Learning Objectives

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacist preceptors will be able to

- DEFINE types of learning disabilities that preceptors are likely to encounter

- LIST the information the school of pharmacy should provide to preceptors

- IDENTIFY accommodation that are appropriate for specific students

- DESCRIBE reasonable accommodation in experiential education

Release Date: December 10, 2023

Expiration Date: December 10, 2026

Course Fee

Pharmacists: $5

UConn Faculty & Adjuncts: FREE

There is no grant funding for this CE activity

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-23-059-H04-P

Session Code

Pharmacist: 23PC59-ACA37

Accreditation Hours

1.0 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-23-059-H04-P will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Jennifer Luciano, PharmD

Director, Office of Experiential Education; Associate Clinical Professor

UConn School of Pharmacy

Storrs, CT

Neha Patel

2025 PharmD Candidate

UConn School of Pharmacy

Storrs, CT

Jeannette Y. Wick, RPh, MBA, FASCP

Director, Office of Pharmacy Professional Development

UConn School of Pharmacy

Storrs, CT

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Jeannette Wick, Neha Patel, and Jennifer Luciano do not have any relationships with ineligible companies

ABSTRACT

From time to time, preceptors need to address the needs of students who have disabilities, be they visible or invisible. Students’ disabilities may include chronic diseases, physical limitations, or difficulty with processing information. This continuing education activity introduces various types of disabilities that preceptors may encounter and suggests a stepwise process to develop accommodation plans. It discusses information that preceptors will need or want to have on hand, and potential sources to obtain the information. It also describes the various stakeholders and the accommodation process and the potential benefits for the entire workplace.

CONTENT

Content

INTRODUCTION

Some pharmacy students have visible or invisible disabilities that require accommodation (a change or adaptation to adjust a situation to meet the student’s unique needs). Anecdotally, faculty at the University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy report that between 5% and 12% of students in a typical class in the last 10 years need accommodation. In terms of physical disabilities, institutions of higher learning have almost always built or altered existing buildings to accommodate students with disabilities with ramps, elevators, wide doors, and similar structural changes. Preceptors who work in larger organizations may have support teams that address or have already addressed physical disabilities. Those who work in smaller organizations or older buildings may be intimidated by the need to accommodate but will find that the law requires “reasonable” accommodation.

Pharmacy preceptors are more likely to encounter students who have chronic disease (e.g., asthma, autoimmune syndromes, diabetes, etc.) or learning disabilities, including those who are neurodivergent (the SIDEBAR explains the concept of neurodiversity). While taking classes, pharmacy schools often (and are legally required to) provide accommodation for students with learning disabilities (see Table 1). They may provide double time or access to a quiet room during exams, permission to take breaks during class, or notetakers to help them depending on the disability type. Students with learning disabilities acquire, organize, retain, comprehend, or use verbal or nonverbal information differently than others. They have impaired perception, thinking, remembering, or learning processes.1

Table 1. Types of Learning Disabilities1-7

| Learning disability | Description |

| Anxiety disorder | Anxiety that does not go away and can worsen over time. Symptoms can interfere with daily activities such as job performance, schoolwork, and relationships. Subtypes of anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and various phobia-related disorders. |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | Causes an ongoing pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity that interferes with functioning and/or development.

|

| Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) | A neurologic and developmental disorder that affects how people interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave. Autism is known as a “spectrum” disorder because its wide variation in presentation and symptom severity.

People with ASD often have: · Difficulty with communication and interaction with other people · Restricted interests and repetitive behaviors · Symptoms that affect their ability to function in school, work, and other areas of life |

| Dysgraphia | A neurological disorder characterized by writing disabilities that appear as distorted or incorrect writing (inappropriately sized and spaced letters, or wrong or misspelled words despite focused instruction). |

| Dyscalculia | Causes consistent failure to achieve in mathematics marked by difficulties with counting, working memory, visualization; visuospatial, directional, and sequential perception and processing; retrieval of learned facts and procedures; quantitative reasoning speed; motor sequencing; perception of time; and the accurate interpretation and representation of numbers when reading, copying, writing, reasoning, speaking, and recalling. |

| Dyslexia | Impairs a person’s ability to read. Although varies by individual, common characteristics include difficulty with

|

SIDEBAR: Emerging Terminology and Necessary Understanding: Neurodiversity8-11

Neurodiversity refers to the diversity of all people, but is often used in the context of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), neurological or developmental conditions, and learning disabilities. It is neither a medical term nor a diagnosis; it’s a descriptor used to replace the tendency to think of behaviors as normal or abnormal or to marginalize certain people based on their behaviors. When thinking about neurodiversity, it’s critical to remember that there is no one right way of thinking, learning, and behaving, and all differences are not necessarily deficits. Neurodiversity is not preventable, treatable, or curable. It’s the result of normal variation in the human genome. The term is used to promote equity and social justice for people who are members of a neurologic minority.

