INTRODUCTION

Gallbladder disease (GBD; see Sidebar: Types of Gallbladder Disease) is the most common surgical emergency, responsible for 600,000 surgeries per year in the United States.1 Cholelithiasis, or gallstones, is one of the most common and costly gastrointestinal diseases, affecting more than 20 million Americans annually.2 An estimated 115 of every 100,000 of the world’s population will undergo gallbladder removal surgery every year.3

GBD is influenced by genetic and environmental factors, diet, physical activity, and nutrition. The healthcare team should encourage patients to incorporate healthy habits into their lifestyles to reduce the risk of GBD. This continuing education activity will discuss GBD pathology, risk factors, treatment, considerations post-cholecystectomy, and the pharmacy team’s role.

GALLBLADDER DISEASE

The Gallbladder

The gallbladder is the small pear-shaped organ located in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) of the abdomen beneath the liver. It is part of the biliary system, which is a series of ducts in the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas that drain into the small intestine.4 The gallbladder acts as a storage pouch for up to 50 mL of bile, also known as “gall.”5 Gall became a synonym for bile in the Middle Ages and also meant “embittered spirit.”5 In the late 19th century, gall was used to describe a person having boldness or insolence.4

Bile is a yellowish-brown alkaline surfactant (substance that decreases surface tension) continuously produced by the liver.1,2 It is composed of cholesterol, bilirubin, water, bile salts, phospholipids, and ions. The common bile duct carries bile from the liver to the gallbladder. Fatty foods and proteins released from the stomach into the small intestine stimulate the gallbladder to empty bile into the duodenum via the sphincter of Oddi, which facilitates digestion. Bile salts emulsify lipids in the intestines allowing absorption of dietary fats such as cholesterol and fat-soluble vitamins. Unused bile salts return to the gallbladder through the distal ileum and portal circulation.1,2

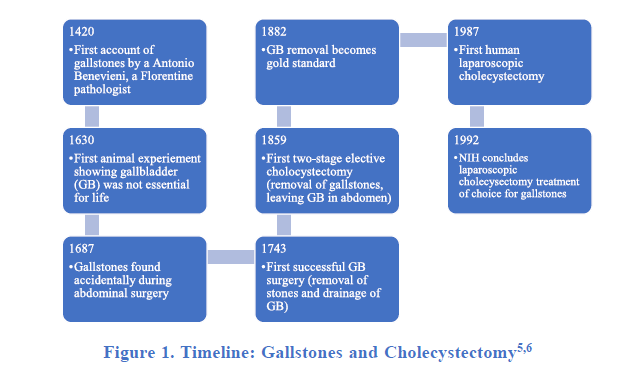

The gallbladder was probably more valuable centuries ago.5 Primitive humans were carnivorous hunters; meals were large, few, and far between.5 The gallbladder would have been crucial for digestion of large, high fat meals. The organ wasn’t considered nonessential until the late 1600s, after two Italian doctors discovered that animals could thrive without it.1 This discovery was forgotten until a German physician successfully performed the first cholecystectomy (surgical removal of the gallbladder) in a human in 1878.1,6 Figure 1 describes a brief history of the gallbladder, gallstones, and cholecystectomy beginning in the 15th century.

Today, the gallbladder assists in digestion of fat-soluble vitamins, proving important even for vegetarians.5 People can still live a healthy life after gallbladder removal; however, the risk of hepatic problems increases due to impaired fat digestion.5

Sidebar: Types of Gallbladder Disease2,8

- Biliary dyskinesia: gallbladder motility disorder caused by scarring or spasm of sphincter of Oddi, the valve that controls the flow of biliary and pancreatic secretions into the duodenum

- Cholangitis: inflammation of the biliary system

- Cholecystitis: inflammation of the gallbladder

- Choledocholithiasis: common bile duct stones

- Cholelithiasis: gallstones

- Gallbladder empyma: severe acute cholecystitis, a surgical emergency

- Gallbladder pancreatitis: inflammation of the pancreas caused by pancreatic duct obstruction by a gallstone

- Gallbladder perforation: a hole in the gallbladder wall

- Acute: generalized biliary peritonitis

- Subacute: acute plus pericholecystic abscess

- Chronic: cholecystoenteric fistula

- Gallbladder polyps: overgrowths or lesions in the gallbladder wall

This continuing education activity will focus on gallstones and their complications, which may include cholecystitis, choledocholithiasis, and cholangitis. Cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal) is the treatment mainstay for gallstones and pharmacist intervention is most valuable post-cholecystectomy.

