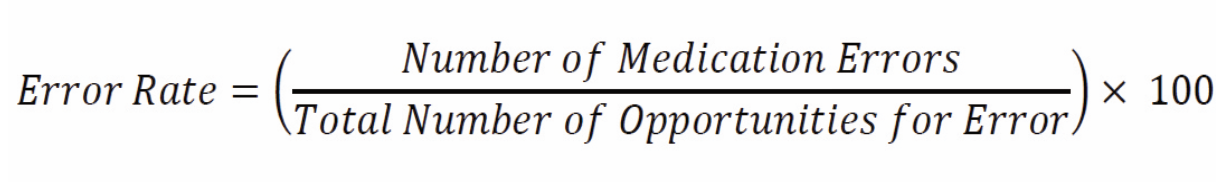

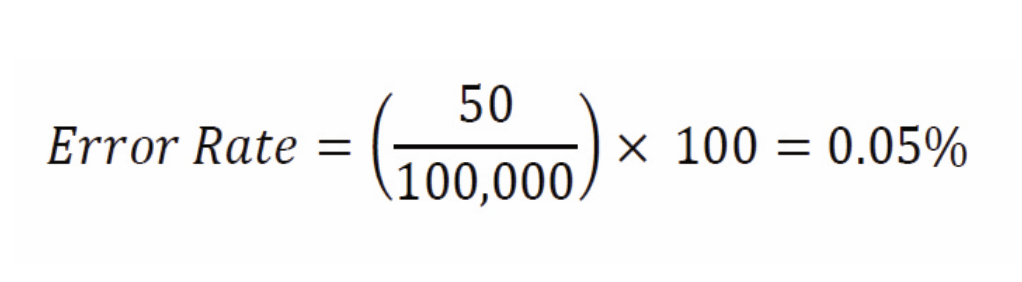

To identify and reduce medication errors effectively, individuals and institutions must track their occurrences systemically. One of the most effective ways to achieve this is by calculating the medication error rate, which provides valuable insight into areas requiring improvement.6 The formula for calculating the medication error rate is as follows:

<<ADD IMAGE>>

The numerator represents the total number of medication errors recorded during a given period, with each error event counted as one. The denominator consists of all medication orders or doses that were dispensed and administered.6 This formula applies across all pharmacy settings, including both community and hospital environments.

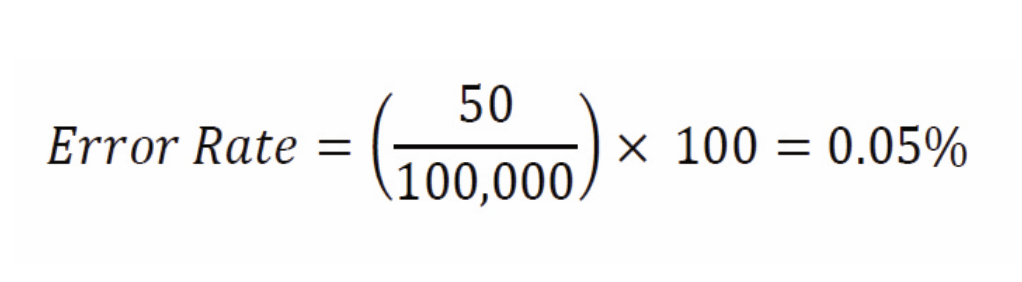

For example, a hospital pharmacy dispenses 100,000 doses in a month and identifies 50 medication errors in that month. What is the medication error rate?

Once calculated, error rates are a crucial tool for identifying trends and implementing targeted interventions. By analyzing the data, healthcare teams can pinpoint high-risk areas, set measurable goals, and put corrective measures into action to minimize errors. This proactive approach not only enhances patient safety; it also optimizes pharmacy workflow and overall efficiency.

The pharmacy where Ray and Kai work is accredited. During an accreditation audit, one of the surveyors asks Ray about their medication error rate. Ray is unable to answer. The surveyor pushes a little and asks Ray to provide copies of all incident reports regarding medication errors. Ray finds two or three in which the medication error was serious enough to attract attention from the clinical staff or the clinic's risk manager. When the surveyor explains how to calculate a medication error rate, Ray listens carefully. Needless to say, the surveyor noted the lack of documentation about medication errors as a deficit in the survey and indicated that she did not believe that they only had three medication errors in the past year. When Ray and Kai meet to plan corrective action, they realize that without good documentation, they cannot make this calculation.