Students who are neurodivergent experience and interact with the world around them in many different ways. Common characteristics among students who are neurodivergent include eye contact, facial expressions, and body language that are different than many other people’s.

Students may or may not disclose (or even know) they are neurodivergent. When students do, it is important for preceptors to acknowledge neurodiversity and ask directly about a person’s preferred communication style and accommodations, many of which are described in the text of this continuing education activity. Many of the accommodations for people who are neurodiverse also help other students and employees who do not fall into neurologic minority categories, including

- Offering or allowing individuals to make small adjustments to the workspace

- Avoiding sarcasm, idioms, euphemisms, and implications

- Providing concise instructions

- Posting information about due dates and meetings as far in advance as possible

- Treating all people with respect

Preceptors should foster environments that are conductive to neurodiversity, and to recognize and emphasize each person’s individual strengths and talents while also providing support for their differences and needs. It’s also helpful to know that many large companies are now adjusting their hiring processes to attract people who are neurodivergent. They’ve found that although some people have trouble navigating the hiring process, their unique abilities are valuable, increase the company’s productivity, and often lead to remarkable product and process improvements.

This continuing education activity is designed to help preceptors who encounter pharmacy students with disabilities develop workable plans. Preceptors should start by acknowledging a critical fact: accommodation isn’t special treatment. Accommodation levels the playing field so student pharmacists (and employees) can learn and do their best work.

PAUSE AND PONDER: You’re a preceptor for your state university. In April, the experiential education office notifies that you have one student per month from June through April. Shortly after, a staff member from the experiential education office calls and tells you that the student scheduled for August needs accommodation. What should you expect going forward, and what is the best time to plan?

Providing Reasonable Accommodation

Institutions of higher learning usually have entire departments that develop policies, document the student’s type and degree of disability, and develop student-specific accommodation plans. When students who have disabilities go on clinical rotations, rotation sites may have no processes or policies to provide the same accommodation. Preceptors may not know how to cater to their needs. Often, practice sites need only to make minor adjustments to their environments, policies, and procedures. Once the organization makes the changes, the policies will be ready for future students! A PRO TIP is that an astute student who has disabilities may be willing to help edit and adjust policies; this insight can be valuable. However, the student may not want to help as this can be an added burden that other students don’t have.

Five basic principles help schools ensure that clinical rotation sites provide reasonable accommodation for students on clinical rotations1,11,12:

- Before going on rotation, it is critical for the school to document the student’s disability with a reliable diagnosis. The school’s department for students with disabilities usually does this.

- All parties will need to work together to identify elements of the student’s disability that would cloud the preceptor’s ability to assess the student’s competence. Any accommodation should mitigate those elements.

- Preceptors should work with the school to develop accommodation tailored to the specific rotation site and tasks to be accomplished at that site.

- Three hundred sixty-degree communication is essential. Preceptors, students, school and rotation site administration, and disability service staff must collaborate and communicate.

- Throughout the whole process, all parties must protect the student’s privacy.

Students with disabilities are subject to a great deal of stigma not only from the outside world but also from preceptors. Ideally, schools should match these students with rotation sites and preceptors with prior experience accommodating students with disabilities.13 However, this may not always be possible. In ideal situations, preceptors are sympathetic and the relationship between the student and preceptor is open, non-judgmental, friendly, and relaxed. These characteristics set the stage for students to disclose their learning needs without fear of discrimination.14

The school, however, must identify sites and preceptors based on the student’s accommodation needs without disclosing student-specific accommodation descriptions. Open and honest communication between students, the experiential education team, and representative(s) of the school’s disabilities office before they develop the rotation schedule can prevent problems later.13 Once the school confirms the student’s sites, it can share very basic student-specific details with the preceptor but only the student can share specific health information.1 In other words, the school can communicate the accommodation the student needs, but not the underlying diagnosis; that is private and only the student may disclose it.

