Learning Objectives

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to

| · Discuss the importance of knowing about a patient’s dietary supplement usage |

| · Identify commonly used dietary supplements, their regulation, and the value of certification |

| · Recognize potential medication-dietary supplement interactions |

| · Demonstrate the ability to locate different sources of information about dietary supplements |

After completing this application-based continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to

| · Discuss the importance of knowing about a patient’s dietary supplement usage |

| · Identify commonly used dietary supplements, their regulation, and the value of certification |

| · Recognize potential medication-dietary supplement interactions |

| · Recognize the need for pharmacist counseling when a patient is taking a dietary supplement |

Release Date: January 16, 2026

Expiration Date: January 16, 2029

Course Fee

Pharmacists: $7

Pharmacy Technicians: $4

There is no grant funding for this CE activity

ACPE UANs

Pharmacist: 0009-0000-26-002-H05-P

Pharmacy Technician: 0009-0000-26-002-H05-T

Session Codes

Pharmacist: 23YC01-FKE24

Pharmacy Technician: 23YC01-EFK68

Accreditation Hours

2.0 hours of CE

Accreditation Statements

| The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider of continuing pharmacy education. Statements of credit for the online activity ACPE UAN 0009-0000-26-002-H05-P/T will be awarded when the post test and evaluation have been completed and passed with a 70% or better. Your CE credits will be uploaded to your CPE monitor profile within 2 weeks of completion of the program. |  |

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-label and Investigational Drug Use

The material presented here does not necessarily reflect the views of The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy or its co-sponsor affiliates. These materials may discuss uses and dosages for therapeutic products, processes, procedures and inferred diagnoses that have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. A qualified health care professional should be consulted before using any therapeutic product discussed. All readers and continuing education participants should verify all information and data before treating patients or employing any therapies described in this continuing education activity.

Faculty

Jennifer Salvon, RPh

Clinical Pharmacist

Mercy Medical Center

Springfield, MA

Adjunct Faculty Member

University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy

Storrs, CT

Faculty Disclosure

In accordance with the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Criteria for Quality and Interpretive Guidelines, The University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy requires that faculty disclose any relationship that the faculty may have with commercial entities whose products or services may be mentioned in the activity.

Jennifer Salvon does not have any relationships with ineligible companies and therefore has nothing to disclose.

ABSTRACT

Consumer consumption of dietary supplements is at an all-time high. Available products number in the tens of thousands, generating millions in annual spending. Increasing interest in overall health and wellness, preventive medicine, and immune function contribute to the rise in usage. It is a common misconception that dietary supplements are safe because they are “natural.”

Ingestion of dietary supplements poses serious health risks including adverse reactions, drug interactions, and toxicity. Adulterated, mislabeled, and contaminated products exist in the marketplace, further increasing consumer risk. Existing federal regulation and oversight for supplements differs from prescription and over-the-counter medications, occurring primarily on a post-marketing basis. Self-reporting by consumers, healthcare professionals, and industry personnel identifies these issues. Patients often omit dietary supplements from medication histories, leaving healthcare professionals unaware that patients are using them. While misinformation abounds on the Internet, many online clinically-backed sources exist.

CONTENT

Content

Introduction

Consuming natural substances to produce a desired effect on the body dates back thousands of years to ancient Egypt, Rome, China, and many other cultures. Records from early Mesopotamia include written formulas using many oils still in use today, including cedar, cypress, and licorice. Around 300 B.C., the Greek philosopher Theophrastus described the medicinal benefits of natural substances in his History of Plants. Throughout the centuries, many philosophers, scientists, and physicians continued collecting, combining, and documenting the use of natural products to treat different illnesses.1

As the science of medicine developed, so did the science of pharmacology. Isolation of the active ingredients found in herbal substances lead to the development of synthetic compounds with similar properties. The first synthetic medication, chloral hydrate, derived from chloroform and discovered in the 1800s by German chemist Justus von Lieberg, is still in use today.2

Fast forward to modern day, and the interest and use of prescription medications, over-the-counter (OTC) products, and dietary supplements are at an all-time high. In 2020, consumers filled 6.3 billion prescriptions in the United States3 (U.S.) and purchased more than 6 billion OTC products.4 The dietary supplement market reached an unprecedented level in 2020 with a global spend of $61.2 billion. Experts predict it will reach $128.64 billion by 2028.5

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 acute respiratory coronavirus, significantly impacted our perception and approach to healthcare.6 More and more people use complementary and alternative approaches to healthcare than ever before.7 For example, sales of elderberry supplements more than doubled and zinc products quadrupled shortly after the pandemic's start.8

Pharmacists, widely recognized as drug information experts, and pharmacy technicians routinely field consumers' questions about dietary supplements. Many pharmacists lack the necessary knowledge or don't know where to look to answer these questions. Pharmacy schools educate future pharmacists on prescription and OTC medications with courses about nutrition and dietary supplementation, if offered, available as electives. This continuing education activity presents information about dietary supplements through a series of seven common pharmacy situations and lets learners in on seven secrets they can apply to their practices.

Situation: Continuing education is a professional requirement many pharmacists find tedious. Looking through the UCONN online CE library and seeing a new continuing education activity entitled ‘Seven Secrets of Patient Safety with Dietary Supplements,’ a pharmacist remarks to the pharmacy team, "What a waste, no one even takes dietary supplements."

Secret #1: Almost 60% of people in the United States used a dietary supplement in the last 30 days.11,12

Dietary supplements crowd the aisles in drug stores, supermarkets, warehouse clubs, and even corner convenience stores. The sheer number of products is staggering. The Dietary Supplement Database (DSLD) is an online, searchable database developed by the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The database contains product labeling information on dietary supplements sold in the United States, including both on and off-market products. DSLD currently lists more than 140,000 labels.9

In the early 1960s, the National Center for Health Statistics began a program named the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). NHANES is a continuous program focusing on various health and nutritional measurements and assesses adults' and children's health and nutritional status in the U.S.10 Scientific and technical journals publish the study results.