Gallstones and Acute Cholecystitis

The most common gallbladder disease is gallstones.7 Gallstones commonly form from imbalances in bile constituents and biliary sludge (solids precipitated from bile) caused by slowed gallbladder motility or altered hepatic cholesterol metabolism. Hardened cholesterol or bilirubin become saturated in bile and crystalize, like rock candy, and can lodge in the common bile duct.7 Gallbladder hypomotility leads to delayed emptying, resulting in the formation of biliary sludge and consequently, gallstones.7

Bilirubin is a substance found in bile resulting from red blood cell breakdown in the liver. It is normally eliminated through the feces. Gallstones caused by bilirubin, or “pigment stones”, are rare and only account for approximately 10% of all gallstones.8 Pigment stones are commonly seen in individuals with blood disorders, such as sickle-cell anemia.8 Approximately 75% of gallstones in Western countries contain cholesterol as their major component.9

The presence of stones in the gallbladder is called cholelithiasis. Most patients with gallstones are asymptomatic and may not have any attributable symptoms during their lifetime.8 Asymptomatic cholelithiasis does not require treatment as the risk of symptom development is only about 10% at five years.8

Cholelithiasis becomes acute cholecystitis when gallstones block the cystic duct, causing the gallbladder to become inflamed and patients to become symptomatic. Biliary pain—also known as biliary colic—is the most common symptom of cholecystitis. Epigastric (upper-middle abdomen) pain lasting from 30 minutes to several hours radiates around or through the back and may be accompanied by heartburn, bloating, nausea, and/or vomiting. The sharp, stabbing pain generally follows food intake and peaks after the first hour. It is characteristically steady and is severe enough to interfere with activities of daily living. The pain is not relieved with a bowel movement. Women often describe biliary pain as being worse than childbirth.2,8

Cholecystitis pain from an acute episode usually subsides over one to five hours as the stone dislodges.3,10 The likelihood that patients experience repeated symptomatic episodes from their gallstones is approximately 38% to 50% annually.8 More than 90% of patients presenting with a single episode of biliary colic have recurrent pain within 10 years.13

Ultrasound is the best test for diagnosing gallstones and finds most patients with an average of two to 20 stones. The record-setting number of stones was found in England in 1987; a female patient had 23,530 stones removed.5 Computerized tomography (CT) can also be used for diagnosis, but it is less accurate than other imaging methods, detecting approximately 75% of gallstones.2 Providers can also diagnose by the presence of Murphy’s sign, or pain upon inhalation when the inflamed gallbladder meets the examiner’s hand.8 Other diagnostic markers include elevated liver function tests, white cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein.8 Patients presenting with acute cholecystitis may have experienced several bouts of biliary colic before diagnosis.

Acute cholecystitis diagnosis typically requires admission for pain management and intravenous (IV) fluid rehydration. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) like ketorolac, diclofenac or indomethacin combat inflammation and promote speedy recovery.8 NSAIDS are generally preferred to narcotic analgesics as they are equally effective with fewer adverse effects.2 A study of 324 patients given IV ketorolac or meperidine showed both drugs offered similar pain relief but patients in the NSAID group reported fewer adverse effects.2 Patients receive broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., ciprofloxacin, cefuroxime) to prevent or treat bacterial infection.8

Failure to properly treat cholecystitis can lead to severe inflammation, gangrene, sepsis, and life-threatening gallbladder perforation. Cholecystitis can also lead to gallstone pancreatitis if stones in the sphincter of Oddi are not cleared and block the pancreatic duct.2