To ensure accuracy and reliability, all pharmacy and healthcare organizations must foster a culture of transparency and promote non-punitive error reporting.6,7 Management must encourage staff to report errors without fear of retribution, allowing institutions to collect comprehensive data and develop effective mitigation strategies. Hospitals and community pharmacies can gain valuable insight into their performance by benchmarking their calculated error rates against institutions of similar size and complexity. Comparing rates with national standards or similar organizations helps ensure adherence to best practices and provides insight into additional potential interventions.7

Documenting Medication Errors

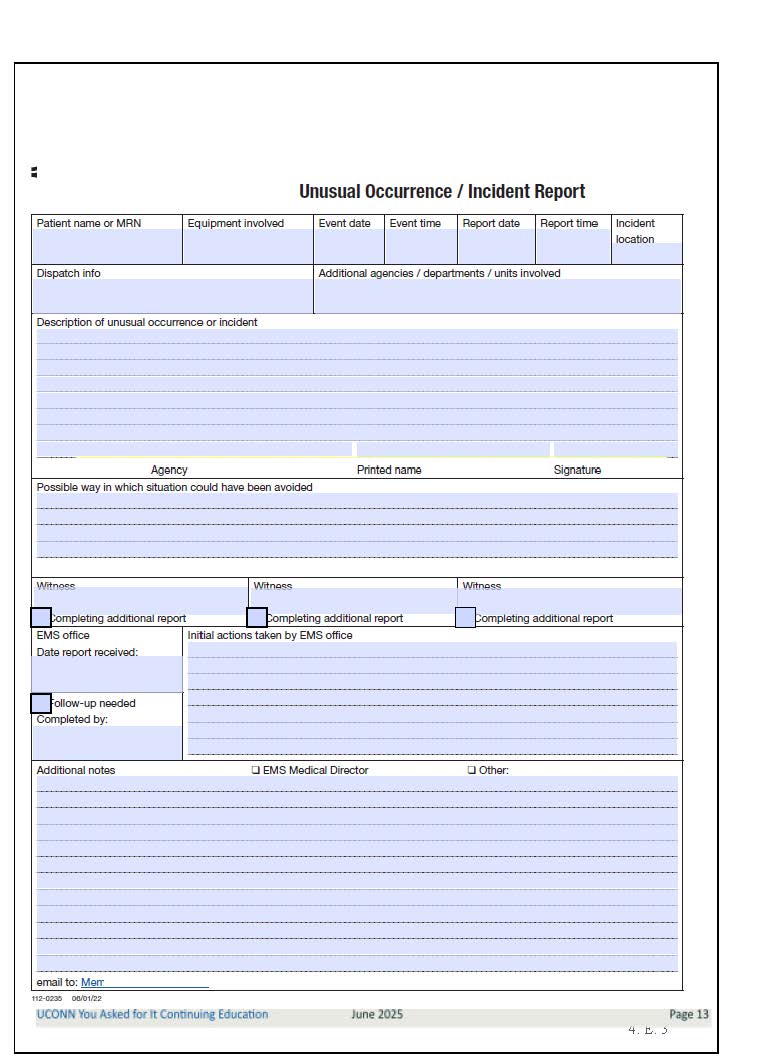

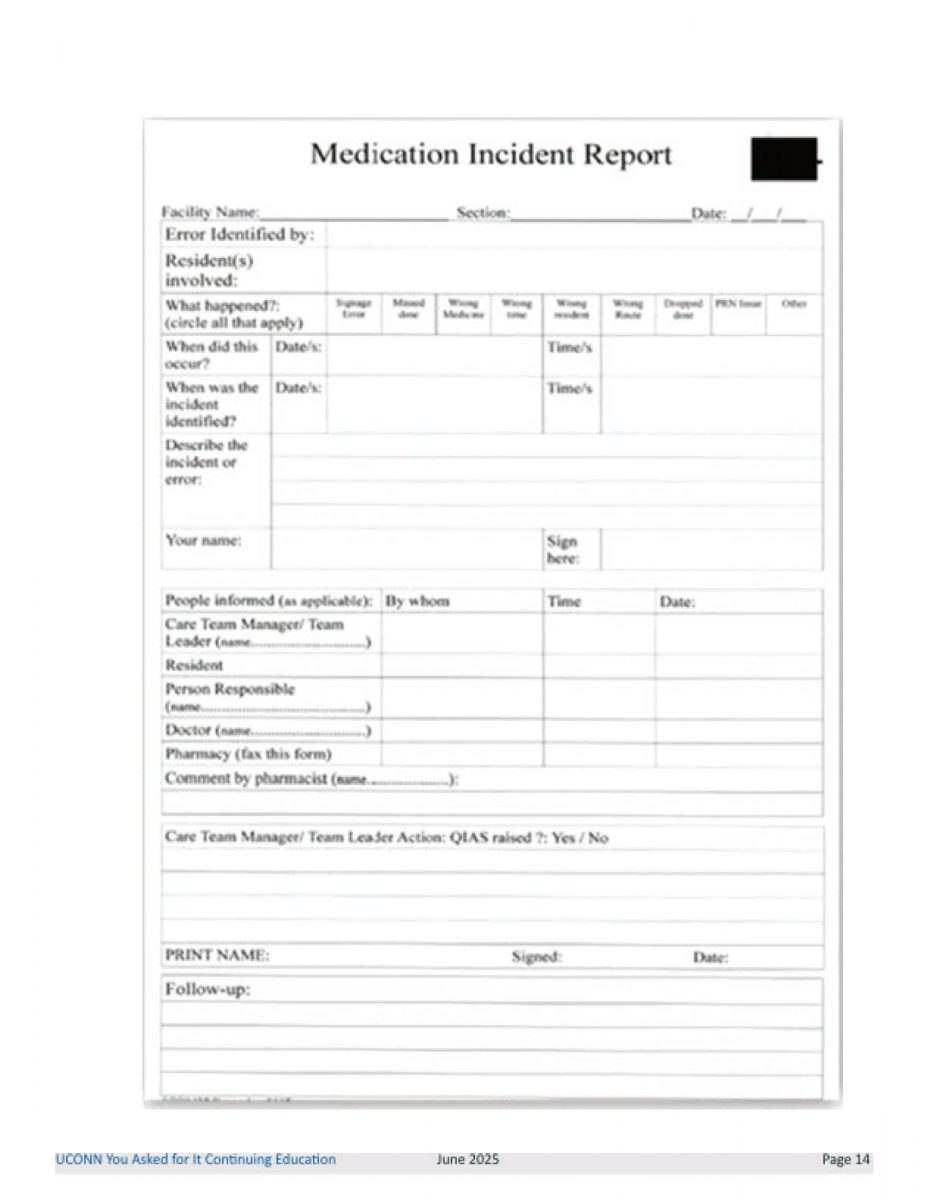

Pharmacists and technicians should know how to document and report incidents that occur in their pharmacy properly, usually following policies or procedures put in place by their institution and legal regulations. Unusual incident reports (UIRs) are a formal mechanism for documenting clinically significant medication errors and near misses.

Following identification of an incident and corrective patient measures, all relevant personnel should be notified and asked to record their recall of events. These reports should include key details such as who was involved, when and where the incident occurred, type of error, contributing factors, and corrective actions taken.8 To prevent recurrence of an incident or find a systemic issue leading to incidents, errors should regularly be recorded regardless of severity or whether it reached the patient or not. A PRO TIP is to maintain a list of errors that should be documented and keep unused UIRs in an accessible place (e.g., pinned on all desktops or stored in designated folders), encouraging staff to fill them out. These forms should be completed in full and a PRO TIP is to include instructions on what steps to take following the incident (i.e., read over and include any forgotten details, ensure all relevant staff is notified). Investigative staff should thoroughly gather data pertaining to the incident, including records, UIRs, patient notes, and physical items used in the event.9 Staff should establish a clear chronology of events to determine the root cause and prevent future occurrences.