One section of the program assesses dietary supplement use among adults. Results from the 2017-2018 NHANES show that11,12

- 57.6% of adults 20 years or older used a dietary supplement in the past 30 days

- Women (63.8%) had a higher utilization than men (50.8%)

- Use of dietary supplements increased with age, with women 60 years or older reporting the highest usage at 80.2%

- Use of multiple dietary supplements increased with age

- Most common dietary supplements used by all age groups include multivitamin-mineral supplements, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids

The Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN) is a trade association for the dietary supplement and functional food industry. Annually, the CRN performs a survey gathering data on consumer use of dietary supplements. The 2019 survey conducted by the CRN underscored dietary supplement usage with the following results13:

- 77% of US adults take dietary supplements, including 79% of American women and 74% of males

- Top reasons for taking supplements included:

- Energy

- Immune health

- Filling nutrient gaps

- Healthy aging

- Heart health

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted our perception and approach to healthcare.6 As of August 5, 2022, SARS-CoV-2 has infected more than 580 million people worldwide.14 Interest in boosting our overall immunity and protecting ourselves from viral infections has dramatically increased as a result.7 Many vitamins and minerals play essential roles in proper immune function.7,15 Sales of supplements associated with boosting immunity increased over the last two years, including vitamins C and D, zinc, omega-3, garlic, ginger, and turmeric.16

Table 1. Common Dietary Supplements and Potential Uses7,17,18

| Dietary Supplement | Potential Use |

| Black Cohosh | Menopausal symptoms |

| Calcium | Dyspepsia

Osteoporosis Premenstrual syndrome |

| Echinacea | Prevention and treatment of the common cold

Promotion of wound healing |

| Elderberry | Prevention of upper respiratory tract infections

Reduction in duration and severity of symptoms of the common cold |

| Folic acid | Folate deficiency

Kidney failure Neural tube defects |

| Ginkgo | Anxiety

Dementia Memory improvement Premenstrual syndrome |

| Ginger | Dysmenorrhea

Nausea and vomiting Osteoarthritis |

| Ginseng | Cognitive function

Erectile dysfunction |

| Iron | Anemia

Restless leg syndrome |

| Magnesium | Constipation

Dyspepsia |

| Melatonin | Sleep disorders |

| Multivitamin with minerals | General supplementation |

| Omega-3 fatty acids

|

Alzheimer’s disease

Cardiovascular disease Dementia Depression Reduction of triglycerides |

| Potassium | Hypokalemia

Hypertension Kidney stones |

| Probiotics

|

Atopic dermatitis

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea Irritable bowel syndrome |

| St. John’s Wort | Anti-depressant

Menopausal symptoms |

| Turmeric | Allergic rhinitis

Osteoarthritis Pruritis |

| Valerian | Insomnia |

| Vitamin A | Aging skin

Healthy vision |

| Vitamin B-12 | Vitamin B-12 deficiency |

| Vitamin C | Anemia

Antioxidant effects Prevention of the common cold Vitamin C deficiency |

| Vitamin D | Osteomalacia

Osteoporosis Vitamin D deficiency |

| Vitamin E | Alzheimer's disease

Dysmenorrhea Premenstrual syndrome |

| Zinc | Acne

Depression Diabetes Diarrhea Treatment of common cold |

Eating a healthy diet is essential for good health and nutrition. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans advise professionals, including policymakers, health care providers, and nutrition educators, about what to eat to meet the body’s nutritional needs. It emphasizes eating a diet rich in nutrient-dense foods, such as fruits and vegetables, as the best way to meet the body’s nutritional needs. The guideline identifies specific populations in which dietary supplementation may be necessary, such as women who are pregnant or lactating and adults older than 50.19

In addition to these defined special populations, many pharmacy patients may find it necessary to take specific vitamins or minerals due to medication-induced nutrient deficiencies.

Table 2. Examples of Nutrient Depletion Induced by Medications7,17

| Nutrient | Medication(s) | Mechanism |

| Vitamin D | Anticonvulsants

|

Increase hepatic metabolism |

| Bile acid sequestrants

|

Decrease absorption | |

| Orlistat

|

Decrease absorption | |

| Magnesium

|

Estrogens

|

Decrease serum levels by increasing uptake into tissues |

| Loop diuretics

|

Increase excretion | |

| Proton pump inhibitors

|

Decrease absorption | |

| Vitamin B12

|

Biguanides

|

Decrease absorption |

| Proton pump inhibitors

|

Decrease absorption | |

| H-2 blockers

|

Decrease absorption | |

| Potassium | Loop diuretics

|

Increase excretion |

| Thiazide diuretics

|

Increase excretion | |

| Corticosteroids

|

Increase excretion |

The pharmacist's dismissal of dietary supplement education is understandable. No one wants to waste precious time on irrelevant continuing education. However, the facts presented here illustrate the need for pharmacist education on dietary supplements.

Pause and ponder: A patient presents information about taking lemon and baking soda tea to prevent COVID-19 infection and asks you if it really works. How would you approach this conversation?

Situation: Sunday afternoons sometimes (but not often!) present the opportunity to catch up on administrative activities. While completing an inventory reconciliation of the vitamin section, a technician inquires, "Why does the FDA approve so many different products?" Looking up distractedly from the CII safe count, the pharmacist pauses, then replies in a weary voice, "You know, I’m not sure, probably just to make it more confusing for us."

Secret #2: Regulatory oversight of dietary supplements differs from prescription and OTC medications.

What is a Dietary Supplement?

On the most basic level, a dietary supplement is a substance consumed to add nutrients to a diet or to lower the risk of certain health problems. The use of natural substances has been around for millennia, but it is only within the last five decades that countries worldwide have formalized language and regulations around dietary supplements. Terminology, quality control, and safety assessment differ depending on the country and governing legislative body.20

In 1994, the United States Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), an amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. DSHEA defines the term dietary supplement as a product intended for ingestion and containing an ingredient that supplements the diet. Dietary supplement labeling must include the term ‘dietary supplement’ or an equivalent term such as ‘herbal supplement’ or ‘magnesium supplement.’ DSHEA also stipulates that a dietary supplement must be free of contamination, adulteration, and properly labeled.21 We will discuss dietary supplement product integrity and labeling later in this activity.