A challenge for students with physical disabilities is needing accommodation through multiple sites, which requires significant coordination and planning. A solution is providing multiple rotations at a single site where accommodation is available. When this solution is available, students can acclimate once.13 This can provide the best possible experience for the student, providing a level of comfort in the environment; conversely, this solution may force disabled students to stay at one site while their peers rotate from site to site and experience different healthcare teams. In institutions without pre-existing policies, schools would benefit by working with preceptors and the sites to develop guidelines for accommodating students. For students with physical disabilities, guidelines should address different types of mobility devices, physical dimensions of hospital facilities, safety requirements of the pharmacies, and access to particular areas.13 The preceptor should do this before the student begins working at the site. It would be unfortunate if a student arrived at a site only to find it was inaccessible.

Step-by-Step to Accommodation

Using a stepwise approach on site helps preceptors ensure that they provide reasonable accommodation to students.

- Raising awareness among the clinical team regarding disabilities, accommodation, and inclusive learning environments is a prudent first step. The team is able to do this by reviewing the literature, laws, and regulations. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Titles I, II, and III and the Rehabilitation Act (see Table 2) are the constellation of laws that prohibit discrimination and govern accommodation in pharmacy experiential education.15 Individual states may also have additional laws that protect disabled students.

Table 2. Federal Laws and Regulations that Protect Students with Disabilties15

| Law/regulation | Description |

| Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) | |

| Title 1: Employment | · Prohibits discrimination in recruitment, hiring, promotions, training, pay, social activities, and other privileges of employment.

· Restricts questions that can be asked about an applicant’s disability before a job offer is made · Requires that employers make reasonable accommodation for known physical or mental limitations of otherwise qualified individuals with disabilities, unless it results in undue hardship.

|

| Title II: Public sector | · Requires state and local governments to give people with disabilities an equal opportunity to benefit from their programs, services, and activities

· Requires reasonable modifications to policies, practices, and procedures where necessary to avoid discrimination, unless doing so would fundamentally alter the nature of their service · Does not require actions that would result in undue financial and administrative burdens · Indicates governmental agencies must communicate effectively |

| Title III: Private sector | · Explains public accommodation in businesses and nonprofits must not discriminate, exclude, segregate, or provide unequal treatment

· Requires businesses and nonprofits to make reasonable modifications to polices, practices and procedures and communicate effectively with people with hearing, vision, or speech disabilities · Requires employers to remove barriers and meet other access requirements. |

| Rehabilitation Act of 1973 | |

| Section 504 | Prohibits programs or activities that receive federal funding from discriminating against disabled people. |

One area that all employers and employees need to understand is that accommodation can include variations on the workspace or equipment needed to complete various tasks, how work is assigned and communicated, the specific tasks, and the time and place that the work is done.16

- Establishing essential learning activities and outcomes for students helps all students, not just those with learning or physical disabilities. This means specifying essential functions, minimum competencies, expectations, and procedures that all students must be able to perform by the end of the rotation.15 Preceptors should note that accommodating a student’s needs does not mean lowering expectations.1 A PRO TIP here is that sometimes a student can meet the expectation with only small changes in the preceptor’s style. For students who have information processing issues, asking questions and then pausing for five seconds to allow the student to answer is better than rapid fire questions.1 (This is actually an approach that all preceptors and teachers need to use more in all situations. Pausing benefits everyone, including people who are not native English speakers.)

- The rotation site should make reasonable accommodation based on a reliable diagnosis that the student has documented via the school’s office of student disabilities. The pharmacy school’s office will also provide documentation of the requested accommodation to preceptors; students who have disabilities should not make the requests to preceptors on their own; they may, however, provide the accommodation letter and any information they want to share with the preceptor and copy the school’s director of experiential education if that is the school’s policy. One area that can be difficult for preceptors is the student’s healthcare appointments.1 A PRO TIP is to ask the student at the beginning of the rotation if you need to be aware of any scheduled appointments. Preceptors should also be very clear that the student must notify them of unanticipated appointments as soon as possible (or even before they call to schedule the appointment). If students miss time at rotations, they are responsible for making up the time.

Documenting and discussing reasonable accommodation with the individual student who has a disability may be an uncomfortable or unfamiliar task for preceptors but will avoid problems later. Preceptors should meet with students to discuss exactly what they need in relation to their experiential outcomes (using the aforementioned list of specifying essential functions, minimum competencies, expectations, and procedures), asking questions such as1,15

- What limitations do you anticipate experiencing on the rotation?

- What tasks will you find problematic?

- What have you done in the past to reduce or eliminate these limitations?