Chronic Cholecystitis

Repeated episodes of cholecystitis or chronic irritation from gallstones can lead to chronic cholecystitis.11 Chronic cholecystitis more often presents with cholelithiasis (calculous) but can also exist without gallstones (acalculous). Symptomatic patients usually present with dull RUQ pain that radiates around the waist to the middle back. Most patients are afebrile.11

While acute cholecystitis symptoms are sharp and abrupt, chronic cholecystitis symptoms usually develop and worsen over weeks to months.11 Lab values normally elevated in acute disease may not be in chronic disease and therefore cannot be used in diagnosis. Ultrasound of the RUQ is the best diagnostic tool to evaluate the gallbladder for wall thickening and inflammation. Elective cholecystectomy is the preferred treatment for chronic cholecystitis. Patients who are not eligible for or who prefer not to undergo surgery should be closely monitored. A low-fat diet and other lifestyle modifications can help reduce symptom frequency.11

Pharmacists should recognize the differences between presentations of acute versus chronic cholecystitis and refer patients to the nearest emergency department if symptoms are severe.

Choledocholithiasis and Cholangitis

Choledocholithiasis, or common duct stones, are gallstones that have migrated from the gallbladder to the common bile duct via the cystic duct. Approximately 8% to 16% of patients with symptomatic gallstones will also have common bile duct stones.8 Common duct stones can be asymptomatic or may lead to complications such as gallstone pancreatitis or acute cholangitis. Cholangitis is inflammation of the biliary system that causes fever, jaundice, and abdominal pain (Charcot triad).8 Charcot triad becomes Reynolds pentad when hypotension and altered mental state are also present.8 These symptoms develop due to bile stasis and bacterial infection in the biliary tract.

Cholangitis is most commonly caused by gram-negative (Escherichia coli [25% to 50%], Klebsiella spp. [15% to 20%], Enterobacter spp. [5% to 10%]) intestinal bacteria, and less often by gram-positive bacteria (Enterococcus spp. [10% to 20%]).8 Patients require prompt treatment with IV antibiotics such as a broad-spectrum cephalosporin or ciprofloxacin.8 Pharmaceutical intervention should be followed by stone removal to prevent septicemia (systemic blood infection), which can be fatal. Most clinicians recommend that common bile duct stones be removed once discovered, even when asymptomatic.8

Risk Factors

Several genetic and environmental factors contribute to gallstone development. Patients with first-degree relatives with history of cholelithiasis are at a three times higher risk of gallstones.8 Approximately 60% of patients with acute cholecystitis are female, but the illness is generally more severe in males.2 Women experience a higher prevalence because of estrogen’s effects on cholesterol metabolism.12 Estrogen increases cholesterol synthesis and decreases bile acid production.12 Progesterone in pregnancy decreases gallbladder contractility leading to stasis, making gallstones 10 to 15 times more common in women who have been pregnant.8,12 Women with history of biliary colic, gallstones, and the like should be aware of how hormones may affect their risk for recurrence. This is valuable information for pharmacists to consider and an appropriate place to intervene and educate.

European and American populations are more likely to develop gallstones, and Black people of African descent are least likely. Prevalence is highest in Native American populations, with 60% incidence in the Pima Indian populace of southern Arizona.8 Table 1 summarizes risk factors for GBD.2,8,13

| Table 1. Risk Factors for Developing Gallbladder Disease2,8,14-16 |

| Demographics

· Ethnicity (American Indians, Chilean and Mexican Hispanics)

· Family history

· Female gender (10:1 female:male)

· Older age

Diet

· High fat, calorie, and refined carbohydrate intake

· Low fiber and unsaturated fat intake

· Total parenteral nutrition

Lifestyle

· Pregnancy and multiple pregnancies

· Persistent fasting or very low-calorie diet

· Rapid weight loss (i.e., bariatric surgery)

· Sedentary

Medications

· Estrogen therapy or oral contraceptives

· Some hypoglycemic medications (GLP-1RAs)

· Chronic use of gastric acid suppressants (H2RAs, PPIs)

· Ketamine abuse

Heath Conditions & Other Factors

· Alcoholic liver cirrhosis

· Dyslipidemia (elevated triglycerides and low HDL)