Pharmacists and technicians should be well-versed in properly documenting and reporting incidents in their pharmacy, usually following institutional policies and legal regulations. UIRs serve as a formal mechanism for recording clinically significant errors and near misses. The following steps are necessary for proper documentation and reporting8-10:

- Identify and respond to the incident

- When an error or near miss occurs, prioritize patient safety by taking corrective actions and notify all relevant personnel, including leadership.

- Thoroughly document the incident

- UIRs should capture key details such as

- who was involved

- when and where the incident occurred

- type of error and contributing factors

- corrective actions taken and follow-up measures

- All involved personnel should document their recollection of events promptly to ensure accuracy.

- Encourage consistent reporting

- To prevent recurrences and identify systemic issues, all errors—regardless of patient impact severity—should be recorded.

- PROTIP: Maintain a list of errors that must be documented and keep unused UIRs easily accessible (i.e., pinned on desktops or stored in a designated folder) to encourage completion.

- Forms should be fully completed, and staff should review their entries for accuracy before submission.

- Investigate and analyze the incident

- Investigative staff should collect all relevant data, including UIRs, records, forms, and any physical items used in the event.

- Establish a clear chronology of events to determine the root cause and prevent future occurrences.

UIRs are considered Quality Improvement data in healthcare organizations, making them confidential and generally protected from disclosure under laws like the Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act.11 Organizations use these reports internally to enhance patient safety and do not share them with patients or lawyers. However, protection can vary based on state laws and institutional policies, so a PRO TIP for organizations would be to highlight their specific policies and require additional training and separate filings to ensure proper procedures to maintain confidentiality.