According to DSHEA, dietary supplements include vitamins, minerals, herbs, other botanicals, amino acids, and live microbials (probiotics). Dietary supplements are available in many different formulations including tablets, capsules, soft gels, gel caps, powders, and liquids.21

DSHEA defined the term ‘new dietary ingredient’ as an ingredient that meets the above criteria and was unavailable in the U.S. before October 15, 1994. If manufacturers want to market a product containing a new dietary ingredient, they must notify the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before marketing. The FDA then reviews the product for safety but not effectiveness.21

Regulation of Dietary Supplements

The FDA and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) share regulation and oversight of dietary supplements. The FDA is responsible for the information provided on dietary supplement product labeling, including the package labeling, product inserts, and information available at the point of sale. The FTC monitors dietary supplement advertising, ensuring advertisements are truthful, substantiated, and not misleading. Both agencies have the authority to address violations and work together to ensure their efforts are consistent with one another.22

The FDA does not have the authority to approve dietary supplement products before manufacturers market, distribute, and sell them to consumers. Manufacturers are responsible for ensuring the products they produce and distribute meet all quality standards defined by federal law. Quality standards include22

- Ensuring the safety of the dietary ingredients used in the product

- Following current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP)

- Meeting all product labeling requirements

- Ensuring substantiation of all claims made about the product

- Ensuring products are free of adulteration or misbranding

cGMP, defined and regularly updated by the FDA, establish the minimum requirements for manufacturing, packaging, and labeling products to ensure product quality. cGMP includes guidance on obtaining quality ingredients, operating procedures, and quality controls.23 Failure to follow cGMP results in possible product contamination.

While the FDA may not have the authority to approve dietary supplements before the product marketing and distribution, it can monitor products via post-marketing surveillance and auditing. The FDA routinely performs manufacturer inspections, monitors the marketplace, and investigates adverse event reports. Follow-up includes working with the manufacturer to bring the product into compliance, issuing warning letters, and recalling products.21

Reporting Issues with Dietary Supplements

Post-marketing surveillance is essential for documenting and monitoring any issues with dietary supplements. Information about severe reactions and product quality are important issues to report. The FDA Safety Reporting Portal is an online tool used to report safety issues on several categories of products, including pet or livestock foods, tobacco products, animal drugs, and dietary supplements.24

The website address for the portal is https://safetyreporting.hhs.gov. Anyone can use the portal to report issues, including consumers, healthcare professionals, manufacturers, and researchers. Generating a new report starts on the home screen. The reporter chooses to file the report as a guest or by creating an account. Creating an account streamlines data entry and allows the reporting individual to save a draft of the report, follow up on a report, and view previous submissions.24

Generation of an Individual Case Safety Report ID (ICSR) occurs after report submission. The ICSR allows the reporter to identify the report for future reference including submission of a follow-up report with additional information. FDA reviewers assess the seriousness of the reported issue and assign follow-up. Submission of this information allows the FDA to identify potentially dangerous products and potentially remove them from the market.24

Traditionally, insurance companies limit coverage to prescription medications. Recent trends show an expansion of coverage to include some dietary supplements. Insurance coverage of dietary supplements blurs the regulatory differences between prescription medications and dietary supplements. Understanding the differences in oversight is beneficial and allows the pharmacy staff to counsel patients effectively.

Situation: While running back to the pharmacy after a much-needed bathroom break, a pharmacist stops when approached by a customer asking for advice about an iron supplement. Overhearing the inquiry, another customer comments, "You should buy that online; it’s cheaper, and the quality is just as good." The pharmacist nods assent, turns, and hurries back to the pharmacy amid the erupting sounds of chaos behind the counter.

Secret #3: Product integrity fluctuates between manufacturers and sources of dietary supplements.

Integrity of Dietary Supplements

The lack of government oversight opens the door for substandard products to flood the market. Poor ingredient quality, heavy metal or microbial contamination, adulteration, and mislabeling occur regularly. In the current economy, with rising prices, consumers are turning to less expensive options, and cheaper is not necessarily better, especially with dietary supplements.

In the literature, many studies exist that analyze dietary supplement product integrity. A study published in 2021 tested multiple bottles of 29 herbal supplements for consistency of ingredient activity and the presence of metal and fungal contaminants. The analysis showed inconsistent ingredient activity not only between bottles of the same product manufactured by the same company, but also between bottles manufactured by different companies. Assaying for metal contamination found zinc in 88% of bottles and nickel in 40% of bottles. In 37 of 58 bottles tested, fungal contamination was present, with 21 bottles having multiple strains.25

Another study analyzed 41 dietary supplements for the presence of cadmium, lead, and mercury. Results revealed that 68.3% of samples contained contamination with cadmium and lead, and 29.3% with mercury.26 One research team evaluated 121 dietary supplements along with 49 prescription drugs for levels of toxic element contamination. A small percentage of the dietary supplement products exceeded safety levels for mercury, lead, cadmium, arsenic, or aluminum. None of the prescription products exceeded these safety levels.27

Adulterated products contain substances not listed on the product labeling, substitution of inferior materials for active ingredients, or may contain a lesser amount of ingredients. Weight loss, sports enhancement, and sexual function supplements commonly contain banned substances.28

The FDA created and currently maintains the Health Fraud Product Database to increase awareness. This database contains information about products cited in warning letters, advisory letters, recalls, public notifications, and press announcements for various issues. Issues cited include products claiming to cure, treat, or prevent a disease and products containing undeclared ingredients or a new dietary ingredient.29 The database is available in the consumer section of the FDA website at https://www.fda.gov/consumers/health-fraud-scams/health-fraud-product-database.

On January 2, 2022, the FDA issued a warning letter to the manufacturers of Nasitrol, a nasal spray based on the ingredient iota carrageenan. A review of the product’s website found claims that the product is intended to mitigate, prevent, treat, diagnose, or cure COVID-19 in people. Federal regulations define products making these claims as drugs and subject to review by the FDA before approval and subsequent marketing. As discussed earlier, this is in direct violation of federal regulations.30

In another example, on July 15, 2022, the FDA issued a public notice advising consumers to refrain from purchasing Adam’s Secret Extra Strength Amazing Black, a product promoted for sexual enhancement. Laboratory analysis found that the product contained tadalafil, a prescription medication used for erectile dysfunction.31 Due to the potential for severe side effects such as hypotension, tadalafil administration requires medical supervision by a physician.32

A study published in 2018 analyzed FDA warning letters issued from 2007 through 2016, using data from the Health Fraud Product Database. During this time frame, the FDA found 776 adulterated dietary supplements from 146 different companies. A total of 157 products contained more than one unapproved ingredient. Products marketed for sexual enhancement accounted for 45.5% of letters, weight loss 40.9%, and muscle building 11.9%. Unapproved ingredients included sildenafil in sexual enhancement, sibutramine in weight loss, and synthetic steroids or steroid-like ingredients in muscle building supplements.33

One way for consumers to know they are purchasing a valid product is by looking for a certified product. The certification process involves an independent, third-party company testing a company’s products, offering quality assurance for dietary supplements. Parameters tested include34

- Product contains the ingredients stated on the label

- Presence of harmful ingredients

- Presence of contamination

- Proper dissolution

- cGMP followed during manufacture

Three independent, private, third-party certifying organizations operate in the United States: the US Pharmacopeial Convention (USP), NSF International, and Consumerlabs.com. All three companies offer product certification programs for a fee. Each company allows products passing certification to display a seal on product labeling. Table 3 summarizes information about each organization.