· Gallbladder motor dysfunction

· Gastrointestinal surgery

· Metabolic syndrome, gallbladder, or intestinal stasis

· Short bowel syndrome

· Type 2 diabetes mellitus

|

GLP-1RAs, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists; H2RAs, histamine-2-receptor antagonists; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; PPIs, proton-pump inhibitors.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1) receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are notable for their glucose control and cardiovascular risk reduction for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and more recently, for weight loss. Their link to GBD is controversial as GLP1 inhibits gallbladder motility and delays gallbladder emptying.14 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 76 randomized clinical trials shows an association between GLP-1RA use and elevated GBD risk. The risk for gallbladder or biliary diseases were more prominent with higher doses, longer duration, and when used for weight loss.14 Clinicians should discuss the benefits of using these hypoglycemics for type 2 diabetes or weight loss and whether they outweigh the risk for GBD. Pharmacists can educate patients initiating GLP-1RAs about their benefits, risks, and implications with past medical history of or additional risk factors for GBD. Multiple GLP-1RAs are available in varying doses and pharmacists should continue to counsel patients as doses are increased over time.

Chronic use of gastric acid suppressants may cause cholelithiasis.15 These drugs impact gut microbiome and may slow gallbladder motility leading to delayed gallbladder emptying. A recent prospective cohort of 0.47 million participants found that regular use of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) resulted in increased cholelithiasis risk.15 Physicians should be aware of this association when prescribing these medications, especially for patients requiring long-term use or those already at high risk for gallstones. Pharmacists should keep these risks in mind when filling prescriptions for their patients on long-term or high-dose H2RAs and PPIs.

Ketamine abuse has been associated with chronic biliary colic. Ketamine was developed in 1962 as an anesthetic.16 “Street ketamine”, a close analogue of ketamine, is commonly used for its euphoric effects. Ketamine’s onset of action after oral ingestion is about ten minutes and its hallucinogenic effects are short acting, lasting up to two hours. The most common signs of ketamine abuse are hypertension, tachycardia, and abdominal tenderness. Ketamine abuse is also associated with impaired consciousness, dizziness, abdominal pain, and lower urinary tract symptoms.16 Case reports have shown ketamine abusers presenting with severe bladder dysfunction and recurrent episodes of epigastric pain due to a dilated common bile duct not associated with gallstones.16 Clinicians should collect detailed drug histories for patients presenting with recurrent abdominal pain, namely biliary colic.

Diets characterized by increased caloric intake with highly refined sugars, high fructose, low fiber, high fat, and consumption of fast food increase the risk of gallstone formation.9 Nutrition and lifestyle changes may be beneficial in the prevention of gallstones. Increased physical activity, consuming smaller more frequent meals, and “heart healthy” diets low in cholesterol and fat and high in fiber can reduce risk of cholelithiasis.7 Fat should not be completely cut out of the diet as too little fat can also precipitate gallstone formation.

Weight loss can reduce gallstone risk, but rapid weight loss achieved by low-calorie diets (less than 800 kcal/day) or bariatric surgery can cause gallstones.2,9 Patients should seek professional advice before starting diets promoting very low caloric or high fat intake to achieve rapid weight loss (i.e., Atkins, ketogenic). Pharmacists should be aware of patients who have recently undergone bariatric surgery or are taking drugs or supplements for weight loss. These patients may be at a higher risk for gallstones, especially those with past medical histories of GBD or abdominal colic symptoms.

Some foods and medications seem to be associated with a reduced risk of gallstones:

- Statins alter bile cholesterol and thus affect gallstone formation, suggesting a role in prevention. While the relationship between statins and gallstone formation is conflicting, studies report reduction in symptomatic gallstone disease with statin use.17

- Ezetimibe, a selective NPC1L1 inhibitor, has been associated with a reduced incidence of cholesterol gallstones in animal studies. The mechanism involves reduced amounts of absorbed cholesterol, decreasing biliary cholesterol saturation, and in turn, reduced rate of cholesterol gallstone formation.12