Individuals must report serious medication errors resulting in patients harm or regulatory violations to state boards of pharmacy and should also report them to accreditation agencies (e.g., Joint Commission) and the FDA through the MedWatch program.8 Pharmacy personnel is expected to know how and when to use institution-specific forms and to revise these to simplify and encourage the error reporting process.

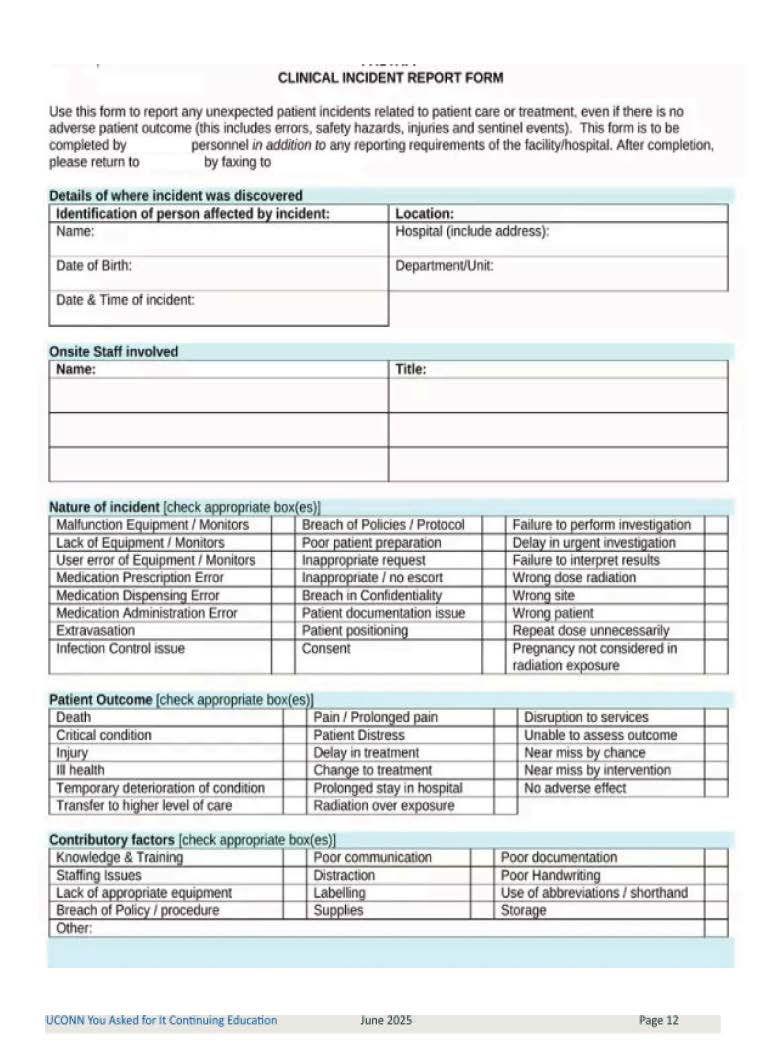

Ray and Kai are motivated to track medication errors better. When they dust off their stack of unused UIR forms, they realize that their forms are skeletal and their organization would benefit from a better tool. One of their technicians, Tara, volunteers to look at a number of different forms and identifies four. The staff chooses to “pilot” two, meaning they will document all medication errors that occur over the next three weeks on both forms, and then analyze the results. At the end of the pilot, they choose one form but realize that they need to tailor it to their practice. Tara also notes that they could automate the form and include a picture of the dosage forms that were involved.

Within three months, Ray and Kai realize from the pictures that a full 25% of their errors involve tablets that are white. Ray and Kai can share a PRO TIP with other organizations now. They create a whiteboard that lists most of their white tablets and the tablet markings. The technicians who handle inventory update the whiteboard when they change generics. Additionally, whenever Ray or Kai visually verify a prescription for a white tablet, they note the tablet marking on the prescription. In this way, they eliminate a good number of errors.

Institutions may have different methods for documenting unusual incidents, so it is essential that pharmacy staff know how to access and properly complete these forms. Keeping UIR forms up to date ensures they remain effective and relevant. Attached are three different incident report forms; review them carefully and identify their similarities and differences (see Appendix).12-14

Accurate medication error reporting is the underpinning of identifying risks and improving patient safety. However, traditional error-reporting systems often capture only a portion of actual incidents and do not usually account for adverse effects. This could be attributed to limitations in error-reporting, including but not limited to underreporting due to fear of punishment, time-consuming processes, and a lack of feedback and follow-up.15 Research suggests that the use of observation, when appropriate and feasible, could lead to more accurate detection of medication errors in practice.16,17 When applicable, institutions can use observation in combination with tracking error reports and greatly reduce the frequency of medication errors.