Table 3. Dietary Supplement Certification Organizations

| Certifying Organization | US Pharmacopeial Convention | NSF International | Consumerlab.com |

| Website | www.usp.org

|

www.nsf.org | www.consumerlab.com |

| Services offered | Dietary supplement verification program including GMP facility audits, product QCM process evaluation, and product testing | Product and ingredient certification

GMP Certification Certified for Sport |

Product reviews

Quality Certification Program |

| Information available on the website | Program information, list of verified products, and educational resources | Program information, product search engine, and educational resources | Product reviews, health condition information |

| GMP = Good Manufacturing Practice | |||

Source: adapted from reference 33

Online product ordering is a convenient shopping option rapidly gaining popularity in recent years, especially during the pandemic. While tempting to order the least expensive product, investigating the source and quality of dietary supplements available online is essential. Proactive training of the entire pharmacy team aids in providing patients with accurate information.

Situation: A weary technician finally finishes ringing out the last customer after two hours straight at the register. A sigh of relief quickly turns into a disgruntled groan as another customer approaches. With a bottle labeled ‘Menopausal Support’ in hand, the customer points to the bottle label and asks, "What does ‘proprietary blend’ mean?" The technician glances over her shoulder, sees the pharmacist engaged in an intense phone conversation, and replies to the customer, "The bottle label clearly lists the ingredients."

Secret #4: Federal regulations define required dietary supplement label information. Unfortunately, ambiguity still exists, making it challenging to identify exactly what the product contains.

Federal regulations define the information required on dietary supplement product labeling in detailed, specific terms. Product labeling must include35

- Product name

- The term ‘dietary supplement’ or similar term (i.e., herbal supplement)

- Name and location of the manufacturer, along with a domestic address and phone number for reporting serious adverse events

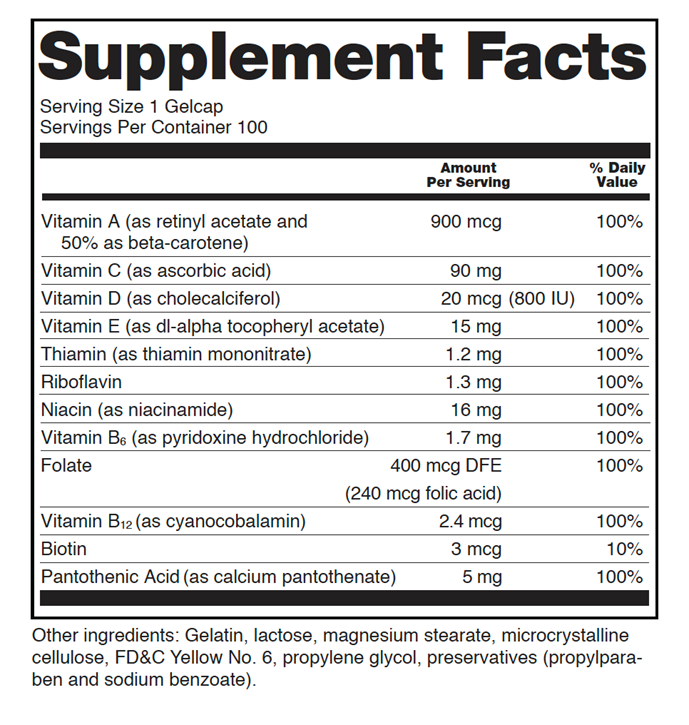

- Nutrition labeling in the form of a “Supplement Facts” panel with the following information (see Figure 1):

- Serving size

- Number of servings per container

- Listing of each dietary ingredient in the product

- Amount of dietary ingredient per serving (Exception: ingredients in a proprietary blend)

- Amount per serving listed as a quantitative amount by weight, as a percentage of the Daily Value, or as both

- A list of other ingredients not declared on the Supplement Facts label (usually excipients such as preservatives or dyes)

- Net quantity of contents

Figure 1. Supplemental Facts Label (sourced from reference 36)

One area of ambiguity in dietary supplement product labeling is the listing of a proprietary blend. The term proprietary blend refers to a blend of dietary ingredients unique to a manufacturer and product. Federal labeling regulations allow the listing of proprietary blends on dietary supplement products, however, only the total weight of the blend is required, not the weight of individual ingredients.35 There is no way for the healthcare professional or consumer to know exactly how much of a particular ingredient the proprietary blend contains.

Consumerlabs.com cautions consumers about products containing proprietary blends or formulas. In many instances, the blend's name sounds like a desired, expensive ingredient that is only a small part of the formula. Marketing of products containing proprietary blends may mislead the consumer with claims meant to impress the consumer and drive sales of the product.37

FDA regulations do allow structure/function claims on dietary supplement labeling. Structure/function claims describe how a nutrient or dietary ingredient may affect or act to maintain the structure or function of the body.35 Examples of structure/function claims include35

- Calcium builds strong bones

- Antioxidants maintain cell integrity

- Fiber maintains bowel integrity

If a dietary supplement label contains a structure/function claim it must also contain the following statement: "This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease."35

The example in this situation involved a product marketed for menopausal support. Menopausal symptoms affect more than 1 million women in the US annually and include symptoms such as hot flashes and sleep disturbances.38 A search of the DSLD using the term ‘menopausal support’ and filtering for on-market products containing the ingredient ‘proprietary blend’ returned almost 3,000 products.9 This abundance of products illustrates the ambiguity that exists on dietary supplement labeling.

Pharmacy technicians are often the first line of contact at the pharmacy. Training and development of pharmacy technicians on the facts surrounding dietary supplements empower technicians, allowing them to answer factual questions and provide effective patient education.

Situation: The pharmacy phone constantly rings throughout the day, and today is no exception. The new COVID vaccine is out, and everyone wants to know if the pharmacy has it in stock. Answering yet another call, the technician is surprised when a patient asks to talk to the pharmacist, complaining about dizziness. The pharmacist checks the patient’s profile, finding no underlying causative medication. Further questioning the patient, the pharmacist uncovers the recent addition of melatonin at night for sleep.

Secret #5: Like prescription medications, dietary supplements have pharmacologic and physiologic effects on the body, potentially resulting in health risks and side effects.