- Vitamin C supplementation has been shown to reduce gallstone prevalence. Researchers have studied vitamin C supplementation’s effects in gallstone formation in guinea pigs; those deficient in vitamin C more often develop gallstones. An observational study of a randomly selected population in Germany (n = 2129) showed a positive correlation between regular vitamin C intake and a reduced gallstone incidence.18

- Coffee consumption may also offer a protective effect against gallstone formation. Studies suggest coffee stimulates cholecystokinin release, enhancing gallbladder contractility, thereby reducing bile cholesterol crystallization. A 2019 observational analysis published in the Journal of Internal Medicine found a 23% decrease in gallstone formation in subjects consuming six or more cups of coffee daily.19

- A small study conducted in Spain shows that regular consumption of olive oil containing monounsaturated and polyunsaturated omega-6 fatty acids may prevent gallstones. Similarly, fish (omega-3 fatty acids) and fish oil may reduce triglycerides and prevent gallstones. A group of participants with hypertriglyceridemia taking fish oil supplements for a seven-week study in the Netherlands experienced improved gallbladder motility and a decrease in triglycerides.10

TREATING GALLBLADDER DISEASE

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the most common way to identify and remove common duct stones. ERCP is minimally invasive and carries the risk of acute pancreatitis.8 This diagnostic tool may also identify duct strictures at which time stents are placed to reduce obstruction and improve biliary flow.8,10 Timely stent removal (within three to six months) is crucial to prevent occlusion, stent migration, or cholangitis.22 Cholecystectomy is the definitive treatment for symptomatic gallstones and should commence within 48 hours of symptom onset during the acute inflammatory process, before tissue thickening or scarring develops.8,10

Surgical Intervention: Cholecystectomy

The first gallstone removal surgery was a coincidence. In the mid-19th century, a physician was performing investigative surgery on a female patient, and when he cut into her gallbladder, several bullet-like objects spilled out.5 The first planned gallbladder removal was performed 15 years later.5 Before the early 1900s, the surgery was performed through an incision in the RUQ (Kocher’s incision, named after Emil Theodor Kocher, a Swiss physician and medical researcher who performed the first successful cholecystectomy in 1878).6,8 This invasive procedure was outmoded a few years after Erich Muhe, a German surgeon, performed the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 1985.8 Today, surgeons perform more than 98% of cholecystectomies laparoscopically, over 70% of which are outpatient day surgeries.8

Cholecystectomy is associated with fewer gallbladder-specific complications and shorter length of hospital stay when surgery is elective or performed as a single emergency visit without previous surgical admissions.3 A population-based cohort study of outcomes following surgery for benign GBD showed poorer outcomes and risk of readmissions with delayed cholecystectomy. Many studies define emergency or early surgical intervention as operations performed within 48 to 72 hours of symptom onset. A study of 14,200 patients in Canada discovered patients experienced fewer complications when surgery was performed within seven days of hospital admission.3 These studies show value in offering emergency surgery over delaying cholecystectomy for patients presenting with benign GBD.3

Antibiotic prophylaxis is not routinely recommended for low-risk patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.13 High-risk patients (age older than 60, type 2 diabetes, acute colic within 30 days of surgery, jaundice, acute cholecystitis, or cholangitis) may benefit. Providers should limit prophylaxis to IV cefazolin 1 g as a single dose one hour prior to surgery.13

Several studies suggest that pain management before or during, and after laparoscopic cholecystectomy can reduce post-operative pain. A 2018 review of 258 randomized control trials recommended a basic analgesia technique: acetaminophen plus an NSAID or cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor with local anesthetic infiltration.21 Opioids are reserved for breakthrough pain.21

Patients are generally discharged a few hours after surgery. Surgeons should be on alert for early signs of complications if there is divergence from the usual course of rapid recovery post-op. Extreme pain shortly after surgery may indicate intra-peritoneal leakage of bile or bowel contents.8 Persistent hypotension (low blood pressure) and pain can suggest bleeding. Re-laparoscopy may be necessary to identify and repair these problems and is preferred to diagnostic imaging.8