A strong culture of safety in pharmacy practice encourages transparent error reporting and non-punitive responses. Employees should feel comfortable reporting mistakes without fear of disciplinary action, as this fosters a learning environment rather than a blame culture. Encouraging reporting allows institutions to7,18

- identify error trends and implement preventative measures

- provide additional training where needed

- improve medication safety policies and procedures

All people in positions of authority should encourage pharmacy personnel to report medication errors to their institutions and to the FDA, ISMP, or NCC MERP if appropriate.19

System-Based Prevention Approaches

Healthcare institutions implement structured systems to enhance workflow efficiency and minimize medication errors. These systems provide standardized protocols, technological advancements, and communications strategies that help pharmacy personnel ensure safe and accurate medication dispensing and administration.

With advancements in technology, healthcare professionals frequently rely on automated systems to assist with medication safety. While these tools greatly reduce the potential for human error, they should be used to complement, not replace, pharmacist and technician expertise. Proper training and implementation of these tools are essential to their effectiveness. Key technologies that reduce medication errors include the following18,20,21:

- Barcode scanning as an additional verification step in the dispensing and administration process ensures that the correct drug, dose, and patient matches the prescription and manufacturer specifications.

- Computerized provider order entry (CPOE) and e-prescribing reduce errors by eliminating the risk of misinterpreting handwritten prescriptions. CPOE also alerts prescribers about potential drug interactions, allergies, and dosing errors before orders are processed.

- Automated dispensing cabinets, commonly used in hospitals, help regulate medication storage, access, and tracking to prevent unauthorized or incorrect dispensing.

To maximize these systems’ effectiveness, pharmacy staff must remain vigilant, ensuring that they do not blindly trust automation. As recommended by the ISMP, conducting manual double-checks judiciously, selective to certain high-risk tasks or medications, can further enhance patient safety.22

Familiarizing all staff with institutional standard operating procedures (SOPs) is essential for ensuring consistent and safe practice. These guidelines outline step-by-step procedures for specific pharmacy operations, reducing deviations that could lead to medication errors.23 When adhered to properly, SOPs standardize processes (minimizing variability and human error), provide clear instructions for handling high-alert medications, and outline best practices for prescription verification, dispensing, and patient counseling.21,23 For example, a hospital SOP may require two licensed healthcare professionals to verify chemotherapy doses independently before administration. In a community pharmacy, an SOP may require mandatory counseling for first-time prescriptions of high-risk medications, such as opioids or anticoagulants. Having SOPs and checklists readily accessible ensures that pharmacy personnel can reference best practices quickly when dealing with complex or high-risk situations.

SIDEBAR: A Word About CHECKLISTS

When checklists are numerous in quantity and poor in design, pharmacy staff may experience a sense of checklist fatigue, becoming overwhelmed and disengaged with completing them. This could lead to rushed or skipped steps, negatively impacting performance and patient safety. The following lists some strategies to avoid feeling desensitized to the repetitive nature of checklists22,24,25:

- Use checklists selectively by focusing on the most important or highest-risk tasks

- Improve the design to be clear, concise, and easy to follow

- Avoid unnecessary or redundant steps

- Regularly ensure the checklists are up-to-date and effective

- Address fatigue with staff and provide training and feedback on the importance of each step

PAUSE AND PONDER: When reviewing a prescription, what red flags should prompt you to double check with a prescriber, pharmacist, or colleague?

PHARMACY PRACTICE CONSIDERATIONS

Each pharmacy practice type has its own unique concerns and considerations with regard to medication error reporting.

Community Pharmacy

In a retail or clinic pharmacy setting, like the one in which Ray and Kai work, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians must exercise caution throughout the prescription filling process to prevent errors. These errors can be minor and initially go unnoticed, but can lead to serious adverse events, hospitalizations, or even fatalities if not promptly identified and addressed.26

The first stage of medication processing—receiving a prescription—creates a significant risk for errors. Whether prescriptions are transmitted electronically, by phone, or handwritten, pharmacy personnel may misread, misinterpret, or fail to recognize important details.27 Especially in high-volume settings, healthcare professionals should prioritize accuracy by seeking prescriber clarification when needed, rather than making assumptions or rushing through interpretation. Errors can also originate from prescribers, and pharmacy personnel should have a high index of suspicion that every prescription is incorrect. Calling to clarify questionable doses or frequencies ensures patient safety and may also prompt prescribers to recognize and correct unintended mistakes.26 All three errors that Ray and Kai documented had been serious enough to result in an ADE or ADR. When they looked back at these errors, they realized that for two of them, if they had questioned the patients or called the prescribers, the errors may have been avoided entirely.

Common errors that pharmacists and technicians should be vigilant about in community pharmacy include1,3,27,28

- Misinterpreting abbreviations and symbols: Sloppy abbreviations and symbols can lead to dangerous dosing errors. Table 2 summarizes the Joint Commission’s “DO NOT USE” list of abbreviations that should be displayed in pharmacies.