Consumers perceive dietary supplements as safe due to their source from natural substances. While generally well tolerated, dietary supplements affect the body like prescription medications, capable of producing an undesired effect. Lack of regulatory oversight allows products to reach consumers without adequate safety evaluation.

Information describing adverse effects of dietary supplements is anecdotal, derived from case reports and reports submitted through the FDA Safety Reporting Portal. Most dietary supplements have not been studied in pregnant or lactating women or children.

A study published in 2015 evaluated ten years of emergency room data to assess the number of annual visits resulting from dietary supplement adverse events. The authors calculated an average of more than 23,000 emergency room visits stemmed from the consumption of dietary supplements, resulting in more than 2,000 hospitalizations annually.39

Events in older adults accounted for the highest percentage of visits, with 40% of visits due to difficulty swallowing. Incidence in young adults aged 20 to 34 was significant at 28% and primarily involved weight loss and energy products. Side effects reported include heart palpitations, chest pain, and tachycardia.39

Unsupervised child ingestions accounted for 21% of visits. Unlike prescription medications, regulations do not require child-resistant packaging for dietary supplements, except for iron-containing products.39 The authors note the numbers evaluated in the study are likely underreported as patients do not always include dietary supplements with the current medication list.39

Table 4. Adverse Effects of Common Dietary Supplements7,17

| Supplement | Adverse Effects |

| Black Cohosh

|

Breast tenderness, diarrhea, gastrointestinal upset, nausea/vomiting |

| Calcium

|

Burping, constipation, gastrointestinal upset |

| Echinacea

|

Diarrhea, constipation, gastrointestinal upset/pain, heartburn, nausea/vomiting, skin rashes |

| Ginseng | Gastrointestinal side effects, headache, sleep difficulty |

| Ginger

|

Burping, diarrhea, heartburn |

| Iron

|

Abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting |

| Magnesium

|

Diarrhea, gastrointestinal irritation, nausea/vomiting |

| Melatonin

|

Dizziness, drowsiness, headache |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | Bad breath, headache, heartburn, nausea, diarrhea, unpleasant taste |

| Potassium

|

Abdominal pain, burping, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting |

| St. John’s Wort

|

Diarrhea, dizziness, dry mouth, fatigue, headache, insomnia |

| Turmeric

|

Constipation, dyspepsia, gastrointestinal reflux, nausea/vomiting |

| Vitamin C

|

Abdominal cramping, heartburn, kidney stones (if history of kidney stones) |

| Zinc

|

Abdominal cramping, diarrhea, metallic taste, nausea/vomiting |

Patients often fail to report usage of dietary supplements and most pharmacy software lacks the ability to note dietary supplement usage in the patient profile. In this situation, the pharmacist took the extra time to further question the patient about dietary supplement usage and successfully identified the causative agent.

Pause and Ponder: In what ways could you incorporate activities into the daily workflow to increase awareness of patients’ use of dietary supplements?

Situation: Today, the workload in the pharmacy is lighter than usual. With a grateful sigh, the pharmacist sinks onto a stool reaching for a quick snack. Then the phone rings… The caller is a triage nurse from the local hospital to verify a patient’s medication profile. Pulling up the profile, the pharmacist verifies the list of medications, including digoxin. The triage nurse confirms atrial fibrillation as the cause for admission, adding that the patient recently started taking St. John’s Wort for depression.

Secret #6: Some dietary supplements affect the CYP450 liver enzymes, potentially altering the pharmacokinetics of medications, leading to treatment failure and/or toxicity.

Dietary supplement-drug interactions

Drug-drug interactions result in altered absorption, metabolism, or excretion. Drug-dietary supplement interactions occur through the same pathways as those used by FDA-approved drugs. The cytochrome P450 (CYP P450) enzymes in the liver are responsible for the metabolism of most medications.41,42 The ability of a drug to either induce or inhibit these enzymes is a significant factor in drug-drug interactions. The natural ingredients found in dietary supplements are capable of inhibition or induction, also having the potential to interact with medications.

St. John’s Wort, an herbal commonly taken for the relief of mild to moderate depression, induces the activity of CYP3A4.43,44 This induction increases the clearance of medications metabolized by CYP3A4. Examples of medications cleared by CYP3A4 include alprazolam, atorvastatin, cyclosporine, oral contraceptives, oxycodone, and warfarin.43,44 Patients need counseling about potential drug interactions with St. John’s Wort.

Limited clinical studies evaluating the impact of drug-dietary supplement interactions exist. Many interactions are theoretical, based on limited clinical evidence, animal research, and case reports.7

Table 5. Examples of Potential Drug-Dietary Supplement Interactions7,17

| Dietary Supplement | Medication | Interaction |

| Calcium

|

Quinolone and tetracycline antibiotics | Decreased antibiotic efficacy

Take antibiotic 2 hours before or 4-6 hours after calcium |

| Dolutegravir

Elvitegravir |

Reduced serum levels

Take medication 2 hours before or 2 hours after calcium |

|

| Ginseng | Diabetes medications | Increase risk of hypoglycemia |

| Immunosuppressants | Decreased effectiveness of immunosuppressant | |

| Ginkgo

|

Anticoagulants | Increased risk of bleeding |

| Iron

|

Quinolone and tetracycline antibiotics | Decreased levels of antibiotics due to decreased absorption

Take antibiotics 2 hours before or 4-6 hours after iron |

| Magnesium

|

Bisphosphonates | Decreased absorption

|

| Levodopa/carbidopa | Decreased bioavailability of levodopa/carbidopa | |

| Niacin

|

Statins | Increased risk of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis |

| Thyroid hormones | Antagonize the effects of thyroid hormone replacement | |

| Antihypertensive medications | Increased risk of hypotension due to niacin’s vasodilating effects | |

| St. John’s Wort | Alprazolam | Decreased effects of alprazolam |

| Oral Contraceptives | Decreased efficacy

Counsel patients to use other forms of contraception |

|

| Digoxin | Decreased levels of digoxin | |

| Omeprazole | Decreased effects of omeprazole | |

| Valerian | CNS depressant drugs | Additive sedative effects |

| Vitamin B6

|

Phenytoin | Decrease levels and clinical effects of phenytoin |

| Vitamin D

|

Atorvastatin | Decreased absorption of atorvastatin |

| Vitamin E

|

Anticoagulants | Increased risk of bleeding |

| Zinc

|

Quinolone antibiotics | Decreased levels and effects of antibiotics

Take antibiotic 2 hours prior or 4-6 hours after zinc |

Pharmacy training emphasizes the importance of drug-drug interactions. It is important to remember that any substance introduced to the body, including food, beverages, and dietary supplements, has the potential to interact with medications.