Removal of the gallbladder will not cause weight loss/gain or vitamin deficiencies. Patients should be able to tolerate foods they couldn’t before surgery, but providers should advise them to add those foods back into their diet very slowly. Following gallbladder removal, the liver will continue to make bile, but instead of storing it in the gallbladder, it will drain into the stomach and small intestines. Patients might experience three to five days of soreness post-op and are expected to fully heal within four to six weeks.7

Diarrhea and bloating due to alternation of biliary flow are common short-term occurrences after surgery.22 A small percentage (1% to 2%) of patients will have loose stools each time they eat greasy or high-fat meals.7 A cystic duct remnant is also possible, potentially leading to stone formation, causing Mirizzi syndrome. Mirizzi syndrome is characterized by fever, jaundice, and RUQ pain due to common hepatic duct obstruction caused by compression from the impacted stone in the remnant cystic duct.22 Endoscopic removal of the stone may be adequate. In rarer cases, surgical excision of the remnant duct may be necessary to prevent further complications.22

Pharmacologic and Other Non-Surgical Interventions

Nonoperative methods exist for patients unwilling or unable to undergo surgical intervention. Contraindications for laparoscopic cholecystectomy include10,13

- Absolute: gallbladder cancer (see Sidebar: Gallbladder Cancer), general anesthesia intolerance, giant gallstones, morbid obesity, uncontrolled bleeding disorder

- Relative: advanced cirrhosis/liver failure, bleeding disorder, peritonitis, previous upper abdominal surgeries, septic shock

Gallbladder Cancer20

Gallbladder cancer is a rare malignancy but accounts for almost 50% of biliary cancers. Biliary cancers have a poor five-year survival rate and a high recurrence rate. Factors affecting prognosis are stage at discovery, tumor location, operability, response to chemotherapy, and presence and location of metastases. Early-stage gallbladder cancer may be curable with surgical resection.

Oral bile acid dissolution drugs include ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol) and chenodeoxycholic acid (chenodiol).23 Table 2 lists dosing and adverse effects of these medications. Smaller gallstones (0.5 to 1 cm) may be better suited for pharmaceutical intervention but may take up to 24 months to dissolve.2 Ursodiol is preferred over chenodiol due to its safer adverse effect profile. Use-limiting adverse effects of chenodiol include dose-dependent diarrhea, hypercholesterolemia, hepatotoxicity, and leukopenia.2 Recurrence rate is more than 50% and fewer than 10% of patients with symptomatic gallstones are candidates for this treatment.13

Table 2. Oral Bile Acids2,23,24

| Drug |

Dosage |

Duration |

Adverse Effects |

| Ursodiol

(Actigall) |

8-10 mg/kg/day given in 2-3 divided doses |

Symptom relief after 3-6 weeks, results may take 6-24 months, continue for 3 months after documented dissolution |

Dyspepsia (>10%), nausea, vomiting, pruritis, headache, diarrhea, dizziness, constipation |

| Chenodiol (Chenodal) |

250 mg twice daily for 2 weeks, increase dose by 250 mg/day weekly until maximum tolerable dose reached (13-16 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses) |

Discontinue if no response by 18 months, safety not established beyond 24 months |

Dose-dependent diarrhea* (>10%), hypercholesterolemia, leukopenia, increased serum aminotransferase |

* If diarrhea occurs, reduce dose and restart at previous dose when symptoms resolve.

Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is a noninvasive option for symptomatic patients.13 Complications such as biliary pancreatitis and liver hematoma are rare, however stone recurrence is common. Recent studies show this procedure is beneficial for large pancreatic and common bile duct stones with similar pain relief and duct clearance outcomes compared to surgery.13

The initial approach for pregnant women with symptomatic gallstones is supportive care.13 Meperidine is the choice agent for pain control as NSAIDs are not recommended in pregnancy.13 Chenodiol is contraindicated in pregnancy.24 Ursodiol has been used in pregnant patients for intrahepatic cholestasis; safety and efficacy of use for gallstones has not been studied.13,23 Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, when indicated, is safe in all trimesters.13

POST-OPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS AND THE PHARMACY TEAM