- Do you anticipate needing us to make any modifications while you are here?

- What will you do if you encounter an unanticipated obstacle?

Here’s another PRO TIP: Knowing a few ways to accommodate disabilities will help preceptors help the student. For example, a student who has severe anxiety will find many rotations difficult and threatening. A preceptor can suggest that the student observe or “preview” activities before requiring interaction, especially if the site is fast-paced or chaotic. Allowing the student to arrive early may also help. Students who are challenged organizationally may benefit from one (not multiple) outline of what to expect every day.1

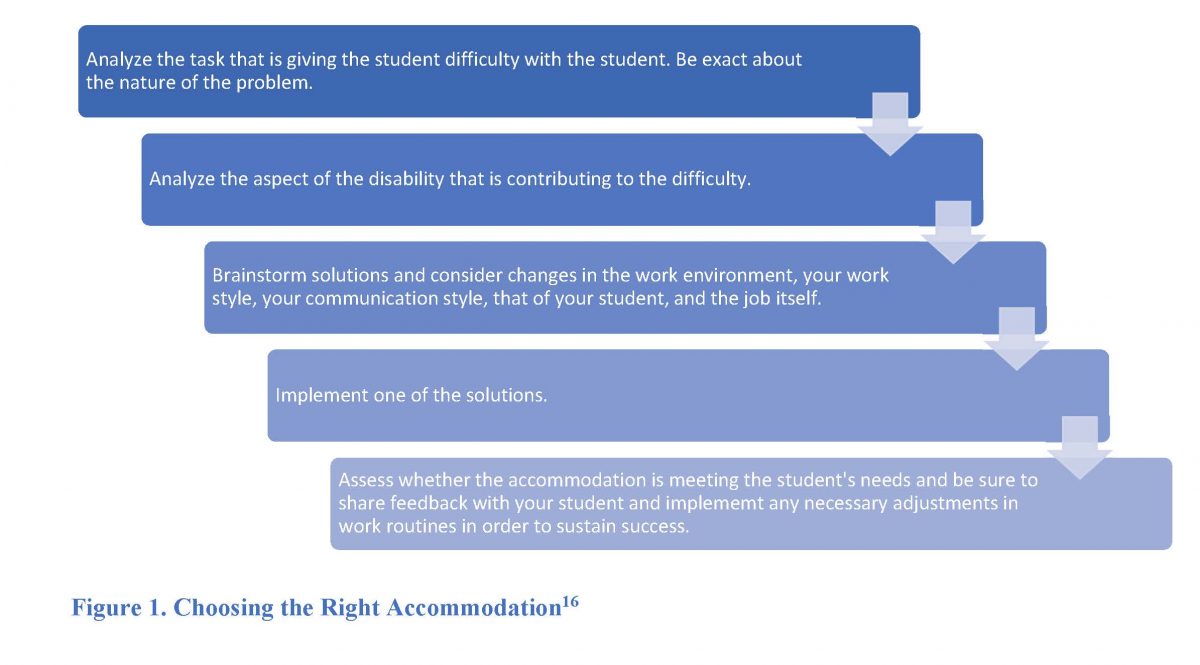

- The student should self-assess and document how the disability affects each general competency and how accommodation could mitigate each concern.1 Figure 1 describes the process of preceptors choosing accommodation.

The preceptor and student should develop an accommodation plan together and document it in writing. An ideal plan would list the intervention or accommodation and how it supports the student, those involved in creating the accommodation, and the parties responsible for any financial costs (discussed below). 11 For example, in a pharmacy setting where a great deal of business is conducted over the phone using headphones, a student who has difficulty hearing may need a phone amplifier. If the student wears hearing aids, headphones may interfere with her ability to hear. The plan should also include specific days/times for periodic check-ins so the student and preceptor can assess whether the intervention/accommodation meets the students’ needs and is still reasonable for the site.11

A PRO TIP for preceptors is to stay abreast of technology changes.16 If students have difficulty reading or writing—these are students with dyslexia or dysgraphia—many programs now have read-aloud or voice-to-text programs that are remarkably accurate. Some calculators will talk. Encourage students to use them. Asking students to listen to their work using a read-aloud program will also help them catch errors.

PAUSE AND PONDER: You meet with your new APPE student and learn that he has serious visual impairment. He indicates he needs to use assistive devices (supplemental lighting, a magnifier). How would you initiate a discussion about who will secure these devices?