Situation: It is another busy day in the pharmacy; prescriptions cover the bench, the phone rings constantly, and a pickup queue extends around the corner. A technician nervously approaches the pharmacist about a patient at the counter with a question regarding a supplement. The pharmacist throws down the spatula, muttering angrily about lacking the knowledge and training to answer the question properly. Sighing, he says, "I’ll just Google it."

Secret #7: Many websites provide clinically backed information on dietary supplements (and Google is not one of them!).

The vast amount of health information available via the Internet with just a few clicks of the keyboard is both a blessing and a curse. Google is now a verb, and a simple search returns millions of results in seconds. While this may seem like a blessing, the curse lies in the searcher's inability to recognize valid, accurate sources of information. In many searches, ads appear as search results adding to the confusion.

In addition to the Internet, consumers turn to social media for health information. Social media use increased from 27% in 2009 to 86% in 2019.45 Information posted on social media provides communication about healthcare issues, potentially resulting in improved health care.45 Unfortunately, inaccurate information abounds on the Internet and social media platforms, leading to consumer misinformation.47-49

The FDA recently launched a new dietary supplement education initiative geared towards consumers, healthcare professionals, and teachers. The program, Supplement Your Knowledge, presents information about dietary supplements through a series of three videos. Educational materials, including fact sheets and infographics, are available in English and Spanish.50

Many government agencies provide free access to information about dietary supplements and their side effects, toxicity, and drug interactions. There are also several paid subscription resources available. Table 6 lists many of the available information options.

Table 6. Sources of Information about Dietary Supplements

| Resource | Website | Information |

| Dietary Supplement Education Program | https://www.fda.gov/food/healthcare-professionals/dietary-supplement-continuing-medical-education-program

|

|

| Dietary Supplement Label Database | https://dsld.od.nih.gov

|

|

| Food and Drug Administration | https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements/information-consumers-using-dietary-supplements

|

|

| Google Scholar

|

https://scholar.google.com/

|

|

| Lexi-Comp

Natural Products Database |

Available via mobile app |

|

| Memorial Sloane Kettering Cancer Center | https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/diagnosis-treatment/symptom-management/integrative-medicine/herbs

|

|

| National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine | https://cam.cancer.gov

|

|

| National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health | https://www.nccih.nih.gov

|

|

| National Library of Medicine - Medline Plus | https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/herb_All.html

|

|

| Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database | https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com

|

|

| Office of Dietary Supplements | https://ods.od.nih.gov |

|

| PubMed | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

|

|

| United States Department of Agriculture | https://www.nutrition.gov/topics/dietary-supplements

|

|

Performing an Internet search via Google may seem like the quickest and easiest way to find the answer to an inquiry. Engaging with the patient, gaining additional information, and knowing where to look ultimately saves time. It is not necessary for one to be an expert in all dietary supplements, just to self-educate one supplement at a time.

Pause and Ponder: A patient shares the unfortunate news about a recent cancer diagnosis. He asks you about the use of herbs in the treatment of cancer. What advice would you give?

Conclusion

You may have noticed a recurring theme throughout this activity. Education. Dietary supplement education is essential to patient safety given the current usage patterns and accessibility of the retail pharmacy team. Education needs to include the entire pharmacy team. Technicians are often the first point of contact at the pharmacy, commonly fielding patient questions. Knowing when to answer questions and when to involve the pharmacist is a necessary skill. Understanding the differences in oversight, the physiological effects of dietary supplement consumption, and the potential for drug interactions allows effective management and counseling of patients. It is important for healthcare providers to solicit information regarding patient consumption of dietary supplements.

Sidebar: Tips for Counseling Patients about Dietary Supplements

Carefully inspect the product to ensure intact product labeling

Ensure the safety seal is intact

Check for an expiration date or best used by date

Check for customer service or return information before ordering

Buy direct from a reputable company; many reputable companies sell through Amazon, avoid 3rd party resellers

Check for the presence of a third-party certification seal

Before purchase, check the company’s website for information on quality standards

Pay attention to the appearance and smell of the product upon opening

Child-resistant packaging is not a requirement for dietary supplements; advise on proper storage of product

Reinforce the importance of including dietary supplements on a current medication list

Pharmacist Post Test (for viewing only)

Seven Secrets for Patient Safety with Dietary Supplements

Pharmacist post-test

After completing this continuing education activity, pharmacists will be able to:

1. Discuss the importance of knowing about a patient’s dietary supplement usage (K)

2. Identify commonly used dietary supplements, their regulation, and the value of certification (K, or A?)

3. Recognize potential medication-dietary supplement interactions (K)

4. Demonstrate the ability to locate different sources of information about dietary supplements (A)

1. According to The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey more than what percentage of adults have used a dietary supplement in the last 30 days?

A. 45%

B. 50%

C. 55%

2. Which of the following is a commonly used dietary supplement?

A. Boswellia

B. Turmeric

C. Quercetin

3. Which government agencies regulate dietary supplements?

A. USDA, FDA

B. FTC, DEA

C. FTC, FDA

4. Patient MW fills a new prescription for bumetanide. Which potential nutrient depletion may occur?

A. Magnesium

B. Vitamin D

C. Vitamin B12

5. While completing an inventory reconciliation of the vitamin section, a technician inquires, ‘Why does the FDA approve so many different products?’ Which of the following is the most appropriate answer?

A. ‘The FDA does not have the authority to approve dietary supplements, the FTC approves dietary supplements, including vitamins.’

B. ‘The FDA does not have the authority to approve dietary supplements before they are marketed, allowing manufacturers to flood the market with products.’

C. ‘You know, I’m not sure, probably just to make it more confusing for us.’

6. Which of the following companies offer independent third-party dietary supplement certification services?

A. Consumer Reports

B. NSF International

C. Certified Naturally Grown

7. Patient ED is a 58-year-old male new to your pharmacy. He provides the pharmacy team with a list of his current medications including:

• Warfarin 3 mg PO QD

• Atorvastatin 10 mg PO QD

• Donepezil 10 mg PO QHS

• Metformin 1,000 mg PO BID

Use of which of the following supplements would be cause for concern in this patient?

A. Ginkgo

B. Omega-3 fatty acids

C. Niacin

8. A patient calls with questions about a supplement recommended by a friend. The name of the supplement is Mind and Memory Essentials, and the patient does not know the product ingredients. Where would you go to find this information?