Post-Cholecystectomy Syndrome

Persistent or delayed onset abdominal pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy may indicate post-cholecystectomy syndrome (PCS).22 Additional PCS symptoms include fatty food intolerance, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, heartburn, indigestion, flatulence, and jaundice. PCS often occurs in the post-operative period but can present months or years after surgery.22 Cholecystectomy carries a low mortality risk, but approximately 10% of patients undergoing cholecystectomy each year develop PCS.22 The risk increases with urgent surgeries and 20% of patients will develop PCS regardless of choledochotomy (surgical incision of common bile duct).22

PCS etiologies can be extra-biliary (pancreatitis, pancreatic tumors, hepatitis, esophageal diseases, mesenteric ischemia, diverticulitis, peptic ulcer disease) or biliary (bile salt induced diarrhea, retained calculi, bile leak, biliary strictures, stenosis, sphincter dyskinesia) in nature.22 Pathophysiology is related to alterations in bile flow and bile is the main trigger for patients with gastroduodenal symptoms or diarrhea.

The likelihood of diarrhea post-cholecystectomy ranges from 2% to 50% according to various studies.25 Diarrhea usually improves or resolves over the course of weeks to months. As discussed, in the gallbladder’s absence, bile flows straight from the liver into the small intestine continuously. This redirection of bile flow can overwhelm the ileum’s capacity for reabsorption, leading to increased bile acids in the colon and subsequently cholerheic diarrhea (also known as bile acid diarrhea).25 Patients may respond to treatment with bile acid sequestrants, including cholestyramine and colestipol.25

Bile acid sequestrants release chloride and bind bile acid in the intestines, preventing bile acid reabsorption. The drugs do not leave the gastrointestinal tract and are eliminated in the feces. They are indicated for hypercholesterolemia but patients use them off-label for chronic diarrhea due to malabsorption (Table 3). The most common adverse effect of bile acid sequestrants is constipation, which occurs in more than 10% of patients.26,27 Clinicians should instruct patients to drink plenty of fluid and increase dietary fiber. Most adverse effects are gastrointestinal-related (e.g., abdominal pain, flatulence, bloating, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, dysphagia), and others include26,27

- Cholestasis and cholecystitis (with colestipol only)

- Dental bleeding and caries

- Diuresis, dysuria, and burnt odor to urine

- Edema

- Worsened hemorrhoids

Bile acid sequestrants bind vitamin K and folate so prescribers should monitor for deficiencies of both. Patients should supplement with folate. Patients may supplement with vitamin K; however preexisting coagulopathy is a contraindication. These drugs should be used with caution in patients with renal insufficiency.26,27

Table 3. Bile Acid Sequestrants26,27

| Drug |

Dosage |

Administration |

| Cholestyramine

(Prevalite, Questran) |

2-4 g daily as a single dose or divided, increase by 4 g weekly based on response and tolerability, maximum 24 g/day |

Mix dose in 60-180 mL of any beverage, soup, or pulpy fruit, should not be sipped or held in mouth for long periods*

Take with meals, administer oral medications ≥1 hour before or 4-6 hours after dose |

| Colestipol (Colestid) |

Granules: 5 g once or twice daily, increase by 5 g in 1-2 month intervals, maintenance dose 5-30 g once daily or in divided doses

Tablets: 2 g once or twice daily, increase by 2 g in 1-2 month intervals, maintenance dose 2-16 g once daily or in divided doses |

Administer other medications ≥1 hour before or 4 hours after dose

Granules: do not administer in dry form to avoid GI distress or accidental inhalation, should be added to at least 90 mL of any beverage, soup, or pulpy fruit

Tablets: administer one at a time; swallow whole; do not cut, crush, or chew |

*May cause tooth discoloration or enamel decay. GI, gastrointestinal.