- LASA medications: Medications with similar names can be easily confused if not carefully verified.

- Incorrect dosing and strength selection: Errors can occur by selecting the wrong strength of a medication or miscalculating pediatric or weight-based doses.

Table 2. The Joint Commission’s “DO NOT USE” List28

| Do Not Use |

Potential Problem |

Use Instead |

| U, u |

Mistaken for “0” (zero), the number “4” (four) or “cc” |

Write “unit |

| IU |

Mistaken for IV (intravenous) or the number 10 (ten) |

Write “International Unit” |

| Q.D., QD, q.d., qd

Q.O.D., QOD, q.o.d., qod |

Mistaken for each other

Period after the Q mistaken for “I” and the “O” mistaken for “I” |

Write “daily”

Write “every other day” |

| Trailing zero (X.0 mg) *

Lack of leading zero (.X mg) |

Decimal point is missed |

Write X mg

Write 0.X mg |

| MS

MSO4 and MgSO4 |

Can mean morphine sulfate or magnesium sulfate

Confused for one another |

Write “morphine sulfate”

Write “magnesium sulfate” |

*Exception: A trailing zero is only allowed when necessary to indicate the exact level of precision, such as in laboratory results, imaging studies that report lesion sizes, or catheter/tube sizes. It may not be used in medication orders or other medication-related documentation.

Maintaining readily accessible reference lists can help pharmacy personnel cross-check potential medication errors before contacting prescribers. The ISMP has identified numerous LASA pairs that contribute to medication errors and has created lists of commonly confused abbreviations and symbols.29 Additionally, using TALL Man lettering (e.g., capitalizing part of a drug's name in upper case letters to differentiate similar drug names like hydrALAzine vs hydrOXYzine) when documenting or labeling LASA medications can minimize confusion.29

In the hypothetical pharmacy, Ray notes that one of the technicians consistently fills prescriptions for dipyridamole with diphenhydramine. He has pointed this problem out to the technician several times and asked the technician to find the correct medication, but the problem continues. After learning about TALL Man lettering, he realizes that their computer system does not use this simple but useful intervention. He contacts the programmers and asks if they can make the changes, providing the ISMP's list of drugs for which this intervention could prevent many errors. A PRO TIP here is to ask the technician to use a highlighter to highlight the part of the drug name that follows "DIP-" on all drugs that begin with these three letters before filling prescriptions.

Errors often arise during the later stages of prescription processing, including data entry, assembly, and pharmacist verification. Pharmacy personnel may rely too heavily on the auto-populated fields in electronic prescribing systems (e.g., McKesson, PioneerRx), assuming the information is correct without double-checking key details. This could lead to incorrect medication strengths, frequency, or refill quantities, ultimately causing billing issues or improper medication dispensing.27,20

Dispensing the wrong formulation can occur if pharmacy staff select similar-looking bottles. Barcode scanning technology can help reduce assembly errors by ensuring use of the correct product. Pharmacists must physically inspect medications rather than relying solely on electronic systems. Pharmacy staff should attach medication guides, auxiliary labels, and other patient education materials as necessary. Pharmacy professionals must recognize that technology is a tool, not a replacement for human oversight. Systems may have glitches or auto-fill errors, and staff should remain vigilant to manually verify accuracy when needed. 20

Over the few weeks after the accreditation survey, Ray and Kai see a number of minor medication errors in the pharmacy. During a counseling session, Kai learns that one patient has been taking a diuretic but has not been increasing the amount of potassium in her diet. The patient reports cramping and nausea. Kai realizes that the pharmacy staff stopped using colorful auxiliary labels, assuming that the key counseling points are covered in the multi-page handout that the computer prints with each prescription. Unfortunately, many patients simply throw that multi-page handout into the recycle bin (as did this patient). Kai realizes that using auxiliary labels is an opportunity to improve counseling and to increase the likelihood that patients will take medications correctly.

The final step in the prescription process—dispensing the medication to the patient—requires uninterrupted attention to detail. Staff often overlook or rush this step in busy retail pharmacies, especially under pressure from patients who may be in a hurry. Patients who are eager to leave or have pressing time constraints may create an environment where staff feel rushed to complete the transaction quickly, potentially compromising safety. The Joint Commission requires two patient identifiers before dispensing a medication (e.g., full name and date of birth) to prevent mix-ups.26 Failing to confirm the patient’s identity may result in a patient receiving the wrong prescription, leading to serious consequences.