A. Dietary Supplement Label Database

B. Office of Dietary Supplements

C. United States Department of Agriculture

9. A patient asks you about the potential side effects of taking turmeric. Where would you go to find this information?

A. Google

B. PubMed

C. Office of Dietary Supplements

10. You are verifying a new birth control prescription for a patient, recalling that the patient strongly believes in alternative medicine and dietary supplementation. Thankfully her profile contains a list of dietary supplements. You see St. John’s Wort listed and suspect a drug-supplement interaction. Where would you go to find more information?

A. Natural Medicines Database

B. Google Scholar

C. National Library of Medicine

11. One of your regular patients stops by the counter to ask your opinion on a dietary supplement product purchased on the Internet. What should you assess when looking over the product?

A. Product labeling, color of bottle, structure/function disclaimer, certification

B. Certification, expiration date, product labeling, intact seal

C. Expiration date, product price, certification, product labeling

12. Pharmacy patient ML approaches the pharmacy counter to purchase several bottles of oral glucose tablets. When questioned, the patient reveals the recent occurrence of several hypoglycemic episodes. The patient confirms compliance with taking their prescription for metformin 1 gm PO BID. ML reports no changes in other prescriptions or dietary habits but does state they started taking a dietary supplement a few days ago but cannot recall the name. Which product would you suspect based on the information provided?

A. Vitamin E

B. Valerian

C. Ginseng

Pharmacy Technician Post Test (for viewing only)

Pharmacy Technician

After completing this continuing education activity, pharmacy technicians will be able to:

1. Discuss the importance of knowing about a patient’s dietary supplement usage (K)

2. Identify commonly used dietary supplements (A)

3. Define dietary supplement oversight and different levels of quality (K)

4. Recognize the need for pharmacist counseling when a patient is taking a dietary supplement (K)

1. Why is it important to ask about a patient’s usage of dietary supplements?

A. It is not important to ask about dietary supplement usage.

B. To identify which dietary supplements the pharmacy should feature on the front counter.

C. Dietary supplements potentially interact with prescription medications.

2. Which of the following is a commonly used dietary supplement?

A. Boswellia

B. Turmeric

C. Quercetin

3. Which government agencies regulate dietary supplements?

A. USDA, FDA

B. FTC, DEA

C. FTC, FDA

4. A patient approaches the counter with 2 different magnesium products and asks your opinion on which to purchase. Which of the following is an appropriate answer?

A. Let’s look at these a little closer.

B. Neither, it’s better to buy supplements online.

C. The one that’s on sale.

5. Reasons for dietary supplementation include which of the following?

A. To supplement a poor diet.

B. Promotion of optimal immune health

C. No one needs to take dietary supplements.

6. Which of the following companies offer independent third-party dietary supplement certification services?

A. Consumer Reports

B. NSF International

C. Certified Naturally Grown

7. You are entering a new patient into the pharmacy system. In addition to asking about allergies, demographics, and current medications, what else should you ask?

A. How many hours of sleep do you average a night?

B. Do you take any over-the-counter medications or dietary supplements?

C. How many children do you have and how old are they?

8. You are finally heading out for a lunch break and walk past a pharmacy patient in the aisle looking at 2 different brands of St. John’s Wort. What should you do?

A. Keep going, you already punched out and only have 30 min to eat your lunch.

B. Stop and offer to accompany them to the pharmacy to talk to the pharmacist.

C. Stop and help them make a choice between the products.

9. A patient picks up a medication and purchases a bottle of magnesium at the same time. What should you do?

A. Advise the patient that there may be an interaction between the prescription and the magnesium.

B. Ring out the patient as usual.

C. Touch base with the pharmacist to make sure there are no potential interactions between the products.

10. Where should adverse reactions or issues with dietary supplements be reported?

A. FDA Safety Reporting Portal

B. Federal Trade Commission

C. Office of Dietary Supplements

References

Full List of References

References

1. Cragg GM, Newman DJ. Natural products: a continuing source of novel drug leads. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(6):3670-3695. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.008

2. Jones AW. Early drug discovery and the rise of pharmaceutical chemistry. Drug Test Anal. 2011;3(6):337-344. doi:10.1002/dta.301

3. Aitken M, Kleinrock M. The Use of Medicines in the U.S. Spending and Usage Trends and Outlook to 2025. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. May 2021. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/the-use-of-medicines-in-the-us/iqi-the-use-of-medicines-in-the-us-05-21-forweb.pdf

4. OTC Sales Statistics. Consumer Healthcare Products Association. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.chpa.org/about-consumer-healthcare/research-data/otc-sales-statistics

5. Dietary Supplements Market Size, Share & COVID-19 Impact Analysis, By Type (Vitamins, Minerals, Enzymes, Fatty Acids, Proteins, and Others), Form (Tablets, Capsules, Liquids, and Powders), and Regional Forecasts, 2021-2028. Fortune Business Insights. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/dietary-supplements-market-102082

6. Moynihan R, Sanders S, Michaleff ZA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare services: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e045343. Published 2021 Mar 16. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343

7. Dietary Supplements in the Time of COVID-19. Fact Sheet for Health Professionals. National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/COVID19-HealthProfessional/.

8. Adams KK, Baker WL, Sobieraj DM. Myth Busters: Dietary Supplements and COVID-19. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54(8):820-826. doi:10.1177/1060028020928052

9. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary Supplement Label Database (DSLD). Accessed August 5, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/Research/Dietary_Supplement_Label_Database.aspx

10. About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. National Center for Health Statistics. Accessed July 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

11. Mishra S, Stierman B, Gahche JJ, Potischman N. Dietary supplement use among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 399. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:101131external icon

12. Gahche JJ, Bailey RL, Potischman N, et al. Federal Monitoring of Dietary Supplement Use in the Resident, Civilian, Noninstitutionalized US Population, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Nutr. 2018;148(Suppl 2):1436S-1444S. doi:10.1093/jn/nxy093

13. 2019 CRN Consumer Survey on Dietary Supplements. Council for Responsible Nutrition. https://www.crnusa.org/2019survey. Published September 30, 2019. Accessed June 1, 2022.

14. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/. Accessed August 5, 2022.