The last step, which overlaps with the previous steps to some extent, is providing reasonable accommodation. Readers may read the term “reasonable accommodation” and wonder what is considered reasonable. Accommodation should not pose an undue financial or administrative hardship to the practice site.15 The law would not consider an accommodation reasonable if it decreased quality or posed safety issues to patients or imposed undue financial or administrative burden on the institution. It would also be unreasonable to change curricular elements or alter course objectives substantially. Preceptors might reach out to the school’s experiential education office who can contact the university’s legal department to determine whether a specific accommodation is reasonable. Or, preceptors can contact their own legal representatives. Preceptors and students need to communicate openly and honestly to determine reasonable accommodation together. Table 3 describes some examples of reasonable accommodation.

Table 3. Examples of Reasonable Accommodation in Clinical Experiential Learning8,15-17

| Student Limitation | Accommodation |

| Anxiety | · Embrace the learning experience and don’t be too hard on students when they make an error. Provide feedback and guidance for them to improve.

· Plan the days and weeks, setting achievable goals, and prioritizing tasks. · Offer counseling services and other resources to support the student. |

| Concentration difficulties | · Use organization techniques that help students manage time and stay on track.

· Ask students if using a highlighter to emphasize assignments that are priorities will help. · Step away from busy workplaces to provide directions in a quieter location. · Develop or have the student develop checklists for common tasks. |

| Distractibility | · Provide or allow students to use their own noise-canceling headphones or give them a private room to work.

· Provide a quiet space away from noise and busy office traffic and a “Do Not Disturb” sign so students can work without interruption. · Avoid allowing or encouraging multitasking. Have students complete one thing at a time. |

| Dyslexia | · Encourage use of appropriate read-aloud and voice-to-text software.

· Explain and provide a list of common or site-specific acronyms and other jargon. |

| Neurodiversity | · Sound sensitivity: offer a quiet break space, communicate expected loud noises (like fire drills), offer noise-canceling headphones.

· Tactile: allow modifications to the usual work uniform · Movement: allow the use of fidget toys, allow extra movement breaks, offer flexible seating · Use a clear communication style: o Avoid sarcasm, euphemisms, and implied messages. o Provide concise verbal and written instructions for tasks, and break tasks down into small steps. · Inform people about workplace etiquette, and don’t assume someone is deliberately breaking the rules or being rude. · Try to give advance notice if plans are changing and provide a reason for the change · Don’t make assumptions – ask a person’s individual preferences, needs, and goals. · Be kind, be patient |

| Poor organization | · Set aside 15 minutes at the end of the day to plan the next day’s work.

· Have students and all employees return important shared items to the same place each time they use them. · Consider a color-coding system for assignments or shelving. · Keep things visible on shelves, bulletin boards, or other places; avoid storage in drawers or closets. · Attach important objects physically to the place they belong. |

| Processing disorders | · Provide both written and oral instructions.

· Follow-up important conversations with a brief e-mail · Ask the student to make notes and provide them to you for review. · Use the teach-back method; ask the student to repeat the information back so you can be sure you covered everything (and they heard the key messages) |

Emphasis on Planning Ahead

Before rotations start, students with disabilities and preceptors should complete a practice walk-through at the rotation site to identify, modify, and make necessary adjustments.13 The experiential team must also understand the student’s career aspirations. Frank discussion will help all involved with rotation planning. The experiential team and the preceptor can address the students’ and preceptors’ concerns, needs, and goals in advance. Also, the person coordinating this process should identify and discuss costs and financial resources for the accommodation plan with all parties involved and determine who is responsible for the costs. This creates clear expectations. 13

If during the check-in or at any time a situation changes, the plan needs revision to find a more acceptable or effective reasonable accommodation or an urgent concern arises, the student or the preceptor should contact the school immediately.13

CONCLUSION

Preparing and executing accommodation can be challenging. Preceptors who develop skills in this area help student pharmacists develop communication, collaboration, and planning skills they will use and improve all during their careers. Preceptors also assess the actual barriers associated with the student’s disability in a controlled environment and help students learn how to mitigate the challenges associated with their disabilities in future employment. A PRO TIP is to keep in mind that many employees have disabilities or have slightly different learning styles. Learning how to accommodate them from students and schools of pharmacy will benefit your entire work force. It may even help you!

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

1. A student has been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a type of learning disorder. Which of the following BEST describes ADHD?