While not all patients will ask for counseling, it is the pharmacy staff’s responsibility to offer counseling proactively, especially in critical situations. Pharmacy staff must remain alert to identify potential medication errors and recognize when pharmacist intervention is necessary. Pharmacy technicians are essential to this process. In our hypothetical pharmacy, Ray and Kai realize that the way that they've been dealing with medication errors isn't conducive to ideal teamwork. Further, they realize that they need to engage their technician support team so the pharmacist becomes involved in the process earlier when technicians see red flags.

Common errors that require technician awareness and referral to the pharmacist include2,4,20

- misuse or incorrect administration

- first-time prescriptions, dose changes, or class switches

- high-risk medications or drug interactions

- duplicate therapy or overlapping prescriptions

By actively engaging in patient education and ensuring clear communication at the point of dispensing, pharmacy professionals can significantly reduce medication errors and enhance patient safety. A PRO TIP comes from the Indian Health Service where pharmacy staff take a few minutes to remove medication from the bag, read the drug name, open the bottle, shake a few dosage units into the cap, and show it to the patient. Patients may identify medications that look different than they remember, which may signal a change in generic supplier or may identify an error. Although this process sounds time consuming, it actually takes just a few seconds for each bottle, and it prevents adverse outcomes in many cases.

Hospital Pharmacy

Hospital pharmacists and pharmacy technicians have serious responsibilities in ensuring safe medication use among high-risk patient populations. Like patients seen in the community, hospitalized patients often have complex conditions, multiple comorbidities, and require high-alert medications. But any event that precipitates hospitalization increases vulnerability to medication-related adverse events.21 Learners should note that many of these interventions apply in community centers as well.

Similar to retail or clinic pharmacy, miscommunication between prescribers and pharmacy personnel remains a leading cause of medication errors in hospitals. Healthcare providers can reduce errors through effective communication, verification, and collaboration. Regularly confirming prescription details and clarifying discrepancies helps prevent errors before they reach patients. Pharmacy staff need to establish trust and employ open communication with prescribers to ensure patient safety in hospitals. A breakdown in interprofessional relationships can lead to medication errors, such as18,21

- incorrect medication selection due to misinterpreted verbal or written orders

- dosing errors, particularly in pediatric or renally impaired patients, when key patient information is not communicated

- failure to adjust medications in response to changing renal or hepatic function, leading to toxicity or subtherapeutic dosing

- missed allergy documentation, resulting in patients receiving medications that trigger adverse reactions

By fostering a culture of open dialogue and verification, hospital pharmacy teams can minimize preventable errors and ensure optimal patient care.

Consider a hospital pharmacy that employs nine pharmacists on three shifts, with a staffing ratio of one pharmacist to two technicians throughout the entire 24 hours. This pharmacy does a better job of documenting medication errors on unusual incident reports, but considerable room for improvement remains. Lisa is the pharmacist who works closely with the Performance and Quality Improvement (QPI) Department. Her liaison in QPI notifies Lisa that of the 46 medication errors reported in the last quarter, eight were associated with orders from a hospitalist, Dr. Backoff, who rotates shifts. The underlying cause seems to be miscommunication. Dr. Backoff is well known for his offensive behaviors; he humiliates people who ask questions, intimidates coworkers using insults or repeatedly bringing up past errors, excludes staff from opportunities to participate, and is generally so critical that people avoid him.30

When staff call Dr. Backoff, he often fails to return the call. Over time, the situation has escalated to the point where staff are afraid to pick up the phone and call him when problems occur. As Lisa works with her QPI liaison, they realize that their workplace has no comprehensive policies and procedures targeting workplace bullying. Without clear guidelines and protocols, people who are targeted by bullies may feel powerless and unwilling to work with their bully.31 A PRO TIP is that this organization needs to develop training to address bullying, and Lisa and the QPI liaison need to speak to Dr. Backoff's supervisor immediately. The supervisor can refer Dr. Backoff to employee assistance program or implement corrective and disciplinary action.

Certain medications require heightened safety precautions due to their potential for severe patient harm if misused. The ISMP has a list of high-alert medications that require extra safeguards in hospital settings. An example of these are anticoagulants; even small dosing mistakes could lead to severe bleeding or thrombosis (clotting).32 Due to the serious risks associated with high-alert medications, pharmacy staff pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should double-check and arrange independent verification consistently.21

Medication errors frequently occur during transitions of care, including hospital admission, transfers to other facilities (e.g., long-term care, rehabilitation), and discharge to home. These errors can result in unintentional medication discontinuation, dose and frequency errors, or discharge medication miscommunication, significantly increasing patients’ risk of harm.33 One of the most significant risks during transitions of care is unintentional medication discontinuation (mistakenly stopping an essential chronic medication). Dose and frequency discrepancies and miscommunications about discharge medications further increase the risk of ADEs post-hospitalization.34

To prevent these errors proactively, hospital pharmacists and pharmacy technicians should21,33

- conduct a thorough medication reconciliation at the time of admission, ensuring all home medications are accurately documented

- maintain clear, updated medication lists through each stage of hospitalization

- collaborate to ensure patients and caregivers receive comprehensive discharge counseling, with the technician reminding or prompting pharmacists if this step is missed, and reinforcing medication changes adherence instructions

Lisa’s hospital has a structured transitions of care program. They hire pharmacy students to conduct medication reconciliation under a pharmacist’s supervision. Before pharmacy students can conduct medication reconciliation, they complete a comprehensive training program. Regardless, errors on the medication list still slip through.