15. Calder PC, Carr AC, Gombart AF, Eggersdorfer M. Optimal Nutritional Status for a Well-Functioning Immune System Is an Important Factor to Protect against Viral Infections. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):1181. Published 2020 Apr 23. doi:10.3390/nu12041181

16. Hamulka J, Jeruszka-Bielak M, Górnicka M, Drywień ME, Zielinska-Pukos MA. Dietary Supplements during COVID-19 Outbreak. Results of Google Trends Analysis Supported by PLifeCOVID-19 Online Studies. Nutrients. 2020;13(1):54. Published 2020 Dec 27. doi:10.3390/nu13010054

17. Natural Medicines. Therapeutic Research Center. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com.

18. Office of Dietary Supplements Dietary Supplement Fact Sheets. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all/

19. U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. Available at DietaryGuidelines.gov. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf

20. Thakkar S, Anklam E, Xu A, et al. Regulatory landscape of dietary supplements and herbal medicines from a global perspective. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2020;114:104647. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2020.104647

21. FDA 101: Dietary supplements. United States Food and Drug Administration. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/fda-101-dietary-supplements.

22. Questions and Answers on Dietary Supplements. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/information-consumers-using-dietary-supplements/questions-and-answers-dietary-supplements.

23. Facts About the Current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed July 22, 2022.

https://www.fda.gov/drugs/pharmaceutical-quality-resources/facts-about-current-good-manufacturing-practices-cgmps

24. Safety Reporting Portal. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www.safetyreporting.hhs.gov/SRP2/en/Home.aspx?sid=da6dc761-7962-4743-82cd-2e62985492d0

25. Veatch-Blohm ME, Chicas I, Margolis K, Vanderminden R, Gochie M, Lila K. Screening for consistency and contamination within and between bottles of 29 herbal supplements. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0260463. Published 2021 Nov 23. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260463

26. Ćwieląg-Drabek M, Piekut A, Szymala I, et al. Health risks from consumption of medicinal plant dietary supplements. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8(7):3535-3544. Published 2020 May 19. doi:10.1002/fsn3.1636

27. Genuis SJ, Schwalfenberg G, Siy AK, Rodushkin I. Toxic element contamination of natural health products and pharmaceutical preparations. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e49676. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049676

28. Tucker J, Fischer T, Upjohn L, Mazzera D, Kumar M. Unapproved Pharmaceutical Ingredients Included in Dietary Supplements Associated With US Food and Drug Administration Warnings [published correction appears in JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Nov 2;1(7):e185765]. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183337. Published 2018 Oct 5. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3337

29. Health Fraud Product Database. United States Food and Drug Administration. Accessed August 10, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/health-fraud-scams/health-fraud-product-database

30. Warning Letter: Amcyte Pharma, Inc. United States Food and Drug Administration. January 03, 2022. Accessed August 12, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/amcyte-pharma-inc-623474-01032022

31. Public Notification: Adam’s Secret Extra Strength Amazing Black contains hidden drug ingredient. United States Food and Drug Administration. July 15, 2022. Accessed August 12, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/medication-health-fraud/public-notification-adams-secret-extra-strength-amazing-black-contains-hidden-drug-ingredient

32. Coward, RM, Carson CC. Tadalafil in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(6):1315-1329. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2643112/pdf/TCRM-4-1315.pdf

33. Tucker J, Fischer T, Upjohn L, Mazzera D, Kumar M. Unapproved Pharmaceutical Ingredients Included in Dietary Supplements Associated With US Food and Drug Administration Warnings [published correction appears in JAMA Netw Open. 2018 Nov 2;1(7):e185765]. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(6):e183337. Published 2018 Oct 5. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3337

34. Akabas SR, Vannice G, Atwater JB, Cooperman T, Cotter R, Thomas L. Quality Certification Programs for Dietary Supplements. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(9):1370-1379. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2015.11.003

35. Dietary Supplement Labeling Guide, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements-guidance-documents-regulatory-information/dietary-supplement-labeling-guide Accessed July 15, 2022.

36. Frequently Asked Questions for Industry on Nutrition Facts Labeling Requirements. United States Food and Drug Administration. Accessed August 12, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/99158/download

37. Cooperman, T. 6 Red Flags to Watch Out For When Buying Vitamins & Supplements. October 9, 2021. Accessed August 12, 2022. https://www.consumerlab.com/answers/what-to-watch-out-for-when-buying-vitamins-and-supplements/vitamin-and-supplement-red-flags

38. Research explores the impact of menopause on women’s health and aging. National Institute of Aging. May 6, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/research-explores-impact-menopause-womens-health-and-aging

39. Geller AI, Shehab N, Weidle NJ, et al. Emergency Department Visits for Adverse Events Related to Dietary Supplements. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(16):1531-1540. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1504267

40. Code of Federal Regulations. Title 16, Chapter II, Subchapter E, Part 1700. Amended September 6, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-16/chapter-II/subchapter-E/part-1700/section-1700.14

41. Zanger UM, Turpeinen M, Klein K, Schwab M. Functional pharmacogenetics/genomics of human cytochromes P450 involved in drug biotransformation. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;392(6):1093-1108. doi:10.1007/s00216-008-2291-6

42. Matura JM, Shea LA, Bankes VA. Dietary supplements, cytochrome metabolism, and pharmacogenetic considerations [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 4]. Ir J Med Sci. 2021;10.1007/s11845-021-02828-4. doi:10.1007/s11845-021-02828-4

43. Chrubasik-Hausmann S, Vlachojannis J, McLachlan AJ. Understanding drug interactions with St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum L.): impact of hyperforin content. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2019;71(1):129-138. doi:10.1111/jphp.12858

44. Zhou S, Chan E, Pan SQ, Huang M, Lee EJ. Pharmacokinetic interactions of drugs with St John's wort. J Psychopharmacol. 2004;18(2):262-276. doi:10.1177/0269881104042632

45. Chen J, Wang Y. Social Media Use for Health Purposes: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(5):e17917. Published 2021 May 12. doi:10.2196/17917

46. Moorhead SA, Hazlett DE, Harrison L, Carroll JK, Irwin A, Hoving C. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(4):e85. Published 2013 Apr 23. doi:10.2196/jmir.1933

47. Swire-Thompson B, Lazer D. Public Health and Online Misinformation: Challenges and Recommendations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:433-451. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094127

48. Chou WS, Oh A, Klein WMP. Addressing Health-Related Misinformation on Social Media. JAMA. 2018;320(23):2417-2418. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.16865

49. Suarez-Lledo V, Alvarez-Galvez J. Prevalence of Health Misinformation on Social Media: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(1):e17187. Published 2021 Jan 20. doi:10.2196/17187

50. Supplement Your Knowledge. Dietary Supplement Education Initiative. United States Food and Drug Administration. May 25, 2022. Accessed July 20, 2022. Reference the Supplement your knowledge program