PCS is a temporary diagnosis until further investigation establishes organic or functional diagnosis.22 Misdiagnosis of preexisting conditions is possible. The healthcare team should order a complete blood count and consider patients re-presenting with ongoing or new-onset abdominal pain post-cholecystectomy for CT scan.8 Presence of gas and fluid in the gallbladder bed may be normal but fluid or gas build-up elsewhere may indicate a bile leak. Elevated liver function tests may also suggest a bile leak or retained common bile duct stone. The most common cause of PCS is the presence of stones in the biliary tree.10 ERCP, both diagnostic and therapeutic, is the most common procedural approach to PCS.22

Medication: Treatment Goals

Pharmacologic treatment goals in GBD are to prevent complications and reduce morbidity.22 Administration of bulking agents like psyllium fiber can help patients with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and/or diarrhea. Psyllium husk (Metamucil, Benefiber) is an over-the-counter (OTC) option for patients looking to increase fiber intake. It is usually used to treat constipation and works by stimulating intestinal contractility, speeding up the movement of stool through the colon.28 Psyllium can also treat diarrhea by soaking up excess water from the intestines, bulking stool, and promoting regularity.28 Psyllium may reduce absorption and effectiveness of many medications; it is important that patients seek pharmacist counseling before initiating a psyllium fiber regimen.

Antispasmodics (e.g., loperamide) may help patients with IBS symptoms like cramping. Cholestyramine may help symptoms of diarrhea alone. Antacids (Maalox, Mylanta, Tums), H2RAs (e.g., famotidine), and PPIs (e.g., esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole) can improve gastritis or gastric reflux symptoms by reducing acid production.22 One study showed a correlation between dyspeptic symptoms and gastric bile salt; these patients may benefit from bile acid sequestrants.22 Patients should consult their gastroenterologist for recommended dosing of these drugs, as they may vary depending on clinical presentation and severity of symptoms.

The Pharmacy Team’s Role

Pharmacists and pharmacy technicians are integral members of the healthcare team. Pharmacists can educate patients about GBDs, the risk factors for their development, and how to mitigate them with a proper diet and exercise.

Pharmacy technicians can help by directing patients in the right direction when looking for OTC antacids, fiber supplements, or anti-diarrheal agents. Many patients may not ask questions about OTC products before purchase. Pharmacy technicians are often the patients’ first point of contact in the pharmacy and should ask open-ended questions at the register before or during the transaction.

Patients should use the products as directed by their gastroenterologists. Pharmacy technicians should refer patient questions relating to administration, dosing, adverse effects, and drug interactions to the pharmacist on duty. Consider possible scenarios that may arise in the pharmacy and how pharmacy technicians and pharmacists should approach them:

- Mark is a pharmacy technician at XYZ Pharmacy. Jaclyn enters the pharmacy, approaches the pick-up window, and places several OTC items on the counter. She states she would like to pick up a prescription her doctor called in today. Mark retrieves Jaclyn’s prescription and notices it is for omeprazole 40mg. The items on the counter include Tums, famotidine 20mg, docusate sodium 100mg, and lansoprazole 30mg. Mark knows that omeprazole and lansoprazole are in the same drug class. What questions can Mark ask Jaclyn? Should Mark involve the pharmacist?

- Jaclyn comes back to the pharmacy a week later to pick up a prescription for cholestyramine. She wants to know if she can take this with omeprazole and famotidine. Mark refers Jaclyn’s question to the pharmacist. How should the pharmacist respond to Jaclyn’s question and what counseling points are important to include?

CONCLUSION

Gallbladder diseases typically occur secondary to cholelithiasis. Most gallstone cases are asymptomatic, but some develop into symptomatic disease. Factors that may increase GBD risk include gender, age, family history, ethnicity, diet, and medical conditions. Surgical gallbladder removal is the most common treatment, but many nonsurgical alternatives exist when surgery is nonpreferred or contraindicated. Additionally, PCS can occur months to years after surgery and treatment should be directed based on specific diagnosis post-examination. Healthcare providers should collaborate to develop the best procedural and/or pharmaceutical treatment plan as each patient’s clinical presentation and symptoms will vary.

The pharmacy team should take an active role in GBD management, especially following cholecystectomy. Pharmacy technicians should be weary when patients complain of abdominal pain or attempt to purchase multiple OTC products to treat their symptoms; they should relay specific disease- and drug-related questions to the pharmacist on duty. GBD is a common and highly manageable condition, and patients can live normal and healthy lives once symptoms are properly controlled and treated.