Lisa's hospital is not alone with this problem. Many hospitals find that errors occur even after medication reconciliation. A 2024 study of the medication reconciliation process and related medication errors indicates that these processes are “very heterogeneous,” meaning that in some areas, medication reconciliation was very good and in others, not so much.35 They found that error rates were unexpectedly high in some areas. This study looked at 929 prescriptions written for 182 patients. In 91% of cases, the reconciler had not specified the drug form. About 72% of medication administration errors pursuant to a faulty medication reconciliation exercise resulted in patients receiving the wrong release dose formulation (i.e., immediate release as opposed to extended release). The researchers indicated that medication error rates did not improve significantly over the period before they conducted routine medication reconciliation.35

Lisa has heard coworkers talk about medication reconciliation as a useless process and seeing them roll their eyes when they look at a medication reconciliation report that has obvious errors. In the past, pharmacy staff did not consider a mistake on a medication reconciliation list to be a medication error. However, when a serious error slips through, Lisa’s QPI liaison suggests that they began tracking such errors on unusual incident reports. A PRO TIP here is to track errors in medication reconciliation and try to identify the areas where errors are most likely to occur in the medication reconciliation process. At this hospital, Lisa and the QPI liaison were able to confirm that they also had a problem with identification of the correct formulation. Over the following months, they were able to improve by using additional training and revising their medication reconciliation form to force technicians to ask about the formulation or to see the bottle.

PAUSE AND PONDER: Can you think of any processes or policies in your workplace that can be improved to enhance patient safety?

Pharmacist and Technician Responsibilities

Pharmacy professionals have a responsibility to actively communicate with their colleagues and other healthcare providers to prevent errors. Effective collaboration within the healthcare team ensures safe medication practices by18

- clarifying unclear or incomplete prescriptions before dispensing

- confirming appropriate dosing adjustments for renal or hepatic impairment

- coordinating medication reconciliation during transitions of care to prevent omissions or duplications

Management needs to empower pharmacists and pharmacy technicians to voice concerns regarding potential medication errors. Addressing these concerns professionally and respectfully fosters a culture of teamwork and patient safety.

A key responsibility of pharmacy professionals is to provide clear, understandable medication counseling to patients. However, it is unrealistic to expect that staff can counsel all patients on every detail of their prescription. Instead, pharmacists should prioritize the most critical points, especially on new prescriptions, including36

- dosing instructions and adherence importance

- common and serious adverse effects

- drug interactions and contraindications

- proper storage and administration techniques

One effective counseling strategy is the teach-back method, where patients repeat the pharmacist’s instructions back in their own words. This ensures patients fully understand how to use their medication correctly. For example, when dispensing doxycycline, instead of simply stating “Take this with a full glass of water,” a pharmacist using the teach-back method would ask one simple question after explaining how to take the doxycycline: “Can you explain to me how you will take this medication to avoid stomach irritation? I need to be sure I covered everything.”18,21,26

When a serious medication error occurs, it is crucial to investigate the underlying causes to prevent future occurrences. Root-cause analysis (RCA) is a structured problem-solving method used to analyze errors after they have happened—including what, how, and why it happened—and can help determine what lessons could be learned and how to reduce the risk of recurrence and make care safer.3,21 For example, if a retail pharmacy dispenses the wrong insulin type and a patient is subsequently hospitalized, an RCA might reveal that the error stemmed from look-alike packaging and a lack of independent verification.

Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) is a proactive approach to medication safety, identifying potential failures before they occur. By evaluating processes and pinpointing high-risk areas, institutions can implement safeguards to prevent errors before they reach patients.21 For instance, before introducing a new automated dispensing cabinet, an FMEA could help identify potential failure points, such as medication selection due to user interface design, allowing for preventive modifications.

CONCLUSION

Patient safety is a fundamental pillar in pharmacy practice, and reducing medication errors requires a proactive, systematic approach. Errors can occur at any stage of the medication use process, from receiving and interpreting prescriptions to dispensing and patient counseling. Recognizing common errors—such as abbreviations, LASA drugs, incorrect dosing, and transcription mistakes—helps pharmacy professionals to implement safeguards that prevent harm.