A. A disorder characterized by writing disabilities that appear as distorted or incorrect writing

B. A disorder that affects how people interact with others, communicate, learn, and behave

C. A disorder that causes ongoing patterns of inattention and/or hyperactivity that interferes with functioning and/or development

2. You observe that a student has difficulties counting, putting documents in numerical order, and calculating doses when the order specifies a mg/kg dosing. What type of disability is this MOST LIKELY to be?

A. Dyslexia

B. Dyscalculia

C. Dysgraphia

3. Once the school confirms a student’s site, what information can the school share with the preceptor?

A. The required accommodation

B. The student’s diagnosis

C. The student’s health information

4. How can the school of pharmacy help students with disabilities to be comfortable and meet their needs at various clinical sites?

A. Informing the site that the student will be doing all their clinical rotations at that site

B. Providing policies and student-specific accommodation plans that can be adjusted

C. Only using preceptors who have experience accommodating students with disabilities

5. Mary, a preceptor, is preparing for Elwin to start a rotation at her site. Elwin told the preceptor that he struggles with organization. They are identifying accommodation and exploring if they need to make any changes to the site. Which of the following is the most appropriate accommodation to keep the site organized for the student?

A. Color-code the shelving system in the pharmacy

B. Provide both written and oral instructions

C. Provide directions away from the workplace

6. A pharmacy student, Sarah, has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and will be going on her clinical rotation. She has been in communication with the school and the preceptor about accommodation, indicating her key limitation is distractibility. Which of the following is the is the BEST accommodation the preceptor can provide?

A. Encourage use of appropriate read aloud and voice to text software

B. Plan the days and weeks, setting achievable goals, and prioritizing tasks.

C. Provide a quiet space away and a “Do Not Disturb” sign

7. Which of the following factors would a preceptor consider when providing a reasonable accommodation?

A. The accommodation’s feasibility and financial cost

B. The student’s academic grade point average

C. The student’s specific diagnosis

8. Which answer correctly lists the steps when choosing an accommodation for a student?

A. Lower your expectations, assess whether the accommodation is meeting the student’s needs, analyze the required tasks

B. Maintain your expectations, analyze the required tasks, periodically assess whether the accommodation is meeting the student’s needs

C. Meet with the student, ask about the specific diagnosis of neurodiversity, develop a plan you think is suitable for the student

References

Full List of References

REFERENCES

1. Vos S, Kooyman C, Feudo D, et al. When Experiential Education Intersects with Learning Disabilities. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(8):7468.

2. Anxiety Disorders. National Institutes of Mental Health. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders

3. Autism Spectrum Disorder. National Institutes of Mental Health. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/autism-spectrum-disorders-asd

4. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. National Institute of Mental Health. Accessed August 5, 2023. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd

5. Dysgraphia. National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Accessed August 5, 2023. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/dysgraphia

6. Dyscalculia. Dycalculia.org. Accessed August 5, 2023. https://www.dyscalculia.org/

7. Dyslexia. National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Accessed August 5, 2023. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/dyslexia

8. Baumer N. What is Neurodiversity? Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-is-neurodiversity-202111232645

9. Neurodivergent. The Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/23154-neurodivergent

10. Austin RD, Pisano GP. Neurodiversity as a Competitive Advantage. Harvard Business Review. May-June 2017. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://hbr.org/2017/05/neurodiversity-as-a-competitive-advantage

11. Elliott HW, Arnold EM, Brenes GA, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder accommodations for psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2007;31(4):290-296.

12. Shrewsbury D. Dyslexia in general practice education considerations for recognition and support. Educ Prim Care. 2016;27(4):267-270.

13. Kieser M, Feudo D, Legg J, et al. Accommodating Pharmacy Students with Physical Disabilities During the Experiential Learning Curricula. Amer J Pharm Ed. Published online April 2, 2021:8426.

14. L’Ecuyer KM. Clinical education of nursing students with learning difficulties: An integrative review (part 1). Nurse Educ Pract. 2019;34:173-184.

15. Vos SS, Sandler LA, Chavez R. Help! Accommodating learners with disabilities during practice‐based activities. 2021;4(6):730-737.

16. Job Accommodation Ideas for People with Learning Disabilities. Learning Disabilities Association of American. Accessed August 5, 2023. https://ldaamerica.org/info/job-accommodation-ideas-for-people-with-learning-disabilities/

17. Horesh A. Conquer Anxiety in Clinical Rotations: A Guide for Medical Students. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://futuredoctor.ai/anxiety-in-clinical-rotations/